17-01-23 Afsi Comments.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

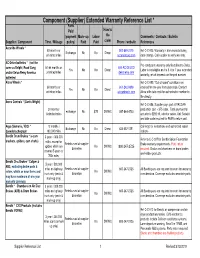

Component (Supplier) Extended Warranty Reference List *

Component (Supplier) Extended Warranty Reference List * Parts Paid How to (payment Mark- up Labor file Comments / Contacts / Bulletin Supplier / Component Time / Mileage policy) Paid Paid claim Phone / website References Accuride Wheels * 60 months or 800-869-2275 Ref C-C-005. Warranty is from manufacturing Exchange No No Direct unlimited miles accuridecorp.com date (stamp). Call supplier to verify warranty. AC-Delco batteries * (not the Pro-rated parts warranty only filed direct to Delco. same as Delphi, Road Gang 60-84 months or 800-AC-DELCO Yes No No Direct Labor is not eligible on the 5, 6 or 7 year extended and/or Delco Remy America unlimited miles delcoremy.com warranty, which depends on the part number. batteries) Alcoa Wheels * Ref C-C-099. "Out of round" conditions are 60 months or 800-242-9898 covered for one year from date code. Contact Yes No No Direct unlimited miles alcoawheels.com Alcoa with date code for authorization number to file directly. Arens Controls * (Curtis Wright) Ref C-C-056. Supplier pays part at PACCAR 24 months/ production cost + $75 labor. Total payment for exchange No $75 DWWC 847-844-4703 Unlimited miles actuator is $292.19, selector varies. Unit Serial # and date code required for RMA to return part. Argo (Siemen's, VDO) * 12 months / Call Argo for instructions and authorized repair Exchange No No Direct 425-557-1391 Speedo/tachograph 100,000 miles stations. Bendix Drum Brakes * (s-cam 3 years / 300,000 Refer to C-C-007 for Bendix Spicer Foundation brackets, spiders, cam shafts) miles, except for Reimbursed at supplier Brake warranty requirements. -

T'fj ·Laifit .-Of:Thfn~Le~ -•Fqtllpt:\C&-- ·

., ..... ~\. ,. j NRL.Bc'ActtnmRiffl?DifedprlsSt1e$·,·__ s.f ry. Is:-- O.ff -to ' t'fJ ·laifit_.-of:tHfn~le~ -•fqtllpt:\C&-- ·. r'"··' -~ .. '· . 1 . - ·I ,, 01,~,: 1?~cembe:r: 2s: 1956 Roy G ;:-Hof~nia~n:, {i.cting re·gional ,, Somebo<ty QI1Ctf ~aid, ''the 9nl'y thing YOll 'ca.11 be sure of is change," and that 1'emark <i11Jr~eto~: of ~he 20th_ J:~gi~n ?f.tlrn ,:~at.i~.~al T.~b?r. Relati_ons J certainly applies, t& _the ,Calif. ~:Nev.-Utah Weather situation arid construction industry as \ve ~:oafd m -~an Fr~nqs~o; 1ss!1ed a comp}a.1nt ~gamst HensleJ' I i)1ov'e,. Jnto t0.g·new yea.1~ of 1957. · J&qmpment Co.; Inc. and: .Hensley Thietal ;I'rr.atin~ Co., Inc., an I If ,ve·_ sa;f it'i~ )lry- on·e of . the 1 --- ----- -"·--·-- ·- ·--·--·--- p!ffiliated company, lJpoii qharges· file<l' by Local No. 3. and at !· ~011gest ~iy st~ll,:/ on 1;eco1·d~th~n · _$ siune «fane ilismisse<l netitions fol' the electiofr fiH~l by} oy th0 tun~ '.'11s , go~s t9 pr?SS a!ltl ·. ·, : , ·. • : . • · ,· . · • · · , y ou get it,. tnere ·. ~v 11J 1i1·oha.bly be tllf:lSe tvvo q:nnpames. I . ' . ' . .' ~ I floo<ls'-everJ'.,:here. At : lill)''c rate The· complafot._ issu!),d aft1=r in- i !}aig·n,, aga!llS> that Company ~nd , that's how sh e . stands as of the ·e~ti.gat-ion. of -th e fads by tlie rep~···I ,mply '.n g ,that the u_mL.'U)l~ll lauor ; se_c;o nci t,;eei~ ,. -

Logistics M&A Industry Update

Issue: August 30, 2013 Logistics M&A Industry Update The McLean Group | www.mcleanllc.com | 703.827.0200 Industry Snapshot Five Weeks Ending Friday, August 30, 2013 Industry News . C.H. Robinson Worldwide appointed Ivo Aris director of global forwarding for C.H. Robinson Europe. Mr. Aris is charged with leading continental growth and advancement of the global forwarding division. Livingston International appointed Steven Preston CEO following Peter Luit’s retirement after 16 years at the helm. UTi Worldwide opened new London operations, expanding its existing air cargo hub. Complete with X-ray screening, bonded storage and refrigerated capabilities, the 33,000 square foot building serves as its primary UK air and road facility while consolidating air cargo to and from other UK locations. OnTrac will expand its San Diego overnight delivery service’s operation to 84,000 square feet to support increased volume. UPS Freight opened its new 72-door East Indianapolis Service Center on August 12. The new facility serves eastern Greater Indianapolis, complementing an existing 80-door Indianapolis Service Center that now serves the western metropolitan area. Expeditors International of Washington, Inc. reported Q2 2013 profits of $92.3 million, up 10.0% vs. Q2 2012’s $84.0 million. However, Q2 revenue slipped 0.3% year-over-year to $1.5 billion. C.H. Robinson Worldwide reported Q2 net income of $111.9 million, a 2.4% decline vs. Q2 2012’s $114.6 million. Q2 2013 revenue rose 11.3% to $3.3 billion, vs. $3.0 billion in Q2 2012. Notable M&A Activity Capital Markets (% Change) . -

Can Company 013230

PLEASE CONFIRM CSIP ELIGIBILITY ON THE DEALER SITE WITH THE "CSIP ELIGIBILITY COMPANIES" CAN COMPANY 013230 . Muller Inc 022147 110 Sand Campany 014916 1994 Steel Factory Corporation 005004 3 M Company 022447 3d Company Inc. 020170 4 Fun Limousine 021504 412 Motoring Llc 021417 4l Equipment Leasing Llc 022310 5 Star Auto Contruction Inc/Certified Collision Center 019764 5 Star Refrigeration & Ac, Inc. 021821 79411 Usa Inc. 022480 7-Eleven Inc. 024086 7g Distributing Llc 019408 908 Equipment (Dtf) 024335 A & B Business Equipment 022190 A & E Mechanical Inc. 010468 A & E Stores, Inc 018519 A & R Food Service 018553 A & Z Pharmaceutical Llc 005010 A A A - Corp. Only 022494 A A Electric Inc. 022751 A Action Plumbing Inc. 009218 A B C Contracting Co Inc 015111 A B C Parts Intl Inc. 018881 A Blair Enterprises Inc 019044 A Calarusso & Son Inc 020079 A Confidential Transportation, Inc. 022525 A D S Environmental Inc. 005049 A E P Industries 022983 A Folino Contruction Inc. 005054 A G F A Corporation 013841 A J Perri Inc 010814 A La Mode Inc 024394 A Life Style Services Inc. 023059 A Limousine Service Inc. 020129 A M Castle & Company 007372 A O N Corporation 007741 A O Smith Water Products 019513 A One Exterminators Inc 015788 A P S Security Inc 005207 A T & T Corp 022926 A Taste Of Excellence 015051 A Tech Concrete Co. 021962 A Total Plumbing Llc 012763 A V R Realty Company 023788 A Wainer Llc 016424 A&A Company/Shore Point 017173 A&A Limousines Inc 020687 A&A Maintenance Enterprise Inc 023422 A&H Nyc Limo / A&H American Limo 018432 A&M Supernova Pc 019403 A&M Transport ( Dtf) 016689 A. -

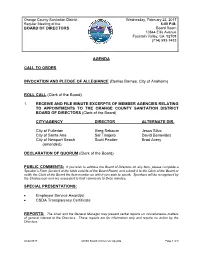

02-22-2017 Board Meeting Agenda

Orange County Sanitation District Wednesday, February 22, 2017 Regular Meeting of the 6:00 P.M. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Board Room 10844 Ellis Avenue Fountain Valley, CA 92708 (714) 593-7433 AGENDA CALL TO ORDER INVOCATION AND PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE (Denise Barnes, City of Anaheim) ROLL CALL (Clerk of the Board) 1. RECEIVE AND FILE MINUTE EXCERPTS OF MEMBER AGENCIES RELATING TO APPOINTMENTS TO THE ORANGE COUNTY SANITATION DISTRICT BOARD OF DIRECTORS (Clerk of the Board) CITY/AGENCY DIRECTOR ALTERNATE DIR. City of Fullerton Greg Sebourn Jesus Silva City of Santa Ana Sal Tinajero David Benavides City of Newport Beach Scott Peotter Brad Avery (amended) DECLARATION OF QUORUM (Clerk of the Board) PUBLIC COMMENTS: If you wish to address the Board of Directors on any item, please complete a Speaker’s Form (located at the table outside of the Board Room) and submit it to the Clerk of the Board or notify the Clerk of the Board the item number on which you wish to speak. Speakers will be recognized by the Chairperson and are requested to limit comments to three minutes. SPECIAL PRESENTATIONS: • Employee Service Award(s) • CSDA Transparency Certificate REPORTS: The Chair and the General Manager may present verbal reports on miscellaneous matters of general interest to the Directors. These reports are for information only and require no action by the Directors. 02/22/2017 OCSD Board of Directors’ Agenda Page 1 of 8 CONSENT CALENDAR: Consent Calendar Items are considered to be routine and will be enacted, by the Board of Directors, after one motion, without discussion. -

Alabama State Treasury (10/28/20)

09/29/21 05:28:43 Alabama State Treasury (10/28/20) Auction Opens: Fri, Oct 16 8:00am CT Auction Closes: Wed, Oct 28 8:00am CT Lot Title Lot Title 9293 WATCH & 14K BRACELET 9317 MORGAN & PEACE DOLLARS 9294 14K RING 9318 LIBERTY, FRANKLIN & KENNEDY 9295 SPORTS CARDS, BASEBALL & 10K HALVES & QUARTERS NECKLACE <BR><span style=color:red>- 9319 PEACE DOLLAR, NICKELS, PENNIES & NO CREDIT CARDS</span> FOREIGN 9296 MORGAN, EISENHOWER DOLLARS & 9320 WALKING LIBERTY DOLLAR, KENNEDY MINT SET HALVES & FOREIGN 9297 AMERICAN EAGLE WALKING LIBERTY 9321 COIN SET, PENNIES & FOREIGN COINS 9322 1881-O MORGAN DOLLAR 9298 AMERICAN EAGLE WALKING LIBERTY & 9323 $1 BILL, EARRINGS & SILVER FOREIGN BRACELET, NECKLACE 9299 ALABAMA STATE CHAMPIONSHIP CASE KNIFE 9300 14K RING 9301 1861 CONFEDERATE $100 NOTE 9302 10K BUTTERFLY RING 9303 FOREIGN CURRENCY - EUROS 9304 1878 MORGAN DOLLAR 7/8 TAIL FEATHERS 9305 AMERICAN EAGLE & SILVER ROUNDS 9306 FOREIGN COINS & PENNY 9307 SPORTS CARD, FOREIGN BILLS & SILVER NECKLACE <BR><span style=color:red>- NO CREDIT CARDS</span> 9308 MORGAN DOLLAR, KENNEDY HALVES, QUARTERS & DIMES 9309 PEARL NECKLACE, $1 SILVER CERTS. & SILVER BRACELET 9310 14K RING & 14K EARRINGS 9311 14K RINGS 9312 10K & 14K RINGS 9313 14K PENDANT & 14K BRACELET 9314 NECKLACES, 14K NECKLACE & 14K PENDANT 9315 14K NECKLACE & 14K PENDANT 9316 ROLEX WATCH FACE ONLY 1/5 09/29/21 05:28:43 2/5 09/29/21 05:28:43 Full and complete payment must be received within 3 business days of auction close at Lone Star Auctioneers' Fort Worth Office: 4629 Mark IV Parkway, Fort Worth, Texas 76106, between the workday hours of 8:00 AM and 5:00 PM Central Time. -

2020 Top 100 For-Hire Carriers Is an Annual Publication Produced by Transport Topics, with Assistance from SJ Consulting Group

COVID-19 Pandemic Muddles Outlook For Top 100 For-Hire Carriers he COVID-19 pandemic has transformed 2020 into a chal- Indianapolis, had ranked No. 38 a year ago. lenging and unprecedented year for the trucking industry. Meanwhile, familiar names continue to dominate the top of the T Freight networks faced major disruptions as businesses tem- 2020 list of North America’s largest for-hire carriers. Parcel giant porarily closed and people stayed home to help contain the spread of UPS Inc. remains firmly entrenched at No. 1, followed closely by the virus, bringing much of the economy to a standstill. rival FedEx Corp. Schneider, meanwhile, cracked the top 5 by edging past YRC Worldwide and Knight-Swift Transportation Holdings. Further down the list, several other carriers made notable jumps. Day & Ross Transportation Group, based in Hartland, New Bruns- Seth Clevenger wick, climbed to No. 37, from No. 46 a year ago. The Canadian car- rier ex panded its dedicated operations in the United States through Managing Editor, Features its April 2019 acquisition of A&S Kinard and Buckler Transport. Refrigerated carrier John Christner Trucking also continued its ascent. The Sapulpa, Okla.-based company’s ranking increased this year to No. 83, from No. 89 a year ago and No. 99 in 2018. Another big mover was Challenger Group, based in Cambridge, This public health crisis has forced North America’s largest for-hire Ontario. The company rose to No. 84, from No. 95 last year, as rev- carriers to adjust their operations while implementing safety mea- enue increased 17.5%. -

Annual Information Form for the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2020

ANNUAL INFORMATION FORM FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2020 February 18, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS……………………………………………………….... 3 ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE…………………...……………………………………….... 4 GENERAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE BUSINESS……………………………………………. 6 STRATEGIC ACQUISITIONS & DISPOSITIONS…………...…………………………........ 9 DESCRIPTION OF THE BUSINESS……………………………………………………………. 10 TRENDS………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 11 EQUIPMENT……………………………………………………………………………………. 11 LICENSES………………………………………………………………………………………. 11 MARKETS AND DISTRIBUTION……………………………………………………………... 11 SEASONALITY OF OPERATIONS…………………………………………………………... 11 REVENUES (IN PERCENTAGES)…………………………………………………………… 12 COMPETITION…………………………………………………………………………………. 12 HUMAN RESOURCES………………………………………………………………………… 12 ENVIRONMENTAL MATTERS……………………………………………………………….. 13 TRADEMARKS…………………………………………………………………………………. 13 RISK-FACTORS…………………………………………………………………………………... 14 DIVIDENDS………………………………………………………………………………………... 14 DESCRIPTION OF CAPITAL STRUCTURE…………………………………………………… 14 COMMON SHARES……………………………………………………………………………. 15 PREFERRED SHARES………………………………………………………………………… 15 MARKET FOR SECURITIES…………………………………………………………………….. 16 DIRECTORS AND OFFICERS………………………………………………………………….. 17 CONFLICTS OF INTEREST…………………………………………………………………... 21 AUDIT COMMITTEE……………………………………………………………………………… 22 LEGAL PROCEEDINS AND REGULATORY ACTIONS……………………………………… 23 INTEREST OF MANAGEMENT AND OTHERS IN MATERIAL TRANSACTIONS………... 24 TRANSFER AGENTS AND REGISTRARS...………………………………………………….. 24 MATERIAL CONTRACTS……………………………………………………………………….. -

2013 Top 100 For-Hire

A Word From the Publisher t’s been 32 years since the trucking industry supports “anything that makes it hard to get into was officially “deregulated,” which meant and hard to stay in this industry.” the federal government would no longer Carriers that are able to meet new regulations will regulate freight rates and services. Passage be the ones that prosper in the future, according to of the Motor Carrier Act of 1980 unleashed Williams’ point of view. Ipowerful market forces that continue to reshape the Not surprisingly, there are others who believe that industry today. federal oversight of trucking is going too far. But trucking today is far from being unregulated. “We’re the most over-reregulated industry out In fact, you could argue that it is more regulated there,” said Michael Card, president of Combined than ever before. Transport Inc. and current chairman of American How can that be? Consider that Trucking Associations. over the past three decades, in the Card said the cost of meeting new name of highway safety, the federal regulations, such as driver hours-of- government has mandated drug and service, drug testing and onboard alcohol testing and set minimum li - recorders, will force many carriers censing requirements for drivers, out of business and will discourage funded state-run roadside inspection others from starting up. programs, increased by one hour the “They’re all great regulations, but maximum time a driver can be be - almost all of them have raised the hind the wheel and cut by one hour cost of owning a trucking company,” the maximum time a driver can be he said. -

Last Mile Package Delivery Via Rural Transit: Project Summary and Pilot Outcomes

TTI: 0-6891 Last Mile Package Delivery via Rural Transit: Project Summary and Pilot Outcomes Technical Report 0-6891-R1 Cooperative Research Program TEXAS A&M TRANSPORTATION INSTITUTE COLLEGE STATION, TEXAS in cooperation with the Federal Highway Administration and the Texas Department of Transportation http://tti.tamu.edu/documents/0-6891-R1.pdf Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. FHWA/TX-17/0-6891-R1 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date LAST MILE PACKAGE DELIVERY VIA RURAL TRANSIT: Published: January 2019 PROJECT SUMMARY AND PILOT OUTCOMES 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Zachary Elgart, Kristi Miller, and Shuman Tan Report 0-6891-R1 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Texas A&M Transportation Institute The Texas A&M University System 11. Contract or Grant No. College Station, Texas 77843-3135 Project 0-6891 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Texas Department of Transportation Technical Report: Research and Technology Implementation Office September 2015–August 2017 125 E. 11th Street 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Austin, Texas 78701-2483 15. Supplementary Notes Project performed in cooperation with the Texas Department of Transportation and the Federal Highway Administration. Project Title: Using Public Transportation to Facilitate Last Mile Package Delivery URL: http://tti.tamu.edu/documents/0-6891-R1.pdf 16. Abstract Rural transit districts and intercity bus carriers are an important link within Texas’ multimodal transportation system. Without such service providers, many rural residents that are transit dependent would be forced to either relocate or find other means of transportation. -

Fall 2020 Fall North Dakota Motor Carriers Association Publication

FALL 2020 FALL NORTH DAKOTA MOTOR CARRIERS ASSOCIATION PUBLICATION REP. BOB LATTA INTRODUCES SELF-DRIVING VEHICLE LEGISLATION page 4 NDMCA ANNUAL SAFETY AWARDS page 10 TRUCKER PAY INCREASING AS DRIVER SHORTAGE GROWS page 18 CONTENTS FALL 2020 ndmca.org [email protected] facebook.com/ndmca 03 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE 1937 East Capitol Avenue 03 VISION CAMPAIGN P.O. Box 874 Bismarck, ND 58502 05 THANK YOU SPONSORS 701.223.2700 Fax: 701.258.8865 05 SAVE THE DATE – ANNUAL CONVENTION AND FOUNDATION SCHOLARSHIP GOLF TOURNAMENT NDMCA OFFICERS PRESIDENT TREASURER 09 NEW FEATURES IN WSI ONLINE PORTAL Pat Severson Wally Keller TMI Transport Corporation Jobbers Moving & Storage 10 NDMCA ANNUAL SAFETY AWARDS FIRST VICE PRESIDENT IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT 14 ANNUAL FOUNDATION SCHOLARSHIP GOLF TOURNAMENT Eric Grove Melissa Dixon Magnum, LTL Dixon Insurance Inc. SECOND VICE PRESIDENT ATA VICE PRESIDENT INDUSTRY NEWS Eric Bischke James Johannesson Cross Country Freight Solutions Inc. Magnum, LTL 04 REP. BOB LATTA INTRODUCES SELF-DRIVING VEHICLE LEGISLATION NDMCA DIRECTORS 06 CARRIERS PREPARE FOR INCREASING SURGE Karla Bancroft Marlin Kling TO SUPPLY CHAIN IN E-COMMERCE PUSH Holland Enterprises, Inc. Midwest Motor Express Inc. Kevin Borseth Kelly Krapu 09 EROAD GO HELPS FLEETS MANAGE PICKUP AND Midland Garage Door Interstate Truck Licensing/ DELIVERY OPERATIONS Compliance Solutions Tracy Buzick EW Wylie Corp. Casey Lindgren 18 TRUCKER PAY INCREASING AS DRIVER SHORTAGE GROWS Wallwork Truck Center Matthew Clark Cross Country Freight Solutions Inc. Matthew Mrotek Penske Truck Leasing Alan Coldwell Diamond B. Trucking Ryan Nelson Nelson International Nate Dahl Ryder Systems Inc. Jeremy Oistad Butler Machinery Kristal Fiser United Parcel Service Teri Lynn Steckler The North Dakota Motor Carriers Wyoming Casing Service Matt Gadberry Association has been publishing the Magnum LTD Dale Strege Rolling Along magazine since 1948. -

Bcos, Maximize YOUR Opportunities

The Landstar IN THIS ISSUE Free Holiday Meals for BCOs ...............3 2018-19 Landstar Scholarship Fund ......5 New Landstar Available Loads app .......6 Link Fall 2017 TRANSPORTATION MANAGEMENT SOLUTIONS•TRUCKLOAD•LTL•HEAVY HAUL/SPECIALIZED•EXPEDITED•AIR•OCEAN•RAIL INTERMODAL BCOs, Maximize YOUR Opportunities Landstar is launching another great A Landstar BCO logs into the app, inputs his Save the technology tool to help independent or her origin and ultimate destination, trailer owner-operators run their businesses more type, and the start and end dates for the days Dates effectively. Soon, Landstar owner-operators of desired travel. Once all the search criteria can use the new Landstar Maximizer™ is entered, the ASK MAX™ button can Mark your calendars with the dates for mobile app to do the leg work of finding generate hundreds of multileg combinations four great Landstar events in 2018. multileg runs. The app, which has been in for the user to choose from. The BCO selects beta testing with Landstar business capacity the right combination for his or her plans, Landstar BCO Appreciation Days owners (BCOs), helps users plan loads ahead and calls each agent listed to book a multileg, March 8-9, 2018 of time – at the same time! Simply put, the revenue- and time-maximizing trip. Cendera Center app searches through thousands of loads in The Landstar Maximizer mobile app next 3600 Benbrook Highway Landstar’s available loads database to find searches available loads from Landstar’s Ft. Worth, Texas the best combinations of back-to-back loads, load board, provides the best combinations allowing BCOs to identify and book multileg, matching the search criteria, and displays the Landstar Agent Convention full-week runs.