Washington State 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Periodically Spaced Anticlines of the Columbia Plateau

Geological Society of America Special Paper 239 1989 Periodically spaced anticlines of the Columbia Plateau Thomas R. Watters Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C. 20560 ABSTRACT Deformation of the continental flood-basalt in the westernmost portion of the Columbia Plateau has resulted in regularly spaced anticlinal ridges. The periodic nature of the anticlines is characterized by dividing the Yakima fold belt into three domains on the basis of spacings and orientations: (1) the northern domain, made up of the eastern segments of Umtanum Ridge, the Saddle Mountains, and the Frenchman Hills; (2) the central domain, made up of segments of Rattlesnake Ridge, the eastern segments of Horse Heaven Hills, Yakima Ridge, the western segments of Umtanum Ridge, Cleman Mountain, Bethel Ridge, and Manastash Ridge; and (3) the southern domain, made up of Gordon Ridge, the Columbia Hills, the western segment of Horse Heaven Hills, Toppenish Ridge, and Ahtanum Ridge. The northern, central, and southern domains have mean spacings of 19.6,11.6, and 27.6 km, respectively, with a total range of 4 to 36 km and a mean of 20.4 km (n = 203). The basalts are modeled as a multilayer of thin linear elastic plates with frictionless contacts, resting on a mechanically weak elastic substrate of finite thickness, that has buckled at a critical wavelength of folding. Free slip between layers is assumed, based on the presence of thin sedimentary interbeds in the Grande Ronde Basalt separating groups of flows with an average thickness of roughly 280 m. -

HFE Core Sell Sheet Pdf 1.832 MB

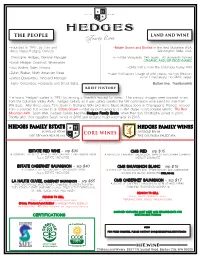

TRADE MARK THE PEOPLE LAND AND WINE amily state -Founded in 1987, by Tom and -Estate Grown and Bottled in the Red Mountain AVA, Anne-Marie Hedges, Owners Washington State, USA. -Christophe Hedges, General Manager -5 Estate Vineyards. 145 acres. All vineyards farmed ORGANIC AND/OR BIODYNAMIC -Sarah Hedges Goedhart, Winemaker -Boo Walker, Sales Director -CMS fruit is from the Columbia Valley AVA -Dylan Walker, North American Sales -Estate Vinification: Usage of wild yeasts, no/min filtration, -James Bukavinsky, Vineyard Manager sulfur if neccesary, no GMO, vegan -Kathy Cortembos, Hospitality and Direct Sales -Bottom line: Traditionalists BRIEF HISTORY The brand ‘Hedges’ started in 1987 by winning a Swedish request for wines. The primary vintages were sourced wines from the Columbia Valley AVA. Hedges Cellars, as it was called, created the first commerical wine blend for sale from WA State. After three years, Tom (born in Richland, WA) and Anne-Marie Hedges (born in Champagne, France), moved from a sourced fruit model to an Estate Grown model, by purchasing land in WA States’ most coveted terroir: The Red Mountain AVA. Soon after, Hedges Cellars became Hedges Family Estate, when their son Christophe joined in 2001. Shortly after, their daughter Sarah joined in 2006 and became head winemaker in 2015. HEDGES FAMILY ESTATE HEDGES FAMILY WINES SOURCED FROM SOURCED FROM THE RED MOUNTAIN AVA CORE WINES THE COLUMBIA VALLEY AVA ESTATE RED WINE - srp $30 CMS RED - srp $15 A DOMINATE BLEND OF MERLOT AND CABERNET SAUVIGNON FROM A BLEND OF CABERNET SAUVIGNON, MERLOT AND SYRAH CURRENT ALL 5 ESTATE VINEYARDS. MERLOT DOMINATE ESTATE CABERNET SAUVIGNON - srp $40 CMS SAUVIGNON BLANC - srp $15 A DOMINATE BLEND CABERNET SAUVIGNON FROM A BLEND OF SAUVIGNON BLANC, CHARDONNAY AND MARSANNE. -

Pinotfile Vol 9 Issue 39

If you drink no Noir, you Pinot Noir Volume 9, Issue 39 March 31, 2014 Adventures on the Pinot Trail: World of Pinot Noir - The Seminars On February 27, 2014, I hit the Pinot Trail to attend four major events in California. Like the song, “Sugartime,” from the 1950s sung by the McGuire Sisters, it was “Sugar (Pinot) in the morning, Sugar (Pinot) in the evening, Sugar (Pinot) at suppertime. Be my little sugar, And love me (Pinot) all the time.” The trail first led me to Santa Barbara for the 14th Annual World of Pinot Noir, then to San Francisco for three more memorable events: a special retrospective tasting of the wines of Ted Lemon titled “30 Years of Winemaking, 20 years of Littorai,” at Jardiniere restaurant on March 2, Affairs of the Vine Pinot Noir Summit at The Golden Gate Club on March 9, and the In Pursuit of Balance seminars and tasting at Bluxome Street Winery on March 10. I will give a full report on each stop along the Pinot Trail in this issue and those to follow, highlighting some of the special wines I tasted. Some have accused me of being a Pinot pimp and rightfully so. One of my readers told me when I asked him what he had been drinking, “As far as what I am drinking, it’s Pinot you bastard, and it’s your damn fault. Now I empty my bank account at wineries nobody has ever heard of, on wines nobody has ever drank except you, you pr**k. You have ruined me....and I love it.” The World of Pinot Noir successfully relocated this year from its long-standing home in Shell Beach to the Bacara Resort & Spa in Santa Barbara. -

1989 International Pinot Noir Celebration Program

Linfield University DigitalCommons@Linfield Willamette Valley Archival Documents - IPNC 1989 1989 International Pinot Noir Celebration Program International Pinot Noir Celebration Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/ipnc_docs Part of the Viticulture and Oenology Commons Recommended Citation International Pinot Noir Celebration, "1989 International Pinot Noir Celebration Program" (1989). Willamette Valley Archival Documents - IPNC. Program. Submission 2. https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/ipnc_docs/2 This Program is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It is brought to you for free via open access, courtesy of DigitalCommons@Linfield, with permission from the rights-holder(s). Your use of this Program must comply with the Terms of Use for material posted in DigitalCommons@Linfield, or with other stated terms (such as a Creative Commons license) indicated in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, or if you have questions about permitted uses, please contact [email protected]. PROGRAM The Third Annual International Pinot Noir Celebration McMinnville, Oregon Index WELCOME .............................. 11 PROGRAM Friday ............................... iii Saturday ............................ v Sunday ............................. viii HONORED GUESTS Speakers and Panelists .................2 Chefs ................................8 ... Musicians ............................9 WINE PRODUCERS Australia ............................11 California ............................12 -

Pinotfile Vol 7 Issue 22

It’s the Place, Stupid! Volume 7, Issue 22 August 4, 2009 Papa Pinot’s Legacy Pervades 2009 IPNC “David Lett defined the term “visionary,” sailing against a strong current as he fulfilled the promise of Oregon wine. He planted grapes where others deemed it impossible, understanding that the very finest wines are often grown where it is most perilous, and he thrived on that challenge. His personality set the tone for the character of the Oregon wine industry, and his stunning wines rewarded his fearlessness, focus and independence. For those who prefer their opinions strong and their wines elegant, David was your man. What an inspiration.” Ted Farthing, Oregon Wine Board Executive Director, Oregon Wine Press, January 2009 Each July for the past twenty-four years, McMinnville, Oregon, has become Beaune in the USA. 700 Pinot geeks from all over the country and from every corner of the world descend on this inauspicious town to celebrate the fickle darling of wine cognoscenti and revel in their indulgence. The International Pinot Noir Celebration (IPNC) is held on the intimate and bucolic campus of Linfield College, but there is no homework or written tests, and no dreadful lectures at 8:00 in the morning, just an abundance of great Pinot Noir paired with the delicious bounty of Oregon prepared by the Pacific Northwest’s most talented chefs, and plenty of joie de vivre. This year’s IPNC, held on July 24-26, 2009, marked the twenty-third event, dating back to 1987, when a group of grape farmers and winemakers assembled to figure out a way to promote Oregon wine. -

2015 Readers Merlot

1RDRS5 20 READERS MERLOT 15 COLUMBIA VALLEY A.V.A. n outstanding Merlot from Washington’s revered old vineyards Conner Lee and Dionysus. Our Readers blend tips its hat to all exploratory readers of books and wine. Blending Conner Lee Vineyard’s 1992 old block Merlot and Dionysus Vineyards’ block A15 Merlot combines two super character vineyards. Elephant Mountain Vineyard’s Cabernet bring spice and complexity to the blend. This powerful wine offers fragrant cherries and chocolate with rich marrionberry flavors in this delicious easy drinking style. VINTAGE Vintage 2015 is Washington’s leading hot vintage and earliest ripening harvest. Our vineyards yielded fruit with record color and tannin. This is in alignment with our house style of rich and smooth age-worthy reds. Spring broke buds in March and flowered in May, setting the stage for the early harvest. Late spring developed small grapes on small clusters in all our vineyards. Summer temperatures were hotter than average and lead to an early July verasion. Together early and swift verasion are hallmarks of great vintages. Our fruit we shaded with healthy canopies balancing acidity and sugar ripeness while protecting against sunburn. We harvested summer fruits in excellent condition. WINEMAKING Dionysus we harvested August 26 into small fermenters. Conner Lee Vineyard we picked at the peak of ripeness swiftly by Pellenc Selective harvester September 10 delivering perfectly sorted fruit right on time. We hand mixed for two weeks, then finished fermentation in barrels and puncheons. We aged on lees reductively, developing savory tones complimentary to the powerful fruit. After 20 months, we selected the final blend. -

Columbia Valley AVA Willard Vineyard

2020 Division-Villages “l’Isle Verte” Chenin Blanc Columbia Valley AVA Willard Vineyard One of the fastest growing and diverse American wine growing regions of the past 40 years is the Columbia Valley, a wide swath of land that reaches from the northern border of Oregon to well into the northeastern parts of Washington State. Within this region is a is the Yakima Valley, home to our old vine Chenin Blanc at Willard Farms. This Chenin vineyard has over 45 years of own-rooted development at the highest elevation in the north central Yakima, which helps insulate the vines from the year to year climate variation. The Willard Chenin vines are planted on soils formed from volcanic Miocene uplift against basalt bedrock with the primary topsoil being made up of quartz and lime silica, overlaid with the mixed glacial sedimentary runoff of Missoula floods that makes the soils in the region so dynamic and unique. We adore this particular site, as it is one of the last remaining old vine Chenin Blanc sites in the Pacific Northwest, has demonstrated a unique and interesting terroir influence in the wines, and is farmed by an excellent, albeit quirky, farmer named Jim Willard who has a deep understanding of the soils and region. The 2020 vintage created some unique challenges for the entire West Coast, most notably the wildfires that plagued Oregon and California. Thankfully, Willard Farms and the Columbia Valley was spared from the fires and experienced mostly only high level haze. However, poor yields, like Oregon, were the norm in the Columbia Valley too from a poor fruit set during the flowering in June. -

1000 Best Wine Secrets Contains All the Information Novice and Experienced Wine Drinkers Need to Feel at Home Best in Any Restaurant, Home Or Vineyard

1000bestwine_fullcover 9/5/06 3:11 PM Page 1 1000 THE ESSENTIAL 1000 GUIDE FOR WINE LOVERS 10001000 Are you unsure about the appropriate way to taste wine at a restaurant? Or confused about which wine to order with best catfish? 1000 Best Wine Secrets contains all the information novice and experienced wine drinkers need to feel at home best in any restaurant, home or vineyard. wine An essential addition to any wine lover’s shelf! wine SECRETS INCLUDE: * Buying the perfect bottle of wine * Serving wine like a pro secrets * Wine tips from around the globe Become a Wine Connoisseur * Choosing the right bottle of wine for any occasion * Secrets to buying great wine secrets * Detecting faulty wine and sending it back * Insider secrets about * Understanding wine labels wines from around the world If you are tired of not know- * Serve and taste wine is a wine writer Carolyn Hammond ing the proper wine etiquette, like a pro and founder of the Wine Tribune. 1000 Best Wine Secrets is the She holds a diploma in Wine and * Pairing food and wine Spirits from the internationally rec- only book you will need to ognized Wine and Spirit Education become a wine connoisseur. Trust. As well as her expertise as a wine professional, Ms. Hammond is a seasoned journalist who has written for a number of major daily Cookbooks/ newspapers. She has contributed Bartending $12.95 U.S. UPC to Decanter, Decanter.com and $16.95 CAN Wine & Spirit International. hammond ISBN-13: 978-1-4022-0808-9 ISBN-10: 1-4022-0808-1 Carolyn EAN www.sourcebooks.com Hammond 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page i 1000 Best Wine Secrets 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page ii 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page iii 1000 Best Wine Secrets CAROLYN HAMMOND 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page iv Copyright © 2006 by Carolyn Hammond Cover and internal design © 2006 by Sourcebooks, Inc. -

CSW Work Book 2021 Answer

Answer Key Key Answer Answer Key Certified Specialist of Wine Workbook To Accompany the 2021 CSW Study Guide Chapter 1: Wine Composition and Chemistry Exercise 1: Wine Components: Matching 1. Tartaric Acid 6. Glycerol 2. Water 7. Malic Acid 3. Legs 8. Lactic Acid 4. Citric Acid 9. Succinic Acid 5. Ethyl Alcohol 10. Acetic Acid Exercise 2: Wine Components: Fill in the Blank/Short Answer 1. Tartaric Acid, Malic Acid, Citric Acid, and Succinic Acid 2. Citric Acid, Succinic Acid 3. Tartaric Acid 4. Malolactic Fermentation 5. TA (Total Acidity) 6. The combined chemical strength of all acids present 7. 2.9 (considering the normal range of wine pH ranges from 2.9 – 3.9) 8. 3.9 (considering the normal range of wine pH ranges from 2.9 – 3.9) 9. Glucose and Fructose 10. Dry Exercise 3: Phenolic Compounds and Other Components: Matching 1. Flavonols 7. Tannins 2. Vanillin 8. Esters 3. Resveratrol 9. Sediment 4. Ethyl Acetate 10. Sulfur 5. Acetaldehyde 11. Aldehydes 6. Anthocyanins 12. Carbon Dioxide Exercise 4: Phenolic Compounds and Other Components: True or False 1. False 7. True 2. True 8. False 3. True 9. False 4. True 10. True 5. False 11. False 6. True 12. False Chapter 1 Checkpoint Quiz 1. C 6. C 2. B 7. B 3. D 8. A 4. C 9. D 5. A 10. C Chapter 2: Wine Faults Exercise 1: Wine Faults: Matching 1. Bacteria 6. Bacteria 2. Yeast 7. Bacteria 3. Oxidation 8. Oxidation 4. Sulfur Compounds 9. Yeast 5. Mold 10. Bacteria Exercise 2: Wine Faults and Off-Odors: Fill in the Blank/Short Answer 1. -

Washington Vineyard Acreage Report 2017

Washington Vineyard Acreage Report 2017 Posted Online November 8, 2017 Washington Vineyard Acreage Report, 2017 Compiled by USDA/NATIONAL AGRICULTURAL STATISTICS SERVICE Northwest Regional Field Office Chris Mertz, Director Dennis Koong, Deputy Director Steve Anderson, Deputy Director P. O. Box 609 Olympia, Washington 98507 Phone: (360) 890-3300 Fax: (855) 270-2721 e-mail: [email protected] U.S. Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Statistics Service Hubert Hamer, Administrator The funds for this work came from a Washington State Department of Agriculture Specialty Crop Block Grant Program awarded to the Washington State Tree Fruit Association. Other Northwest collaborators include: Washington Wine Commission, Washington State Fruit Commission, and Washington Winegrowers. USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer 2 Washington Vineyard Acreage Report 2017 USDA, National Agricultural Statistics Service - Northwest Regional Field Office Table of Contents Overview Office Staff and Credits ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Wine AVA Map ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Notes about the data ................................................................................................................................................ 5-6 Wine Grapes Acreage by Variety, Historic Comparisons -

JWE 10 3 Bookreviews 382..384

382 Book and Film Reviews VIVIAN PERRY and JOHN VINCENT: Winemakers of the Willamette Valley: Pioneering Vintners from Oregon’s Wine Country. American Palate, Charleston, South Carolina, 2013, 160 pp., ISBN: 978-1609496760 (paperback), $19.99. CILA WARNCKE: Oregon Wine Pioneers. Vine Lives Publishing, Portland, Oregon, 2015, 234 pp., ISBN: 978-1943090761 (paperback), $19.99. Admittedly, it was hard to write a dispassionate review of books that so lovingly describe the region in which I live and so admiringly profile many of my acquain- tances in the Oregon wine industry. Therefore, I used as measures of merit how well each echoed my impressions of this most beautiful area and its people, and whether each accomplished its objectives. Perry’s and Vincent’s Winemakers of the Willamette Valley (WWV) “is meant to showcase the stories of a handful of Oregon’s many Willamette Valley winemakers” (WWV, p. 11). A foreword by Chehalem founder Harry Peterson-Nedry sets the per- sonal tone that pervades those stories. Next, in a mere eight pages of text, the first chapter, “History of the Willamette Valley Wine Region,” covers the climate, soil, grape selection, craftsmanship, industry structure and early success in sufficient detail to provide valuable context. The authors then share intimate interviews with eighteen vintners and vignerons. Within each chapter named for one or two wine- makers are brief descriptions of the wineries that each is affiliated with. These include year founded, ownership, varietals, tasting room location, hours and con- tacts. Sustainability features, a point of pride in the Oregon wine industry, are also listed. -

SERIES Even Thousands of Years to Define, Winery

GEOSCIENCE CANADA Volume 31 Number 4 December 2004 167 SERIES even thousands of years to define, winery. The quality of the grape, develop, and understand their best however, is the result of the combination terroir, newer regions typically face a of five main factors: the climate, the site trial and error stage of finding the best or local topography, the nature of the variety and terroir match. This research geology and soil, the choice of the grape facilitates the process by modeling the variety, and how they are together climate and landscape in a relatively managed to produce the best crop young grape growing region in Oregon, (Fig. 1). The French have named this the Umpqua Valley appellation. The interaction between cultural practices, result is an inventory of land suitability the local environment, and the vines, the that provides both existing and new “terroir.” While there will always be growers greater insight into the best some disagreement over which aspects Geology and Wine 8. terroirs of the region. of the terroir are most influential, it is Modeling Viticultural clear that the prudent grape grower must Landscapes: A GIS SOMMAIRE understand their interactions and Le terroir est un concept holiste de controls on grape growth and quality (for Analysis of the Terroir facteurs environnementaux et culturels a good review of the concept of terroir Potential in the Umpqua agissant sur un continuum s’étendant de see Vaudour, 2002). Valley of Oregon la croissance de la vigne à la vinification. Numerous researchers have Dans le domaine des facteurs physiques, examined various aspects of terroir at il faut trouver la combinaison idéale different spatial scales providing insights entre la variété du raisin d’une part, et le into the complex inter-relationships Gregory V.