West Elk Mountains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colorado Fourteeners Checklist

Colorado Fourteeners Checklist Rank Mountain Peak Mountain Range Elevation Date Climbed 1 Mount Elbert Sawatch Range 14,440 ft 2 Mount Massive Sawatch Range 14,428 ft 3 Mount Harvard Sawatch Range 14,421 ft 4 Blanca Peak Sangre de Cristo Range 14,351 ft 5 La Plata Peak Sawatch Range 14,343 ft 6 Uncompahgre Peak San Juan Mountains 14,321 ft 7 Crestone Peak Sangre de Cristo Range 14,300 ft 8 Mount Lincoln Mosquito Range 14,293 ft 9 Castle Peak Elk Mountains 14,279 ft 10 Grays Peak Front Range 14,278 ft 11 Mount Antero Sawatch Range 14,276 ft 12 Torreys Peak Front Range 14,275 ft 13 Quandary Peak Mosquito Range 14,271 ft 14 Mount Evans Front Range 14,271 ft 15 Longs Peak Front Range 14,259 ft 16 Mount Wilson San Miguel Mountains 14,252 ft 17 Mount Shavano Sawatch Range 14,231 ft 18 Mount Princeton Sawatch Range 14,204 ft 19 Mount Belford Sawatch Range 14,203 ft 20 Crestone Needle Sangre de Cristo Range 14,203 ft 21 Mount Yale Sawatch Range 14,200 ft 22 Mount Bross Mosquito Range 14,178 ft 23 Kit Carson Mountain Sangre de Cristo Range 14,171 ft 24 Maroon Peak Elk Mountains 14,163 ft 25 Tabeguache Peak Sawatch Range 14,162 ft 26 Mount Oxford Collegiate Peaks 14,160 ft 27 Mount Sneffels Sneffels Range 14,158 ft 28 Mount Democrat Mosquito Range 14,155 ft 29 Capitol Peak Elk Mountains 14,137 ft 30 Pikes Peak Front Range 14,115 ft 31 Snowmass Mountain Elk Mountains 14,099 ft 32 Windom Peak Needle Mountains 14,093 ft 33 Mount Eolus San Juan Mountains 14,090 ft 34 Challenger Point Sangre de Cristo Range 14,087 ft 35 Mount Columbia Sawatch Range -

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC)

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Summits on the Air USA - Colorado (WØC) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S46.1 Issue number 3.2 Date of issue 15-June-2021 Participation start date 01-May-2010 Authorised Date: 15-June-2021 obo SOTA Management Team Association Manager Matt Schnizer KØMOS Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Page 1 of 11 Document S46.1 V3.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Change Control Date Version Details 01-May-10 1.0 First formal issue of this document 01-Aug-11 2.0 Updated Version including all qualified CO Peaks, North Dakota, and South Dakota Peaks 01-Dec-11 2.1 Corrections to document for consistency between sections. 31-Mar-14 2.2 Convert WØ to WØC for Colorado only Association. Remove South Dakota and North Dakota Regions. Minor grammatical changes. Clarification of SOTA Rule 3.7.3 “Final Access”. Matt Schnizer K0MOS becomes the new W0C Association Manager. 04/30/16 2.3 Updated Disclaimer Updated 2.0 Program Derivation: Changed prominence from 500 ft to 150m (492 ft) Updated 3.0 General information: Added valid FCC license Corrected conversion factor (ft to m) and recalculated all summits 1-Apr-2017 3.0 Acquired new Summit List from ListsofJohn.com: 64 new summits (37 for P500 ft to P150 m change and 27 new) and 3 deletes due to prom corrections. -

THE GUNNISON RIVER BASIN a HANDBOOK for INHABITANTS from the Gunnison Basin Roundtable 2013-14

THE GUNNISON RIVER BASIN A HANDBOOK FOR INHABITANTS from the Gunnison Basin Roundtable 2013-14 hen someone says ‘water problems,’ do you tend to say, ‘Oh, that’s too complicated; I’ll leave that to the experts’? Members of the Gunnison Basin WRoundtable - citizens like you - say you can no longer afford that excuse. Colorado is launching into a multi-generational water planning process; this is a challenge with many technical aspects, but the heart of it is a ‘problem in democracy’: given the primacy of water to all life, will we help shape our own future? Those of us who love our Gunnison River Basin - the river that runs through us all - need to give this our attention. Please read on.... Photo by Luke Reschke 1 -- George Sibley, Handbook Editor People are going to continue to move to Colorado - demographers project between 3 and 5 million new people by 2050, a 60 to 100 percent increase over today’s population. They will all need water, in a state whose water resources are already stressed. So the governor this year has asked for a State Water Plan. Virtually all of the new people will move into existing urban and suburban Projected Growth areas and adjacent new developments - by River Basins and four-fifths of them are expected to <DPSDYampa-White %DVLQ Basin move to the “Front Range” metropolis Southwest Basin now stretching almost unbroken from 6RXWKZHVW %DVLQ South Platte Basin Fort Collins through the Denver region 6RXWK 3ODWWH %DVLQ Rio Grande Basin to Pueblo, along the base of the moun- 5LR *UDQGH %DVLQ tains. -

Final Report on the 2006 Ponderosa Campground Prescribed Burn Survey, Curecanti National Recreation Area, Gunnison County, Colorado

Final Report on the 2006 Ponderosa Campground Prescribed Burn Survey, Curecanti National Recreation Area, Gunnison County, Colorado Robert H. Brunswig, Ph.D. Anthropology Program School of Social Sciences University of Northern Colorado Greeley, Colorado 2006 Project Undertaken for the National Park Service as a partner of the Rocky Mountains Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (RM-CESU) RM-CESU Cooperative Agreement No. H1200040001 Executive Summary The University of Northern Colorado, under contract to the National Park Service, conducted an archeological survey of Ponderosa Campground, Curecanti National Recreation Area, on July 28, 2006. The survey was done as part of an archeological inventory for a larger prescribed burn program under the National Wildlife-Urban Interface (WUI) Program. One small prehistoric site and four isolated finds, associated with ephemeral hunting-gathering activities were documented. The survey’s documented cultural resources, when viewed locally and regionally, fit within an annual, seasonal cycle of subsistence procurement and processing common to the region over the past several millennia. ii Table of Contents Introduction....................................................................................................................... 1 Environmental Context .................................................................................................... 3 Geology............................................................................................................................... 3 Soils.................................................................................................................................... -

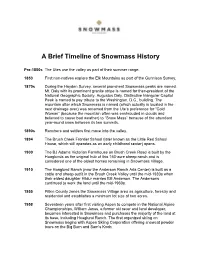

A Brief Timeline of Snowmass History

A Brief Timeline of Snowmass History Pre-1850s The Utes use the valley as part of their summer range. 1853 First non-natives explore the Elk Mountains as part of the Gunnison Survey. 1870s During the Hayden Survey, several prominent Snowmass peaks are named. Mt. Daly with its prominent granite stripe is named for then-president of the National Geographic Society, Augustus Daly. Distinctive triangular Capitol Peak is named to pay tribute to the Washington, D.C., building. The mountain after which Snowmass is named (which actually is located in the next drainage over) was renamed from the Ute’s preference for “Cold Woman” (because the mountain often was enshrouded in clouds and believed to cause bad weather) to “Snow Mass” because of the abundant year-round snow between its two summits. 1890s Ranchers and settlers first move into the valley. 1894 The Brush Creek Frontier School (later known as the Little Red School House, which still operates as an early childhood center) opens. 1900 The BJ Adams Victorian Farmhouse on Brush Creek Road is built by the Hoaglunds as the original hub of this 160-acre sheep ranch and is considered one of the oldest homes remaining in Snowmass Village. 1910 The Hoaglund Ranch (now the Anderson Ranch Arts Center) is built as a cattle and sheep outfit in the Brush Creek Valley until the mid-1930s when their eldest daughter Hildur marries Bill Anderson. The Andersons continued to work the land until the mid-1960s. 1955 Pitkin County zones the Snowmass Village area as agriculture, forestry and residential and establishes a minimum lot size of two acres. -

The Rockies of Colorado

THE ROCKIES OF COLORADO THE ROCKIES OF COLORADO BY EVELIO ECHEVARRfA C. (Three illustrations: nos. 9- II) OLORADO has always been proud of its mountains and rightly so; it is often referred to in the Union as 'the mountain state', about 6o per cent of its area is mountainous, and contains fifty-four peaks over 14,ooo ft. and some three hundred over 13,000 ft. Further, its mountaineering history has some unique aspects. And yet, Colorado's mountains have been seldom mentioned in mountaineering journals; if in modern times they may have deserved a passing mention it has been because of a new route on Long's Peak. But on the whole, the Rockies of Colorado are almost unrecorded in the mountaineering world abroad. In this paper, an effort has been made to outline briefly the characteris tics of this area, and to review its mountaineering past; a few personal experiences are also added. The mountains of Colorado belong almost completely to the Rocky Mountain range of North America; a few outliers are sometimes mentioned as independent lesser chains, but in features and heights they are unimportant. The Rockies of Colorado are grouped into a number of ranges (see sketch-map), some of which are actually prolongations of others. Some what loosely and with some injustice to precise geography, they can be grouped into ten important sections. The state of Colorado is a perfect rectangle in shape; the Rockies enter into its western third from Wyoming, to the north, and split, then, into two parallel chains which unite in the centre of the state. -

The Proposed Gunnison Forest Reserve, Colorado

THE PROPOSED GUNNISON FOREST RESERVE COLORADO _________ Examination, Report, and Recommendations By Smith Riley _________ Bureau of Forestry U.S. Department of Agriculture 1904 A facsimile of a copy acquired from the National Archives and Records Administration, Rocky Mountain Regional Office at Denver Federal Center February 24, 2005 by David Bradford. 1 The Proposed Gunnison Forest Reserve, Colorado ________ Location – Area – Topography The proposed Gunnison Forest Reserve is in Central Western Colorado, lying mostly in the Gunnison County with small projections into Delta and Montrose Counties. Designed largely to protect the flow of the Gunnison River, it covers the northern and eastern watershed of that stream, including the West Elk Mountains, Fossil Ridge, and all the mountainous area on the headwaters of Taylor and East Rivers. It contains 929,704 acres, and is 72 miles from east to west and 36 miles from north to south. The larger portion of the Tin Cup, Italian Mountain, Crested Butte, and Sunset mining districts are within the area. Only mountain lands are included, the higher points being between 13,000 and 14,000 feet in altitude, and the lowest limits between 7,000 and 8,000 feet. With the exception of the Taylor Park district and the Black Mesa, just above the Gunnison Canon, the entire area is rough in the extreme and difficult to traverse. The streams rising in the West Elk Mountains flow in deep rough canons which divide the lower south and west slopes into many mesas. The Taylor Park district is precipitous along the divide, and breaks off to tough mountainous country just above the south line of the reserve. -

Landscape Character Descriptions of the White River National Forest

Final Environmental Impact Statement Volume 3 Landscape Character Descriptions of the White River National Forest Headwaters of the South Fork of the White River Jan Spencer – Landscape Architect Writer/Editor Ron Wright – Soil Scientist Bill Kight – Heritage Resource Manager Kit Buell – Wildlife Biologist Carolyn Upton – Social/Economics Specialist Marsha Raus – Fisheries Biologist Narrative and Photography Contributors: Ron Taussig, Beth Boyst, George Myser, Tom Kuekes, Al Grimshaw, Dan Mathews, Paula Johnston, Kathy Hardy, Angela Glenn, Gary Osier P-1 Appendix P White River National Forest Preface The word landscape evokes certain unique and special images and meanings to each of us as individuals. As children we may have attached a sense of place to some small parcel of ground, be it a backyard or an open meadow blooming with the rainbow color of wildflowers. The rest of our lives then build upon those early impressions, layer upon layer of geographic recognition. Year after year we go back to a stream, yet each time we fish there we read something new into the landscape. It may even be some picnic spot with a backdrop of mountain majesty we can still see in our mind even with our eyes closed. These places uplift our spirit, but we are hard-pressed to put into words exactly how or why we feel the way we do. The comforting sense of familiarity a prominent granite peak holds for us never quite gets communicated beyond the photo image. “Like all real treasures of the mind, perception can be split into infinitely small fractions without losing its quality. -

Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forests Coal

Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forests Coal Resource and Development Potential Report (2004, revised 2006) ii TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 1 Purpose and Scope .......................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgments........................................................................................................... 1 II. Geologic Units............................................................................................................... 1 Description.................................................................................................................. 5 III. Coal Fields .................................................................................................................... 5 Carbondale Coal Field .................................................................................................... 6 Crested Butte Coal Field................................................................................................. 6 Grand Mesa Coal Field ................................................................................................... 8 Somerset Coal Field........................................................................................................ 8 Tongue Mesa Coal Field................................................................................................. 9 IV. Coal Characteristics -

NMGS 32Nd Field Conference

West Elk Breccia volcaniclastic facies in amphitheatre on north side of Mill Creek Canyon, West Elk volcanic field. Courtesy D. L. Gas kill, U.S. Geological Survey. "The hills west of Ohio Creek are composed mainly of breccia . eroded in the most fantastic fashion. The breccia is stratified, and there are huge castle-like forms, abrupt walls, spires, and towers." A. C. Peale, Hayden Survey, 1876 Editors RUDY C. EPIS and ONATHA ALLE.NDER Managing Editor JONATHAN F. CALLENDER A 44. iv CONTENTS Presidents Message vi Editors Message vi Committees vii Field Conference Schedule viii Field Trip Routes ix LANDSAT Photograph of Conference Area ROAD LOGS First Day: Road Log from Grand Junction to Whitewater, Unaweep Canyon, Uravan, Paradox Valley, La Sal, Arches National Park, and Return to Grand Junction via Crescent Junction, Utah C. M. Molenaar, L. C. Craig, W. L. Chenoweth, and I. A. Campbell 1 Second Day: Road Log from Grand Junction to Glenwood Canyon and Return to Grand Junction R. G. Young, C. W. Keighin and I. A. Campbell 17 Third Day: Road Log from Grand Junction to Crested Butte via Delta, Montrose and Gunnison C. S. Goodknight, R. D. Cole, R. A. Crawley, B. Bartleson and D. Gaskill 29 Supplemental Road Log No. 1: Montrose to Durango, Colorado K. Lee, R. C. Epis, D. L. Baars, D. H. Knepper and R. M. Summer 48 Supplemental Road Log No. 2: Gunnison to Saguache, Colorado R. C. Epis 64 ARTICLES Stratigraphy and Tectonics Stratigraphic Correlation Chart for Western Colorado and Northwestern New Mexico M. E. MacLachlan 75 Summary of Paleozoic Stratigraphy and History of Western Colorado and Eastern Utah John A. -

Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forests REVISED DRAFT Forest Assessments: Identifying and Assessing At-Risk Species March 2018

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forests REVISED DRAFT Forest Assessments: Identifying and Assessing At-Risk Species March 2018 American marten observed resting in a northern goshawk nest, in a lodgepole pine-Engelmann spruce forest on the Gunnison Ranger District. Biologists were visiting the goshawk nest site to check for occupancy and found this marten instead. In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. -

Historical Activity, 2 Wells Are Forecast to Be Abandoned Over the Next 15 Years

OIL AND GAS POTENTIAL AND REASONABLE FORESEEABLE DEVELOPMENT (RFD) SCENARIOS IN THE GRAND MESA, UNCOMPAHGRE, AND GUNNISON (GMUG) NATIONAL FORESTS COLORADO Bruce Fowler Pat Gallagher Bureau of Land Management Bureau of Land Management Geologist Petroleum Engineer August 27, 2004 Table of Contents SUMMARY ………………………………………………………………………… 3 INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………………………… 3 OIL AND GAS RESOURCE POTENTIAL …………………………………….. 6 Geology, USGS Assessment, Gas Fields – Piceance Basin ……………………… 7 Geology, USGS Assessment, Gas Fields – Paradox Basin ……………………… 19 Oil and Gas Occurrence Potential ………………………………………………. 23 SCENARIO FOR FUTURE OIL AND GAS EXPLORATION AND DEVELOPMENT ACTIVITY …………………………………………………… 29 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………. 29 Historical Development and Overview …………………………………………. 31 Present GMUG Condition ………………………………………………………. 33 Recent Exploration/Development Trends ……………………………………… 36 Trends – Gas Price and Drilling ………………………………………………… 40 GMUG Reasonable Foreseeable Development (RFD) ………………………… 44 APPENDIX 1. Classification of Oil and Gas Potential ……………………….. 48 CONTACTS ……………………………………………………………………… 49 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ……………………………………….. 50 GLOSSARY ……………………………………………………………………… 51 REFERENCES …………………………………………………………………… 52 2 SUMMARY Areas of the GMUG considered to have moderate to high potential for oil and gas occurrence are the Grand and Battlements Mesas, the Upper North Fork of the Gunnison River Valley (where the Mesaverde Formation is present, excluding the West Elk and Ragged Mountains), and the southwestern