NIH Public Access Author Manuscript J Hepatol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Molecular and Physiological Basis for Hair Loss in Near Naked Hairless and Oak Ridge Rhino-Like Mouse Models: Tracking the Role of the Hairless Gene

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2006 Molecular and Physiological Basis for Hair Loss in Near Naked Hairless and Oak Ridge Rhino-like Mouse Models: Tracking the Role of the Hairless Gene Yutao Liu University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Life Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Liu, Yutao, "Molecular and Physiological Basis for Hair Loss in Near Naked Hairless and Oak Ridge Rhino- like Mouse Models: Tracking the Role of the Hairless Gene. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2006. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/1824 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Yutao Liu entitled "Molecular and Physiological Basis for Hair Loss in Near Naked Hairless and Oak Ridge Rhino-like Mouse Models: Tracking the Role of the Hairless Gene." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Life Sciences. Brynn H. Voy, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Naima Moustaid-Moussa, Yisong Wang, Rogert Hettich Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. -

Bioinformatics Analyses of Genomic Imprinting

Bioinformatics Analyses of Genomic Imprinting Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades des Doktors der Naturwissenschaften der Naturwissenschaftlich-Technischen Fakultät III Chemie, Pharmazie, Bio- und Werkstoffwissenschaften der Universität des Saarlandes von Barbara Hutter Saarbrücken 2009 Tag des Kolloquiums: 08.12.2009 Dekan: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Stefan Diebels Berichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Volkhard Helms Priv.-Doz. Dr. Martina Paulsen Vorsitz: Prof. Dr. Jörn Walter Akad. Mitarbeiter: Dr. Tihamér Geyer Table of contents Summary________________________________________________________________ I Zusammenfassung ________________________________________________________ I Acknowledgements _______________________________________________________II Abbreviations ___________________________________________________________ III Chapter 1 – Introduction __________________________________________________ 1 1.1 Important terms and concepts related to genomic imprinting __________________________ 2 1.2 CpG islands as regulatory elements ______________________________________________ 3 1.3 Differentially methylated regions and imprinting clusters_____________________________ 6 1.4 Reading the imprint __________________________________________________________ 8 1.5 Chromatin marks at imprinted regions___________________________________________ 10 1.6 Roles of repetitive elements ___________________________________________________ 12 1.7 Functional implications of imprinted genes _______________________________________ 14 1.8 Evolution and parental conflict ________________________________________________ -

Organizing Knowledge to Enable Faster Data Interpretation in COVID

F1000Research 2021, 10(ELIXIR):703 Last updated: 01 SEP 2021 DATA NOTE Organizing knowledge to enable faster data interpretation in COVID-19 research [version 1; peer review: 2 approved with reservations] Joseph Hearnshaw, Marco Brandizi, Ajit Singh , Chris Rawlings , Keywan Hassani-Pak Rothamsted Research, Harpenden, AL5 2JQ, UK v1 First published: 30 Jul 2021, 10(ELIXIR):703 Open Peer Review https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.54071.1 Latest published: 30 Jul 2021, 10(ELIXIR):703 https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.54071.1 Reviewer Status Invited Reviewers Abstract Enormous volumes of COVID-19 research data have been published 1 2 and this continues to increase daily. This creates challenges for researchers to interpret, prioritize and summarize their own findings version 1 in the context of published literature, clinical trials, and a multitude of 30 Jul 2021 report report databases. Overcoming the data interpretation bottleneck is vital to help researchers to be more efficient in their quest to identify COVID- 1. Justin Reese , Lawrence Berkeley National 19 risk factors, potential treatments, drug side-effects, and much more. As a proof of concept, we have organized and integrated a Laboratory, Berkeley, USA range of COVID-19 and human biomedical data and literature into a knowledge graph (KG). Here we present the datasets we have 2. Keith Hall , Google Research, New York, integrated so far and the content of the KG which consists of 674,969 USA biological concepts and over 1.6 million relationships between them. The COVID-19 KG is available via KnetMiner, an interactive online Any reports and responses or comments on the platform for gene discovery and knowledge mining, or via RDF and article can be found at the end of the article. -

LJELSR: a Strengthened Version of JELSR for Feature Selection and Clustering

Article LJELSR: A Strengthened Version of JELSR for Feature Selection and Clustering Sha-Sha Wu 1, Mi-Xiao Hou 1, Chun-Mei Feng 1,2 and Jin-Xing Liu 1,* 1 School of Information Science and Engineering, Qufu Normal University, Rizhao 276826, China; [email protected] (S.-S.W.); [email protected] (M.-X.H.); [email protected] (C.-M.F.) 2 Bio-Computing Research Center, Harbin Institute of Technology, Shenzhen 518055, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +086-633-3981-241 Received: 4 December 2018; Accepted: 7 February 2019; Published: 18 February 2019 Abstract: Feature selection and sample clustering play an important role in bioinformatics. Traditional feature selection methods separate sparse regression and embedding learning. Later, to effectively identify the significant features of the genomic data, Joint Embedding Learning and Sparse Regression (JELSR) is proposed. However, since there are many redundancy and noise values in genomic data, the sparseness of this method is far from enough. In this paper, we propose a strengthened version of JELSR by adding the L1-norm constraint on the regularization term based on a previous model, and call it LJELSR, to further improve the sparseness of the method. Then, we provide a new iterative algorithm to obtain the convergence solution. The experimental results show that our method achieves a state-of-the-art level both in identifying differentially expressed genes and sample clustering on different genomic data compared to previous methods. Additionally, the selected differentially expressed genes may be of great value in medical research. Keywords: differentially expressed genes; feature selection; L1-norm; sample clustering; sparse constraint 1. -

A Functional and Regulatory Map of Asthma

A Functional and Regulatory Map of Asthma Noa Novershtern1, Zohar Itzhaki2, Ohad Manor3, Nir Friedman1, and Naftali Kaminski4 1School of Computer Science and Engineering, 2Department of Molecular Genetics and Biotechnology, Faculty of Medicine, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem; 3Department of Computer Science and Applied Mathematics, The Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel; and 4Dorothy P. and Richard P. Simmons Center for Interstitial Lung Diseases, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania The prevalence and morbidity of asthma, a chronic inflammatory airway disease, is increasing. Animal models provide a meaningful CLINICAL RELEVANCE but limited view of the mechanisms of asthma in humans. A systems- level view of asthma that integrates multiple levels of molecular and In this article, we provide a framework for a systems-level functional information is needed. For this, we compiled a gene ex- analysisofmicroarraydataandcreateaglobalmapof pression compendium from five publicly available mouse microarray asthma. Our insights, the analytic framework, and the datasets and a gene knowledge base of 4,305 gene annotation sets. accompanying website should be of use to basic and clinical Using this collection we generated a high-level map of the functional asthma researchers. themes that characterize animal models of asthma, dominated by innate and adaptive immune response. We used Module Networks analysis to identify co-regulated gene modules. The resulting mod- and STAT6 during the development of allergen-induced lung ules reflect four distinct responses to treatment, including early inflammation (7–9). Transcriptional analysis of the response to response, general induction, repression, and IL-13–dependent re- IL-13, allergen challenge, syncytial virus infection, and cortico- sponse. -

Inline-Supplementary-Material-6.Pdf

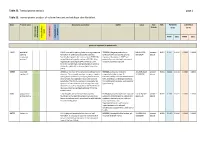

Table S3. Transcriptome analysis page 1 Table S3. Transcriptomic analysis of cultured mutant and wildtype skin fibroblast. Gene Protein name GeneCards annotation OMIM Locus Fold FDR PATIENTS CONTROLS - change (n=2) (n=4) ment apoptosis apoptosis Keratinocyte Keratinocyte inflammation differentiation Neurodevelop cell growth and growth cell FPKM [SD] FPKM [SD] genes up-regulated in patient cells ESRP1 epithelial ESRP1 is an mRNA splicing factor that regulates the *612959, the gene product is an 8:95653301 - present - 0.011 0.3547 0.0038 0.0000 0.0000 splicing formation of epithelial cell-specific isoforms. epithelial cell-type-specific splicing 95719694 absent regulatory Specifically regulates the expression of FGFR2-IIIb, regulator. Mutations in ESRP1 are protein 1 an epithelial cell-specific isoform of FGFR2. Also potentially associated with autosomal regulates the splicing of CD44, CTNND1, ENAH, recessive deafness type 109. three transcripts that undergo changes in splicing during the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). CERS3 ceramide CERS3 is a member of the ceramide synthase family #615023, autosomal recessive 15:100913143 - present - 0.011 0.1844 0.0118 0.0000 0.0000 synthase 3 of genes. The ceramide synthase enzymes regulate congenital ichthyosis type 9, 101085200 absent sphingolipid synthesis by catalyzing the formation characterized by collodian membrane at of ceramides from sphingoid base and acyl-CoA birth, acanthosis, orthohyperkeratosis, substrates. This family member is involved in the fine erythrodermic scales, palmoplantar synthesis of ceramides with ultra-long-chain acyl- hyperlinearity. moieties (ULC-Cers), important to the epidermis in its role in creating a protective barrier from the environment. GJB6 gap junction GJB6 encodes one of the connexin proteins. -

Application No. AU 2008264201 Al (19) AUSTRALIAN PATENT OFFICE

(12) STANDARD PATENT APPLICATION (11) Application No. AU 2008264201 Al (19) AUSTRALIAN PATENT OFFICE (54) Title Modified recombinant vaccinia viruses and other microorganisms, uses thereof (51) International Patent Classification(s) A61K 35/74 (2006.01) C12N 7/04 (2006.01) A61K 35/76 (2006.01) C12N 15/863 (2006.01) A61P 35/00 (2006.01) A61K 39/00 (2006.01) C07K 16/30 (2006.01) A61K 48/00 (2006.01) C07K 16/40 (2006.01) (21) Application No: 2008264201 (22) Date of Filing: 2008.12.24 (43) Publication Date: 2009.01.29 (43) Publication Journal Date: 2009.01.29 (62) Divisional of: 2004289953 (71) Applicant(s) Genelux Corporation (72) Inventor(s) Szalay, Aladar A.;Yu, Yong A.;Zhang, Qian;Timiryasova, Tatyana (74) Agent Attorney Spruson Ferguson, Level 35 St Martins Tower 31 Market Street, Sydney, NSW, 2000 MODIFIED RECOMBINANT VACCINIA VIRUSES AND OTHER 00 MICROORGANISMS, USES THEREOF O SAbstract 0 Recombinant vaccinia viruses useful as tumor-specific delivery vehicle for cancer gene therapy and vaccination Therapeutic methods and microorganisms therefore are provided. The microorganisms are designed to accumulate in immunoprivileged tissues and cells, such as tumors and other proliferating tissue and in inflamed tissues, compared to other O 0 tissues, cells and organs, so that they exhibit relatively low toxicity to host organisme. 0 The microorganisms also are designed or modified to result in leaky cell membranes of Scells in which they accumulate, resulting in production of antibodies reactive against proteins and other cellular products and also permitting exploitation of proliferating tissues, particularly tumors, to produce selected proteins and other products. -

Downloaded from the Mouse Lysosome Gene Database, Mlgdb

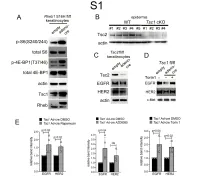

1 Supplemental Figure Legends 2 3 Supplemental Figure S1: Epidermal-specific mTORC1 gain-of-function models show 4 increased mTORC1 activation and down-regulate EGFR and HER2 protein expression in a 5 mTORC1-sensitive manner. (A) Immunoblotting of Rheb1 S16H flox/flox keratinocyte cultures 6 infected with empty or adenoviral cre recombinase for markers of mTORC1 (p-S6, p-4E-BP1) 7 activity. (B) Tsc1 cKO epidermal lysates also show decreased expression of TSC2 by 8 immunoblotting of the same experiment as in Figure 2A. (C) Immunoblotting of Tsc2 flox/flox 9 keratinocyte cultures infected with empty or adenoviral cre recombinase showing decreased EGFR 10 and HER2 protein expression. (D) Expression of EGFR and HER2 was decreased in Tsc1 cre 11 keratinocytes compared to empty controls, and up-regulated in response to Torin1 (1µM, 24 hrs), 12 by immunoblot analyses. Immunoblots are contemporaneous and parallel from the same biological 13 replicate and represent the same experiment as depicted in Figure 7B. (E) Densitometry 14 quantification of representative immunoblot experiments shown in Figures 2E and S1D (r≥3; error 15 bars represent STDEV; p-values by Student’s T-test). 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Supplemental Figure S2: EGFR and HER2 transcription are unchanged with epidermal/ 24 keratinocyte Tsc1 or Rptor loss. Egfr and Her2 mRNA levels in (A) Tsc1 cKO epidermal lysates, 25 (B) Tsc1 cKO keratinocyte lysates and(C) Tsc1 cre keratinocyte lysates are minimally altered 26 compared to their respective controls. (r≥3; error bars represent STDEV; p-values by Student’s T- 27 test). -

Molecular Characterization of a Novel Amplicon at I Q21 -Q22 Frequently Observed in Human Sarcomas

British Joumal of Cancer (1998) 78(4), 495-503 C 1998 Cancer Research Campaign Molecular characterization of a novel amplicon at I q21 -q22 frequently observed in human sarcomas A Forus', J-M Berner1, LA Meza-Zepeda1, G Saeter2, D Mischke3, 0 Fodstad' and 0 Myklebost' Departments of 'Tumour Biology and 2Clinical Oncology, The Norwegian Radium Hospital, 0310 Oslo, Norway; 31nstitut fur Experimentelle Onkologie und Transplantationsmedizin, Virchow-Klinikum, Spandauer Damm 130, D-14050 Berlin, Germany Summary In a recent comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) study of a panel of sarcomas, we detected recurrent amplification of 1q21-q22 in soft tissue and bone tumours. Amplification of this region had not previously been associated with sarcoma development, but occasional amplification of CACY/S100A6 and MUC1 in 1q21 had been reported for melanoma and breast carcinoma respectively. Initial screening by Southern blot analysis showed amplification of S100A6, FLG and SPRR3 in several sarcomas and, in a first attempt to characterize the 1q21-q22 amplicon in more detail, we have now investigated the amplification status of these and 11 other markers in the region in 35 sarcoma samples. FLG was the most frequently amplified gene, and the markers located in the same 4.5-Mb region as FLG showed a higher incidence of amplification than the more distal ones. However, for most of the 14 markers, amplification levels were low, and only APOA2 and the anonymous marker D1S3620 showed high-level amplifications (> tenfold increases) in one sample each. We used fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to determine the amplification patterns of two overlapping yeast artificial chromosomes (YACs) covering the region between Dl S3620 and FLG (789f2 and 764a1), as well as two more distally located YACs in nine selected samples. -

Antioxidant Properties of Small Proline-Rich Proteins : from Epidermal Cornification to Global ROS Detoxification and Wound Healing Vermeij, W.P

Antioxidant properties of small proline-rich proteins : from epidermal cornification to global ROS detoxification and wound healing Vermeij, W.P. Citation Vermeij, W. P. (2011, December 6). Antioxidant properties of small proline-rich proteins : from epidermal cornification to global ROS detoxification and wound healing. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/18185 Version: Corrected Publisher’s Version Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/18185 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Antioxidant properties of small proline-rich proteins from epidermal cornification to global ROS detoxification and wound healing Wilbert Vermeij The research presented in this thesis was performed at the department of Molecular Genetics, Leiden Institute of Chemistry, Leiden University, The Netherlands. Cover: The Matusevich Glacier flowing towards the eastern coast of Antarctica. Image was taken by the Earth Observatory, EO-1 Advanced Land Imager, NASA. ISBN: 978-94-6182-048-8 © Wilbert Vermeij, The Netherlands, 2011. All rights reserved. No part of this thesis may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission from the author. Financial support for the printing of this thesis has been kindly provided by LEO Pharma BV, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Printed by Off Page, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Antioxidant properties of small proline-rich proteins from epidermal cornification to global ROS detoxification and wound healing PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van Rector Magnificus Prof. Mr. P.F. -

(LCK) As a Driver for Invasion and Migration of Oral Cancer B

Weiße et al. Molecular Cancer (2021) 20:88 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-021-01384-w RESEARCH Open Access Identification of lymphocyte cell-specific protein-tyrosine kinase (LCK) as a driver for invasion and migration of oral cancer by tumor heterogeneity exploitation Jonas Weiße1, Julia Rosemann1†, Lisa Müller2†, Matthias Kappler3, Alexander W. Eckert4, Markus Glaß5, Danny Misiak5, Stefan Hüttelmaier5, Wolfgang G. Ballhausen6, Mechthild Hatzfeld2, Monika Haemmerle7 and Tony Gutschner1* Abstract Background: Cancer metastases are the main cause of lethality. The five-year survival rate for patients diagnosed with advanced stage oral cancer is 30%. Hence, the identification of novel therapeutic targets is an urgent need. However, tumors are comprised of a heterogeneous collection of cells with distinct genetic and molecular profiles that can differentially promote metastasis making therapy development a challenging task. Here, we leveraged intratumoral heterogeneity in order to identify drivers of cancer cell motility that might be druggable targets for anti-metastasis therapy. Methods: We used 2D migration and 3D matrigel-based invasion assays to characterize the invasive heterogeneity among and within four human oral cancer cell lines in vitro. Subsequently, we applied mRNA-sequencing to map the transcriptomes of poorly and strongly invasive subclones as well as primary tumors and matched metastasis. Results: We identified SAS cells as a highly invasive oral cancer cell line. Clonal analysis of SAS yielded a panel of 20 subclones with different invasive capacities. Integrative gene expression analysis identified the Lymphocyte cell- specific protein-tyrosine kinase (LCK) as a druggable target gene associated with cancer cell invasion and metastasis. Inhibition of LCK using A-770041 or dasatinib blocked invasion of highly aggressive SAS cells. -

SPRR4, a Novel Cornified Envelope Precursor: UV

RESEARCH ARTICLE 3837 SPRR4, a novel cornified envelope precursor: UV- dependent epidermal expression and selective incorporation into fragile envelopes Adriana Cabral1, Arzu Sayin1, Sandrine de Winter2, David F. Fischer1, Stan Pavel2 and Claude Backendorf1,* 1Department of Molecular Genetics, Leiden Institute of Chemistry, Leiden University, PO Box 9502, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands 2Department of Dermatology, Leiden University Medical Centre, The Netherlands *Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) Accepted 16 July 2001 Journal of Cell Science 114, 3837-3843 (2001) © The Company of Biologists Ltd SUMMARY The cornified cell envelope (CE), a structure formed in translocation of an SPRR4-GFP fusion protein to the cell the outermost layers of stratified squamous epithelia, periphery in living keratinocytes and its integration into provides a physical barrier against environmental both rigid and fragile cornified envelopes proved that insults. It is composed of several structural proteins, SPRR4 is a novel CE precursor. Interestingly, after UV which are irreversibly crosslinked by calcium-activated irradiation, SPRR4 was selectively incorporated into transglutaminases. The small proline rich proteins fragile CEs. Our results show for the first time that UV- (SPRRs) are one set of CE precursors. SPRR4, a novel induced cornification is accompanied by qualitative member of this gene family, displayed very low or changes in CE precursor assembly. SPRR4 is part of an undetectable expression levels in normal human skin or adaptive tissue response to environmental stress, which is other stratified squamous epithelia, but was clearly induced likely to compensate for UV induced impairment of the by UV light both in vivo and in vitro.