Last Mile Package Delivery Via Rural Transit: Project Summary and Pilot Outcomes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

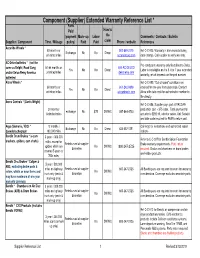

Component (Supplier) Extended Warranty Reference List *

Component (Supplier) Extended Warranty Reference List * Parts Paid How to (payment Mark- up Labor file Comments / Contacts / Bulletin Supplier / Component Time / Mileage policy) Paid Paid claim Phone / website References Accuride Wheels * 60 months or 800-869-2275 Ref C-C-005. Warranty is from manufacturing Exchange No No Direct unlimited miles accuridecorp.com date (stamp). Call supplier to verify warranty. AC-Delco batteries * (not the Pro-rated parts warranty only filed direct to Delco. same as Delphi, Road Gang 60-84 months or 800-AC-DELCO Yes No No Direct Labor is not eligible on the 5, 6 or 7 year extended and/or Delco Remy America unlimited miles delcoremy.com warranty, which depends on the part number. batteries) Alcoa Wheels * Ref C-C-099. "Out of round" conditions are 60 months or 800-242-9898 covered for one year from date code. Contact Yes No No Direct unlimited miles alcoawheels.com Alcoa with date code for authorization number to file directly. Arens Controls * (Curtis Wright) Ref C-C-056. Supplier pays part at PACCAR 24 months/ production cost + $75 labor. Total payment for exchange No $75 DWWC 847-844-4703 Unlimited miles actuator is $292.19, selector varies. Unit Serial # and date code required for RMA to return part. Argo (Siemen's, VDO) * 12 months / Call Argo for instructions and authorized repair Exchange No No Direct 425-557-1391 Speedo/tachograph 100,000 miles stations. Bendix Drum Brakes * (s-cam 3 years / 300,000 Refer to C-C-007 for Bendix Spicer Foundation brackets, spiders, cam shafts) miles, except for Reimbursed at supplier Brake warranty requirements. -

Fedex Ground Contractor Operating Agreement

OP-149 FEDEX GROUND {ACKAGE SYSTEM, INC. PICK-UP AND DELIVERY CONTRACTOR OPERATING AGREEMENT. JUNE 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND STATEMENT ................................................................................................... I 1. EQUIPMENT AND OPERA nONS ........................................................................................ 2 1.1 Power Equipment. ....................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Equipment Maintenance ............................................................................................. 2 1.3 Operating Expenses. ........... .............. .... ...... ........... .............. .................... ..... ..... ......... 3 1.4 Operation of the Equipment. ....................................................................................... 3 1.5 Equipment Identification while in FedEx Ground's Service ....................................... 4 1.6 Licensing ..................................................................................................................... 4 1.7 Logs and Reports. .......................................... ............................ .............. ................... 5 1.8 Shipping Documents and Collections ......................................................................... 5 1.9 Contractor Performance Escrow Account ................................................................... 5 1.10 Agreed Standard of Service ..................................................................................... -

In the United States District Court for the District of Connecticut

Case 3:15-cv-01550-JAM Document 120 Filed 06/27/17 Page 1 of 45 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF CONNECTICUT CARLOS TAVERAS, individually and on behalf of all others similarly situated, Plaintiff, C.A. No. 3:15-cv-01550-JAM v. XPO LAST MILE, INC. Defendant. XPO LAST MILE, INC. Third-Party Plaintiff, v. EXPEDITED TRANSPORT SERVICES, LLC. Third-Party Defendant. PLAINTIFF’S ASSENTED-TO MOTION FOR FINAL APPROVAL OF A CLASS ACTION SETTLEMENT Plaintiff filed this lawsuit on behalf of himself and a class of similarly situated delivery drivers who performed delivery services for Defendant XPO Last Mile, Inc. in Connecticut pursuant to standard contracts under which they were classified as independent contractors. Plaintiff alleges that XPO’s delivery contractors were actually employees, and based on this misclassification, XPO’s practice of making deductions from its delivery drivers’ pay for such things as damage claims and worker’s compensation violates the Connecticut wage payments laws. Conn. Gen. Stat. Sec. 31-71e. The parties have reached a non-reversionary class action settlement for $950,000. 1 Case 3:15-cv-01550-JAM Document 120 Filed 06/27/17 Page 2 of 45 On March 17, 2017, the Court granted preliminary approval of the proposed settlement, certified a class of individuals who performed delivery services for Defendant XPO Last Mile, Inc. in Connecticut pursuant to contracts that class them as independent contractors, and authorized notice to the class. ECF No. 115. Plaintiff now seeks the Court’s final approval of the proposed class action settlement at the final settlement approval hearing scheduled for July 7, 2017. -

Express Rules and Regulations

Greyhound Lines, Inc. PACKAGE EXPRESS TARIFF AND SALES MANUAL Created and maintained by Revenue Development Department email: [email protected] GREYHOUND LINES, INC. PACKAGE EXPRESS TARIFF AND SALES MANUAL EXPRESS RULES, REGULATIONS, RATES, AND CHARGES Table of Contents Page Instructions and contacts ................................................................................................................................................................. 1.5 Carriers -- Local and Interline .......................................................................................................................................................... 1.6 Carriers -- Interline only....................................................................................................................................................1.6 and 1.7 Determination of Applicable Express Rate Zones ........................................................................................................................... 1.8 Packing, Marking, Labeling, and Conditions of Acceptance ............................................................................................................ 1.8 Dimensional Weight Surcharge ....................................................................................................................................................... 1.9 Determination of Charges for Shipments Weighing in Excess of One Hundred Pounds ................................................................ 1.9 Types of Service Defined -

GAO-15-641, MOTOR CARRIER SAFETY: Additional Research Standards and Truck Drivers' Schedule Data Could Allow More Accurate A

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Requesters July 2015 MOTOR CARRIER SAFETY Additional Research Standards and Truck Drivers’ Schedule Data Could Allow More Accurate Assessments of the Hours of Service Rule GAO-15-641 July 2015 MOTOR CARRIER SAFETY Additional Research Standards and Truck Drivers’ Schedule Data Could Allow More Accurate Assessments of the Hours of Service Rule Highlights of GAO-15-641, a report to congressional requesters Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found FMCSA—within the Department of GAO found that the January 2014 study issued by the Federal Motor Carrier Transportation (DOT)—issues rules to Safety Administration (FMCSA) to examine the efficacy of its hours of service address safety concerns of the motor (HOS) rule—a regulation that governs how many hours truck drivers transporting carrier industry, including on truck freight can work—followed most generally accepted research standards. drivers’ HOS. In July 2013, FMCSA However, FMCSA did not completely meet certain research standards such as began to enforce three new provisions reporting limitations and linking the conclusions to the results. For example, by of its HOS rule. GAO was asked to not adhering to these standards, FMCSA’s conclusion in the study about the review a 2014 FMCSA study on the extent to which crash risk is reduced by the HOS rule may be overstated. GAO rule, as well as the rule’s assumptions found that FMCSA has not adopted guidance on the most appropriate methods and effects. This report (1) compares for designing, analyzing, and reporting the results of scientific research. Without the study to generally accepted research standards, and (2) identifies such guidance, FMCSA may be at risk for excluding critical elements in research the assumptions used to estimate the it undertakes to evaluate the safety of its rules, leaving itself open to criticism. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

On the Brink: 2021 Outlook for the Intercity Bus Industry in the United States

On the Brink: 2021 Outlook for the Intercity Bus Industry in the United States BY JOSEPH SCHWIETERMAN, BRIAN ANTOLIN & CRYSTAL BELL JANUARY 30, 2021 CHADDICK INSTITUTE FOR METROPOLITAN DEVELOPMENT AT DEPAUL UNIVERSITY | POLICY SERIES THE STUDY TEAM AUTHORS BRIAN ANTOLIN, JOSEPH P. SCHWIETERMAN AND CRYSTAL BELL CARTOGRAPHY ALL TOGETHER STUDIO AND GRAPHICS ASSISTING MICHAEL R. WEINMAN AND PATRICIA CHEMKA SPERANZA OF PTSI TRANSPORTATION CONTRIBUTORS DATA KIMBERLY FAIR AND MITCH HIRST TEAM COVER BOTTOM CENTER: ANNA SHVETS; BOTTOM LEFT: SEE CAPTION ON PAGE 1; PHOTOGRAPHY TOP AND BOTTOM RIGHT: CHADDICK INSTITUTE The Chaddick Insttute does not receive funding from intercity bus lines or suppliers of bus operators. This report was paid for using general operatng funds. For further informaton, author bios, disclaimers, and cover image captons, see page 20. JOIN THE STUDY TEAM FOR A WEBINAR ON THIS STUDY: Friday, February 19, 2021 from noon to 1 pm CT (10 am PT) | Free Email [email protected] to register or for more info CHADDICK INSTITUTE FOR METROPOLITAN DEVELOPMENT AT DEPAUL UNIVERSITY CONTACT: JOSEPH SCHWIETERMAN, PH.D. | PHONE: 312.362.5732 | EMAIL: [email protected] INTRODUCTION The prognosis for the intercity bus industry remains uncertain due to the weakened financial condition of most scheduled operators and the unanswerable questions about the pace of a post-pandemic recovery. This year’s Outlook for the Intercity Bus Industry report draws attention to some of the industry’s changing fundamentals while also looking at notable developments anticipated this year and beyond. Our analysis evaluates the industry in six areas: i) The status of bus travel booking through January 2021; ii) Notable marketing and service developments of 2020; iii) The decline of the national bus network sold on greyhound.com that is relied upon by travelers on thousands of routes across the U.S. -

Washington DC Marriott Wardman Park Hotel Shipping Instructions

Washington DC Marriott Wardman Park Hotel Shipping Instructions PREPARING YOUR SHIPMENT FedEx Office is committed to providing you with an outstanding experience during your stay. All guest and event packages be- ing shipped to the property must follow the address label standards (illustrated below) to prevent package routing delays. Please schedule your shipment(s) to arrive four days prior to the event start date to avoid additional storage fees. Use the name of the recipient who will be on-site to receive and sign for the package(s). Please do not address shipments using property employee names, unless the items are specifically for their use (e.g., hotel specifications, rooming lists, or signed documents); this includes arranging for deliveries to all areas on the property. If a package has not been picked up by the recipient and no contact information is provided, the package will be returned to the sender, who will be responsible for all additional shipping fees. For more information on package retention, the Return to Sender process, or to schedule package deliveries, please contact the FedEx Office Business Center at 202.986.4028. Package deliver- ies should only be scheduled after the recipient has completed the check-in process. PACKAGE LABELING STANDARDS AND FEDEX OFFICE CONTACT (Guest Name) (Guest Cell Number) FedEx Office Business Center Operating Hours c/o FedEx Office at Washington DC Marriott Wardman Washington DC Marriott Mon – Fri: 7:00am - 7:00pm Park Hotel Wardman Park Hotel Saturday: Closed 2600 Woodley Road NW 2600 Woodley Road NW Sunday: Closed Washington, DC, 20008 Washington, DC 20008 (Convention / Conference / Group / Event Name) Phone: 202.986.4028 Box ____ of ____ Fax: 202.986.4728 Email: [email protected] SHIPMENTS WITH SPECIAL REQUIREMENTS Meeting and event planners, exhibitors and attendees are encouraged to contact FedEx Office in advance of shipping their items to Washington DC Marriott Wardman Park Hotel with any specific questions. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT of INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION in Re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMEN

USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 1 of 354 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION ) Case No. 3:05-MD-527 RLM In re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE ) (MDL 1700) SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMENT ) PRACTICES LITIGATION ) ) ) THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO: ) ) Carlene Craig, et. al. v. FedEx Case No. 3:05-cv-530 RLM ) Ground Package Systems, Inc., ) ) PROPOSED FINAL APPROVAL ORDER This matter came before the Court for hearing on March 11, 2019, to consider final approval of the proposed ERISA Class Action Settlement reached by and between Plaintiffs Leo Rittenhouse, Jeff Bramlage, Lawrence Liable, Kent Whistler, Mike Moore, Keith Berry, Matthew Cook, Heidi Law, Sylvia O’Brien, Neal Bergkamp, and Dominic Lupo1 (collectively, “the Named Plaintiffs”), on behalf of themselves and the Certified Class, and Defendant FedEx Ground Package System, Inc. (“FXG”) (collectively, “the Parties”), the terms of which Settlement are set forth in the Class Action Settlement Agreement (the “Settlement Agreement”) attached as Exhibit A to the Joint Declaration of Co-Lead Counsel in support of Preliminary Approval of the Kansas Class Action 1 Carlene Craig withdrew as a Named Plaintiff on November 29, 2006. See MDL Doc. No. 409. Named Plaintiffs Ronald Perry and Alan Pacheco are not movants for final approval and filed an objection [MDL Doc. Nos. 3251/3261]. USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 2 of 354 Settlement [MDL Doc. No. 3154-1]. Also before the Court is ERISA Plaintiffs’ Unopposed Motion for Attorney’s Fees and for Payment of Service Awards to the Named Plaintiffs, filed with the Court on October 19, 2018 [MDL Doc. -

Standard Reference Marks for Greyhound Lines

STANDARD REFERENCE MARKS FOR GREYHOUND LINES All schedules operate daily unless otherwise noted Frequency Codes 1 Monday 4 Thursday 7 Sunday 2 Tuesday 5 Friday H Holiday 3 Wednesday 6 Saturday X Except Example: X67H Equals Except Saturday, Sunday, Holiday Holiday Service New Year's Day, President's Day (where specified), Memorial Day, Fourth of July, Labor Day, Thanksgiving and Christmas Standard Symbols/Abbreviations r Break or Meal Stop AR Arrive D Stops only to discharge passengers at agency or in town. Times shown are approximate. DH Discharge at highway interchange dh Deadhead E Stops at agency only to discharges passengers or express. Times shown are approximate. f Flag stop. Bus will stop on signal to receive and discharge passengers. h Holds for connection HS Highway stop - does not go into town or agency. LV Leave R Restricted service between points indicated Carrier Codes GL Greyhound Lines, Inc. NYT New York Trailways ADT Adirondack Trailways ORB Orange Belt Stages CCC Carolina Trailways PPB Peter Pan Trailways CML Capitol Motor Lines SES Southeastern Stages COT Colonial Trailways TNO Texas, New Mexico & Oklahoma Coaches CPB Capitol Trailways of Pennsylvania VT Vermont Transit JL Jefferson Lines VTC Valley Transit KBC Kerrville Bus Company Time Zones ET Eastern Time MT Mountain Time EST Eastern Standard Time MST Mountain Standard Time EDT Eastern Daylight Time MDT Mountain Daylight Time CT Central Time PT Pacific Time CST Central Standard Time PST Pacific Standard Time CDT Central Daylight Time PDT Pacific Daylight Time. -

Scope of Using Autonomous Trucks and Lorries for Parcel Deliveries in Urban Settings

logistics Article Scope of Using Autonomous Trucks and Lorries for Parcel Deliveries in Urban Settings Evelyne Tina Kassai, Muhammad Azmat * and Sebastian Kummer Welthandelsplatz 1, Institute for Transport and Logistics Management, WU (Vienna University of Economics and Business), 1020 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] (E.T.K.); [email protected] (S.K.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 17 June 2020; Accepted: 21 July 2020; Published: 7 August 2020 Abstract: Courier, express, and parcel (CEP) services represent one of the most challenging and dynamic sectors of the logistics industry. Companies of this sector must solve several challenges to keep up with the rapid changes in the market. In this context, the introduction of autonomous delivery using self-driving trucks might be an appropriate solution to overcome the problems that the industry is facing today. This paper investigates if the introduction of autonomous trucks would be feasible for deliveries in urban areas from the experts’ point of view. Furthermore, the potential advantages of such autonomous vehicles were highlighted and compared to traditional delivery methods. At the same time, barriers that could slow down or hinder such an implementation were also discovered by conducting semi-structured interviews with experts from the field. The results show that CEP companies are interested in innovative logistics solutions such as autonomous vans, especially when it comes to business-to-consumer (B2C) activities. Most of the experts acknowledge the benefits that self-driving vans could bring once on the market. Despite that, there are still some difficulties that need to be solved before actual implementation. -

The Stepped Hull Hybrid Hydrofoil

The Stepped Hull Hybrid Hydrofoil Christopher D. Barry, Bryan Duffty Planing @brid hydrofoils or partially hydrofoil supported planing boat are hydrofoils that intentionally operate in what would be the takeoff condition for a norma[ hydrofoil. They ofler a compromise ofperformance and cost that might be appropriate for ferq missions. The stepped hybrid configuration has made appearances in the high speed boat scene as early as 1938. It is a solution to the problems of instability and inefficiency that has limited other type of hybrids. It can be configured to have good seakeeping as well, but the concept has not been used as widely as would be justified by its merits. The purpose of this paper is to reintroduce this concept to the marine community, particularly for small, fast ferries. We have performed analytic studies, simple model experiments and manned experiments, andfiom them have determined some specljic problems and issues for the practical implementation of this concept. This paper presents background information, discusses key concepts including resistance, stability, seakeeping, and propulsion and suggests solutions to what we believe are the problems that have limited the widespread acceptance of this concept. Finally we propose a “strawman” design for a ferry in a particular service using this technology. BACKGROUND Partially hydrofoil supported planing hulls mix hydrofoil support and planing lift. The most obvious A hybrid hydrofoil is a vehicle combining the version of this concept is a planing hull with a dynamic lift of hydrofoils with a significant amount of hydrofoil more or less under the center of gravity. lit? tiom some other source, generally either buoyancy Karafiath (1974) studied this concept and ran model or planing lift.