Documents Tendered by the 2Nd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Index No Marks Sex Med Name 2200015 041 F 2200023 040 F 2200031 047 F 2200040 049 M 2200058 046 F 2200066 028 M 2200074 042 F 22

INDEX NO MARKS SEX MED NAME ADDRESS POSTAL ADDRESS 2200015 041 F SIN WASANTHI, M.K. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, THIHAGODA. 2200023 040 F SIN KUMUDINI, E.V.S. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, THIHAGODA. 2200031 047 F SIN WICKRAMASINGHE, W.M.K.P. DIVISIONAL SECRETARY OFFICE, UKUWELA. 2200040 049 M SIN BANDULA, B.G. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, UKUWELA. 2200058 046 F SIN SAMARATHUNGE, S.M.N.R.K. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, UKUWELA. 2200066 028 M SIN ABULASIN, S. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, UKUWELA. 2200074 042 F SIN RANASINGHE, M.G.C. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, UKUWELA. 2200082 040 F SIN MALIMAGE, G.M.P.S. A.G.A. OFFICE, KOLONNAWA. 2200090 044 M SIN PREMALAL, A.A.D.K. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, KOLONNAWA. 2200104 042 F SIN GURUGE, I. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, KOLONNAWA. 2200112 037 F SIN VIOLET, V.D.R. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, KOLONNAWA. 2200120 051 F SIN BANNEHEKA, B.M.W.K. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, ANAMADUWA. 2200139 044 F SIN HERATH, I.M.N.S.K. DISTRICT SECRETARIAT, SAMURDHI OFFICE, KURUNEGALA. 2200147 053 M SIN WIJESOORIYA, K.D.G. DISTRICT SECRETARIAT, KURUNEGALA. 2200155 046 M SIN CHAMINDA, K.M.R. SAMURDHI MANAGER, DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, PASSARA. 2200163 055 F SIN HETTIGE, D.H.S.L. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, PASSARA. 2200171 066 F SIN KARUNAWATHI, J.M. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, PASSARA. 2200180 053 F SIN DUNUSINGHE, P.N. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, PASBAGE KORALE, NAWALAPITIYA. 2200198 060 F SIN SAMUDDIKA, W.P.N. DIVISIONAL SECERATARIAT, PASBAGE KORALE, NAWALAPITIYA. 2200201 042 M SIN RANAWEERA, K.S. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, PASBAGE KORALE, NAWALAPITIYA. 2200228 041 F SIN INDRASEELI, K.M.N. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, IMBULPE. 2200236 045 F SIN UDAGALADENIYA, S.M.I. -

Buddhist Forest Monasteries and Meditation Centres in Sri Lanka a Guide for Foreign Buddhist Monastics and Lay Practitioners

Buddhist Forest Monasteries and Meditation Centres in Sri Lanka A Guide for Foreign Buddhist Monastics and Lay Practitioners Updated: April 2018 by Bhikkhu Nyanatusita Introduction In Sri Lanka there are many forest hermitages and meditation centres suitable for foreign Buddhist monastics or for experienced lay Buddhists. The following information is particularly intended for foreign bhikkhus, those who aspire to become bhikkhus, and those who are experienced lay practitioners. Another guide is available for less experienced, short term visiting lay practitioners. Factors such as climate, food, noise, standards of monastic discipline (vinaya), dangerous animals and accessibility have been considered with regard the places listed in this work. The book Sacred Island by Ven. S. Dhammika—published by the BPS—gives exhaustive information regarding ancient monasteries and other sacred sites and pilgrimage places in Sri Lanka. The Amazing Lanka website describes many ancient monasteries as well as the modern (forest) monasteries located at the sites, showing the exact locations on satellite maps, and giving information on the history, directions, etc. There are many monasteries listed in this guides, but to get a general idea of of all monasteries in Sri Lanka it is enough to see a couple of monasteries connected to different traditions and in different areas of the country. There is no perfect place in samṃsāra and as long as one is not liberated from mental defilements one will sooner or later start to find fault with a monastery. There is no monastery which is perfectly quiet and where the monks are all arahants. Rather than trying to find the perfect external place, which does not exist, it is more realistic to be content with an imperfect place and learn to deal with the defilements that come up in one’s mind. -

Local Government Enhancement Sector Project (LGESP)

EA Progress Report Project Number: 42459-013 Loan 2790 Period covered: October to December 2015 SRI: Local Government Enhancement Sector Project (LGESP) Prepared by LGESP (Pura Neguma) Project Management Unit for the Ministry of Provincial Councils and Local Government, Colombo, Sri Lanka. The Executing Agency(EA)’s Progress Reports are documents owned by the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff. These documents are made publicly available in accordance with ADB’s Public Communications Policy 2011 and as agreed between ADB and the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. Government of Sri Lanka Ministry of Provincial Councils and Local Government Quarterly Progress Report Q4 – 2015 ( October - December 2015) January 2016 Local Government Enhancement Sector Project ADB Loan Number: Loan 2790-SRI Project Management Unit Local Government Enhancement Sector Project 191 A, J R Jayawardene Centre, Dharmapala Mawatha, Colombo 07, Sri Lanka Ministry of Provincial Councils and Local Government Contents Contents Executive Summary I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 5 A. Background .................................................................................................... 5 B. Scope of the Project ....................................................................................... 5 II. PROJECT PROGRESS .............................................................................................. -

10. Kaluthara

Definition for Home Garden1 1. A piece of land which has a dwelling house and some form of cultivation can be considered as a home garden if the total area of the piece of land is twenty or less than twenty perches. 2. A piece of land which has a dwelling house and some form of cultivation, if total land areas is more than twenty perches can also be considered as a home garden if following two conditions are satisfied. a. It is mainly meant for residential purposes. b. A produce of cultivated land in the home garden is largely for home consumption. Examples for Home Garden a) A land of extent 20 perches or less has a dwelling house and a few bearing coconut trees. b) A land of 20 perches or less, has a dwelling house and having extensive cultivation mainly for commercial purposes By definition (1) this land can be considered as a home garden c) A two acre land has dwelling house. Although the extent covered by a house is comparatively small and few crops are grown mainly for home consumption. According to definition (2) this land is also a home garden. d) A small house in a two roods land. But the usable land has been intensively cultivated with vegetable crops which are mainly for sale. Although this land has a dwelling house and also extent is small, as the produce from the land is not mainly for home consumption, it will not be treated as a home garden. However, in this survey cases like (d) have been treated as a home garden by excluding the area under commercial cultivation. -

MOH Area Code

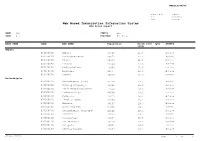

WEBIIS/AM/04 Generated By madzper Date 03/03/2016 Time 09:07 AM Web Based Immunization Information System MOH Areas Report NAME All STATUS ALL CODE All PROVINCE All Areas RDHS NAME CODE MOH NAME Population Birth rate (per STATUS 1000) Ampara 050160010 Ampara 45513 22.6 Active 050160020 Dehiattakandiya 62073 22.6 Active 050160030 Uhana 60666 22.6 Active 050160040 Mahaoya 21564 22.6 Active 050160050 Padiyathalawa 18956 22.6 Active 050160060 Lahugala 9265 22.6 Active 050160070 Damana 40067 22.6 Active Anuradhapura 070200010 Anuradhapura (cnp) 86299 19.3 Active 070200020 Kahatagasdigiliya 41825 19.3 Active 070200030 Kekirawa(palugaswewa) 77044 19.3 Active 070200040 Medawachchiya 48569 19.3 Active 070200050 Padaviya 23822 19.3 Active 070200060 Thambuttegama 43650 19.3 Active 070200070 Galnewa 36107 19.3 Active 070200080 Nochchiyagama 51678 19.3 Active 070200090 Anuradhapura (nnp/npe) 94202 19.3 Active 070200100 Mihintale 36516 19.3 Active 070200110 Rajanganaya 34637 19.3 Active 070200120 Horowpathana 38234 19.3 Active 070200130 Palagala 35031 19.3 Active 070200140 Kebethigollewa 23087 19.3 Active MOH Areas Report Page 1 of 13 WEBIIS/AM/04 RDHS NAME CODE MOH NAME Population Birth rate (per STATUS 1000) Anuradhapura 070200150 Galenbindunuwewa 48368 19.3 Active 070200160 Ipalogama 40142 19.3 Active 070200170 Thalawa 59930 19.3 Active 070200180 Thirappane 32063 19.3 Active 070200190 Rambewa 38233 19.3 Active Badulla 080220010 Badulla 77357 18.7 Active 080220020 Bandarawela 67396 18.7 Active 080220030 Girandurukotte 37586 18.7 Active 080220040 -

Efficiency Bar Examination for Officers in Class Ii of Pmas - 2010(Ii)

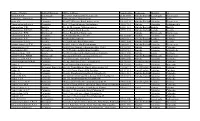

EFFICIENCY BAR EXAMINATION FOR OFFICERS IN CLASS II OF PMAS - 2010(II) INDNO NAME ADDRESS POSTAL M001 M002 10000013 UMAH K. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT,VILISOUTH WEST, SANDILIPAY --- 044 10000030 JAYASENA G.S SECRERARY ,MINISTRY OF BUDDASASANA & RELIGIOUS AFFAIRS, COLOMBO 07. --- 031 10000058 SRIYALATHA P.M ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF AGRICULTURE OFFICE, HUNGAMA. 044 --- 10000092 PUSHPANJALI K.N HELAWATTHA,ALIGABEDDA, BADULLA. 060 032 10000135 NALINI N. REGIONAL DIRECTORS' OFFICE TRINCOMALEE. --- 041 10000152 PERERA H.A.A MINISTRY OF EDUCATON, 2ND FLOOR, ISURUPAYA, BATTARAMULLA. --- 020 40000010 PREMALAL, K.T.S. MEDICAL SUPPLIES DIVISION, 357, DEANS ROAD, COLOMBO 10. --- 057 40000024 RATHNAYAKA, U.S. MEDICAL SUPPLIES DIVISION,357,BADDEGAMA WIMALAWANSA HIMI MW. COLOMBO 10. 00+ 00+ 40000038 PERERA, M.S.R. MEDICAL SUPPLIES DIVISION,357,BADDEGAMA WIMALAWANSA HIMI MW. COLOMBO 10. --- 043 40000041 BANDUSENA, K.D.G.M. MEDICAL SUPPLIES DIVISION, 357, DEANS ROAD, COLOMBO 10. 00+ 00+ 40000055 GUNASEKERA, D.L. MEDICAL SUPPLIES DIVISION, 357, DEANS ROAD, COLOMBO 10. --- 00+ 40000069 PATHMASIRI, E.G.J. NATIONAL DRUGS QUALITY,ASSURANCE LAB, 120, NORRIS CANAL RD., COLOMBO 10. 00+ 00+ 40000072 LIYANAGE, N.M.U. M/Y OF HEALTH, SUWASIRIPAYA, N.T.A. BRANCH, COLOMBO 10. 00+ 00+ 40000086 RATHNAKANTHI, R.A.A. BASE HOSPITAL, MULLERIYAWA. --- 037 40000090 ALGAMA, W.V. 62/2, GAMAMEDA ROAD, MATHAMMANA, MINUWANGODA. 00+ 00+ 40000101 FERNANDO, L.B. 231, FAMILY HEALTH BUREAU, DE SERAM PLACE, COLOMBO 10. --- 020 40000115 SOMALATHA, M.K.S. 231, FAMILY HEALTH BUREAU, DE SERAM PLACE, COLOMBO 10. 054 027 40000129 KARUNAWATHI, S.G. 154/4, ARTIGALA ROAD, HANWELLA. 00+ 00+ 40000132 FONSEKA, H.S. DE SOYSA MATERNITY HOSPITAL, COLOMBO 8. -

Western Province

Initial Environmental Examination June 2017 SRI: Second Integrated Road Investment Program Western Province Prepared by Road Development Authority, Ministry of Higher Education and Highways for the Government of Sri Lanka and the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 30 May 2017) Currency unit – Sri Lanka Rupee (SLRl} SLR1.00 = $ 0.00655 $1.00 = Rs 152.63 ABBREVIATIONS ABC - Aggregate Base Course AC - Asphalt Concrete ADB - Asian Development Bank CBO - Community Based Organizations CEA - Central Environmental Authority DoF - Department of Forest DOI - Department of Irrigation DSDs - Divisional Secretary Divisions DOFC - Department of Forest Conservation DWLC - Department of Wild Life Conservation EC - Environmental Checklist EIA - Environmental Impact Assessment EMP - Environmental Management Plan EPL - Environmental Protection License ESDD - Environmental and Social Development Division FBO - Farmer Based Organizations GND - Grama Niladhari Divisions GoSL - Government of Sri Lanka GRC - Grievance Redress Committee GRM - Grievance Redress Mechanism GSMB - Geological Survey and Mines Bureau IEE - Initial Environmental Examination iRoad - Integrated Road Investment Program iRoad 2 - Second Integrated Road Investment Program LA - Local Authority LAA - Land Acquisition Act MC - Municipal Council MER - Manage Elephant Range MOHPS - Ministry of Highways, Ports and Shipping NAAQS - National Ambient Air Quality Standards NBRO - National Building Research Organization NEA - National Environmental Act NWS&DB - National Water Supply and Drainage Board PCPIU - Project Coordination Project Implementing Unit PIC - Project Implementation Consultant PIU - Project Implementation Unit PRDA - Provincial Road Development Authority PS - Pradeshiya Sabha RDA - Road Development Authority ROW - Right of Way TOR - Terms of Reference TEEMP - Transport Emissions Evaluation Model for Projects UNEP - United Nations Environment Program This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. -

Name of Notary Judical Division Office Address Appoin Date Language District Lr Aalas T.F.S.S

Name of Notary Judical Division Office Address Appoin date Language District Lr Aalas T.F.S.S. Kurunegala No.185/2 , Puttalam Rd, Kurunegala 21.08.1980 Sinhala/English Kurunegala Kurunegala Aapa N.H. (Nadeesha) Galle "Priya Madura",Nagoda,Galle. 2014.05.21 English Galle Galle Aapa S.N. Colombo No.447/3,Kottawa Road,Athurugiriya. 2014.05.30 Sinhala/English Colombo Homagama Abayagunawardhana S. Gampaha No:115,Horagollawatta,Nittambuwa. 1985.07.10 Sinhala Gampaha Aththanagalla Abayarathna Y.B. Badulla No. 46, Dehigama, Mahiyanganaya. 2003.11.21 Sinhala/English Badulla Badulla Abayarathne D.R.N.D. Kegalle No.26,Courts Road,Kegalle 1997.11.20 Sinhala/English Kegalle Kegalle Abayarathne H.M. Kurunegala No.62, Kandy Rd, Kurunegala - Sinhala Kurunegala Kurunegala Abayarathne K.S.R. Colombo No.83,Rosmid Place,Col 07 2013.03.08 English Colombo Colombo Abayarathne N.P Kalutara Mankada,Bombuwala 2005.05.11 Sinhala/English Kalutara Kalutara Abayarathne S.D.B. Kegalle No.76/4,Kandy Road,Mawanella 1989.11.09 Sinhala/English Kegalle Kegalle Abayasiriwardena P.N. Colombo No.453, Suhada Mw.Kahathuduwa 2000.04.12 Sinhala/English Colombo Homagama Abayasundara Y.H. Colombo No.62/2,Sri Darmakeerthiyarama Mw.,Col03 2012.04.18 Sinhala Colombo Colombo Abayathilaka K.I Avissawella No 78 Thilaka, Arukwaththa Padukka 2009.09.11 Sinhala Colombo Avissawella Abayawardena H.W. Kandy No.09,Angamawaththa,Bothalapitiya,Gampola. 2004.11.01 Sinhala Kandy Gampola Abayawardene H.N.B. Kurunegala Kongaslandawaththa,Aragama,Gokarella 2011.08.08 Sinhala/English Kurunegala Kurunegala Abayaweera D.N.S.S. Gampaha No.186,Kossinna,Ganemulla 2009.02.02 Sinhala Gampaha Gampaha Abayawickkrama M.R.H Colombo No. -

Annual Performance Report and Accounts of the District Secretariat

ANNUAL PERPORMANCE REPORT & ACCOUNTS - 2018 KALUTARA DISTRICT Page 1 ANNUAL PERPORMANCE REPORT & ACCOUNTS - 2018 KALUTARA DISTRICT Content 1. Message of the Government Agent / District Secretary .......................................................................... 5 2. Introduction of Kalutara District Secretariat ........................................................................................... 6 2.1 Vision and Mission Statement........................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Objectives and Values of the District Secretariat .............................................................................. 7 2.3 Activities and Progress of the District Secretariat ............................................................................. 8 3. Introduction of the District ...................................................................................................................... 9 3.1. District Boundaries ........................................................................................................................ 10 3.2. Historical Background of Kalutara District .................................................................................... 10 3.3. Land Usage of Kalutara District ..................................................................................................... 10 3.4. Land Usage Pattern of the District ................................................................................................. 11 3.5. Monthly -

Joint Alternative Report of Sri Lankan NGO Collective

JOINT ALTERNATIVE REPORT From the Sri Lankan NGO Collective to the Committee Against Torture 13th October 2016 1 ABBREVIATIONS AG - Attorney General CAT - Convention Against Torture GoSL - Government of Sri Lanka HC - High Court ICRC - International Committee of the Red Cross IDP - Internally Displaced Persons IGP - Inspector General of Police JMO - Judicial Medical Officer JSC - Judicial Service Commission LLRC - Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission MC - Magistrate Court NHRC - National Human Rights Commission NGO - Non Governmental Organization OIC - Officer in Charge PTA - Prevention of Terrorism Act SC - Supreme Court UN - United Nations HRCSL - Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka 2 Table of Contents ABBREVIATIONS 2 1. INTRODUCTION 4 2. CONTEXT 4 3. DEFINITION OF TORTURE (ARTICLES 1 AND 4) 5 4. WIDESPREAD USE OF TORTURE AND ILL-TREATMENT 6 DEPLOYMENT OF MILITARY AGAINST CIVILIANS 7 MASS GRAVE INVESTIGATIONS 8 5. LACK OF LEGAL SAFEGUARDS, LEGISLATIVE, ADMINISTRATIVE, JUDICIAL OR OTHER MEASURES TO PREVENT ACTS OF TORTURE 9 ANTI-TERRORISM LAWS 9 JURISDICTION OF THE SUPREME COURT 10 WITNESS AND VICTIM PROTECTION 10 JUDICIAL SUPERVISION OF DETAINEES AND VICTIMS 11 ROLE OF JUDICIAL MEDICAL OFFICERS 12 CONDITIONS IN PRISONS AND DETENTION 13 ACCESS TO LEGAL COUNSEL 15 THE OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL 16 INVESTIGATIONS OF DEATHS IN CUSTODY 17 6. ENFORCED DISAPPEARANCES 17 7. VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN, INCLUDING SEXUAL VIOLENCE 18 8. EDUCATION AND INFORMATION REGARDING PROHIBITION OF TORTURE (ARTICLES 10) 19 9. COMPENSATION TO AND REHABILITATION FOR VICTIMS OF TORTURE (ARTICLE 14) 20 10. OVERALL OBSERVATIONS ON THE STATE PARTY REPORT 21 DESCRIPTION OF ORGANIZATIONS INVOLVED IN COMPILING THIS REPORT 23 LIST OF OF ANNEXURES 27 3 1. -

Abstract-Book-For-WESTERN PROVINCE RESEARCH SYMPOSIUM

BOOK OF ABSTRACTS OF THE WESTRN PROVINCE RESERCH SYMPOSIUM NOVEMBER 2018 ISBN – 978 – 955 – 3445 - 001 Editorial Board : Dr.Anil Samaranayake, Dr. Monika Wijerathna, Dr.Priyanga Ranasinghe, Dr.Nimali Wellapuli, Dr. Ravi Wicramaratne, Dr.Kamal Seneviratne, Dr.Jayathri Wijayarathne, Dr. Mega Ganewatta, Dr,Pamod Amarakoon, Dr.Muditha Nirmana Gunawrdana Cover design : Dr. Muditha Nirmana Gunawardana Dr.Janaka Wickramarathne Table of Contents Contents Page number Messages of Provincial Director of Health Services 01 Panel of Reviewers 03 Abstracts 05 1. KNOWLEDGE AND PREPAREDNESS ASSOCIATED WITH HOME ACCIDENTS AMONG 06 MOTHERS OF PRESCHOOL CHILDREN IN MEDICAL OFFICER OF HEALTH AREA MAHARAGAMA Weerasekera NN1, De Silva A2, Gamage D3 2.KNOWLEDGE, USE AND ATTITUDES OF NON-BIODEGRADABLE POLYTHENE AND 07 BIODEGRADABLE SUBSTITUTES AMONG FEMALE RESIDENTS IN MOH AREA, NUGEGODA Seneirathne CMGT1, Senevirathne DY1, Shahana MMF1 3.ASSESSING KNOWLEDGE, ATTITUDES AND USAGE PATTERNS OF SKIN LIGHTENING 08 PRODUCTS AMONG FEMALE TRAINEES OF NATIONAL VOCATIONAL TRAINING INSTITUTE, COLOMBO Senevirathne LPUS1, Siriwardhana PKIS1,Southirri J1 4.ASSOCIATION BETWEEN GLYCEMIC CONTROL AND TASTE PERCEPTION FOR SUCROSE IN 09 PATIENTS WITH TYPE 2 DIABETES MELLITUS Vidanage D1, Wasalathanthri S2, Hettiarachchi P3, Prathapan S4 5.EVALUATION OF THE ORAL HEALTH CARE PROGRAMME DURING PREGNANCY IN REDUCING 10 DENTAL CARIES IN YOUNG CHILDREN IN THE DISTRICT OF GAMPAHA, IN SRI LANKA Ranasinghe N1, Usgodaarachchi US2, Kanthi RDFC3 6.PREVALENCE, SEVERITY AND EXTENT OF CHRONIC PERIODONTITIS AMONG 30-60 YEAR OLD 11 ADULTS IN COLOMBO DISTRICT, SRI LANKA Wellappuli NC1, Ekanayake2 7.ORAL HEALTHCARE DURING PREGNANCY: SUSTENANCE OF CARE AND IMPLICATIONS FOR 12 FUTURE PRACTICE Ranasinghe N1,.Usgodaarachchi US 2, Kanthi RDFC3 8.ASSESSMENT OF THE LEVEL OF PUBLIC AWARENESS OF ORAL CANCER 13 SajeewaLakmini MG1, Amarainghe, AAHK2, Thubellagen DS.3, Thubellage. -

Rubber Research Institute of Sri Lanka Dartonfield, Agalawatta Vision Mission Objectives Policies

Rubber Research Institute of Sri Lanka Dartonfield, Agalawatta Vision The Institute’s vision is to emerge as the centre of excellence in providing high quality scientific technologies to the rubber industry. Mission The Institute’s mission is to revitalize the rubber sector by developing economically and environmentally sustainable innovations and transferring the latest technologies to the stakeholders through training and advisory services. Objectives Increase productivity to international standards Increase national production of NR to meet the increasing demand Optimal and sustainable utilization of land, labour and other resources Maximize domestic value addition to rubber Encourage individual competency and self development of RRI personnel and in the process, improve the organizational effectiveness of the institute Policies Continuation of the research and extension activities on all aspects of rubber production and processing Continue to promote environmentally friendly and sustainable agricultural industry Transfer the developed technologies through training and advisory services RUBBER RESEARCH BOARD ANNUAL REPORT - 2015 Contents Report by the Chairman 1 Progress Report by the Director 3 Organizational Structure 8 Major Achievements during - 2015 9 Activities of research departments during - 2015 13 Awards 27 Boards of Management and the Staff 29 List of Publications 47 Financial statements and appropriate Accounts - 2015 55 Auditor General’s Report 109 Report of the Chairman Rubber Research Board With the changes of Government and associated changes of the Ministerial portfolio, the Chairmanship and the members of the Rubber Research Board (RRB) were changed in two occasions. Hence, RRB functioned under the guidance of three Chairmen during 2015. As the third Chairman of the year, my tenure began with effect from 15th October, 2015.