Chiefdoms and Chieftancies in Fiji. Yesterday and Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

Introduction Brij V. Lal Soldiers rioting on the steps of parliament house in Papua New Guinea; tumultuous politics besetting the presidency in Vanuatu; political assassi nations in New Caledonia; confrontation between soldiers and civilians on the troubled island of Bougainville. In other, calmer times, such inci dents of terror and violence would have stunned observers of Pacific Island affairs. But in the aftermath of the dramatic events in Fiji, news of upheaval in the islands is increasingly being greeted with a weary sense of deja vu. Such has been their impact that the Fiji coups and the forces they have unleashed are already being seen as marking, for better or worse, a turning point not only in the history ofthat troubled island nation but also in the contemporary politics ofthe Pacific Islands region. The issues and emotions that the Fiji coups have engendered touch on some of the most fundamental issues of our time: the tension between the rights ofindigenous peoples ofthe Pacific Islands and the rights ofthose of more recent immigrant or mixed origins; the role and place of traditional customs and institutions in the fiercely competitive modern political arena; the structure and function of Western-style democratic political processes in ethnically divided or nonegalitarian societies; the use of mili tary force to overthrow ideologically unacceptable but constitutionally elected governments. These and similar issues, rekindled by the events in Fiji, will be with us for a long time to come. Unlike any other event in recent Pacific Islands history, the Fiji crisis has generated an unprecedented outpouring of popular and scholarly litera ture, as our Book Review and Resources sections amply demonstrate. -

A Socio-Cultural Investigation of Indigenous Fijian Women's

A Socio-cultural Investigation of Indigenous Fijian Women’s Perception of and Responses to HIV and AIDS from the Two Selected Tribes in Rural Fiji Tabalesi na Dakua,Ukuwale na Salato Ms Litiana N. Tuilaselase Kuridrani MBA; PG Dip Social Policy Admin; PG Dip HRM; Post Basic Public Health; BA Management/Sociology (double major); FRNOB A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2013 School of Population Health Abstract This thesis reports the findings of the first in-depth qualitative research on the socio-cultural perceptions of and responses to HIV and AIDS from the two selected tribes in rural Fiji. The study is guided by an ethnographic framework with grounded theory approach. Data was obtained using methods of Key Informants Interviews (KII), Focus Group Discussions (FGD), participant observations and documentary analysis of scripts, brochures, curriculum, magazines, newspapers articles obtained from a broad range of Fijian sources. The study findings confirmed that the Indigenous Fijian women population are aware of and concerned about HIV and AIDS. Specifically, control over their lives and decision-making is shaped by changes of vanua (land and its people), lotu (church), and matanitu (state or government) structures. This increases their vulnerabilities. Informants identified HIV and AIDS with a loss of control over the traditional way of life, over family ties, over oneself and loss of control over risks and vulnerability factors. The understanding of HIV and AIDS is situated in the cultural context as indigenous in its origin and required a traditional approach to management and healing. -

The Case for Lau and Namosi Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali

ACCOUNTABILITY IN FIJI’S PROVINCIAL COUNCILS AND COMPANIES: THE CASE FOR LAU AND NAMOSI MASILINA TUILOA ROTUIVAQALI ACCOUNTABILITY IN FIJI’S PROVINCIAL COUNCILS AND COMPANIES: THE CASE FOR LAU AND NAMOSI by Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Commerce Copyright © 2012 by Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali School of Accounting & Finance Faculty of Business & Economics The University of the South Pacific September, 2012 DECLARATION Statement by Author I, Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali, declare that this thesis is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published, or substantially overlapping with material submitted for the award of any other degree at any institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the text. Signature………………………………. Date……………………………… Name: Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali Student ID No: S00001259 Statement by Supervisor The research in this thesis was performed under my supervision and to my knowledge is the sole work of Mrs. Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali. Signature……………………………… Date………………………………... Name: Michael Millin White Designation: Professor in Accounting DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my beloved daughters Adi Filomena Rotuisolia, Adi Fulori Rotuisolia and Adi Losalini Rotuisolia and to my niece and nephew, Masilina Tehila Tuiloa and Malakai Ebenezer Tuiloa. I hope this thesis will instill in them the desire to continue pursuing their education. As Nelson Mandela once said and I quote “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The completion of this thesis owes so much from the support of several people and organisations. -

We Are Kai Tonga”

5. “We are Kai Tonga” The islands of Moala, Totoya and Matuku, collectively known as the Yasayasa Moala, lie between 100 and 130 kilometres south-east of Viti Levu and approximately the same distance south-west of Lakeba. While, during the nineteenth century, the three islands owed some allegiance to Bau, there existed also several family connections with Lakeba. The most prominent of the few practising Christians there was Donumailulu, or Donu who, after lotuing while living on Lakeba, brought the faith to Moala when he returned there in 1852.1 Because of his conversion, Donu was soon forced to leave the island’s principal village, Navucunimasi, now known as Naroi. He took refuge in the village of Vunuku where, with the aid of a Tongan teacher, he introduced Christianity.2 Donu’s home island and its two nearest neighbours were to be the scene of Ma`afu’s first military adventures, ostensibly undertaken in the cause of the lotu. Richard Lyth, still working on Lakeba, paid a pastoral visit to the Yasayasa Moala in October 1852. Despite the precarious state of Christianity on Moala itself, Lyth departed in optimistic mood, largely because of his confidence in Donu, “a very steady consistent man”.3 He observed that two young Moalan chiefs “who really ruled the land, remained determined haters of the truth”.4 On Matuku, which he also visited, all villages had accepted the lotu except the principal one, Dawaleka, to which Tui Nayau was vasu.5 The missionary’s qualified optimism was shattered in November when news reached Lakeba of an attack on Vunuku by the two chiefs opposed to the lotu. -

Reef Check Description of the 2000 Mass Coral Beaching Event in Fiji with Reference to the South Pacific

REEF CHECK DESCRIPTION OF THE 2000 MASS CORAL BEACHING EVENT IN FIJI WITH REFERENCE TO THE SOUTH PACIFIC Edward R. Lovell Biological Consultants, Fiji March, 2000 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................4 2.0 Methods.........................................................................................................................................4 3.0 The Bleaching Event .....................................................................................................................5 3.1 Background ................................................................................................................................5 3.2 South Pacific Context................................................................................................................6 3.2.1 Degree Heating Weeks.......................................................................................................6 3.3 Assessment ..............................................................................................................................11 3.4 Aerial flight .............................................................................................................................11 4.0 Survey Sites.................................................................................................................................13 4.1 Northern Vanua Levu Survey..................................................................................................13 -

The Case of Fiji

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 25 Issues 3&4 1992 Democracy and Respect for Difference: The Case of Fiji Joseph H. Carens University of Toronto Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Cultural Heritage Law Commons, Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Joseph H. Carens, Democracy and Respect for Difference: The Case of Fiji, 25 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 547 (1992). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol25/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEMOCRACY AND RESPECT FOR DIFFERENCE: THE CASE OF FIJI Joseph H. Carens* TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................. 549 I. A Short History of Fiji ................. .... 554 A. Native Fijians and the Colonial Regime .... 554 B. Fijian Indians .................. ....... 560 C. Group Relations ................ ....... 563 D. Colonial Politics ....................... 564 E. Transition to Independence ........ ....... 567 F. The 1970 Constitution ........... ....... 568 G. The 1987 Election and the Coup .... ....... 572 II. The Morality of Cultural Preservation: The Lessons of Fiji ................. ....... 574 III. Who Is Entitled to Equal Citizenship? ... ....... 577 A. The Citizenship of the Fijian Indians ....... 577 B. Moral Limits to Historical Appeals: The Deed of Cession ............. ....... 580 * Associate Professor of Political Science, University of Toronto. -

Severe Tc Gita (Cat4) Passes Just South of Ono

FIJI METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF FIJI MEDIA RELEASE No.35 5pm, Tuesday 13 February 2018 SEVERE TC GITA (CAT4) PASSES JUST SOUTH OF ONO Severe TC Gita (Category 4) entered Fiji Waters this morning and passed just south of Ono-i- lau at around 1.30pm this afternoon. Hurricane force winds of 68 knots and maximum momentary gusts of 84 knots were recorded at Ono-i-lau at 2pm this afternoon as TC Gita tracked westward. Vanuabalavu also recorded strong and gusty winds (Table 1). Severe “TC Gita” was located near 21.2 degrees south latitude and 178.9 degrees west longitude or about 60km south-southwest of Ono-i-lau or 390km southeast of Kadavu at 3pm this afternoon. It continues to move westward at about 25km/hr and expected to continue on this track and gradually turn west-southwest. On its projected path, Severe TC Gita is predicted to be located about 140km west-southwest of Ono-i-lau or 300km southeast of Kadavu around 8pm tonight. By 2am tomorrow morning, Severe TC Gita is expected to be located about 240km west-southwest of Ono-i-lau and 250km southeast of Kadavu and the following warnings remains in force: A “Hurricane Warning” remains in force for Ono-i-lau and Vatoa; A “Storm Warning” remains in force for the rest of Southern Lau group; A “Gale Warning” remains in force for Matuku, Totoya, Moala , Kadavu and nearby smaller islands and is now in force for Lakeba and Nayau; A “Strong Wind Warning” remains in force for Central Lau Group, Lomaiviti Group, southern half of Viti Levu and is now in force for rest of Fiji. -

Report SCEFI Evaluation Final W.Koekebakker.Pdf

Strengthening Citizen Engagement in Fiji Initiative (SCEFI) Final Evaluation Report Welmoed E. Koekebakker November, 2016 ATLAS project ID: 00093651 EU Contribution Agreement: FED/2013/315-685 Strengthening Citizen Engagement in Fiji Initiative (SCEFI) Final Evaluation Report Welmoed Koekebakker Contents List of acronyms and local terms iv Executive Summary v 1. Introduction 1 Purpose of the evaluation 1 Key findings of the evaluation are: 2 2. Strengthening Citizen Engagement in Fiji Initiative (SCEFI) 3 Intervention logic 4 Grants and Dialogue: interrelated components 5 Implementation modalities 6 Management arrangements and project monitoring 6 3. Evaluation Methodology 7 Evaluation Questions 9 4. SCEFI Achievements and Contribution to Outcome 10 A. Support to 44 Fijian CSOs: achievements, assessment 10 Quantitative and qualitative assessment of the SCEFI CSO grants 10 Meta-assessment 12 4 Examples of Outcome 12 Viseisei Sai Health Centre (VSHC): Empowerment of Single Teenage Mothers 12 Youth Champs for Mental Health (YC4MH): Youth empowerment 13 Pacific Centre for Peacebuilding (PCP) - Post Cyclone support Taveuni 14 Fiji’s Disabled Peoples Federation (FDPF). 16 B. Leadership Dialogue and CSO dialogue with high level stakeholders 16 1. CSO Coalition building and CSO-Government relation building 17 Sustainable Development Goals 17 Strengthening CSO Coalitions in Fiji 17 Support to National Youth Council of Fiji (NYCF) and youth visioning workshop 17 Civil Society - Parliament outreach 18 Youth Advocacy workshop 18 2. Peace and social cohesion support 19 Rotuma: Leadership Training and Dialogue for Chiefs, Community Leaders and Youth 19 Multicultural Youth Dialogues 20 Inter-ethnic dialogue in Rewa 20 Pacific Peace conference 21 3. Post cyclone support 21 Lessons learned on post disaster relief: FRIEND 21 Collaboration SCEFI - Ministry of Youth and Sports: Koro – cash for work 22 Transparency in post disaster relief 22 4. -

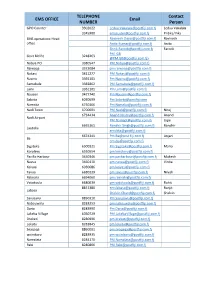

EMS Operations Centre

TELEPHONE Contact EMS OFFICE Email NUMBER Person GPO Counter 3302022 [email protected] Ledua Vakalala 3345900 [email protected] Pritika/Vika EMS operations-Head [email protected] Ravinesh office [email protected] Anita [email protected] Farook PM GB Govt Bld Po 3218263 @[email protected]> Nabua PO 3380547 [email protected] Raiwaqa 3373084 [email protected] Nakasi 3411277 [email protected] Nasinu 3392101 [email protected] Samabula 3382862 [email protected] Lami 3361101 [email protected] Nausori 3477740 [email protected] Sabeto 6030699 [email protected] Namaka 6750166 [email protected] Nadi Town 6700001 [email protected] Niraj 6724434 [email protected] Anand Nadi Airport [email protected] Jope 6665161 [email protected] Randhir Lautoka [email protected] 6674341 [email protected] Anjani Ba [email protected] Sigatoka 6500321 [email protected] Maria Korolevu 6530554 [email protected] Pacific Harbour 3450346 [email protected] Mukesh Navua 3460110 [email protected] Vinita Keiyasi 6030686 [email protected] Tavua 6680239 [email protected] Nilesh Rakiraki 6694060 [email protected] Vatukoula 6680639 [email protected] Rohit 8812380 [email protected] Ranjit Labasa [email protected] Shalvin Savusavu 8850310 [email protected] Nabouwalu 8283253 [email protected] -

Melanesia in Review: Issues and Events, 2000

Melanesia in Review: Issues and Events, 2000 Reviews of Papua New Guinea and tion of May 1999, became more overt West Papua are not included in this in the early months of 2000. Fijian issue. political parties, led by the former governing party, Soqosoqo ni Vakavu- Fi j i lewa ni Taukei (sv t), held meetings For the people of Fiji, the year 2000 around the country to discuss ways to was the most turbulent and traumatic oppose if not depose the government in recent memory. The country and thereby return to power. These endured an armed takeover of parlia- meetings helped fuel indigenous Fijian ment and a hostage crisis lasting fifty- unease and animosity toward Chaud- six days, the declaration of martial hry’s leadership. Signaling its move law and abrogation of the 1997 con- toward a more nationalist stance, the stitution, and a bloody mutiny in the sv t terminated its coalition with the armed forces. These events raised the Indo-Fijian–based National Federa- specter of civil war and economic col- tion Party in February, describing the lapse, international ostracism, and a coalition as “self-defeating.” future plagued with uncertainty and In March, the Taukei Movement ha r dship. Comparisons with the coups was revived with the aim, according of 1987 were inevitable, but most to spokesman Apisai Tora, of “rem o v - observers would conclude that the ing the government through various crisis of 2000 left Fiji more adrift legal means as soon as possible” (Sun, and divided than ever before. 3 May 2000, 1). In 1987 the Taukei The month of May has become Movement had spearheaded national- synonymous with coups in Fiji. -

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents Acknowledgements 1 Minister of Fisheries Opening Speech 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Executive Summary 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Background 9 2.1 The Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 9 2.2 The biological diversity of the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 11 3.0 Objectives of the FIME Biodiversity Visioning Workshop 13 3.1 Overall biodiversity conservation goals 13 3.2 Specifi c goals of the FIME biodiversity visioning workshop 13 4.0 Methodology 14 4.1 Setting taxonomic priorities 14 4.2 Setting overall biodiversity priorities 14 4.3 Understanding the Conservation Context 16 4.4 Drafting a Conservation Vision 16 5.0 Results 17 5.1 Taxonomic Priorities 17 5.1.1 Coastal terrestrial vegetation and small offshore islands 17 5.1.2 Coral reefs and associated fauna 24 5.1.3 Coral reef fi sh 28 5.1.4 Inshore ecosystems 36 5.1.5 Open ocean and pelagic ecosystems 38 5.1.6 Species of special concern 40 5.1.7 Community knowledge about habitats and species 41 5.2 Priority Conservation Areas 47 5.3 Agreeing a vision statement for FIME 57 6.0 Conclusions and recommendations 58 6.1 Information gaps to assessing marine biodiversity 58 6.2 Collective recommendations of the workshop participants 59 6.3 Towards an Ecoregional Action Plan 60 7.0 References 62 8.0 Appendices 67 Annex 1: List of participants 67 Annex 2: Preliminary list of marine species found in Fiji. 71 Annex 3 : Workshop Photos 74 List of Figures: Figure 1 The Ecoregion Conservation Proccess 8 Figure 2 Approximate -

Tuesday-27Th November 2018

PARLIAMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF FIJI PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DAILY HANSARD TUESDAY, 27TH NOVEMBER, 2018 [CORRECTED COPY] C O N T E N T S Pages Minutes … … … … … … … … … … 10 Communications from the Chair … … … … … … … 10-11 Point of Order … … … … … … … … … … 11-12 Debate on His Excellency the President’s Address … … … … … 12-68 List of Speakers 1. Hon. J.V. Bainimarama Pages 12-17 2. Hon. S. Adimaitoga Pages 18-20 3. Hon. R.S. Akbar Pages 20-24 4. Hon. P.K. Bala Pages 25-28 5. Hon. V.K. Bhatnagar Pages 28-32 6. Hon. M. Bulanauca Pages 33-39 7. Hon. M.D. Bulitavu Pages 39-44 8. Hon. V.R. Gavoka Pages 44-48 9. Hon. Dr. S.R. Govind Pages 50-54 10. Hon. A. Jale Pages 54-57 11. Hon. Ro T.V. Kepa Pages 57-63 12. Hon. S.S. Kirpal Pages 63-64 13. Hon. Cdr. S.T. Koroilavesau Pages 64-68 Speaker’s Ruling … … … … … … … … … 68 TUESDAY, 27TH NOVEMBER, 2018 The Parliament resumed at 9.36 a.m., pursuant to adjournment. HONOURABLE SPEAKER took the Chair and read the Prayer. PRESENT All Honourable Members were present. MINUTES HON. LEADER OF THE GOVERNMENT IN PARLIAMENT.- Madam Speaker, I move: That the Minutes of the sittings of Parliament held on Monday, 26th November 2018, as previously circulated, be taken as read and be confirmed. HON. A.A. MAHARAJ.- Madam Speaker, I beg to second the motion. Question put Motion agreed to. COMMUNICATIONS FROM THE CHAIR Welcome I welcome all Honourable Members to the second sitting day of Parliament for the 2018 to 2019 session.