Verbal Classifier Structures in the Wu Dialects of China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cantonese Opera and the Growth and Spread Of

Proceedings of the 29th North American Conference on Chinese Linguistics (NACCL-29). 2017. Volume 2. Edited by Lan Zhang. University of Memphis, Memphis, TN. Pages 533-544. Historical Change of Diminutives in Southern Wu Dialects Henghua Su Indiana University In many languages, diminutives are formed by adding affixes to the roots, while in different Southern Wu dialects, diminutives take various forms such as suffixation, nasal coda attachment, nasalization and purely tonal change. This paper argues that all these diminutive forms are derived from one single derivational process and the tonal change can be explained in terms of the tonal stability in autosegmental phonology from a historical development perspective. Data from different Southern Wu dialects show that all the diminutive forms presented above are actually derived from one historical changing process. This changing process can be explained with autosegmental representations. Also, geographic distribution of dialects may provide insights for the interactions of phonological features in these dialects. 0. Introduction Autosegmental phonology as a non-linear theory is developed on the discussion of tonal languages in Africa (Kenstowicz 1994). The independent behaviors of tones, such as floating tones and contour tones, provide abundant evidence for a non-linear relationship between tones and the tone bearing units (Clements, 1976. Goldsmith 1976; McCarthy, 1981, 1986; Kenstowicz, 1994; Ogden & Local 1994). Take contour tones as an example, they are best explained by the many-to-one relation between tonal features and TBUs. In a linear theory, this type of phenomenon violates the one-to-one relation between a feature and a segment. Besides African languages, many Asian languages are also tonal. -

Enhanced Magnetic Properties of Fesial Soft Magnetic Composites Prepared by Utilizing PSA As Resin Insulating Layer

polymers Article Enhanced Magnetic Properties of FeSiAl Soft Magnetic Composites Prepared by Utilizing PSA as Resin Insulating Layer Hao Lu 1,2, Yaqiang Dong 2,3,* , Xincai Liu 1,*, Zhonghao Liu 1,2, Yue Wu 2, Haijie Zhang 2, Aina He 2,3, Jiawei Li 2,3 and Xinmin Wang 2 1 Faculty of Materials Science and Chemical Engineering, Ningbo University, Ningbo 315211, China; [email protected] (H.L.); [email protected] (Z.L.) 2 Zhejiang Province Key Laboratory of Magnetic Materials and Application Technology, CAS Key Laboratory of Magnetic Materials and Devices, Ningbo Institute of Materials Technology & Engineering, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Ningbo 315201, China; [email protected] (Y.W.); [email protected] (H.Z.); [email protected] (A.H.); [email protected] (J.L.); [email protected] (X.W.) 3 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (Y.D.); [email protected] (X.L.) Abstract: Thermosetting organic resins are widely applied as insulating coatings for soft magnetic powder cores (SMPCs) because of their high electrical resistivity. However, their poor thermal stability and thermal decomposition lead to a decrease in electrical resistivity, thus limiting the annealing temperature of SMPCs. The large amount of internal stress generated by soft magnetic composites during pressing must be mitigated at high temperatures; therefore, it is especially important to find organic resins with excellent thermal stabilities. In this study, we prepared SMPCs using poly-silicon- Citation: Lu, H.; Dong, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, H.; He, A.; Li, containing arylacetylene resin, an organic resin resistant to high temperatures, as an insulating layer. -

Risk Factors for Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa, Zhejiang Province, China

Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2510.181699 Risk Factors for Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Zhejiang Province, China Appendix Appendix Table. Surveillance for carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in hospitals, Zhejiang Province, China, 2015– 2017* Years Hospitals by city Level† Strain identification method‡ excluded§ Hangzhou First 17 People's Liberation Army Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Red Cross Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou First People’s Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Hangzhou Children's Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Hospital of Chinese Traditional Hospital 3A Phoenix 100, VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Cancer Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Xixi Hospital of Hangzhou 3A VITEK 2 Compact Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University 3A MALDI-TOF MS The Children's Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine 3A MALDI-TOF MS Women's Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University 3A VITEK 2 Compact The First Affiliated Hospital of Medical School of Zhejiang University 3A MALDI-TOF MS The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of 3A MALDI-TOF MS Medicine Hangzhou Second People’s Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang People's Armed Police Corps Hospital, Hangzhou 3A Phoenix 100 Xinhua Hospital of Zhejiang Province 3A VITEK 2 Compact Zhejiang Provincial People's Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine 3A MALDI-TOF MS Tongde Hospital of Zhejiang Province 3A VITEK 2 Compact Zhejiang Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang Cancer -

Seazen Group Limited 新城發展控股有限公司

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. SEAZEN GROUP LIMITED 新城發展控股有限公司 (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) (Stock Code: 1030) ANNUAL RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2020 ANNUAL RESULTS HIGHLIGHTS – Contracted sales were approximately RMB250,963 million; – Rental and management fee income from Wuyue Plazas was approximately RMB5,309 million; – Revenue was approximately RMB146,119 million, representing a year-on-year growth of approximately 68.2%; – Net profit attributable to equity holders of the Company was approximately RMB10,178 million, representing a year-on-year increase of 30.3%; – Core earnings* attributable to equity holders of the Company was approximately RMB8,564 million, representing a year-on-year increase of 25.9%; – The net debt-to-equity ratio was 50.7% ; the cash** to short-term debt ratio was 2.03 times; – The contracted amount of pre-sold but not recognized properties was approximately RMB377,995 million, subject to further recognition; – The total gross floor area (“GFA”) of the land bank was approximately 143 million sq.m.; and – The Board recommended a payment of final dividends of RMB41 cents per share. * Core earnings equal to net profit less after-tax fair value gains or losses on investment properties and financial assets, and unrealized foreign exchange gains or losses relating to borrowings and financial assets and after-tax gains or losses on disposal of subsidiaries. -

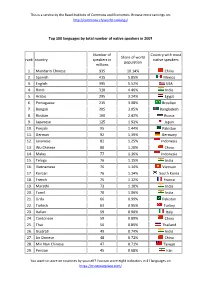

Top 100 Languages by Total Number of Native Speakers in 2007 Rank

This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. Browse more rankings on: http://commons.ch/world-rankings/ Top 100 languages by total number of native speakers in 2007 Number of Country with most Share of world rank country speakers in native speakers population millions 1. Mandarin Chinese 935 10.14% China 2. Spanish 415 5.85% Mexico 3. English 395 5.52% USA 4. Hindi 310 4.46% India 5. Arabic 295 3.24% Egypt 6. Portuguese 215 3.08% Brasilien 7. Bengali 205 3.05% Bangladesh 8. Russian 160 2.42% Russia 9. Japanese 125 1.92% Japan 10. Punjabi 95 1.44% Pakistan 11. German 92 1.39% Germany 12. Javanese 82 1.25% Indonesia 13. Wu Chinese 80 1.20% China 14. Malay 77 1.16% Indonesia 15. Telugu 76 1.15% India 16. Vietnamese 76 1.14% Vietnam 17. Korean 76 1.14% South Korea 18. French 75 1.12% France 19. Marathi 73 1.10% India 20. Tamil 70 1.06% India 21. Urdu 66 0.99% Pakistan 22. Turkish 63 0.95% Turkey 23. Italian 59 0.90% Italy 24. Cantonese 59 0.89% China 25. Thai 56 0.85% Thailand 26. Gujarati 49 0.74% India 27. Jin Chinese 48 0.72% China 28. Min Nan Chinese 47 0.71% Taiwan 29. Persian 45 0.68% Iran You want to score on countries by yourself? You can score eight indicators in 41 languages on https://trustyourplace.com/ This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. -

Tonatory Patterns in Taizhou Wu Tones

TONATORY PATTERNS IN TAIZHOU WU TONES Phil Rose Emeritus Faculty, Australian National University [email protected] ABSTRACT 台州 subgroup of Wu to which Huángyán belongs. The issue has significance within descriptive Recordings of speakers of the Táizhou subgroup of tonetics, tonatory typology and historical linguistics. Wu Chinese are used to acoustically document an Wu dialects – at least the conservative varieties – interaction between tone and phonation first attested show a wide range of tonatory behaviour [11]. One in 1928. One or two of their typically seven or eight finds breathy or ventricular phonation in groups of tones are shown to have what sounds like a mid- tones characterising natural tonal classes of Rhyme glottal-stop, thus demonstrating a new importance for phonotactics and Wu’s complex tone pattern in Wu tonatory typology. Possibly reflecting sandhi. One also finds a single tone characterised by gradual loss, larygealisation appears restricted to the a different non-modal phonation type [12]; or even north and north-west, and is absent in Huángyán two different non-modal phonation types in two dialect where it was first described. A perturbatory tones. However, the Huangyan-type tonation seems model of the larygealisation is tested in an to involve a new variation, with the same phonation experiment determining how much of the complete type in two different tones from the same historical tonal F0 contour can be restored from a few tonal category, thus prompting speculation that it centiseconds of modal F0 at Rhyme onset and offset. developed before the tonal split. The results are used both to acoustically quantify laryngealised tonal F0, with its problematic jitter and 2. -

New Constraints on Intraplate Orogeny in the South China Continent

Gondwana Research 24 (2013) 902–917 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Gondwana Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/gr Systematic variations in seismic velocity and reflection in the crust of Cathaysia: New constraints on intraplate orogeny in the South China continent Zhongjie Zhang a,⁎, Tao Xu a, Bing Zhao a, José Badal b a State Key Laboratory of Lithospheric Evolution, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100029, China b Physics of the Earth, Sciences B, University of Zaragoza, Pedro Cerbuna 12, 50009 Zaragoza, Spain article info abstract Article history: The South China continent has a Mesozoic intraplate orogeny in its interior and an oceanward younging in Received 16 December 2011 postorogenic magmatic activity. In order to determine the constraints afforded by deep structure on the for- Received in revised form 15 May 2012 mation of these characteristics, we reevaluate the distribution of crustal velocities and wide-angle seismic re- Accepted 18 May 2012 flections in a 400 km-long wide-angle seismic profile between Lianxian, near Hunan Province, and Gangkou Available online 18 June 2012 Island, near Guangzhou City, South China. The results demonstrate that to the east of the Chenzhou-Linwu Fault (CLF) (the southern segment of the Jiangshan–Shaoxing Fault), the thickness and average P-wave veloc- Keywords: Wide-angle seismic data ity both of the sedimentary layer and the crystalline basement display abrupt lateral variations, in contrast to Crustal velocity layering to the west of the fault. This suggests that the deformation is well developed in the whole of the crust Frequency filtering beneath the Cathaysia block, in agreement with seismic evidence on the eastwards migration of the orogeny Migration and stacking and the development of a vast magmatic province. -

Language Contact in Nanning: Nanning Pinghua and Nanning Cantonese

20140303 draft of : de Sousa, Hilário. 2015a. Language contact in Nanning: Nanning Pinghua and Nanning Cantonese. In Chappell, Hilary (ed.), Diversity in Sinitic languages, 157–189. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Do not quote or cite this draft. LANGUAGE CONTACT IN NANNING — FROM THE POINT OF VIEW OF NANNING PINGHUA AND NANNING CANTONESE1 Hilário de Sousa Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen, École des hautes études en sciences sociales — ERC SINOTYPE project 1 Various topics discussed in this paper formed the body of talks given at the following conferences: Syntax of the World’s Languages IV, Dynamique du Langage, CNRS & Université Lumière Lyon 2, 2010; Humanities of the Lesser-Known — New Directions in the Descriptions, Documentation, and Typology of Endangered Languages and Musics, Lunds Universitet, 2010; 第五屆漢語方言語法國際研討會 [The Fifth International Conference on the Grammar of Chinese Dialects], 上海大学 Shanghai University, 2010; Southeast Asian Linguistics Society Conference 21, Kasetsart University, 2011; and Workshop on Ecology, Population Movements, and Language Diversity, Université Lumière Lyon 2, 2011. I would like to thank the conference organizers, and all who attended my talks and provided me with valuable comments. I would also like to thank all of my Nanning Pinghua informants, my main informant 梁世華 lɛŋ11 ɬi55wa11/ Liáng Shìhuá in particular, for teaching me their language(s). I have learnt a great deal from all the linguists that I met in Guangxi, 林亦 Lín Yì and 覃鳳餘 Qín Fèngyú of Guangxi University in particular. My colleagues have given me much comments and support; I would like to thank all of them, our director, Prof. Hilary Chappell, in particular. Errors are my own. -

Shanghainese Vowel Merger Reversal Full Title

0 Short title: Shanghainese vowel merger reversal Full title: On the cognitive basis of contact-induced sound change: Vowel merger reversal in Shanghainese Names, affiliations, and email addresses of authors: Yao Yao The Hong Kong Polytechnic University [email protected] Charles B. Chang Boston University [email protected] Address for correspondence: Yao Yao The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Department of Chinese and Bilingual Studies Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong 1 Short title: Shanghainese vowel merger reversal Full title: On the cognitive basis of contact-induced sound change: Vowel merger reversal in Shanghainese 2 Abstract This study investigated the source and status of a recent sound change in Shanghainese (Wu, Sinitic) that has been attributed to language contact with Mandarin. The change involves two vowels, /e/ and /ɛ/, reported to be merged three decades ago but produced distinctly in contemporary Shanghainese. Results of two production experiments showed that speaker age, language mode (monolingual Shanghainese vs. bilingual Shanghainese-Mandarin), and crosslinguistic phonological similarity all influenced the production of these vowels. These findings provide evidence for language contact as a linguistic means of merger reversal and are consistent with the view that contact phenomena originate from cross-language interaction within the bilingual mind.* Keywords: merger reversal, language contact, bilingual processing, phonological similarity, crosslinguistic influence, Shanghainese, Mandarin. * This research was supported by -

De Sousa Sinitic MSEA

THE FAR SOUTHERN SINITIC LANGUAGES AS PART OF MAINLAND SOUTHEAST ASIA (DRAFT: for MPI MSEA workshop. 21st November 2012 version.) Hilário de Sousa ERC project SINOTYPE — École des hautes études en sciences sociales [email protected]; [email protected] Within the Mainland Southeast Asian (MSEA) linguistic area (e.g. Matisoff 2003; Bisang 2006; Enfield 2005, 2011), some languages are said to be in the core of the language area, while others are said to be periphery. In the core are Mon-Khmer languages like Vietnamese and Khmer, and Kra-Dai languages like Lao and Thai. The core languages generally have: – Lexical tonal and/or phonational contrasts (except that most Khmer dialects lost their phonational contrasts; languages which are primarily tonal often have five or more tonemes); – Analytic morphological profile with many sesquisyllabic or monosyllabic words; – Strong left-headedness, including prepositions and SVO word order. The Sino-Tibetan languages, like Burmese and Mandarin, are said to be periphery to the MSEA linguistic area. The periphery languages have fewer traits that are typical to MSEA. For instance, Burmese is SOV and right-headed in general, but it has some left-headed traits like post-nominal adjectives (‘stative verbs’) and numerals. Mandarin is SVO and has prepositions, but it is otherwise strongly right-headed. These two languages also have fewer lexical tones. This paper aims at discussing some of the phonological and word order typological traits amongst the Sinitic languages, and comparing them with the MSEA typological canon. While none of the Sinitic languages could be considered to be in the core of the MSEA language area, the Far Southern Sinitic languages, namely Yuè, Pínghuà, the Sinitic dialects of Hǎinán and Léizhōu, and perhaps also Hakka in Guǎngdōng (largely corresponding to Chappell (2012, in press)’s ‘Southern Zone’) are less ‘fringe’ than the other Sinitic languages from the point of view of the MSEA linguistic area. -

Official Colours of Chinese Regimes: a Panchronic Philological Study with Historical Accounts of China

TRAMES, 2012, 16(66/61), 3, 237–285 OFFICIAL COLOURS OF CHINESE REGIMES: A PANCHRONIC PHILOLOGICAL STUDY WITH HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS OF CHINA Jingyi Gao Institute of the Estonian Language, University of Tartu, and Tallinn University Abstract. The paper reports a panchronic philological study on the official colours of Chinese regimes. The historical accounts of the Chinese regimes are introduced. The official colours are summarised with philological references of archaic texts. Remarkably, it has been suggested that the official colours of the most ancient regimes should be the three primitive colours: (1) white-yellow, (2) black-grue yellow, and (3) red-yellow, instead of the simple colours. There were inconsistent historical records on the official colours of the most ancient regimes because the composite colour categories had been split. It has solved the historical problem with the linguistic theory of composite colour categories. Besides, it is concluded how the official colours were determined: At first, the official colour might be naturally determined according to the substance of the ruling population. There might be three groups of people in the Far East. (1) The developed hunter gatherers with livestock preferred the white-yellow colour of milk. (2) The farmers preferred the red-yellow colour of sun and fire. (3) The herders preferred the black-grue-yellow colour of water bodies. Later, after the Han-Chinese consolidation, the official colour could be politically determined according to the main property of the five elements in Sino-metaphysics. The red colour has been predominate in China for many reasons. Keywords: colour symbolism, official colours, national colours, five elements, philology, Chinese history, Chinese language, etymology, basic colour terms DOI: 10.3176/tr.2012.3.03 1. -

Materials on Forest Enets, an Indigenous Language of Northern Siberia

Materials on Forest Enets, an Indigenous Language of Northern Siberia SUOMALAIS-UGRILAISEN SEURAN TOIMITUKSIA MÉMOIRES DE LA SOCIÉTÉ FINNO-OUGRIENNE ❋ 267 ❋ Florian Siegl Materials on Forest Enets, an Indigenous Language of Northern Siberia SOCIÉTÉ FINNO-OUGRIENNE HELSINKI 2013 Florian Siegl: Materials on Forest Enets, an Indigenous Language of Northern Siberia Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Toimituksia Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne 267 Copyright © 2013 Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura — Société Finno-Ougrienne — Finno-Ugrian Society & Florian Siegl Layout Anna Kurvinen, Niko Partanen Language supervision Alexandra Kellner This study has been supported by Volkswagen Foundation. ISBN 978-952-5667-45-5 (print) MÉMOIRES DE LA SOCIÉTÉ FINNO-OUGRIENNE ISBN 978-952-5667-46-2 (online) SUOMALAIS-UGRILAISEN SEURAN TOIMITUKSIA ISSN 0355-0230 Editor-in-chief Riho Grünthal (Helsinki) Vammalan Kirjapaino Oy Editorial board Sastamala 2013 Marianne Bakró-Nagy (Szeged), Márta Csepregi (Budapest), Ulla-Maija Forsberg (Helsinki), Kaisa Häkkinen (Turku), Tilaukset — Orders Gerson Klumpp (Tartu), Johanna Laakso (Wien), Tiedekirja Lars-Gunnar Larsson (Uppsala), Kirkkokatu 14 Matti Miestamo (Stockholm), FI-00170 Helsinki Sirkka Saarinen (Turku), www.tiedekirja.fi Elena Skribnik (München), Trond Trosterud (Tromsø), [email protected] Berhard Wälchli (Stockholm), FAX +358 9 635 017 Jussi Ylikoski (Kautokeino) He used often to say there was only one Road; that it was like a great river: its springs were at every doorstep, and every path was its tributary. “It’s a dangerous business, Frodo, going out of your door,” he used to say. “You step into the Road, and if you don’t keep your feet, there is no knowing where you might be swept off to […]” (The Fellowship of the Ring, New York: Ballantine Books, 1982, 102).