BEIJING TURNS the SCREWS Freedom of Expression in Hong Kong Under Attack

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Immigration Coverage in Chinese-Language Newspapers Acknowledgments This Report Was Made Possible in Part by a Grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York

Building the National Will to Expand Opportunity in America Media Content Analysis: Immigration Coverage in Chinese-Language Newspapers Acknowledgments This report was made possible in part by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York. Project support from Unbound Philanthropy and the Four Freedoms Fund at Public Interest Projects, Inc. (PIP) also helped support this research and collateral communications materials. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors. The research and writing of this report was performed by New America Media, under the direction of Jun Wang and Rong Xiaoqing. Further contributions were made by The Opportunity Agenda. Ed - iting was done by Laura Morris, with layout and design by Element Group, New York. About The Opportunity Agenda The Opportunity Agenda was founded in 2004 with the mission of building the national will to expand opportunity in America. Focused on moving hearts, minds and policy over time, the organization works closely with social justice organizations, leaders, and movements to advocate for solutions that expand opportunity for everyone. Through active partnerships, The Opportunity Agenda uses communications and media to understand and influence public opinion; synthesizes and translates research on barriers to opportunity and promising solutions; and identifies and advocates for policies that improve people’s lives. To learn more about The Opportunity Agenda, go to our website at www.opportunityagenda.org. The Opportunity Agenda is a project of the Tides Center. Table of Contents Foreword 3 1. Major Findings 4 2. Research Methodology 4 3. Article Classification 5 4. A Closer Look at the Coverage 7 5. -

Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016

Journal of US-China Public Administration, August 2016, Vol. 13, No. 8, 499-517 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2016.08.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016 Chung Fun Steven Hung The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong After direct elections were instituted in Hong Kong, politicization inevitably followed democratization. This paper intends to evaluate how political parties’ politics happened in Hong Kong’s recent history. The research was conducted through historical comparative analysis, with the context of Hong Kong during the sovereignty transition and the interim period of democratization being crucial. For the implementation of “one country, two systems”, political democratization was hindered and distinct political scenarios of Hong Kong’s transformation were made. The democratic forces had no alternative but to seek more radicalized politics, which caused a decisive fragmentation of the local political parties where the establishment camp was inevitable and the democratic blocs were split into many more small groups individually. It is harmful. It is not conducive to unity and for the common interests of the publics. This paper explores and evaluates the political history of Hong Kong and the ways in which the limited democratization hinders the progress of Hong Kong’s transformation. Keywords: election politics, historical comparative, ruling, democratization The democratizing element of the Hong Kong political system was bounded within the Legislative Council under the principle of the separation of powers of the three governing branches, Executive, Legislative, and Judicial. Popular elections for the Hong Kong legislature were introduced and implemented for 25 years (1991-2016) and there were eight terms of general elections for the Legislative Council. -

Official Record of Proceedings

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL — 30 November 1994 1117 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 30 November 1994 The Council met at half-past Two o'clock PRESENT THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JOHN JOSEPH SWAINE, C.B.E., LL.D., Q.C., J.P. THE CHIEF SECRETARY THE HONOURABLE MICHAEL LEUNG MAN-KIN, C.B.E., J.P. THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY THE HONOURABLE SIR NATHANIEL WILLIAM HAMISH MACLEOD, K.B.E., J.P. THE ATTORNEY GENERAL THE HONOURABLE JEREMY FELL MATHEWS, C.M.G., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALLEN LEE PENG-FEI, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARTIN LEE CHU-MING, Q.C., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, O.B.E., LL.D., J.P. THE HONOURABLE NGAI SHIU-KIT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE PANG CHUN-HOI, M.B.E. THE HONOURABLE SZETO WAH THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE ANDREW WONG WANG-FAT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EDWARD HO SING-TIN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FONALD JOSEPH ARCULLI, O.B.E., J.P. 1118 HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL — 30 November 1994 THE HONOURABLE MRS PEGGY LAM, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WAH-SUM, O.B.E., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LEONG CHE-HUNG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES DAVID McGREGOR, O.B.E., I.S.O., J.P. -

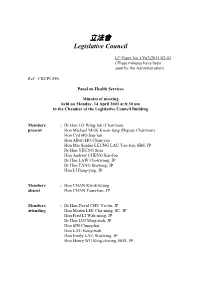

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2)2011/02-03 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Ref : CB2/PL/HS Panel on Health Services Minutes of meeting held on Monday, 14 April 2003 at 8:30 am in the Chamber of the Legislative Council Building Members : Dr Hon LO Wing-lok (Chairman) present Hon Michael MAK Kwok-fung (Deputy Chairman) Hon Cyd HO Sau-lan Hon Albert HO Chun-yan Hon Mrs Sophie LEUNG LAU Yau-fun, SBS, JP Dr Hon YEUNG Sum Hon Andrew CHENG Kar-foo Dr Hon LAW Chi-kwong, JP Dr Hon TANG Siu-tong, JP Hon LI Fung-ying, JP Members : Hon CHAN Kwok-keung absent Hon CHAN Yuen-han, JP Members : Dr Hon David CHU Yu-lin, JP attending Hon Martin LEE Chu-ming, SC, JP Hon Fred LI Wah-ming, JP Dr Hon LUI Ming-wah, JP Hon SIN Chung-kai Hon LAU Kong-wah Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon Henry WU King-cheong, BBS, JP - 2 - Public Officers : Mr Thomas YIU, JP attending Deputy Secretary for Health, Welfare and Food Mr Nicholas CHAN Assistant Secretary for Health, Welfare and Food Dr P Y LAM, JP Deputy Director of Health Dr W M KO, JP Director (Professional Services & Public Affairs) Hospital Authority Dr Thomas TSANG Consultant Clerk in : Ms Doris CHAN attendance Chief Assistant Secretary (2) 4 Staff in : Ms Joanne MAK attendance Senior Assistant Secretary (2) 2 I. Confirmation of minutes (LC Paper No. CB(2)1735/02-03) The minutes of the regular meeting on 10 March 2003 were confirmed. -

I Am Sorry. Would Members Please Deal with One Piece of Business. It Is Now Eight O’Clock and Under Standing Order 8(2) This Council Should Now Adjourn

4920 HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 29 June 1994 8.00 pm PRESIDENT: I am sorry. Would Members please deal with one piece of business. It is now eight o’clock and under Standing Order 8(2) this Council should now adjourn. ATTORNEY GENERAL: Mr President, with your consent, I move that Standing Order 8(2) should be suspended so as to allow the Council’s business this evening to be concluded. Question proposed, put and agreed to. Council went into Committee. CHAIRMAN: Council is now in Committee and is suspended until 15 minutes to nine o’clock. 8.56 pm CHAIRMAN: Committee will now resume. MR MARTIN LEE (in Cantonese): Mr Chairman, thank you for adjourning the debate on my motion so that Members could have a supper break. I hope I can secure a greater chance of success if they listen to my speech after dining. Mr Chairman, on behalf of the United Democrats of Hong Kong (UDHK), I move the amendments to clause 22 except item 12 of schedule 2. The amendments have already been set out under my name in the paper circulated to Members. Mr Chairman, before I make my speech, I would like to raise a point concerning Mr Jimmy McGREGOR because he was quite upset when he heard my previous speech. He hoped that I could clarify one point. In fact, I did not mean that all the people in the commercial sector had not supported democracy. If all the voters in the commercial sector had not supported democracy, Mr Jimmy McGREGOR would not have been returned in the 1988 and 1991 elections. -

The Basic Law and Democratization in Hong Kong

THE BASIC LAW AND DEMOCRATIZATION IN HONG KONG Michael C. Davis† I. Introduction Hong Kong’s status as a Special Administrative Region of China has placed it on the foreign policy radar of most countries having relations with China and interests in Asia. This interest in Hong Kong has encouraged considerable inter- est in Hong Kong’s founding documents and their interpretation. Hong Kong’s constitution, the Hong Kong Basic Law (“Basic Law”), has sparked a number of debates over democratization and its pace. It is generally understood that greater democratization will mean greater autonomy and vice versa, less democracy means more control by Beijing. For this reason there is considerable interest in the politics of interpreting Hong Kong’s Basic Law across the political spectrum in Hong Kong, in Beijing and in many foreign capitals. This interest is en- couraged by appreciation of the fundamental role democratization plays in con- stitutionalism in any society. The dynamic interactions of local politics and Beijing and foreign interests produce the politics of constitutionalism in Hong Kong. Understanding the Hong Kong political reform debate is therefore impor- tant to understanding the emerging status of both Hong Kong and China. This paper considers the politics of constitutional interpretation in Hong Kong and its relationship to developing democracy and sustaining Hong Kong’s highly re- garded rule of law. The high level of popular support for democratic reform in Hong Kong is a central feature of the challenge Hong Kong poses for China. Popular Hong Kong values on democracy and human rights have challenged the often undemocratic stance of the Beijing government and its supporters. -

The Portrayal of Female Officials in Hong Kong Newspapers

Constructing perfect women: the portrayal of female officials in Hong Kong newspapers Francis L.F. Lee CITY UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG, HONG KONG On 28 February 2000, the Hong Kong government announced its newest round of reshuffling and promotion of top-level officials. The next day, Apple Daily, one of the most popular Chinese newspapers in Hong Kong, headlined their full front-page coverage: ‘Eight Beauties Obtain Power in Newest Top Official Reshuffling: One-third Females in Leadership, Rarely Seen Internationally’.1 On 17 April, the Daily cited a report by regional magazine Asiaweek which claimed that ‘Hong Kong’s number of female top officials [is the] highest in the world’. The article states that: ‘Though Hong Kong does not have policies privileging women, opportunities for women are not worse than those for men.’ Using the prominence of female officials as evidence for gender equality is common in public discourse in Hong Kong. To give another instance, Sophie Leung, Chair of the government’s Commission for Women’s Affairs, said in an interview that women in Hong Kong have space for development, and she was quoted: ‘You see, Hong Kong female officials are so powerful!’ (Ming Pao, 5 February 2001). This article attempts to examine news discourses about female officials in Hong Kong. Undoubtedly, the discourses are complicated and not completely coherent. Just from the examples mentioned, one could see that the media embrace the relatively high ratio of female officials as a sign of social progress. But one may also question the validity of treating the ratio of female officials as representative of the situation of gender (in)equality in the society. -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (Ii): the Battle Over "The People" and the Business Community in the Transition to Chinese Rule

HONG KONG'S ENDGAME AND THE RULE OF LAW (II): THE BATTLE OVER "THE PEOPLE" AND THE BUSINESS COMMUNITY IN THE TRANSITION TO CHINESE RULE JACQUES DELISLE* & KEVIN P. LANE- 1. INTRODUCTION Transitional Hong Kong's endgame formally came to a close with the territory's reversion to Chinese rule on July 1, 1997. How- ever, a legal and institutional order and a "rule of law" for Chi- nese-ruled Hong Kong remain works in progress. They will surely bear the mark of the conflicts that dominated the final years pre- ceding Hong Kong's legal transition from British colony to Chinese Special Administrative Region ("S.A.R."). Those endgame conflicts reflected a struggle among adherents to rival conceptions of a rule of law and a set of laws and institutions that would be adequate and acceptable for Hong Kong. They unfolded in large part through battles over the attitudes and allegiance of "the Hong Kong people" and Hong Kong's business community. Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule ("Endgame I") focused on the first aspect of this story. It examined the political struggle among members of two coherent, but not monolithic, camps, each bound together by a distinct vision of law and sover- t Special Series Reprint: Originally printed in 18 U. Pa. J. Int'l Econ. L. 811 (1997). Assistant Professor, University of Pennsylvania Law School. This Article is the second part of a two-part series. The first part appeared as Hong Kong's End- game and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule, 18 U. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

Digital News Report 2018 Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2018 2 2 / 3

1 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018 Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2018 2 2 / 3 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, David A. L. Levy and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2018 4 Contents Foreword by David A. L. Levy 5 3.12 Hungary 84 Methodology 6 3.13 Ireland 86 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.14 Italy 88 3.15 Netherlands 90 SECTION 1 3.16 Norway 92 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 8 3.17 Poland 94 3.18 Portugal 96 SECTION 2 3.19 Romania 98 Further Analysis and International Comparison 32 3.20 Slovakia 100 2.1 The Impact of Greater News Literacy 34 3.21 Spain 102 2.2 Misinformation and Disinformation Unpacked 38 3.22 Sweden 104 2.3 Which Brands do we Trust and Why? 42 3.23 Switzerland 106 2.4 Who Uses Alternative and Partisan News Brands? 45 3.24 Turkey 108 2.5 Donations & Crowdfunding: an Emerging Opportunity? 49 Americas 2.6 The Rise of Messaging Apps for News 52 3.25 United States 112 2.7 Podcasts and New Audio Strategies 55 3.26 Argentina 114 3.27 Brazil 116 SECTION 3 3.28 Canada 118 Analysis by Country 58 3.29 Chile 120 Europe 3.30 Mexico 122 3.01 United Kingdom 62 Asia Pacific 3.02 Austria 64 3.31 Australia 126 3.03 Belgium 66 3.32 Hong Kong 128 3.04 Bulgaria 68 3.33 Japan 130 3.05 Croatia 70 3.34 Malaysia 132 3.06 Czech Republic 72 3.35 Singapore 134 3.07 Denmark 74 3.36 South Korea 136 3.08 Finland 76 3.37 Taiwan 138 3.09 France 78 3.10 Germany 80 SECTION 4 3.11 Greece 82 Postscript and Further Reading 140 4 / 5 Foreword Dr David A. -

Monthly Report HK

January 2011 in Hong Kong 31.1.2011 / No 85 A condensed press review prepared by the Consulate General of Switzerland in HK Economy + Finance HK still ranked world's freest economy: HK remains the world’s freest economy for the 17th straight year and ranked 1st out of 41 countries – according to a report released by the Heritage Foundation and the Wall Street Journal. The city’s score remains unchanged from last year at 89.7 out of 100 in the 2011 Index of Economic Freedom, with small declines in the score for government spending and labour freedom offsetting improvements in fiscal freedom, monetary freedom, and freedom from corruption. The report said HK is one of the world’s most competitive financial and business centres, demonstrating a high degree of resilience during the global financial crisis. City casts off shadow of global financial crisis: HK's economy is rebounding from the aftermath of the global financial crisis, with the public coffers enjoying the first eight-month surplus in three years. The latest announcement showed a far better financial picture than the government had forecast. In his budget speech in February, Financial Secretary John Tsang projected a net deficit of HK$25.2 billion for the current financial year. However, consensus estimates among most accounting firms now put the full financial year budget at a surplus of at least HK$60 billion. The reserves stood at HK$537 billion as of November 30, compared to HK$455.5 billion a year earlier. HK jobless rate falls to 4pc: HK's unemployment rate declined from 4.1 per cent in September to November last year to 4.0 per cent in October to December last year.