Mark Gregory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War and Colonial Identity: the Poetic Response

Kunapipi Volume 18 Issue 2 Article 3 1996 War and Colonial Identity: The Poetic Response Michael Ackland Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Ackland, Michael, War and Colonial Identity: The Poetic Response, Kunapipi, 18(2), 1996. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol18/iss2/3 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] War and Colonial Identity: The Poetic Response Abstract For a country spared the ravages of major wars, at least until the twentieth century, Australian creative works preceding federation exhibit a striking concern with martial prowess and the reality or possibility of physical conflict. 131oody encounters with blacks, convicts and bush-rangers frequently provide novelists with dramatic climaxes. Images of the settler literally battling natural d1sasters such as floods and fires. or of the man on horseback performing heroic deeds are iterated in the verse, while such scenes dominate the sprawling historical canvases of the period. Moreover, the spectre of armed struggle appears repeatedly in the political literature of the colonies, either as an Old World horror to be avoided or as a sacrifice willingly accepted for a free and democratic society. Henry Lawson for instance, at the turn of the century, evoked the famous patriot-image of blood staining the wattle, much as forty years before similar concepts -

Australian Poems You NEED to KNOW

1OO Australian Poems You NEED TO KNOW Edited by Jamie Grant Foreword by Phillip Adams hardiegrant books MELBOURNE-LONDON Convict and Stockrider A Convict's Tour to Hell Francis Macnamara ('Frank the Poet') 16 The Beautiful Squatter Charles Harpur 22 Taking the Census Charles R Thatcher 23 The Sick Stockrider Adam Lindsay Gordon 25 The Red Page My Other Chinee Cook James Brunton Stephens 30 Bell-birds Henry Kendall 32 Are You the Cove? Joseph Furphy ('Tom Collins') 34 How McDougal Topped the Score Thomas E Spencer 35 The Wail of the Waiter Marcus Clarke 38 Where the Pelican Builds Mary Hannay Foott 40 Catching the Coach Alfred T Chandler ('Spinifex') 41 Narcissus and Some Tadpoles Victor J Daley 44 6 i Contents Gundagai to Ironbark Nine Miles from Gundagai Jack Moses 48 The Duke of Buccleuch JA Philp 49 How We Drove the Trotter WTGoodge 50 Our Ancient Ruin 'Crupper D' 52 The Brucedale Scandal Mary Gilmore 53 Since the Country Carried Sheep Harry Morant ('The Breaker') 56 The Man from Ironbark AB Paterson (The Banjo') 58 The Old Whimrhorse Edward Dyson 60 Where the Dead Men Lie Barcroft Boake 62 Australia Bernard O'Dowd , 64 The Stockman's Cheque EW Hornung 65 The Bullocky's Love-episode AF York 67 Bastard and Bushranger «<§!> The Bastard from the Bush Anonymous 70 When your Pants Begin to Go Henry Lawson 72 The Fisher Roderic Quinn 74 The Mystery Man 'NQ' 75 Emus Mary Fullerton 76 The Death of Ben Hall Will H Ogilvie 77 The Coachman's Yarn EJ Brady 80 Fire in the Heavens, and Fire Along the Hills Christopher Brennan 83 The Orange Tree -

HENRY LAWSON WAS HERE Celebrating the Life of a Famous Australian

HENRY LAWSON WAS HERE Celebrating the life of a famous Australian LOWELL TARLING HE WASN’T BORN IN A TENT that blew down in a storm. Contrary to legend there were no thunderclaps and there was no flood on the night of 17 June 1867. On the contrary, it was a calm and frosty night in Grenfell in western New South Wales when Henry Lawson was born in a log cabin that served as a temporary community hospital. Henry’s father, 33 year old Niels Larson, was a Norwegian-born miner. His partner in the One-Mile diggings claim, Wilhelm Slee (later Chief Inspector of Mines for New South Wales), was a member of the Grenfell Hospital committee and not the kind of person who would see his mate’s vulnerable 19 year old girl-wife give birth in a tent. But an older, more famous Henry was happy to go along with the tale that he was welcomed into the world with a torrent of wicked weather. Henry’s parents, Niels Larsen and Louisa Albury, met at the goldfields of Pipeclay (now Eurunderee NSW). They were married at the Wesleyan Parsonage Mudgee, eleven months before Henry was born. On the birth of their first child the family name was Anglicised. Louisa registered Henry as ‘Lawson’ and Niels followed suit, also changing his given name to Peter. Peter Lawson’s tombstone in the Hartley Vale cemetery at the foot of Mount York, bears his original name - Niels Hertzberg Larsen, ‘father of Henry Lawson, Peter, Charles, Gertrude and Henrietta’. Henry may not have been born in a tent, but a sturdy well-reinforced tent was certainly his first home. -

Legislative Council

1236 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Friday 27 May 2011 __________ The President (The Hon. Donald Thomas Harwin) took the chair at 9.30 a.m. The President read the Prayers. LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL VACANCIES Election of Walter Secord and Adam Searle The PRESIDENT: At a joint sitting held on 24 May 2011 Walter Secord was elected to fill the vacancy in the Legislative Council caused by the resignation of the Hon. Edward Moses Obeid, and Adam Searle was elected to fill the vacancy in the Legislative Council caused by the resignation of the Hon. John Hatzistergos. PLEDGE OF LOYALTY The Hon. Walter Secord and the Hon. Adam Searle took and subscribed the pledge of loyalty and signed the roll. STRATEGIC REGIONAL LAND USE POLICY Motion by the Hon. Jeremy Buckingham agreed to: 1. That this House congratulates the Government on its efforts during the election campaign to address the significant impacts of the coal and coal seam gas industries on New South Wales communities by developing its Strategic Regional Land Use Policy. 2. That this House calls on the Government to: (a) Ensure further development of this policy includes the meaningful engagement of affected communities by: (i) recognising and considering the significant amount of work done by individuals and groups in contributing to the Department of Planning Coal and Gas Strategy Process, (ii) starting a public consultation process in the development of a definition of "Strategic Agricultural Land" as it relates to the transition plan, (iii) ensuring that draft Aquifer Interference Regulations are open for public submission before being adopted, and (b) ensure non-agricultural communities and the environment are not left out in any strategy to improve the regulation of the coal and coal seam gas industries. -

George Gordon Mccrae - Poems

Classic Poetry Series George Gordon McCrae - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive George Gordon McCrae(9 May 1833 – 15 August 1927) George Gordon McCrae was an Australian poet. <b>Early life</b> McCrae was born in Leith, Scotland; his father was Andrew Murison McCrae, a writer; his mother was Georgiana McCrae, a painter. George attended a preparatory school in London, and later received lessons from his mother. Georgiana and her four sons emigrated to Melbourne in 1841 following her husband who emigrated in 1839. <b>Career</b> After a few years as a surveyor, McCrae joined the Victorian Government service, eventually becoming Deputy Registrar-General, and also a prominent figure in literary circles. Most of his leisure time was spent in writing. His first published work was Two Old Men's Tales of Love and War (London, 1865). His son <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/hugh-mccrae/">Hugh McCrae</a> also a poet, produced a volume of memoirs (My Father and My Father's Friends) about George and his association with such literary figures as <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/henry-kendall/">Henry Kendall</a>, <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/adam-lindsay-gordon/">Adam Lindsay Gordon</a>, <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/richard-henry- horne/">Richard Henry Horne</a> and <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/marcus-clarke/">Marcus Clarke</a>. George McCrae wrote novels, stories, poetry, and travel sketches, and illustrated books. After his retirement, unpublished manuscripts entitled 'Reminiscences—Experiences not Exploits' contain detailed descriptions of events from his youth and present a record of the early European part of Melbourne country-side. -

Australian Verse

THE NEW OXFORD BOOK OF AUSTRALIAN VERSE Chosen by Les A. Murray Melbourne OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Oxford Auckland New York CONTENTS Foreword xxi Sam Woolagoodjah Lalai (Dreamtime) 1 Barron Field (1786—1846) The Kangaroo 6 Richard Whately (1787-1863) There is a Place in Distant Seas 7 Anonymous A Hot Day in Sydney 8 The Exile of Erin 11 Hey, Boys! Up Go We! 12 The Limejuice Tub 13 John Dunmore Lang (1799-1878) Colonial Nomenclature 14 Anonymous Van Diemen's Land 15 The Convicts' Rum Song 16 Hail South Australia! 16 The Female Transport 17 The Lass in the Female Factory 18 Francis MacNamara (Frank the Poet) (b. 1811?) A petition from the chain gang 19 - For the Company underground 22 A Convict's Tour to Hell 23 Robert Lowe (1811-1892) Songs of the Squatters, I and II 28 Charles Harpur (1813-1868) A Basket of Summer Fruit 31 Wellington 32 A Flight of Wild Ducks 33 Henry Parkes (1815-1896) Our Coming Countrymen 34 Aboriginal Songs from the 1850s Kilaben Bay song (Awabakal) 36 VI CONTENTS Women's rondo (Awabakal) 37 Two tongue-pointing (satirical) songs (Kamilaroi) 38 The drunk man (Wolaroi) 38 Anonymous Whaler's Rhyme 38 The Diggins-oh 39 William W. Coxon (?) The Flash Colonial Barman 41 Charles R. Thatcher (1831-1882) Dick Briggs from Australia 42 Taking the Census 45 Moggy's Wedding 46 Anonymous The Banks of the Condamine 48 The Stringybark Cockatoo 49 Henry Kendall (1839-1882) Bell-birds 50 Beyond Kerguelen 51 Anonymous John Gilbert was a Bushranger 53 Jack McGuire (?) The Streets of Forbes 55 E. -

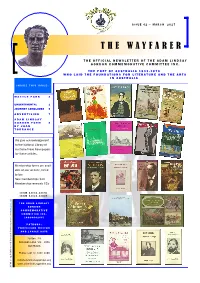

The Wayfarer

I S S U E 4 1 — MARCH 2017 THE WAYFARER THE OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE ADAM LIND S A Y GORDON COMMEMORATIVE COMMITTEE INC. THE POET OF AUSTRALIA 1833 - 1 8 7 0 WHO LAID THE FOUNDATIONS FOR LITERATURE AND THE ARTS IN AUSTRALIA INSIDE THIS ISSUE: WATTLE PARK 2 UNSENTIMENTAL 3 JOURNEY CONCLUDES 6 ADVERTISING 7 ADAM LINDSAY GORDON POEM 8 B Y J O A N TORRANCE We give acknowledgement to the National Library of Australia-Trove Newspapers for these articles. Membership forms are avail- able on our website, listed below. New memberships $20 Membership renewals $15 I S S N 1 8 3 4 - 4 0 7 0 I S S N 1 8 3 4 - 4 0 8 9 ) THE ADAM LINDSAY G O R D O N COMMEMORATIVE www.psrs.biz COMMITTEE INC. (A0049425F) P A T R O N S : PROFESSOR WESTON AND JANICE BATE PO Box 158 FLINDERS LANE VIC 8009 AUSTRALIA Phone: (+61 3) 5261 2899 [email protected] www.adamlindsaygordon.org A Publishing Solutions and Research Services production ( production Research Solutions and Services A Publishing THE WAYFARER Page 2 In an outback pub a bloke began to skite about his droving exploits. After a while he turned to a hard bittern old character. “And what’s the longest droving trip that you’ve been on?” He asked. The old character looked him squarely in the eye, “From Cape York to Hobart, son – and we walked them all the way”. (Treasury of Australian Folk Law- Walter Stone.) (Photo from Microsoft Media) Photo Wikmedia Commons ”Notes Tracker” WATTLE PARK WATTLE—MELBOURNE- Riversdale Rd, Burwood VIC 3125 The Argus, Melbourne. -

Newsletter of the Brisbane Water Historical Society

RED COW INN COORANBEAN HENRY KENDALL COTTAGE WEST GOSFORD CIRCA 1836 NEWSLETTER OF THE BRISBANE WATER HISTORICAL SOCIETY Vol. 43 Postal Address: 25- 27 Henry Kendall St., West Gosford, September No. 09 Phone: (02) 4325 2270 2020 Internet: www.henrykendallcottage.org.au email : [email protected] __________________________________________________________________________ BRISBANE WATER HISTORICAL SOCIETY INC. Founded 1950 Henry Kendall Cottage and Historical Museum Affiliated with Royal Australian Historical Society - Museums Galleries Australia (MGA) - Museum Galleries (MGNSW) – National Trust Disability Access : Free Parking __________________________________________________________________________ WHAT'S IN THIS NEWSLETTER • Welcome Everyone : Safety Plan p2 • Welfare : Snippets - New Refrigerator : Committee Meeting p3 • Some Past Events with BWHS - 5 years Ago : • 10 Years Ago & 20 Years Ago p4,p5 • Wattle Day : A Wattle Poem : p6,p7 • Food for Thought p7 • Patrons and Committee Members p8 Cooranbean Courier September 2020 2 WELCOME EVERYONE! The weather is getting a little warmer, it's lighter earlier, sunset's a little later, and birds are a little noisier - Spring is on the way! SAFETY PLAN With the Museum and Cottage re-opening this month, protecting the health of our visitors and volunteers is paramount and we have implemented a Safety Plan covering a range of hygiene and physical distancing measures in accordance with the NSW Government’s Public Health Order (No 3) 2020. A copy of the plan is available at Reception. Entry We are limiting the number of visitors to each section of the premises and you are asked to follow signage to maintain 4 square metres of space for each person. Signage will be displayed at each building entrance and internal area advising of the maximum capacity allowed. -

Excavating the Borders of Literary Anglo-Saxonism in Nineteenth-Century Britain and Australia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository LOUISE D’ARCENS AND CHRIS JONES Excavating the Borders of Literary Anglo-Saxonism in Nineteenth-Century Britain and Australia A NGLO-SAXONISM IS HARDLY A THING of the past. Nothing demonstrates this so potently as the media response to the 2009 discovery of a spectacular hoard of Anglo-Saxon objects by an amateur treasure hunter running his metal detector over a field in Staffordshire, England. This excitement is understandable: apart from the beauty of these objects, here is an irresistible story of how the Anglo-Saxon past is still with us—just there, under the topsoil, if we only look—and yet also vulnerable to loss, uncov- ered only by chance. This media response has been accompanied by a cho- rus of scholarly opinion proclaiming the hoard’s immeasurable historical value, deemed even greater than the Sutton Hoo ship burial, and relishing the unprecedented insight it promises into early medieval English life. This popular excitement has had its scholarly counterpart over the past decade in a surge in the study of medievalism—the postmedieval, imagina- tive reconstruction of the Middle Ages—by scholars originally trained in traditional medieval studies. These scholars have engaged in reflexive anal- ysis of the cultural assumptions underlying medievalist research, and in a rigorous anatomization of how the Middle Ages have signified for, and intersected with, later periods up to the present. The developing dialogue -

Women, the Media, and People from Other Countries Who Have Made Victoria – 1851 to Today

Women, the Media, and People from Other Countries who have made Victoria – 1851 to Today The Victoria Day Council 2008 La Trobe Lecture Queen’s Hall, Parliament of Victoria Saturday, July 5, 2008 at 7.00pm By Gary Morgan, Executive Chairman Roy Morgan Research ‘The real, central theme of History is not what happened, but what people felt about it when it was happening’. G M Young ‘When the thoughts of our forefathers, common thoughts about common things, will have become thinkable once more.’ Frederick Maitland Women in Positions of Power in Australia and Victoria • Julia Gillard, Deputy Prime Minister • Quentin Bryce, first woman Governor-General • Carmen Lawrence, first woman Premier of an Australian State (Western Australia) • Joan Kirner, first woman Premier of Victoria • Gail Kelly, CEO of Westpac (currently involved in Australia’s largest financial merger between Westpac and St. George Bank) • Marilyn Warren, Chief Justice (Victoria) • Pamela Tate, Solicitor General (Victoria) • Helen Silver, Secretary of Premier and Cabinet (the most senior Public Servant in Victoria) • Christine Nixon, Chief of Victoria Police • Prof. Sally Walker, Vice Chancellor of Deakin University • Prof. Margaret Gardner, Vice Chancellor of RMIT • Five women Victorian Ministers • Eight women Parliamentary Secretaries People from Other Countries in Positions of Power in Australia and Victoria • Prof. David de Kretser (Ceylon), Governor of Victoria • Sir James Gobbo (Italy), Governor of Victoria (1997-2000) • Sir Gustav Nossal (Austria), Nobel-winning scientist • John So (Hong Kong), Lord Mayor of Melbourne • Sir Arvi Parbo (Estonia), former Chairman of Western Mining and BHP • Prof. Hatem Salem (Egypt), Australian Centre for Blood Diseases • Prof. -

The Older Women's Network Nsw Annual Report 2019

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 THE OLDER WOMEN’S NETWORK NSW ANNUAL CONTENTS REPORT This report encapsulates Board Members 4 OWN NSW as it stands in 2019. Report from the Chair 5 In 2001, OWN NSW OWN NSW Staff 6 was incorporated as the peak body for OWN NSW Advocacy Work 6 affiliated groups in NSW, of which there Report from the Treasurer 7 are currently 17, including 7 Wellness Theatre Group 8 Centres. Aboriginal Support Circle 9 Newtown Wellness 10-11 Brisbane Water 12 Wyong 13 Blacktown Wellness 14 Bankstown Wellness 15 Illawarra Wellness & Illawarra 16-17 Northside Wellness 18 Penrith 18 Bankstown Greek 19 Macarthur 19 The Older Women’s Network Sydney 20 NSW gratefully acknowledges the Sutherland Wellness 21 support received from Family and Community Services Deep Water Woy Woy 22 of the New South Wales government, Nowra 22-23 the South Western Sydney Local Health Wollondilly 23 District and the City of Sydney. 2 CONTENTS Board Members 4 Report from the Chair 5 OWN NSW Staff 6 OWN NSW Advocacy Work 6 Report from the Treasurer 7 Theatre Group 8 “Women are traditional Aboriginal Support Circle 9 spinners - of tales, of cloth, Newtown Wellness 10-11 of many fine things. May we in OWN continue to spin Brisbane Water 12 strong webs of support Wyong 13 which create a safety net for Blacktown Wellness 14 older women’s emotional Bankstown Wellness 15 and physical wellbeing; and Illawarra Wellness & Illawarra 16-17 create a sling from which to catapult into the wider Northside Wellness 18 community older women’s Penrith 18 aspirations for a Bankstown Greek 19 better world.” Macarthur 19 Noreen Hewett Sydney 20 Sutherland Wellness 21 Deep Water Woy Woy 22 Nowra 22-23 Wollondilly 23 3 BOARD MEMBERS BEVERLEY BAKER Chair Beverly has served as the President of the Federation of Parents and Citizens Associations (NSW) advocating for parents with students in public schools. -

Richard Henry Horne (Richard Hengist Horne)

RICHARD HENRY HORNE (RICHARD HENGIST HORNE) RICHARD HENRY HORNE RICHARD HENGIST HORNE “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY HDT WHAT? INDEX RICHARD HENGIST HORNE RICHARD HENRY HORNE 1802 December 31, Friday: Richard Henry Horne was born in Edmonton, a northern suburb of London, as the eldest son of James Horne, a quartermaster in the 61st Regiment of Foot (South Gloucestershire). Intended for a military career like that of his father, he would be educated at a school in Edmonton, but then in a student rebellion at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich would be found to have, sin of sins, caricatured the headmaster. He was asked to leave, and entered the Sandhurst military college but would receive no commission. Upon graduation he would fail to obtain a position with the East India Company. By the Treaty of Bassein, the Peshwa of Poona ceded his independence and that of the Maratha Confederacy to the British East India Company. NOBODY COULD GUESS WHAT WOULD HAPPEN NEXT “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project Richard Hengist Horne HDT WHAT? INDEX RICHARD HENRY HORNE RICHARD HENGIST HORNE 1823 Reading QUEEN MAB; A PHILOSOPHICAL POEM: WITH NOTES. BY PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY, a celebration of the merits of republicanism, atheism, vegetarianism, and free love, Richard Henry Horne determined that he also was going to make of himself a poet. LIFE IS LIVED FORWARD BUT UNDERSTOOD BACKWARD? — NO, THAT’S GIVING TOO MUCH TO THE HISTORIAN’S STORIES. LIFE ISN’T TO BE UNDERSTOOD EITHER FORWARD OR BACKWARD. “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project Richard Hengist Horne HDT WHAT? INDEX RICHARD HENGIST HORNE RICHARD HENRY HORNE 1825 Mexico, while still subject to Spain in 1821, had granted land within the Mexican state of Texas to Moses Austin.