Market Opportunities and Key Foreign Trade Restrictions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Perception of Mobile Phone User's of Bhubaneswar

SSRG International Journal of Economics and Management Studies (SSRG-IJEMS) – Volume 7 Issue 3–March 2020 A Study On Perception of Mobile Phone User’s of Bhubaneswar Towards Chinese Mobile Phone’s Quality Debasish Rout*, Dr Somabhusan Janakiballav Mishra**, Rahul Gupta*** *Asst Professor, Amity Global Business School, Bhubaneswar ** Asst Professor, Amity Global Business School, Bhubaneswar *** Student of MBA (Operations), Amity Global Business School, Bhubaneswar ABSTRACT With the advancement of technology and people perception and buying behavior has spanned over three becoming tech-savvy, Bhubaneswar market has become decades after India implemented “Open door policy” cosmopolitan as far as electronic gadgets are by inviting companies abroad to come to India and set concerned. People have become exposed to the cyber- up their manufacturing facilities. Immediately after environment and have become more and more risk LPG many American, Canadian, French, Chinese takers and early adapters. The buying behavior is so companies had invested in this vast Indian market dynamic that people are least bothered about price if which consists of more than 700 million middle class they get all the features they want. Internet has with purchasing power. Barring Chinese companies educated the consumers to such an extent that they almost all other companies have won the confidence of don‟t wait for promotion. Proactively they look for the the consumers in India. But there is a notion about the products to be released in the near future. But in spite Chinese products of not being durable and cheap. The of all these quality is a buzzword in today‟s world and study, therefore aims to examine the perceptions of the companies cannot ignore this important factor. -

Annual Report 2016

SoftBank Group Corp. ANNUAL REPORT 2016 Corporate Philosophy Information Revolution – Happiness for everyone Vision The corporate group needed most by people around the world SoftBank Group Corp. ANNUAL REPORT 2016 001 A History of Challenges A History of Challenges The view is different when you challenge yourself Continuing to take on new challenges and embrace change without fear. Driving business forward through exhaustive debate. This is the SoftBank Group’s DNA. SoftBank Group Corp. ANNUAL REPORT 2016 002 A History of Challenges Established SoftBank Japan. 1981 Commenced operations as a distributor of packaged software. 1982 Entered the publishing business. Launched Oh! PC and Oh! MZ, monthly magazines introducing PCs and software by manufacturer. 1994 Acquired events division from Ziff Communications Company of the U.S. through SoftBank Holdings Inc. 1996 Acquired Ziff-Davis Publishing Company, U.S. publisher of PC WEEK magazine and provider of leading-edge information on the PC industry. SoftBank Group Corp. ANNUAL REPORT 2016 003 A History of Challenges Established Yahoo Japan through joint investment with Yahoo! Inc. in the U.S. 1996 Began to develop into an Internet company at full scale. Yahoo Japan Net income* 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 FY (Note) Accounting standard: JGAAP up to fiscal 2012; IFRSs from fiscal 2013 onward. * Net income attributable to owners of the parent. SoftBank Group Corp. ANNUAL REPORT 2016 004 A History of Challenges Made full-scale entry into the telecommunications business. 2000s Contributed to faster, more affordable telecommunications services in Japan. -

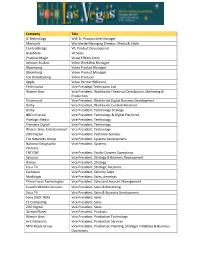

Company Title G-Technology WW Sr. Product Line Manager Microsoft

Company Title G-Technology WW Sr. Product Line Manager Microsoft Worldwide Managing Director, Media & Cable Contentbridge VP, Product Development GrayMeta VP Sales Practical Magic Visual Effects Artist Amazon Studios Video Workflow Manager Bloomberg Video Product Manager Bloomberg Video Product Manager Fox Broadcasting Video Producer Apple Video Partner Relations Technicolor Vice Presidept Technicolor Ltd Warner Bros. Vice President, Worldwide Theatrical Distribution, Marketing & Production Paramount Vice President, Worldwide Digital Business Development Dolby Vice President, Worldwide Content Relations Dolby Vice President, Technology Strategy NBCUniversal Vice President, Technology & Digital Platforms Pixelogic Media Vice President, Technology Premiere Digital Vice President, Technology Warner Bros. Entertainment Vice President, Technology ZOO Digital Vice President, Technical Services Fox Networks Group Vice President, Systems Development National Geographic Vice President, Systems Partners TNT/TBS Vice President, Studio Content Operations Synovos Vice President, Strategy & Business Development Disney Vice President, Strategy You.i TV Vice President, Strategic Accounts Cartesian Vice President, Security Sales MarkLogic Vice President, Sales, Americas Prime Focus Technologies Vice President, Sales and Account Management Crawford Media Services Vice President, Sales & Marketing You.i TV Vice President, Sales & Business Development Sony DADC NMS Vice President, Sales T2 Computing Vice President, Sales ZOO Digital Vice President, Sales -

Leading Indonesian Online Marketplace Tokopedia Secures $100 Million Investment from Softbank Internet and Media and Sequoia Capital

October 22, 2014 PT Tokopedia SoftBank Internet and Media, Inc. Sequoia Capital Leading Indonesian Online Marketplace Tokopedia Secures $100 Million Investment from SoftBank Internet and Media and Sequoia Capital Jakarta, Indonesia, San Carlos, CA, and Menlo Park, CA, October 22, 2014 — PT Tokopedia (“Tokopedia”), an online marketplace leader in Indonesia, SoftBank Internet and Media, Inc. (“SIMI”) and Sequoia Capital today announced a definitive agreement between SoftBank Corp. (“SoftBank”) and Tokopedia, among others, under which SIMI is expected to lead a financing round of approximately $100 million, with participation from Sequoia Capital and existing shareholder SB Pan Asia Fund. With this round of funding, SIMI and Sequoia Capital representatives will join the company’s board of directors. Founded in 2009, Tokopedia has grown rapidly to become Indonesia’s leading online marketplace. With this new capital, Tokopedia will focus on customer acquisition, hiring, and other initiatives to further strengthen its position as the No. 1 marketplace destination in Indonesia. By partnering with Tokopedia, SoftBank aims to further build its presence towards becoming the No. 1 Internet company in Asia and accelerate business growth by leveraging synergies with its other group Internet companies. William Tanuwijaya, CEO of Tokopedia said, “I’m very excited to welcome SIMI and Sequoia Capital as our new shareholders. I look forward to learning from them and taking Tokopedia to the next level. With this new round, Tokopedia will have enough resources to form the best team, develop world class technology to help our merchants and bring the best commerce experience to our users. We will always prioritize our users, and focus on making our users more successful. -

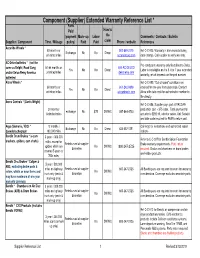

Component (Supplier) Extended Warranty Reference List *

Component (Supplier) Extended Warranty Reference List * Parts Paid How to (payment Mark- up Labor file Comments / Contacts / Bulletin Supplier / Component Time / Mileage policy) Paid Paid claim Phone / website References Accuride Wheels * 60 months or 800-869-2275 Ref C-C-005. Warranty is from manufacturing Exchange No No Direct unlimited miles accuridecorp.com date (stamp). Call supplier to verify warranty. AC-Delco batteries * (not the Pro-rated parts warranty only filed direct to Delco. same as Delphi, Road Gang 60-84 months or 800-AC-DELCO Yes No No Direct Labor is not eligible on the 5, 6 or 7 year extended and/or Delco Remy America unlimited miles delcoremy.com warranty, which depends on the part number. batteries) Alcoa Wheels * Ref C-C-099. "Out of round" conditions are 60 months or 800-242-9898 covered for one year from date code. Contact Yes No No Direct unlimited miles alcoawheels.com Alcoa with date code for authorization number to file directly. Arens Controls * (Curtis Wright) Ref C-C-056. Supplier pays part at PACCAR 24 months/ production cost + $75 labor. Total payment for exchange No $75 DWWC 847-844-4703 Unlimited miles actuator is $292.19, selector varies. Unit Serial # and date code required for RMA to return part. Argo (Siemen's, VDO) * 12 months / Call Argo for instructions and authorized repair Exchange No No Direct 425-557-1391 Speedo/tachograph 100,000 miles stations. Bendix Drum Brakes * (s-cam 3 years / 300,000 Refer to C-C-007 for Bendix Spicer Foundation brackets, spiders, cam shafts) miles, except for Reimbursed at supplier Brake warranty requirements. -

In the United States District Court for the District of Connecticut

Case 3:15-cv-01550-JAM Document 120 Filed 06/27/17 Page 1 of 45 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF CONNECTICUT CARLOS TAVERAS, individually and on behalf of all others similarly situated, Plaintiff, C.A. No. 3:15-cv-01550-JAM v. XPO LAST MILE, INC. Defendant. XPO LAST MILE, INC. Third-Party Plaintiff, v. EXPEDITED TRANSPORT SERVICES, LLC. Third-Party Defendant. PLAINTIFF’S ASSENTED-TO MOTION FOR FINAL APPROVAL OF A CLASS ACTION SETTLEMENT Plaintiff filed this lawsuit on behalf of himself and a class of similarly situated delivery drivers who performed delivery services for Defendant XPO Last Mile, Inc. in Connecticut pursuant to standard contracts under which they were classified as independent contractors. Plaintiff alleges that XPO’s delivery contractors were actually employees, and based on this misclassification, XPO’s practice of making deductions from its delivery drivers’ pay for such things as damage claims and worker’s compensation violates the Connecticut wage payments laws. Conn. Gen. Stat. Sec. 31-71e. The parties have reached a non-reversionary class action settlement for $950,000. 1 Case 3:15-cv-01550-JAM Document 120 Filed 06/27/17 Page 2 of 45 On March 17, 2017, the Court granted preliminary approval of the proposed settlement, certified a class of individuals who performed delivery services for Defendant XPO Last Mile, Inc. in Connecticut pursuant to contracts that class them as independent contractors, and authorized notice to the class. ECF No. 115. Plaintiff now seeks the Court’s final approval of the proposed class action settlement at the final settlement approval hearing scheduled for July 7, 2017. -

Startup Culture Isn't Just a Fad, Signals CXO Money Snapdeal Raises AGE of INVES1MENI'5 $500 M More'in a Fresh Round

The Economic Times August 3, 2015 Page No. 1 & 13 GUNGHOA poll of 100 C-sutte occupiers across companies has revealed that as ma~60% CXO-Ievel execs in India invested a portion of their wealth in startups Startup Culture isn't Just a Fad, Signals CXO Money Snapdeal Raises AGE OF INVES1MENI'5 $500 m more'in a Fresh Round 2VEARS Alibaba, Foxconn and 3YEARS_ SoftBank pick up stakes 4 YEARS. DealDIIest IN JA/IIUMv, AU- A MIX OFVALUA- 5-10YEARS baba started talks tIon mIsmaId1IS with SnapdeaI to and demand for !!10VEARS_ ,,-pick-,---,UP-,--stake~_-----lper10nnaIlCIHed 11 MAY,FOIIaNI metrIcs dI!Iayed NORESPONSE. too evinced interest dosure.of deal planned to open their wallets to this as- [email protected] set class in the coming months. As many as 79 CXOs said they would New Delhi: Jasper Infotech, which TEAM ET recommend investing in startups to oth- owns and operates online marketplace ers' although with an important caveat Snapdeal.com, has raised fresh capi- that these investments were risky and As many as six in 10 CXO-levelexecu- tal, estimated at about $500 million, in tives in India have invested a portion of investors needed to make them with a new round led by Chinese e-com- their wealth in startups, an ET poll of their eyes fully open. merce giant Alibaba Group and Tai- 100 randomly selected C-Suite occu- wanese electronics manufacturer piers across compa- Investlnlln Friends' Ventures •• 13 Foxconn, tech news startup Re/Code NBFCSQUEUE nies in a range of in- claimed late on Sunday. -

Read the SPUR 2012-2013 Annual Report

2012–2013 Ideas and action Annual Report for a better city For the first time in history, the majority of the world’s population resides in cities. And by 2050, more than 75 percent of us will call cities home. SPUR works to make the major cities of the Bay Area as livable and sustainable as possible. Great urban places, like San Francisco’s Dolores Park playground, bring people together from all walks of life. 2 SPUR Annual Report 2012–13 SPUR Annual Report 2012–13 3 It will determine our access to economic opportunity, our impact on the planetary climate — and the climate’s impact on us. If we organize them the right way, cities can become the solution to the problems of our time. We are hard at work retrofitting our transportation infrastructure to support the needs of tomorrow. Shown here: the new Transbay Transit Center, now under construction. 4 SPUR Annual Report 2012–13 SPUR Annual Report 2012–13 5 Cities are places of collective action. They are where we invent new business ideas, new art forms and new movements for social change. Cities foster innovation of all kinds. Pictured here: SPUR and local partner groups conduct a day- long experiment to activate a key intersection in San Francisco’s Mid-Market neighborhood. 6 SPUR Annual Report 2012–13 SPUR Annual Report 2012–13 7 We have the resources, the diversity of perspectives and the civic values to pioneer a new model for the American city — one that moves toward carbon neutrality while embracing a shared prosperity. -

Ignite Visibility Consulting

Ignite Visibility Consulting Copyright 2013 – Ignite Visibility Page 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Your Page ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 Branded URL ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Background and Profile Picture ................................................................................................................ 3 Fill out all Text ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Videos............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Theme your Videos Around One Keyword ............................................................................................... 4 Add a Date, Describe a Location, Link to Social Sites and Links to YouTube Video .................................. 5 Get Video Embeds, +1s, Ratings, Views and Comments Gradually .......................................................... 5 Add Annotations to Videos ........................................................................................................................... 5 Make Videos -

FLEXIBLE BENEFITS for the GIG ECONOMY Seth C. Oranburg* Federal Labor Law Requires Employers to Give

UNBUNDLING EMPLOYMENT: FLEXIBLE BENEFITS FOR THE GIG ECONOMY Seth C. Oranburg∗ ABSTRACT Federal labor law requires employers to give employees a rigid bundle of benefits, including the right to unionize, unemployment insurance, worker’s compensation insurance, health insurance, family medical leave, and more. These benefits are not free—benefits cost about one-third of wages—and someone must pay for them. Which of these benefits are worth their cost? This Article takes a theoretical approach to that problem and proposes a flexible benefits solution. Labor law developed under a traditional model of work: long-term employees depended on a single employer to engage in goods- producing work. Few people work that way today. Instead, modern workers are increasingly using multiple technology platforms (such as Uber, Lyft, TaskRabbit, Amazon Flex, DoorDash, Handy, Moonlighting, FLEXABLE, PeoplePerHour, Rover, Snagajob, TaskEasy, Upwork, and many more) to provide short-term service- producing work. Labor laws are a bad fit for this “gig economy.” New legal paradigms are needed. The rigid labor law classification of all workers as either “employees” (who get the entire bundle of benefits) or “independent contractors” (who get none) has led to many lawsuits attempting to redefine who is an “employee” in the gig economy. This issue grows larger as more than one-fifth of the workforce is now categorized as an independent contractor. Ironically, the requirement to provide a rigid bundle of benefits to employees has resulted in fewer workers receiving any benefits at all. ∗ Associate Professor, Duquesne University School of Law; Research Fellow and Program Affiliate Scholar, New York University School of Law; J.D., University of Chicago Law School; B.A., University of Florida. -

Statement of the Alphabet Workers Union on “The Misinformation And

Statement of the Alphabet Workers Union On “the Misinformation and Disinformation Plaguing Online Platforms” Before the House Energy and Commerce Committee March 25, 2021 March 25, 2021 Workers across Alphabet have previously organized against the company's continued refusal to take meaningful action to stop the proliferation of hate, harassment, incitement of violence, or harmful misinformation from YouTube and other Alphabet-operated platforms, without good faith engagement from leadership. Alphabet is responsible for directly contributing to harmful misinformation campaigns that fuel fascist, white nationalist and hateful movements that perpetrate violence in the United States and around the world. While much attention has been paid to YouTube and other online platforms’ role in radicalizing white supremacists, this hearing is also an opportunity to illuminate how these technologies contribute to dangerous disinformation movements including QAnon, “Patriot” militias, and anti-vaccine advocacy. (1), (2). Alphabet has demonstrated a continued policy of reactive, selective and insufficient enforcement of its guidelines against disinformation and hate. As a union that fights for, and welcomes the contributions of, every worker in Alphabet, we find it abhorrent that systems to which we have dedicated our work continue to profit from the hate and disinformation that harms so many of these same workers. (3), (4), (5), (6), (7), (8). Online misinformation can have real and dire consequences offline, ranging from targeted violence to vaccine hesitancy. Misinformation on Alphabet products facilitates the proliferation of hate-filled conspiracy theories, like QAnon, which has repeatedly lead to incidents of targeted violence and been deemed a domestic terror threat by the FBI. Beyond physical violence, the spread of conspiracy theories and misinformation online contributes to diffuse harms that affect those across the US and abroad, such as public health violations, lower vaccination rates, and decreased democratic participation. -

Proposal Educational School Supplies

Solicitation 19-05 REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL EDUCATIONAL SCHOOL SUPPLIES Proposal Office Depot Proposal Region 4 ESC Solicitation 19-05 for Educational School Supplies Texas Regional Print Facility 2230 North Highway 360 Grand Prairie, TX 75050 Our dedicated team of Texas-based print professionals is proud to prepare this proposal to Region 4 ESC’s Evaluation Team for review. Educational School Supplies 19‐05 January 22, 2019 Region 4 Education Service Center 7145 West Tidwell Road Houston, TX 77095 Dear Region 4 ESC Review Committee: We appreciate the opportunity to present you with our comprehensive proposal to Solicitation 19‐05 for Educational School Supplies. Our team has prepared a complete package that will demonstrate our capabilities to provide School Supplies to Region 4 ESC & participating public agencies with unparalleled service, expertise, and unprecedented value and savings. Our team believes our RFP response demonstrates our passion for your business, our enthusiasm to understand and exceed your expectations, and our desire to present a sustainable offer that will allow for the success and growth of all parties. New contract innovations include: Expanded Educational Solutions & Capabilities Increased School Core list by over 1000 items from our current contract offering Innovation pricing strategies to align with the shift in public procurement trends Customizable Core list capabilities for meaningful added values Enhanced Rebate Incentives For more than 30 years Office Depot has been committed to our customers by providing best‐in‐class products and services. Our collective team is dedicated and aligned to the success of Region 4 ESC and all the agencies associated with this contract.