Factors Contributing to the Prevalence of Unplanned

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Informal Support for People with Alzheimer's Disease and Related D

Informal Support for People With Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias in Rural Uganda: A Qualitative Study Pia Ngoma Nankinga ( [email protected] ) Mbarara University of Science and Technology Samuel Maling Maling Mbarara University of Science and Technology Zeina Chemali Havard Medical School Edith K Wakida Mbarara University of Science and Technology Celestino Obua Mbarara University of Science and Technology Elialilia S Okello Makerere University Research Keywords: Informal support, dementia and rural communities Posted Date: December 17th, 2019 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.2.19063/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/16 Abstract Background: The generation of people getting older has become a public health concern worldwide. People aged 65 and above are the most at risk for Alzheimer’s disease which is associated with physical and behavioral changes. This nurtures informal support needs for people living with dementia where their families together with other community members are the core providers of day to day care for them in the rural setting. Despite global concern around this issue, information is still lacking on informal support delivered to these people with dementia. Objective: Our study aimed at establishing the nature of informal support provided for people with dementia (PWDs) and its perceived usefulness in rural communities in South Western Uganda. Methods: This was a qualitative study that adopted a descriptive design and conducted among 22 caregivers and 8 opinion leaders in rural communities of Kabale, Mbarara and Ibanda districts in South Western Uganda. The study included dementia caregivers who had been in that role for a period of at least six months and opinion leaders in the community. -

The Case of Bushenyi-Ishaka, Uganda

Water governance in small towns at the rural-urban intersection: the case of Bushenyi-Ishaka, Uganda Ramkrishna Paul MSc Thesis WM-WQM.18-14 March 2018 Sketch Credits: Ramkrishna Paul Water governance in small towns at the rural-urban intersection: the case of Bushenyi-Ishaka, Uganda Master of Science Thesis by Ramkrishna Paul Supervisor Dr. Margreet Zwarteveen Mentor Dr. Jeltsje Kemerink - Seyoum Examination committee Dr. Margreet Zwarteveen, Dr. Jeltsje Kemerink – Seyoum, Dr. Janwillem Liebrand This research is done for the partial fulfilment of requirements for the Master of Science degree at the UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education, Delft, the Netherlands Delft March 2018 Although the author and UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education have made every effort to ensure that the information in this thesis was correct at press time, the author and UNESCO- IHE do not assume and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by errors or omissions, whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident, or any other cause. © Ramkrishna Paul 2018. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Abstract Water as it flows through a town is continuously affected and changed by social relations of power and vice-versa. In the course of its flow, it always benefits some, while depriving, or even in some cases harming others. The issues concerning distribution of water are closely intertwined with the distribution of risks, at the crux of which are questions related to how decisions related to water allocation and distribution are made. -

Report Micro-Research Workshop Makerere University

Micro-Research Report Micro-Research Workshop Makerere University “Nurturing an Academic Career from Research Ideas to Finished Papers-using Micro-Research” Workshop for Community Based Researchers Held at Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda From August 2 to 13, 2010 Lecturers Robert Bortolussi, MD FRCPC, Professor Pediatrics, Noni MacDonald, MD, FRCPC, FCAHS, Professor of Pediatrics, IWK Health Centre and Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada and Eric Wobudeya, Department of Pediatrics and Paul Kutyabami, Department of Pharmacy, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda Ugandan Mentor Kasangaki Arabati, Faculty of Dentistry, Makerere University Funding Sponsors Micro-Research, IWK Health Centre And Canadian Child Health Clinician Scientist Program (CCHCSP) Report Makerere Workshop 2010 Page 1 Micro-Research Introduction and Background The absolute need for capacity building in research was recognized several years ago by African nations. Lack of grant funds for small research projects is a major obstacle to research development in developing countries. Small projects are the fuel, upon which research skills are honed and a track record is established, a critical factor in any research grant proposal. In March 2009, Drs. Noni MacDonald and Robert Bortolussi were awarded funds from CCHCSP for a pilot Micro-Research infrastructure project. Micro-Research, a concept modeled on Micro–Finance, was conceived by Jerome Kabakyenga, Dean of Medicine of Mbarara University of Science and Technology (MUST), Noni MacDonald and Bob Bortolussi in 2008 (Appendix 1). The CCHCSP pilot project would use educational tools, mentors, seed grant support and peer-to-peer interaction with CCHCSP and Ugandan researchers. The program of the workshop at Makerere University was modeled after an earlier workshop but modified to address issues such as grant reviewing, knowledge translation and community engagement. -

Mitooma District Community Knowledge and Practices LQAS Survey Report

Mitooma District Community Knowledge and Practices LQAS Survey Report Management Sciences for Health (STAR-E) April 2011 This report was made possible through support provided by the US Agency for International Development, under the terms of Cooperative Agreement Number 617‐A‐00‐09‐00006‐00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the US Agency for International Development. Strengthening TB and HIV & AIDS Responses in Eastern Uganda (STAR-E) Management Sciences for Health 784 Memorial Drive Cambridge, MA 02139 Telephone: (617) 250-9500 www.msh.org MITOOMA DISTRICT COMMUNITY KNOWLEDGE AND PRACTICES SURVEY REPORT APRIL 2011 MITOOMA MITOOMA DISTRICT COMMUNITY KNOWLEDGE AND PRACTICES SURVEY REPORT APRIL 2011 Prepared by STAR- E LQAS __________________________________________________________________________________ Mitooma Mitooma District Knowledge and Practices Survey Report, 2010 This document may be cited as: Author: Management Sciences in Health (STAR-E) and Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation (STAR-SW) Title: Community knowledge and practices LQAS survey, 2010. Mitooma district report, May 2011. Contacts: Stephen K. Lwanga ([email protected]) and Edward Bitarakwate ([email protected]) Mitooma District Knowledge and Practices Survey Report, 2010 Page i Acknowledgements STAR-E acknowledges with appreciation the cooperation it has received from the partners contributing to the 2010 LQAS survey in Mitooma district: the communities that participated, the district authorities for oversight and supervision, the district officials for carrying out the survey under the management and guidance of the STAR-SW and STAR-E projects. STAR-E thanks STAR-SW for providing the electronic survey raw data sets as soon as they were ready. -

Disability & Special Needs Policy

DISABILITY & SPECIAL NEEDS POLICY DISABILITY IS A MINDSET MBARARAMBARARA UNIVERSITYUNIVERSITY OFOF SCIENCESCIENCE && TECHNOLOGYTECHNOLOGY SUCCEED WE MUST 2019JUNE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I reserve special plaudits for the African Development Bank that funded the formulation of this policy. We also offer special thanks to Ms. Reste Ndholorwa who coordinated all cross cutting issues in the ADB HEST project, (TA/CCAHEST Project). Her commitment and guidance cannot be forgotten. During the formulation of the policy, benchmarking was done at Kyambogo University, Makerere University Business school, Nkumba University and Uganda Christian University –Mukono. I acknowledge the contribution of these Universities, and would like to extend sincere thanks to the following: • Dr. Eron Lawrence, the Dean, Faculty of Special Needs and Rehabilitation, Kyambogo University, for the time and effort made to guide us in the process. • Mr. Muteesa Mungereza Ayub, Dean of Students Department, Uganda Christian University- Mukono for the warm reception and the willingness to share information to facilitate our interactions. • Ms Juliet Kateega and Mr. Vincent Balabyeki, Dean of Students Department, Makerere University Business School for their invaluable support to our cause. • Ms Elisa Nsereko the University warden/counsellor, Nkumba University for her insights into the management of the PWDs. Special thanks also go to the facilitators of the consultative meetings, namely, Ms Twembi Topisita from Human Right Commission, Mr. Besiga John from NUDIPU, Ms Nakalema Gladys, and Dr, Ssenyonga Joseph from the Faculty of Science with Education (MUST), Fr. David Nuwagaba- sign language interpreter from Montfort Missionaries, and Ms. Atwongire Loice. Their tireless efforts have led to the development of this policy for which we are thankful. -

Strategic Profiles of the International Dimension in Universities in Uganda Ronald Bisaso and Florence Nakamanya

Strategic Profiles of the International Dimension in Universities in Uganda Ronald Bisaso and Florence Nakamanya Abstract This article is based on a study that explored the nature of and variations in strategic profiles of internationalisation in universities in Uganda. Six universities, comprising of three public and three private chartered uni- versities with different histories and philosophies were selected for the study. Profiles of the international dimension were ascertained through a review and analysis of national and institutional strategic plans and reports. The findings highlight six profiles of internationalisation, namely, vision and mission, shared/core value, student enrolment, staff and student exchange, partnerships and collaborations, and the management structure. It is imperative that universities integrate internationalisation as an ethos that is systematically mainstreamed in all activities, produce knowledge relevant to local and international audiences, and improve the manage- ment structure by deploying managerial capacity that corresponds to the strategic period. The article recommends that further research should be conducted on profiles of the international dimension. Key words: internationalisation, international dimension, strategic pro- files, university, Uganda Ce article se fonde sur une étude qui a exploré la nature de et les variations dans les profils stratégiques d’internationalisation dans les universités en Ouganda. Six universités, composées de trois publiques et trois privées agréées, avec des histoires et des philosophies différentes, ont été sélec- tionnées pour l’étude. Les profils de rayonnement international ont été vérifiées avec un examen et une analyse des plans stratégiques et des rap- about the authors: ronald bisaso and florence nakamanya East African School of Higher Education Studies and Development, Makerere University. -

The Perception of Ishaka – Bushenyi Municipality Residents on Male Circumcision Towards Reduction of Hiv/Aids

THE PERCEPTION OF ISHAKA – BUSHENYI MUNICIPALITY RESIDENTS ON MALE CIRCUMCISION TOWARDS REDUCTION OF HIV/AIDS. BY PETER OLYAM (BMS/0151/62/DF) RESEARCH PROJECT PROPOSAL SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF MEDICINE AND BACHELOR OF SURGERY AT KAMPALA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY JULY, 2013 KAMPALA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY- WESTERN CAMPUS FACULTY OF CLINICAL MEDICINE AND DENTISTRY P.O BOX 71 BUSHENYI UGANDA Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................................................. v TABLE OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................................... vi DECLARATION ............................................................................................................................................. vii DEDICATION ............................................................................................................................................... viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT .................................................................................................................................. ix LIST OF ABREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ..................................................................................................... x ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................................... -

Uganda Developing Subnational Estimates of Hiv Prevalence and the Number of People

UNAIDS 2014 | REFERENCE UGANDA DEVELOPING SUBNATIONAL ESTIMATES OF HIV PREVALENCE AND THE NUMBER OF PEOPLE LIVING WITH HIV UNAIDS / JC2665E (English original, September 2014) Copyright © 2014. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). All rights reserved. Publications produced by UNAIDS can be obtained from the UNAIDS Information Production Unit. Reproduction of graphs, charts, maps and partial text is granted for educational, not-for-profit and commercial purposes as long as proper credit is granted to UNAIDS: UNAIDS + year. For photos, credit must appear as: UNAIDS/name of photographer + year. Reproduction permission or translation-related requests—whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution—should be addressed to the Information Production Unit by e-mail at: [email protected]. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNAIDS concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. UNAIDS does not warrant that the information published in this publication is complete and correct and shall not be liable for any damages incurred as a result of its use. METHODOLOGY NOTE Developing subnational estimates of HIV prevalence and the number of people living with HIV from survey data Introduction prevR Significant geographic variation in HIV Applying the prevR method to generate maps incidence and prevalence, as well as of estimates of the number of people living programme implementation, has been with HIV (aged 15–49 and 15 and older) and observed between and within countries. -

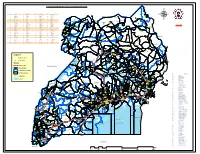

Legend " Wanseko " 159 !

CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA_ELECTORAL AREAS 2016 CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA GAZETTED ELECTORAL AREAS FOR 2016 GENERAL ELECTIONS CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY 266 LAMWO CTY 51 TOROMA CTY 101 BULAMOGI CTY 154 ERUTR CTY NORTH 165 KOBOKO MC 52 KABERAMAIDO CTY 102 KIGULU CTY SOUTH 155 DOKOLO SOUTH CTY Pirre 1 BUSIRO CTY EST 53 SERERE CTY 103 KIGULU CTY NORTH 156 DOKOLO NORTH CTY !. Agoro 2 BUSIRO CTY NORTH 54 KASILO CTY 104 IGANGA MC 157 MOROTO CTY !. 58 3 BUSIRO CTY SOUTH 55 KACHUMBALU CTY 105 BUGWERI CTY 158 AJURI CTY SOUTH SUDAN Morungole 4 KYADDONDO CTY EST 56 BUKEDEA CTY 106 BUNYA CTY EST 159 KOLE SOUTH CTY Metuli Lotuturu !. !. Kimion 5 KYADDONDO CTY NORTH 57 DODOTH WEST CTY 107 BUNYA CTY SOUTH 160 KOLE NORTH CTY !. "57 !. 6 KIIRA MC 58 DODOTH EST CTY 108 BUNYA CTY WEST 161 OYAM CTY SOUTH Apok !. 7 EBB MC 59 TEPETH CTY 109 BUNGOKHO CTY SOUTH 162 OYAM CTY NORTH 8 MUKONO CTY SOUTH 60 MOROTO MC 110 BUNGOKHO CTY NORTH 163 KOBOKO MC 173 " 9 MUKONO CTY NORTH 61 MATHENUKO CTY 111 MBALE MC 164 VURA CTY 180 Madi Opei Loitanit Midigo Kaabong 10 NAKIFUMA CTY 62 PIAN CTY 112 KABALE MC 165 UPPER MADI CTY NIMULE Lokung Paloga !. !. µ !. "!. 11 BUIKWE CTY WEST 63 CHEKWIL CTY 113 MITYANA CTY SOUTH 166 TEREGO EST CTY Dufile "!. !. LAMWO !. KAABONG 177 YUMBE Nimule " Akilok 12 BUIKWE CTY SOUTH 64 BAMBA CTY 114 MITYANA CTY NORTH 168 ARUA MC Rumogi MOYO !. !. Oraba Ludara !. " Karenga 13 BUIKWE CTY NORTH 65 BUGHENDERA CTY 115 BUSUJJU 169 LOWER MADI CTY !. -

Undergraduate Private Admissions 2020/2021 Academic Year

MBARARA UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY OFFICE OF THE ACADEMIC REGISTRAR P.O. Box 1410, MBARARA-UGANDA Telephone: +256-485-660584, +256-414-668971 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Web: www.must.ac.ug UNDERGRADUATE PRIVATE ADMISSIONS 2020/2021 ACADEMIC YEAR The following have been admitted to the different programmes as below for the 2020/2021 academic year. Admission letters shall be sent by email to applicants who have paid a NON-REFUNDABLE TUITION FEES DEPOSIT of Shs. 50,000=. Visit www.must.ac.ug for instructions on how to pay or contact us by email [email protected] or WhatsApp us on +256-786-706490. BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN COMPUTER ENGINEERING SN NAME GENDER NATIONALITY DISTRICT ALEVEL_INDEX YEAR WEIGHT 1 BATAMYE ABDUL M Ugandan BUIKWE U1609/635 2019 47.1 2 BONGO JOSHUA M Ugandan APAC U2060/581 2019 44.2 3 KIA JANET F Ugandan ALEBTONG U1923/610 2019 43.7 4 NSHEKANABO MARIUS M Ugandan SHEEMA U1063/563 2019 41.3 5 BINTO NAOMI F Ugandan MUKONO U2583/568 2019 40.7 6 BWAMBALE ROBERT SEMAKULA M Ugandan KASESE U3231/514 2019 31.5 7 MUTEBI JONATHAN M Ugandan WAKISO U0053/823 2019 31.2 8 ARINAITWE JULIUS M Ugandan MBARARA U1495/554 2017 31.1 9 ATWIINE SAGIUS M Ugandan NTUNGAMO U0946/572 2019 28.0 10 KISAKYE JULIUS M Ugandan IGANGA U0027/564 2019 27.6 11 MUKWATANISE ALBERT M Ugandan ISINGIRO U0334/692 2019 27.6 12 MATEGE DERICK M Ugandan KAMULI U2877/614 2012 27.1 13 MUHUMUZA JOSEPH M Ugandan KISORO U0080/566 2019 25.2 14 MWEBESA TREVOR M Ugandan NTUNGAMO U0053/827 2019 25.2 15 KAANYI JANE PATIENCE F Ugandan KIBUKU U0065/586 -

Kampala, Uganda; Telephone: (256-414) 7060000 Fax: (256-414) 237553/230370; E-Mail: [email protected]; Website

2014 NPHC - Main Report National Population and Housing Census 2014 Main Report 2014 NPHC - Main Report This report presents findings from the National Population and Housing Census 2014 undertaken by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). Additional information about the Census may be obtained from the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS), Plot 9 Colville Street, P.O. box 7186 Kampala, Uganda; Telephone: (256-414) 7060000 Fax: (256-414) 237553/230370; E-mail: [email protected]; Website: www.ubos.org. Cover Photos: Uganda Bureau of Statistics Recommended Citation Uganda Bureau of Statistics 2016, The National Population and Housing Census 2014 – Main Report, Kampala, Uganda 2014 NPHC - Main Report FOREWORD Demographic and socio-economic data are The Bureau would also like to thank the useful for planning and evidence-based Media for creating awareness about the decision making in any country. Such data Census 2014 and most importantly the are collected through Population Censuses, individuals who were respondents to the Demographic and Socio-economic Surveys, Census questions. Civil Registration Systems and other The census provides several statistics Administrative sources. In Uganda, however, among them a total population count which the Population and Housing Census remains is a denominator and key indicator used for the main source of demographic data. resource allocation, measurement of the extent of service delivery, decision making Uganda has undertaken five population and budgeting among others. These Final Censuses in the post-independence period. Results contain information about the basic The most recent, the National Population characteristics of the population and the and Housing Census 2014 was undertaken dwellings they live in. -

Prevalence and Correlates of Alzheimer's Disease and Related

Mubangizi et al. BMC Geriatrics (2020) 20:48 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-1461-z RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Prevalence and correlates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in rural Uganda: cross-sectional, population-based study Vincent Mubangizi1* , Samuel Maling1, Celestino Obua1 and Alexander C. Tsai1,2 Abstract Background: There is a paucity of data on the prevalence and correlates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in sub-Saharan Africa. The aim of the study was to estimate the prevalence and correlates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in rural Uganda. Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional, population-based study in a rural region of southwestern Uganda. The Brief Community Screening Instrument for Dementia was administered to a multi-stage area probability sample of 400 people aged 60 years and over. Multivariable logistic regression was used to estimate correlates of probable dementia. Results: Overall, 80 (20%) of the sample screened positive for dementia. On multivariable regression, we estimated the following correlates of probable dementia: age (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.02 per year; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.10–1.03, p<0.001), having some formal education (AOR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.41–0.81, p = 0.001), exercise (AOR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.27–0.72, p = 0.001), and having a ventilated kitchen (AOR, 0.43; (95% CI, 0.24–0.77, p =0.001). Conclusions: In this population-based sample of older-age adults in rural Uganda, nearly one-fifth screened positive for dementia. Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Dementia, Sub-Saharan Africa, Uganda Background psychological factors, infectious diseases, genetic factors, Alzheimer’s disease, other dementias, and non- and carbon monoxide poisoning.