Print Version (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Read Article As

He can see through walls, His Helmet is video-connected, and His rifle Has computer precision. We cHeck out tHe science (and explosive poWer) beHind tHe technology tHat’s making tHe future of the military into Halo come to life. by StinSon Carter illustration by kai lim want the soldier to think of himself as the $6 battalions. Today we fight with Small Tactical Units. Million Man,” says Colonel Douglas Tamilio, And the heart of the Small Tactical Unit is the single project manager of Soldier Weapons for the U.S. dismounted soldier. Army. In case you haven’t heard, the future of In Afghanistan, as in the combat zones of the fore warfare belongs to the soldier. The Civil War was fought seeable future, we will fight against highly mobile, by armies. World War II was fought by divisions. Viet highly adaptive enemies that blend seamlessly into nam was fought by platoons. Operation Desert Storm their environments, whether that’s a boulderstrewn was fought by brigades and the second Iraq war by mountainside or the densely populated urban jungle. enhanced coMbaT heLMeT Made from advanced plastics rather than Kevlar, the new ECH offers 35 percent more protection GeneraTion ii than current helmets. heLMeT SenSor The Gen II HS provides the wearer with analysis of explosions and any neTT Warrior other potential source This system is designed to provide of head trauma. vastly increased situational awareness on the battlefield, allowing combat leaders to track the locations and health ModuLar of their teams, who are viewing tactical LiGhTWeiGhT information via helmet-mounted Load-carryinG computer screens. -

MS. 129: Camp Edwards Postcard Collection

Camp Edwards Postcard Collection MS. 129 Sturgis Library Archives Town and Local History Collection Camp Edwards Postcard Collection MS. 129 Extent: 1 folder in a box with multiple collections (MS. 127-129) Scope and Content Note: The collection consists of 46 postcards showing a variety of scenes in Cape Cod’s Camp Edwards in Falmouth, Massachusetts. The images depict Camp life, buildings, training, troops, and more. Of special note is a miniature muslin mail bag with leather top which holds 8 miniature postcards. Historical Note: [The text of this note is excerpted from Wikipedia’s entry on Camp Edwards]. Camp Edwards is a United States military training installation which is located in western Barnstable County, Massachusetts. It forms the largest part of Joint Base Cape Cod, which also includes Otis Air National Guard Base and Coast Guard Air Station Cape Cod. It was named after Major General Clarence Edwards. It is home to the 3rd Battalion, 126th Aviation. In 1931 the National Guard deemed Camp Devens to be too small to meet their needs and began to look for a new training area, and two years later Cape Cod was identified as having a suitable environment to build a new camp. Camp Edwards was officially dedicated in 1938. In 1940, the U.S. Army leased Camp Edwards as a training facility as part of its mobilization strategy for World War II. The Army undertook significant construction which helped to expand Camp Edwards from a rustic military post to a small city, overflowing with new GIs. The new plan called for new capacity to house 30,000 soldiers and was completed in just four months. -

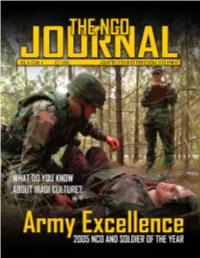

NCO Journal October 05.Pmd

VOL: 14, ISSUE: 4 OCT 2005 A QUARTERLY FORUM FOR PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT Soldiers in a Humvee search for people wishing to be rescued from Hurricane Katrina floodwaters in downtown New Orleans. Photo courtesy of www.army.mil. by Staff Sgt. Jacob N. Bailey INSIDE“ ON POINT 2-3 SMA COMMENTS IRAQI CULTURE: PRICELESS Tell the Army story with pride. They say “When in Rome, do 4-7 NEWS U CAN USE as the Romans.” But what do you know about Iraqi culture? The Army is doing its best to LEADERSHIP ensure Soldiers know how to “ manuever as better ambassa- dors in Iraq. DIVORCE: DOMESTIC ENEMY Staff Sgt. Krishna M. Gamble 18-23 National media has covered it, researchers have studied it and the sad fact is Soldiers are ON THE COVER: living it. What can you as Spc. Eric an NCO do to help? Przybylski, U.S. Dave Crozier 8-11 Army Pacific Command Soldier of the Year, evaluates NCO AND SOLDIER OF THE YEAR a casualty while he Each year the Army’s best himself is evaluated NCOs and Soldiers gather to during the 2005 NCO compete for the title. Find out and Soldier of the who the competitors are and Year competition more about the event that held at Fort Lee, Va. PHOTO BY: Dave Crozier embodies the Warrior Ethos. Sgt. Maj. Lisa Hunter 12-17 TRAINING“ ALIBIS NCO NET 24-27 LETTERS It’s not a hammer, but it can Is Detriot a terrorist haven? Is Bart fit perfectly in a leader’s Simpson a PsyOps operative? What’s toolbox. -

MVCC January 2021

MVCC 2021 APRIL 25 TO MAY 1 SPRING MEET REGISTRATION FORM ENCLOSED…!!! WEST COAST Check your membership expiration on Newsletter THE MILITARY VEHICLE COLLECTOR CALIFORNIA NEWSLETTER EDITOR: Johnny Verissimo January 2021 VOL. 6 Photo by Johnny Verissimo at the MVCC Petaluma Meet Visit our website: www.mvccnews.net & www.facebook.com/MVCCCAMPPETALUMA MVCC PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Chris Thomas, MVCC President If you’re a member and want to see the Newsletter in COLOR you can do so on (559)-871-6507 the MVCCNEWS.NET website. Simply log in and view ALL MVCC newsletters in [email protected] full color. Greetings MVCC! So as always, I hope everyone is still making it in the latest Stay-At-Home orders. The question on everyone’s mind is – Are we still having a meet? The short answer is YES. The long answer is the MVCC will work to have a safe and fun gathering for our members and guests. As I said in the last newsletter, it may not be a “swap meet” or a “club campout” but an “outdoor museum” to showcase the history of military transport. Your MVCC board is working to have every- thing in place to have a great meet at Camp Plymouth as well as contingency plans for the event or circumstances that may re- quire changes to make this happen. So, as of December 12, this is what will be the requirements for each of the following groups/activities: Campsites with no selling: In your own site you are not required to wear a mask or keep 6ft, as long as it is only your site -mates. -

Soldier Armed Body Armor Update by Scott R

Soldier Armed Body Armor Update By Scott R. Gourley In a June 2006 statement before the dier Survivability with the Office of House Armed Services Committee, Program Executive Office Soldier, the mong the most significant recent then-Maj. Gen. Stephen M. Speakes, latest system improvements inte- Adevelopments that directly in- who was director, Force Development, grated into the new improved outer crease warfighter safety and effective- Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff, G-8, tactical vest, as with earlier advances, ness are the enhancements to the pro- offered a brief chronology of the IBA reflect additional feedback from sol- tective ensemble known as Interceptor program, which highlighted the link- diers in the field. body armor (IBA). As the most up-to- age between that program’s evolution “We receive that feedback in differ- date body armor available, IBA is a and warfighter feedback. ent ways,” Myles explained. “One way, modular body armor system that con- I 1999—The Army started fielding for example, was through a soldier pro- sists of an outer vest, ballistic plates the OTV with small arms protective tection demonstration that we con- and attachments that increase the areas inserts (SAPI) to soldiers deployed in ducted in August 2006 at Fort Benning, of coverage. The system increases sol- Bosnia. Ga. We had industry provide us some dier survivability by stopping or slow- I April 2004—Theater reported 100 body armor for soldiers to evaluate. ing bullets and fragments and reducing percent fill of 201,000 sets of IBA (OTV These were soldiers that had just re- the number and severity of wounds. -

Seen at the 53Rd SDC International Meet

Seen at the 53rd SDC International Meet Left: Richard Volkmer’s 1954 Com- mander Starliner at the Studebaker National Museum. Below: meet co-chair, Bob Henning. Right: Three vehicles seen at the car show. photos by John Cosby photo by John Cosby photo by Richard Volkmer photo by Don Cuddihee Studebakers lining up ready for the parade. 6 • 53rd SDC International Meet • September 2017 • Turning Wheels photo by John Cosby Above and Below: Two of the vehicles in the car coral at the fairgrounds. Right: Awards presentation included the slideshow on the jumbotron. Lower Right: About 500 people gathered at the Palais Royale Ballroom for Members’ Night, which included dinner, Studebaker band concert, and presentations. photo by Evan Severson photo by John Cosby photo by John Cosby Turning Wheels • September 2017 • 53rd SDC International Meet • 7 Vehicle Judging at South Bend 2017 by Ed Smith Vehicle Judging at South Bend 2017 – It started out cold and wet then got … by Ed Smith his years’ International in South bend saw another return the major and minor points of the 162 vehicles presented Hawk, and other parts. I wonder if Johnny Cash had any- Thome for Studebaker. There was a good variety to see to them for scrutiny. thing to do with this one? and it is amazing just how many owners can keep up with There were convertibles where the driver had not yet Fathers, sons, friends and families gathered together to their fifty-plus-year-old vehicles. frozen at the wheel, and plenty of bullet noses that pierced show their personalities in their Studebaker creations. -

University of Maine, World War II, in Memoriam, Volume 1 (A to K)

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine General University of Maine Publications University of Maine Publications 1946 University of Maine, World War II, In Memoriam, Volume 1 (A to K) University of Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/univ_publications Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the History Commons Repository Citation University of Maine, "University of Maine, World War II, In Memoriam, Volume 1 (A to K)" (1946). General University of Maine Publications. 248. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/univ_publications/248 This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in General University of Maine Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF MAINE WORLD WAR II IN MEMORIAM DEDICATION In this book are the records of those sons of Maine who gave their lives in World War II. The stories of their lives are brief, for all of them were young. And yet, behind the dates and the names of places there shines the record of courage and sacrifice, of love, and of a devotion to duty that transcends all thought of safety or of gain or of selfish ambition. These are the names of those we love: these are the stories of those who once walked with us and sang our songs and shared our common hope. These are the faces of our loved ones and good comrades, of sons and husbands. There is no tribute equal to their sacrifice; there is no word of praise worthy of their deeds. -

Canvas Tops and Seat Cushion Sets for Historic Military Vehicles

http://www.nekvasil.cz/en 7/3/20 AUTOPLACHTY NEKVASIL canvas tops and seat cushion sets for historic military vehicles SPECIAL OFFER Canvas top for Halftrack M3A1 26,500 CZK canvas top for Halftrack M3A1 US original cargo space front/rear end curtain Dodge M37 “Korea” 2,900 CZK US original cargo space front/rear end canvas curtain for Dodge M37 “Korea” Reduction gearbox Ford GPA 23,000 CZK original reduction gearbox for Ford GPA Radiator Ford GPA 9,200 CZK original radiator for Ford GPA Saddle bag for BSA M20 of Czech canvas à 2,700 CZK canvas saddle bag for BSA M20 Military Motorcycle of US canvas à 3,400 CZK Canvas shield “MILITARY POLICE” Harley-Davidson WLA 700 CZK canvas shield “MILITARY POLICE” for Harley-Davidson WLA Carbine M1 cover “SEMS 1943” canvas cover “SEMS 1943” for United States Carbine, Caliber .30, M1 Cover for a german machine gun canvas/leather cover for a german machine gun (if you know the corresponding weapon's type, please let us know) 2,900 CZK Headlight covers for Horch 901 Kfz.15 600 CZK canvas headlight/front lamp covers for Horch 901 Kfz.15 Cover “BG-153” for radio BC 620/659 of Czech canvas 3,600 CZK canvas cover “BG-153” for U.S. radio BC 620/659 Signal Corps of US canvas 4,500 CZK US camp bed canvas 2,300 CZK canvas for folding US camp bed/cot Renovated car Jeep Willys MA 1941 Renovated car Jeep Willys MA 1941 JEEP MA|MB|GPW Canvas summer top MA of Czech canvas 6,700 CZK canvas soft top for jeep Willys MA of US canvas 8,400 CZK 1/13 http://www.nekvasil.cz/en 7/3/20 Canvas summer top MB/GPW of Czech canvas -

Kdh Defense Systems Catalogs Contract Award 12Psx0315

Kdh defense systems Catalogs Contract award 12psx0315 AMERICAN-MADE CUSTOM BODY ARMOR SOLUTIONS Military • Law Enforcement • Corrections • International REDEFINING PERFORMANCE EXCELLENCE America's cops put their lives on the line each and every day -- and that’s why the pursuit of excellence is so important to us at KDH Defense Systems. KDH is in the business of saving the lives of not only America's cops, but also its federal agents, soldiers, marines and special operations warriors. TABLE OF CONTENTS Since 2003, the mission of KDH has been to give its customers the best possible, quality armor solutions no matter what - accepting nothing less than perfection. About KDH Defense Systems, Inc. 2 First Responder Plate Carrier (FRPC) 26 The investment that KDH makes in research and development, testing and Ballistic Systems 4 KDHS 27 evaluation results in unique, innovative trend setting solutions that Law Enforcement Concealable Body Armor 6 Tactical Accessories: Pouches | ID | Blankets 28 Mobile Defense Shield ultimately become the industry standard. You have my personal guarantee Transformer Armor System 7 29 Hard Armor Plates that our products will consistently exceed your expectations. Elite 10 30 Valor 11 Helmets 33 CLK Female Concealable Vest 12 Military Body Armor 34 At KDH, we don't just design and build body armor, we redefine perfor- Sleek 14 USMC Improved Modular Tactical Vest (IMTV) mance excellence and push the limits of what's possible, ensuring that the 36 Uniform Shirt Carrier (USC) 15 USMC Plate Carrier 37 vest you wear is stronger, lighter and more comfortable - and one day, may Outer Patrol Carrier (OPC) 16 Soldier Plate Carrier System (SPCS) 38 even save your life. -

Joint Base Cape Cod Cleanup Team Building 1805 Camp Edwards, MA October 14, 2015 6:00 – 8:00 P.M

Joint Base Cape Cod Cleanup Team Building 1805 Camp Edwards, MA October 14, 2015 6:00 – 8:00 p.m. Draft Meeting Minutes Member: Organization: Telephone: E-mail: Dan DiNardo JBCC CT/Falmouth 508-547-1659 [email protected] Rose Forbes AFCEC/JBCC 508-968-4670x5613 [email protected] Ben Gregson IAGWSP 508-968-5821 [email protected] Bob Lim EPA 617-918-1392 [email protected] Charles LoGuidice JBCC CT/Falmouth 508-563-7737 [email protected] Len Pinaud MassDEP 508-946-2871 [email protected] Diane Rielinger JBCC CT/Falmouth 508-563-7533 [email protected] Bill Winters JBCC CT/Falmouth 508-548-7365 [email protected] Facilitators: Organization: Telephone: E-mail: Ellie Donovan MassDEP 508-946-2866 [email protected] Attendees: Organization: Telephone: E-mail: Lori Boghdan IAGWSP 508-968-5635 [email protected] Jen Bouchard EA 508-968-4754 [email protected] Jane Dolan EPA 617-918-1272 [email protected] Kimberly Gill Portage 774-836-2054 [email protected] Elliott Jacobs MassDEP 508-948-2786 [email protected] James Hocking Resident 508-548-5233 [email protected] Doug Karson AFCEC 508-968-4678 [email protected] Richard Kendall Falmouth Resident 508-548-9386 Elizabeth Kirkpatrick USCG 774-810-6519 [email protected] Glen Kernusky Camp Edwards 508-958-2838 [email protected] Robert Lim EPA 617-918-1392 [email protected] Gerard Martin MassDEP 508-946-2799 [email protected] Don McCarthy Resident 508-566-4783 [email protected] Mary O’Reilly CH2M 508-968-4670 [email protected] Paul Rendon JBCC 774-327-0643 [email protected] Pam Richardson IAGWSP 508-968-5630 [email protected] Nigel Tindall CH2M 508-968-4754 [email protected] Handouts Distributed at Meeting: 1. -

Ocm16270894-1966.Pdf (2.516Mb)

),,1( 3 os-. ,,.., J A ,,11\.. /9 ~ 6 " .. " , , .4 ••" • , " ,... " .) . ~ ~ ~ . ~ : :4 .. : ...... ".. .- : "' .: ......... : •• :.:: ;" -a : • .I~" ) I~ ••.••••.• : .••• ., • . •• :: ••• ! ... 3 s-s-. , 113 A ~3 /lJ 19 6 ~ ~ THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS MILITARY DIVISION THE ADJUTANT GENERAL'S OFFICE 905 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston 02215 31 December 1966 SUBJECT: Annual Report, Military Division, Commonwealth of Massachusetts TO : His Excellency John A. Volpe Governor and Commander-in-Chief State House Bo ston, Mas sachusetts I. GENERAL 1. This annual report of the Military Division of the Commonwealth for the calendar year 1966, although not required by law, is prepared for the information of the Governor and Commander-in-Chief, as well as for other public officials and t he general public. II. DESCRIPTION 2. The Military Division of the Commonwealth , organized under Chapter 33 of the General laws, comprises the entire military establishment of Massachu setts. The Gover nor is Commander -in-Chief, in accordance with Article LIV of the Amendments t o the Constitution of the Commonwealth. The Adjutan.t General is Chief of Staff to the Commander-in-Chief and exe.cutiveand administrative head of the Military Division which consists of the following: a. The State Staff. b. The Aides -de-Camp of the Commander-in-Chief. c. The Army National Guard composed of the following organizations: Hq & Hq Det MassARNG 26th Infantry Division 102d Ar t illery Group 181st Engineer Battalion 241st Engineer Battalion 109 th Signal Battalion 164th Transportation Battalion 1st Battalion (Nike-Hercu1es) 241st Artillery 101s t Ordnance Company 215 th Army Band 65 th Medical Detachment 293d Medical Detachment 31 Dec 66 SUBJECT: Annual Report, Military Division, Commonwealth of Massachusetts d. -

Report Special Recess Committee on Aviation

SENATE No. 615 Cl)t Commontoealtft of 00as$acftu$ett0 REPORT OF THE SPECIAL RECESS COMMITTEE ON AVIATION March, 1953 BOSTON WRIGHT <t POTTER PRINTING CO., LEGISLATIVE PRINTERS 32 DERNE STREET C&e Commontoealtl) of 9@assac|nioetts! REPORT OF THE SPECIAL RECESS COMMITTEE ON AVIATION. PART I. Mabch 18. 1953. To the Honorable Senate and House of Representatives. The Special Joint Committee on Aviation, consisting of members of the Committee on Aeronautics, herewith submits its report. As first established in 1951 by Senate Order No. 614, there were three members of the Senate and seven mem- bers of the House of the Committee on Aeronautics to sit during the recess for the purpose of making an investiga- tion and study relative to certain matters pertaining to aeronautics and also to consider current documents Senate, No. 4 and so much of House, No. 1232 as pertains to the continued development of Logan Airport, including constructions of certain buildings and other necessary facilities thereon, and especially the advisability of the construction of a gasoline and oil distribution system at said airport. Senate, No. 4 was a petition of Michael LoPresti, establishing a Massachusetts Aeronautics Au- thority and transferring to it the power, duties and obligations of the Massachusetts Aeronautics Commis- sion and State Airport Management Board. Members appointed under this Order were: Senators Cutler, Hedges and LoPresti; Representatives Bradley, Enright, Bryan, Gorman, Barnes, Snow and Campbell. The underground gasoline distribution system as pro- posed in 1951 by the State Airport Management Board seemed the most important matter to be studied. It was therefore voted that a subcommittee view the new in- stallation of such a system at the airport in Pittsburgh, Pa.