Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Species Dossier

Pallavicinia lyellii Veilwort PALLAVICINIACEAE SYN: Pallavicinia lyellii (Hook.) Caruth. Status UK BAP Priority Species Lead Partner: Plantlife International & RBG, Kew Vulnerable (2001) Natural England Species Recovery Programme Status in Europe - Vulnerable 14 10km squares UK Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP) These are the current BAP targets following the 2001 Targets Review: T1 - Maintain populations of Veilwort at all extant sites. T2 - Increase the extent of Veilwort populations at all extant sites where appropriate and biologically feasible. T3 - If biologically feasible, re-establish populations of Veilwort at three suitable sites by 2005. T4 - Establish by 2005 ex situ stocks of this species to safeguard extant populations. Progress on targets as reported in the UKBAP 2002 reporting round can be viewed online at: http://www.ukbap.org.uk/2002OnlineReport/mainframe.htm. The full Action Plan for Pallavicinia lyellii can be viewed on the following web site: http://www.ukbap.org.uk/UKPlans.aspx?ID=497. Work on Pallavicinia lyellii is supported by: 1 Contents 1 Morphology, Identification, Taxonomy & Genetics................................................2 2 Distribution & Current Status ...........................................................................4 2.1 World ......................................................................................................4 2.2 Europe ....................................................................................................4 2.3 Britain .....................................................................................................5 -

Peatlands & Climate Change Action Plan 2030 Pages 0-15

Peatlands and Climate Change Action Plan 2030 © Irish Peatland Conservation Council 2021 Published by: Irish Peatland Conservation Council, Bog of Allen Nature Centre, Lullymore, Rathangan, Co. Kildare R51V293. Telephone: +353-45-860133 Email: [email protected] Web: www.ipcc.ie Written and compiled by: Dr Catherine O’Connell BSc, HDipEdn, PhD; Nuala Madigan BAgrEnvSc, MEd; Tristram Whyte BSc Hons Freshwater Biology and Paula Farrell BSc Wildlife Biology on behalf of the Irish Peatland Conservation Council. Irish Peatland Conservation Council Registered Revenue Charity Number CHY6829 and Charities Regulator Number (RCN) 20013547 ISBN 1 874189 34 X All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise with the prior permission of the Irish Peatland Conservation Council. Funded by: This Action Plan was funded by the Irish Peatland Conservation Council’s supporters - friends of the bog - who made donations in response to a spring appeal launched by the charity in 2020. Printing costs for the Action Plan were supported by the Heritage Council through their Heritage Sector Support Grant 2021. Copyright Images: Every effort has been made to acknowledge and contact copyright holders of all images used in this publication. Cover Image: Blanket bog complex south of Killary Harbour, Co. Galway. Blanket bogs face a number of pressures - overgrazing, drainage for turf cutting and forestry, burning to improve grazing, recreation and windfarm developments. Together these uses can change the natural function of the blanket bog so that it switches from slowing climate change as a carbon sink, to become a carbon source that releases greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. -

Controlling the Invasive Moss Sphagnum Palustre at Ka'ala

Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI`I AT MĀNOA Dr. David C. Duffy, Unit Leader Department of Botany 3190 Maile Way, St. John #408 Honolulu, Hawai’i 96822 Technical Report 192 Controlling the invasive moss Sphagnum palustre at Ka‘ala, Island of O‘ahu March 2015 Stephanie Marie Joe 1 1 The Oahu Army Natural Resource Program (OANRP) USAG-HI, Directorate of Public Works Environmental Division IMPC-HI-PWE 947 Wright Ave., Wheeler Army Airfield, Schofield Barracks, HI 96857-5013 [email protected] PCSU is a cooperative program between the University of Hawai`i and U.S. National Park Service, Cooperative Ecological Studies Unit. Organization Contact Information: Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit, Department of Botany, 3190 Maile Way, St. John #408, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI 96822. Office: (808) 753-0702. Recommended Citation: Joe, SM. 2015. Controlling the invasive moss Sphagnum palustre at Ka‘ala, Island of O‘ahu. Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit Technical Report 191. University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Department of Botany. Honolulu, HI. 18 pages. Key words: Bryocides, Sphagnum palustre, invasive species control Place key words: Pacific islands, O‘ahu, Ka‘ala Natural Area Reserve Editor: David C. Duffy, PCSU Unit Leader (Email: [email protected]) Series Editor: Clifford W. Morden, PCSU Deputy Director (Email: [email protected]) About this technical report series: This technical report series began in 1973 with the formation of the Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit at the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa. In 2000, it continued under the Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit (PCSU). The series currently is supported by the PCSU. -

TAXON:Sphagnum Palustre L. SCORE:11.0 RATING

TAXON: Sphagnum palustre L. SCORE: 11.0 RATING: High Risk Taxon: Sphagnum palustre L. Family: Sphagnaceae Common Name(s): boat-leaved sphagnum Synonym(s): Sphagnum cymbifolium (Ehrhart) R. Hedwig peat moss praire sphagnum spoon-leaved sphagnum Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 17 Sep 2019 WRA Score: 11.0 Designation: H(Hawai'i) Rating: High Risk Keywords: Dioecious Moss, Environmental Weed, Shade-Tolerant, Dense Mats, Spreads Vegetatively Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) Intermediate tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 n Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 y 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 n 402 Allelopathic y=1, n=0 y 403 Parasitic y=1, n=0 n 404 Unpalatable to grazing animals y=1, n=-1 y 405 Toxic to animals y=1, n=0 n 406 Host for recognized pests and pathogens 407 Causes allergies or is otherwise toxic to humans y=1, n=0 n 408 Creates a fire hazard in natural ecosystems y=1, n=0 n Creation Date: 17 Sep 2019 (Sphagnum palustre L.) Page 1 of 19 TAXON: Sphagnum palustre L. -

Sphagnum Palustre

Sphagnum palustre Britain 1990–2013 1358 1950–1989 337 pre-1950 42 Ireland 1990–2013 332 1950–1989 122 pre-1950 2 oose cushions and patches of Sphagnum palustre are have leaf cross-sections of intermediate and unstable L found in a wide variety of habitats, including wet woods, shape, differing between leaves on the same plant. Var. boggy grassland, ditches, flushed peaty banks, marshes and centrale has been found in four places in England, two in streamsides. Unlike S. papillosum, it is tolerant of shade and Wales, two in the Isle of Man, and as two separate gatherings is sometimes abundant in damp conifer plantations and from the Morrone Birkwood near Braemar in eastern swampy carr. It is one of the less acid-demanding sphagna, Scotland. The Morrone locality is at about 500 m altitude growing with S. fimbriatum, S. squarrosum and S. subnitens. and is the only one that fits with its distribution in Eurasia It is also common on oceanic blanket bogs, where it occupies and North America, where it has a continental distribution, small declivities receiving surface flow in wet weather. penetrating continental interiors from which var. palustre is Altitudinal range: 0–1100 m. absent. Genetic analysis in North America (Karlin et al., 2010) indicates that there is a clear distinction between the Dioicous; capsules are occasional, August. two taxa. Photos in Flatberg (2013) and Hölzer (2010) show S. centrale as remaining greenish or yellowish in autumn, and Plants in our area are mostly var. palustre. Var. centrale is not turning pinkish as is normal for var. -

Opportunities and Challenges of Sphagnum Farming & Harvesting

Opportunities and Challenges of Sphagnum Farming & Harvesting Gilbert Ludwig Master’s thesis December 2019 Bioeconomy Master of Natural Resources, Bioeconomy Development Description Author(s) Type of publication Date Ludwig, Gilbert Master’s thesis December 2019 Language of publication: English Number of pages Permission for web 33 publication: x Title of publication Opportunities & Challenges of Sphagnum Farming & Harvesting Master of Natural Resources, Bioeconomy Development Supervisor(s) Kataja, Jyrki; Vertainen, Laura; Assigned by International Peatland Society Abstract Sphagnum sp. moss, of which there are globally about 380 species, are the principal peat forming organisms in temperate and boreal peatlands. Sphagnum farming & harvesting has been proposed as climate-smart and carbon neutral use and after-use of peatlands, and dried Sphagnum have been shown to be excellent raw material for most growing media applications. The state, prospects and challenges of Sphagnum farming & harvesting in different parts of the world are evaluated: Sphagnum farming as paludiculture and after-use of agricultural peatlands and cut-over bogs, Sphagnum farming on mineral soils and mechanical Sphagnum harvesting. Challenges of Sphagnum farming and harvesting as a mean to reduce peat dependency in growing media are still significant, with industrial upscaling, i.e. ensuring adequate quantities of raw material, and economic feasibility being the biggest barriers. Development of new, innovative business models and including Sphagnum in the group of agricultural -

Edited by IJ Bennallick & DA Pearman

BOTANICAL CORNWALL 2010 No. 14 Edited by I.J. Bennallick & D.A. Pearman BOTANICAL CORNWALL No. 14 Edited by I.J.Bennallick & D.A.Pearman ISSN 1364 - 4335 © I.J. Bennallick & D.A. Pearman 2010 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the copyright holder. Published by - the Environmental Records Centre for Cornwall & the Isles of Scilly (ERCCIS) based at the- Cornwall Wildlife Trust Five Acres, Allet, Truro, Cornwall, TR4 9DJ Tel: (01872) 273939 Fax: (01872) 225476 Website: www.erccis.co.uk and www.cornwallwildlifetrust.org.uk Cover photo: Perennial Centaury Centaurium scilloides at Gwennap Head, 2010. © I J Bennallick 2 Contents Introduction - I. J. Bennallick & D. A. Pearman 4 A new dandelion - Taraxacum ronae - and its distribution in Cornwall - L. J. Margetts 5 Recording in Cornwall 2006 to 2009 – C. N. French 9 Fitch‟s Illustrations of the British Flora – C. N. French 15 Important Plant Areas – C. N. French 17 The decline of Illecebrum verticillatum – D. A. Pearman 22 Bryological Field Meetings 2006 – 2007 – N. de Sausmarez 29 Centaurium scilloides, Juncus subnodulosus and Phegopteris connectilis rediscovered in Cornwall after many years – I. J. Bennallick 36 Plant records for Cornwall up to September 2009 – I. J. Bennallick 43 Plant records and update from the Isles of Scilly 2006 – 2009 – R. E. Parslow 93 3 Introduction We can only apologise for the very long gestation of this number. There is so much going on in the Cornwall botanical world – a New Red Data Book, an imminent Fern Atlas, plans for a new Flora and a Rare Plant Register, plus masses of fieldwork, most notably for Natural England for rare plants on SSSIs, that somehow this publication has kept on being put back as other more urgent tasks vie for precedence. -

A History of Recording Bog Mosses in Berkshire with Selected Site Descriptions A

A History of Recording Bog Mosses in Berkshire with selected Site Descriptions A. Sanders Summary For a paper recently submitted for consideration to the Journal of Bryology, based on my dissertation for an MSc in Biological Recording from the University of Birmingham, I looked at the different methods of detecting change in species distribution over time in relation to bog mosses (Sphagnum spp.) in Vice County 22 (Berkshire). In this paper I will give a brief overview of the history of recording bryophytes (mosses and liverworts) in Berkshire and go on to describe some of the sites I have surveyed, the Sphagnum species to be found there and any changes that have taken place over the known recorded history. Introduction Sphagnum records for Berkshire were collected from a range of sources for my dissertation, as shown in Table 1, including herbaria at The University of Reading, RNG and The National Museum of Wales, NMW; these tended to be from pre-1945 or shortly after and had only a site name for location. The use of herbarium and museum specimens as a source of historical information for education and research, as resources for taxonomic study and as a means of assessing changes in species distribution is well documented (McCarthy 1998, Shaffer et al. 1998, Winker 2004, Pyke & Ehrlich 2010, Godfrey 2011, Colla et al. 2012, Culley 2013, Lavoie 2013, Nelson et al. 2013) and has seen a significant increase in research in the last twenty years (Pyke & Ehrlich 2010) because “collections represent both spatially and temporally precise data, they can be used to reconstruct historical species ranges....” (Drew 2011, p.1250). -

IVC) Community Synopsis

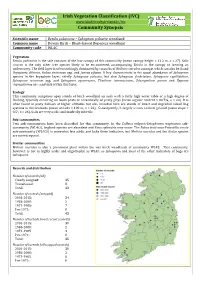

Irish Vegetation Classification (IVC) www.biodiversityireland.ie/ivc Community Synopsis Scientific name Betula pubescens – Sphagnum palustre woodland Common name Downy Birch – Blunt-leaved Bog-moss woodland Community code WL4C Vegetation Betula pubescens is the sole constant of the low canopy of this community (mean canopy height = 12.2 m, n = 27). Salix cinerea is the only other tree species likely to be encountered, accompanying Betula in the canopy or forming an understorey. The field layer is often strikingly dominated by tussocks of Molinia caerulea, amongst which can also be found Dryopteris dilatata, Rubus fruticosus agg. and Juncus effusus. A key characteristic is the usual abundance of Sphagnum species in the bryophyte layer, chiefly Sphagnum palustre, but also Sphagnum fimbriatum, Sphagnum capillifolium, Sphagnum recurvum agg. and Sphagnum squarrosum. Thuidium tamariscinum, Scleropodium purum and Hypnum cupressiforme are constants within this layer. Ecology This community comprises open stands of birch woodland on soils with a fairly high water table or a high degree of flushing, typically occurring on basin peats or occasionally on peaty gleys (mean organic content = 83.7%, n = 23). It is often found in peaty hollows at higher altitudes but also included here are stands of intact and degraded raised bog systems in the lowlands (mean altitude = 100 m, n = 26). Consequently, it largely occurs on level ground (mean slope = 0.5°, n = 26). Soils are very acidic and markedly infertile. Sub-communities Two sub-communities have been described for this community. In the Calluna vulgaris-Eriophorum vaginatum sub- community (WL4Ci), bogland species are abundant and Pinus sylvestris may occur. -

Topic- Sphagnum

Topic- Sphagnum Subject- Botany Author- Dr Surendra kumar Prasad Associate Professor in Botany Magadh Mahila College, Patna Email - surendra [email protected] Course- Bsc part I Paper II content .i. Morphology ii. ecology iii. economic Importance iv. water conducting mechanism v. Sphagnum as regarded as synthetic group System position class-Bryopsida Subclass-Sphagnidae order-sphagnales Family-Sphagniceae Morphology genus- Sphagnum i. Sphagnum represents Pet or Bog moss growing in ponds or moist place at high altitude including Himalaya. It render the water acidic and has an antiseptic value. ii. The upright gametophores radially arranged ,leaves leafy branches and without rhizoids. iii. Erect and pendent branches arises from the axil of a very fourth leaves. The erect branches are crowded and yet the top as comma or head while too much elongated pendent branches forming the loose mental around the stem axis at its proximal end. iv. The stem axis is solid ,delicate ,cylindrical smooth, porous and distinct ,node and internode. v. The stem tip terminate in a dense cluster of stout branches of limited growth. Such cluster constitute head or comma which is mean to protect apical bud. vi. The leafy branches in axis arises in a fiscal of 5 or even more than eight from the axils of fourth leaf on the stem axis .They are dimorphic. vii. The divergent branches are sort ,stout, extending outward horizontally upward slightly. viii. Pendent or flagellate form branches ,long,cylinder and droping by virtue of forming close association around the axis.Such branches constitute capillary system being helpful in ascending of water ix. -

Record Growth of Sphagnum Papillosum in Georgia (Transcaucasus): Rain Frequency, Temperature and Microhabitat As Key Drivers in Natural Bogs

Record growth of Sphagnum papillosum in Georgia (Transcaucasus): rain frequency, temperature and microhabitat as key drivers in natural bogs M. Krebs, G. Gaudig and H. Joosten Ernst Moritz Arndt University Greifswald, Partner in the Greifswald Mire Centre, Germany _______________________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY (1) Peatmoss (Sphagnum) growth has been studied widely, in particular at temperate and boreal latitudes > 45 °N, where productivity is mainly controlled by mean annual temperature and precipitation. We studied the growth of Sphagnum papillosum and S. palustre in four peatlands in the year-round warm and humid Kolkheti Lowlands (Georgia, Transcaucasus, eastern end of the Black Sea, latitude 41–42 °N). (2) Productivity, site conditions and climate in Kolkheti are included in a worldwide analysis of studies on the growth of S. papillosum to identify driving factors for its growth. (3) The productivity of S. papillosum and S. palustre under natural conditions is extraordinarily high in Kolkheti, reaching 269–548 g m-2 yr-1 and 387–788 g m-2 yr-1 (mean of various sites), respectively. Rates of increase in length are up to 30.3 cm yr-1, with the largest values for S. palustre. (4) Rate of increase in length and biomass productivity differed between years, with better growth being explained by higher number of rain days and shorter periods without precipitation. Regular rainfall is essential for continuous Sphagnum growth as low water table prevents permanent water supply by capillary rise. (5) The analysis of international studies on Sphagnum papillosum productivity confirms the decisive role of rain frequency, next to microhabitat. Productivity increases further with mean temperature during growth periods, the near-largest values being for Kolkheti. -

New Vice-County Records and Amendments to the Census Catalogue

Field Bryology number 93 New vice-county records and amendments to the Census Catalogue Hepaticae T.H. Blackstock Countryside Council for Wales, Plas Penrhos, Ffordd Penrhos, Bangor, Gwynedd LL57 2LQ 5.1. Trichocolea tomentella. 21: in a small current of water, 17.2. Odontoschisma denudatum. 57: on bare peat on steep which runs through a wood called Old Fall [Coldfall moorland bank by track, ca 325 m alt., northern slopes Wood], that lies between Highgate and Muscle Hill of Bleaklow, Woodhead Reservoir, SK086990, 2006, [Muswell Hill], TQ29, 1722, Dandridge, det. S.O. Blockeel 35/237. Lindberg (Druce & Vines, 1907; Dillenius in Ray, 17.3. Odontoschisma elongatum. 107: flush, by Gorm-loch 1724), comm. Hill. Beag, Skinsdale SSSI, NC705269, 2006, Lawley. 7.3. Kurzia trichoclados. 107: peaty bank, Raven’s Rock, 18.7. Cephaloziella stellulifera. 92: steep limestone slope Rosehall, near Altass, NC497011, 2006, Lawley. H8: with Betula, ca 400 m alt., E slope of Creag a’ Chlamhain, wet ground by forestry track, ca 300 m alt., Black Rock, NO26859547, 2006, Long 35610. Ballyhoura Mountains, R6418, 2005, Hodgetts 6040. 18.9. Cephaloziella nicholsonii. 46: on damp mortar 10.6. Calypogeia sphagnicola. 107: on Sphagnum low on slaty wall inside ruin of mine building, E of capillifolium on blanket bog, 390 m alt., Knockfin Cwmystwyth, SN802745, 1998, Holyoak 98-394, conf. Heights, NC90713353, 2006, Bosanquet. Paton. H3: patches on unshaded mainly bare damp sandy 10.7. Calypogeia suecica. 107: rotting log in ravine, soil of flushed area below old copper mine workings, ca upstream of viewpoint at Raven’s Rock, Altass, NC4901, 98 m alt., Allihies, V58954561, 2006, Holyoak 06-102, 2006, Preston.