Borgmann: the Man Behind the Legend

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iterations of the Words-To-Numbers Function

1 2 Journal of Integer Sequences, Vol. 21 (2018), 3 Article 18.9.2 47 6 23 11 Iterations of the Words-to-Numbers Function Matthew E. Coppenbarger School of Mathematical Sciences 85 Lomb Memorial Drive Rochester Institute of Technology Rochester, NY 14623-5603 USA [email protected] Abstract The Words-to-Numbers function takes a nonnegative integer and maps it to the number of characters required to spell the number in English. For each k = 0, 1,..., 8, we determine the minimal nonnegative integer n such that the iterates of n converge to the fixed point (through the Words-to-Numbers function) in exactly k iterations. Our travels take us from some simple answers, to an etymology of the names of large numbers, to Conway/Guy’s established system representing the name of any integer, and finally use generating functions to arrive at a very large number. 1 Introduction and initial definitions The idea for the problem originates in a 1965 book [3, p. 243] by recreational linguistics icon Dmitri Borgmann (1927–85) and in a 1966 article [16] by another icon, recreational mathematician Martin Gardner (1914–2010). Gardner’s article appears again in a book [17, pp. 71–72, 265–267] containing reprinted Gardner articles from Scientific American along with his comments on his reader’s responses. Both Borgmann and Gardner identify the only English number that requires exactly the same number of characters to spell the number as the number represents. Borgmann goes further by identifying numbers in 16 other languages with this property. Borgmann calling such numbers truthful and Gardner calling them honest. -

Mathematical Circus & 'Martin Gardner

MARTIN GARDNE MATHEMATICAL ;MATH EMATICAL ASSOCIATION J OF AMERICA MATHEMATICAL CIRCUS & 'MARTIN GARDNER THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Washington, DC 1992 MATHEMATICAL More Puzzles, Games, Paradoxes, and Other Mathematical Entertainments from Scientific American with a Preface by Donald Knuth, A Postscript, from the Author, and a new Bibliography by Mr. Gardner, Thoughts from Readers, and 105 Drawings and Published in the United States of America by The Mathematical Association of America Copyright O 1968,1969,1970,1971,1979,1981,1992by Martin Gardner. All riglhts reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. An MAA Spectrum book This book was updated and revised from the 1981 edition published by Vantage Books, New York. Most of this book originally appeared in slightly different form in Scientific American. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 92-060996 ISBN 0-88385-506-2 Manufactured in the United States of America For Donald E. Knuth, extraordinary mathematician, computer scientist, writer, musician, humorist, recreational math buff, and much more SPECTRUM SERIES Published by THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Committee on Publications ANDREW STERRETT, JR.,Chairman Spectrum Editorial Board ROGER HORN, Chairman SABRA ANDERSON BART BRADEN UNDERWOOD DUDLEY HUGH M. EDGAR JEANNE LADUKE LESTER H. LANGE MARY PARKER MPP.a (@ SPECTRUM Also by Martin Gardner from The Mathematical Association of America 1529 Eighteenth Street, N.W. Washington, D. C. 20036 (202) 387- 5200 Riddles of the Sphinx and Other Mathematical Puzzle Tales Mathematical Carnival Mathematical Magic Show Contents Preface xi .. Introduction Xlll 1. Optical Illusions 3 Answers on page 14 2. Matches 16 Answers on page 27 3. -

Letters in Squares- Word Puzzles in English

UNIVERZA V MARIBORU FILOZOFSKA FAKULTETA ODDELEK ZA ANGLISTIKO IN AMERIKANISTIKO Diplomsko delo LETTERS IN SQUARES- WORD PUZZLES IN ENGLISH Mentorica: Kandidatka: Doc.dr. Katja Plemenitaš Mateja Vinovrški Maribor, 2010 ZAHVALA Hvala vsem, ki ste kakorkoli pomagali, da je ta naloga tukaj! U N I V E R Z A V M A R I B O R U F I L O Z O F S K A F A K U L T E T A Koroška cesta 160 2000 Mariboor IZJAVA O AVTORSTVU Podpisana Mateja Vinovrški, rojena 23. aprila 1980 v Mariboru, študentka Filozofske fakultete Univerze v Mariboru, smer angleški jezik s književnostjo in biologija, izjavljam, da je diplomsko delo z naslovom Črke v kvadratih – besedne uganke v angleščini oz. Letters in squares – Word puzzles in English pri mentorici doc. dr. Katji Plemenitaš, avtorsko delo. V diplomskem delu so uporabljeni viri in literatura korektno navedeni; teksti niso prepisani brez navedbe avtorjev. ABSTRACT Word puzzles and games are an important tool for learning and consolidating language. They appear in various forms and in various media (books, online, board games and newspapers). This diploma thesis presents the history of word puzzles and offers a classification of different types of word puzzles and games. In order to gauge how English language-learning materials in Slovenia utilize word puzzles, an analysis of the number of occurrences and variety of word puzzles in English language study books that are offered in Slovenia is also presented. A survey among Slovenian primary school learners has been made regarding the use of crosswords in the classroom and its results are also presented. -

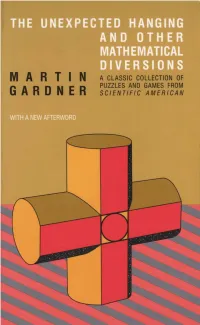

The Unexpected Hanging and Other Mathematical Diversions

AND OTHER MATHEMATICAL nIVERSIONS OLLECTION OF GI ES FRON A ERIC" The Unexpected Hanging A Partial List of Books by Martin Gardner: The Annotated "Casey at the Bat" (ed.) The Annotated Innocence of Father Brown (ed.) Hexaflexagons and Other Mathematical Diversions Logic Machines and Diagrams The Magic Numbers of Dr. Matrix Martin Gardner's Whys and Wherefores New Ambidextrous Universe The No-sided Professor Order and Surprise Puzzles from Other Worlds The Sacred Beetle and Other Essays in Science (ed.) The Second Scientific American Book of Mathematical Puzzles and Diversions Wheels, Life, and Other Mathematical Entertainments The Whys of a Philosopher Scrivener MARTIN GARDNER The Unexpected Hanging And Other Mathematical Diversions With a new Afterword and expanded Bibliography The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London Material previously published in Scientific American is copyright 0 1961, 1962, 1963 by Scientific American, Inc. All rights reserved. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London O 1969, 1991 by Martin Gardner All rights reserved. Originally published 1969. University of Chicago Press edition 1991 Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gardner, Martin, 1914- The unexpected hanging and other mathematical diversions : with a new afterword and expanded bibliography 1 Martin Gardner. - University of Chicago Press ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-226-28256-2 (pbk.) 1. Mathematical recreations. I. Title. QA95.G33 1991 793.7'4-dc20 91-17723 CIP @ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI 239.48-1984. -

Martin Gardner Papers SC0647

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6s20356s No online items Guide to the Martin Gardner Papers SC0647 Daniel Hartwig & Jenny Johnson Department of Special Collections and University Archives October 2008 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Note This encoded finding aid is compliant with Stanford EAD Best Practice Guidelines, Version 1.0. Guide to the Martin Gardner SC064712473 1 Papers SC0647 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Martin Gardner papers Creator: Gardner, Martin Identifier/Call Number: SC0647 Identifier/Call Number: 12473 Physical Description: 63.5 Linear Feet Date (inclusive): 1957-1997 Abstract: These papers pertain to his interest in mathematics and consist of files relating to his SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN mathematical games column (1957-1986) and subject files on recreational mathematics. Papers include correspondence, notes, clippings, and articles, with some examples of puzzle toys. Correspondents include Dmitri A. Borgmann, John H. Conway, H. S. M Coxeter, Persi Diaconis, Solomon W Golomb, Richard K.Guy, David A. Klarner, Donald Ervin Knuth, Harry Lindgren, Doris Schattschneider, Jerry Slocum, Charles W.Trigg, Stanislaw M. Ulam, and Samuel Yates. Immediate Source of Acquisition note Gift of Martin Gardner, 2002. Information about Access This collection is open for research. Ownership & Copyright All requests to reproduce, publish, quote from, or otherwise use collection materials must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, California 94304-6064. Consent is given on behalf of Special Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission from the copyright owner. -

Logological Poetry: an Editorial

3 log%gica/ Poetry AN EDITORIAL It was Dmitri Borgmann who put the word "logology" into circulation. Before Langu.age on Vacation, his first book, was published, he wrote to me: "I don't believe the word 'IogoIogy' has ever appeared in a book devoted to words or puzzles. I dug it out of the unabridged Oxford while searching for a suitable name for my activity." He then gave the following information: None of the unabridged Funk and Wagnall's contain LOGOLOGY. Webster's Second and Third Editions do not contain LOGOLOGY. Webster's First Edition gives it as a synonym for "philology," which IS some thing else. The Century Dictionary and The New Century Dictionary do not contain the word. The Century Dictionary Supplement (2 volumes, 1909), defines it as the doc trine of the Logos (in theology). The unabridged Oxford gives two definitions: (I) The doctrine of the Logos (only as the title of two books in the 18th century) ; and (2) The science of words (rare-illustrated by two quotations, both from magazines dated 1820 and 1878). Mr. Borgmann was looking for a word which was not already c1aimed as the sole property of any other type of word expert. The commonly used tenn "word play" has about it an objectionably trifling aura. Not much sense of doing things with a vengeance exudes from its weak semantic fabric. Probably the haH-forgotten wore!, "logology," had dwelt long enough in limbo awaiting a new cause to serve. Several years ago I wished to acquire a list of all kno'wn word transpositions. -

Time Travel and Other Mathematical Bewilderments Time Travel

TIME TRAVEL AND OTHER MATHEMATICAL BEWILDERMENTS TIME TRAVEL AND OTHER MATHEMATICAL BEWILDERMENTS MARTIN GARDNER me W. H. FREEMAN AND COMPANY NEW YORK Library of'Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Gardner, Martin, 1914- Time travel and other mathematical bewilderments. 1nclud~:s index. 1. Mathematical recreations. I. Title. QA95.G325 1987 793.7'4 87-11849 ISBN 0-7167-1924-X ISBN 0-7167-1925-8 @bk.) Copyright la1988 by W. H. Freeman and Company No part of this book may be reproduced by any mechanical, photographic, or electronic process, or in the form of a photographic recording, nor may it be stored in a retrieval system, transmitted, or otherwise copied for public or private use, without written permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America 34567890 VB 654321089 To David A. Klarner for his many splendid contributions to recreational mathematics, for his friendship over the years, and in !gratitude for many other things. CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE Time Travel 1 CHAPTER TWO Hexes. and Stars 15 CHAPTER THREE Tangrams, Part 1 27 CHAPTER FOUR Tangrams, Part 2 39 CHAPTER FIVE Nontransitive Paradoxes 55 CHAPTER SIX Combinatorial Card Problems 71 CHAPTER SEVEN Melody-Making Machines 85 CHAPTER EIGHT Anamorphic. Art 97 CHAPTER NINE The Rubber Rope and Other Problems 11 1 viii CONTENTS CHAPTER TEN Six Sensational Discoveries 125 CHAPTER ELEVEN The Csaszar Polyhedron 139 CHAPTER TWELVE Dodgem and Other Simple Games 153 CHAPTER THIRTEEN Tiling with Convex Polygons 163 CHAPTER FOURTEEN Tiling with Polyominoes, Polyiamonds, and Polyhexes 177 CHAPTER FIFTEEN Curious Maps 189 CHAPTER SIXTEEN The Sixth Symbol and Other Problems 205 CHAPTER SEVENTEEN Magic Squares and Cubes 213 CHAPTER EIGHTEEN Block Packing 227 CHAPTER NINETEEN Induction and ~robabilit~ 24 1 CONTENTS ix CHAPTER TWENTY Catalan Numbers 253 CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE Fun with a Pocket Calculator 267 CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO Tree-Plant Problems 22 7 INDEX OF NAMES 291 Herewith the twelfth collection of my columns from Scientijic American. -

A Recreational Linguistics Library

131 A RECREATIONAL LINGUISTICS LIBRARY DAVID MORICE Iowa City, Iowa The following article is adapted from a paper presented to the class "Foundations and Collections Development" in the University of Io\,<ra's School of Library and Information Sciences. The pro fessor, Gerald Hodges, commented on it in part: "It appears to me that you have done the unthinkable - build an enjoyable and entertaining collection for an academic setting... I do feel that your selection process was systematic, and I think you are on solid ground in going with those titles wh ich had mul tiple favorable reviews. Your annotations not only tell me suf ficient information about each title but do indeed justify the selection decision. The use of a variety of sources, including both library and subject specialization, is a real advantage of the process you used... I particularly want to commend you on the four criteria statements you made and upon the decision to exclude certain formats ...Aren 't you glad that you had some what unlimited budgetary possibilities?" SUBJECT AREA Recreational Linguistics, also known as Logology and Wordplay. THE LIBRARY AND ITS USERS The hypothetical site for this project is an English Department Library at a large university. The library has several thousand volumes covering almost all areas and eras of English literature and language. It subscribes to forty literary periodicals, and its media room houses over a hundred films and fi lmstrips. The pri mary users are undergraduate English majors and graduate students in English and in Linguistics. To a lesser extent, users a Iso in clude students in Education, Modern Language, and Comparative Literature, and, on occasion, non-university members of the commu nity. -

Martin Gardner's New Mathematical Diversions

SPHERE PACKING, LEWIS CARROLL, AND REVERSI For 25 of his 94 years, Martin Gardner wrote “Mathematical Games and Recreations,” a monthly column for Scientific American magazine. These columns have inspired hundreds of thousands of readers to delve more deeply into the large world of math- ematics. He has also made significant contributions to magic, philosophy, children’s literature, and the debunk- ing of pseudoscience. He has produced more than 60 books, including many best sellers, most of which are still in print. His Annotated Alice has sold more than one million copies. He continues to write a regular column for the Skeptical Inquirer magazine. THE NEW MARTIN GARDNER MATHEMATICAL LIBRARY Editorial Board Donald J. Albers, Santa Clara University Gerald L. Alexanderson, Santa Clara University John H. Conway, F.R. S., Princeton University Richard K. Guy, University of Calgary Harold R. Jacobs, U.S. Grant High School, Van Nuys Donald E. Knuth, Stanford University Peter L. Renz, Mathematical Association of America From 1957 through 1986, Martin Gardner wrote the “Mathematical Games” columns for Scientific American that are the basis for these books. Scientific American editor Dennis Flanagan noted that this col- umn contributed substantially to the success of the magazine. The exchanges between Martin Gardner and his readers gave life to these columns and books. These exchanges have continued, and the impact of the columns and books has grown. These new editions give Mar- tin Gardner the chance to bring readers up to date on newer twists on old puzzles and games, on new explanations and proofs, and on links to recent developments and discoveries. -

Omni Magazine

SPECIAL ANNIVE onnrui VOL. 9 NO. 1 EDITOR IN CHIEF & DESIGN DIRECTOR: BOB GUCCIONE PRESIDENT: KATHY KEETON EDITOR: PATRICE ADCROFT GRAPHICS DIRECTOR: FRANK DEVINO EDITOR AT LARGE: DICK TERESI MANAGING EDITOR: STEVE FOX ART DIRECTOR: AMY SEISSLER CONTENTS PAGE OMNIBUS Contributors 10 COMMUNICATIONS Correspondence 14 SPACE Nuclear Reactors Paul Bagne 22 BOOKS Olive Barker Profile Murray Cox 26 STARS Astronomers versus Owen Davies 42 Environmentalists BODY Mind Scan Stephen Robinett 44 EXPLORATIONS Mechanical Zoo Erik Larson 48 LONGEVITY REPORT FIRST WORD Aging Research Kathy Keeton 6 FORUM Bionic Man - Pierre Galletti and 18 Roberl Jarvik. M.D.'s ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE S-jroqate Brains Gram F|ermedal 3B CONTINUUM Life Extenders 51 ELIXIRS OF YOUTH Born-again Genes Ann Giudici Fettner and 60 and Youth Pills Pamela Weintraub BODYSHOP Laser Face-lifts Viva 68 DEATH AVENGERS Immorality Seekers Kaihar ne Lowry 64 LIFELINES Pictorial: Susan Ellis 91 How Man Ages RICHARD CUTLER Interview Pamela Weintraub 108 SOULS ON ICE Cryogenics Psm' Bagne and 116 Nancy Lucas SENTRIES Pictorial Leah Waliach 122 LAST WORD Humor Terry Runte 186 THE END OF THE WHOLE MESS Fiction Stephen King 72 DAYS OF FUTURE PAST P-c:orial. Space Art Ron Miller 76 PIG THIEVES ON PTOLEMY Fiction Leo Daugherty 100 ANTIMATTER UFOs, etc. 131 STAR TECH Tools for Ihe Year 2C0i 167 TRIP TO THE STARS The Great Moon Douglas Colligan 170 Buggy Contest GAMES Wordplay Scot Morris 182 This month's cover is Japanese artist Sachio Yoshida's version o! Sandro Botticelli's famous painting The Birth of Venus. Through the efforts of i. -

COLLOQUY T Is Possible :Onditions Of

149 for example COLLOQUY t is possible :onditions of yth ync Webster's Dictionary defines colloquy as mutual discourse. Read ers are encouraged to submit additions, corrections, and comments about earlier articles appearmg in Word Ways. Comments received at least one month prior to publication of an Issue will appear m that issue. DY, GO, GY, VY, WU, WY, Tributes to the late Dmitri Borgmann continue to arrive. Philip Cohen: February was a fine swan song for Borgmann; it displ ayed his strength s (imagination, indefatigability and range) 19 the Pocket and downplayed what I consider his weaknesses. Whatever nega tive things I've said in the past, I have to agree we've lost e comprehen one of the very greatest. of three-let Harry Partridge: The news about Dmitri Borgmann was dreadful s of the Ox and devastating. You cite Willard Espy as commenting "He was the most dif obviously a difficult man", but one would never know it from his writings, which have always impressed me as uniformly good-hu mored and vivacious ... [a] dense and pregnant style. epared using Darryl Francis: My feelings were echoed by Jeff Grant's words in :ely that the May... Dmitri. .. introduced me to the world of logology [in Language the various nputer might on Vacation]. I can remember the time when I received 6 or 7 letters a day from Dmitri, usually when he was working on a 3ts automa ti prOject that he was particularly enthusiastic a bout. .. Al as! No other individual has so altered my life, except I suppose for my parents, my wife, my kids! The Word Wurcher passed along a n umber of comments on the Borg 's the years mann memorial issue. -

Dmitri Borgmann's Rotas Square Articles

Dmitri Borgmann’s rotas square articles Tristan Miller∗ Austrian Research Institute for Artificial Intelligence Freyung 6/6, 1010 Vienna, Austria [email protected] The rotas square (or alternatively, sator square) is Vacation, 1965; Beyond Language, 1967) and former a Latin palindromic word square, known from various editor of Word Ways (1968). While they attracted little medieval and ancient inscriptions: attention at the time, some 35 years after their publication ROTASSATOR (and 29 years after Borgmann’s death), questions began to be raised about their true authorship. OPERAAREPO The articles contain much internal evidence that, taken together, compellingly supports the notion that T E N E T or T E N E T Borgmann was not their author. First, their subject mat- AREPOOPERA ter is uncharacteristic of Borgmann, who had a keen interest in single-word palindromes, but not sentence- SATORROTAS level palindromes as in the rotas square. Second, several passages in the articles mark them as being addressed The history and precise meaning of the palindrome to a British rather than American audience. For in- has been a perennial subject of discussion in Notes & stance, one paragraph opens with the observation that Queries1 and other venues, both popular and scholarly. both ‘British and American’ writers have been instru- Among these other venues is Word Ways, the American mental in composing and popularizing palindromes, but journal of recreational linguistics, now in its 53rd year. then goes on to discuss only ‘the most important Brit- In 1979 and 1980, Word Ways printed a series of articles ish practitioners’ (emphasis mine). The articles also on the early history, religious symbolism, and cultural occasionally, but not consistently, use Commonwealth significance of the rotas square and other palindromes:2 spellings (‘behaviour’, ‘cancelling’, etc.), suggesting that D.