Bryanston Films : an Experiment in Cooperative Independent Production and Distribution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maggie-Dp.Pdf

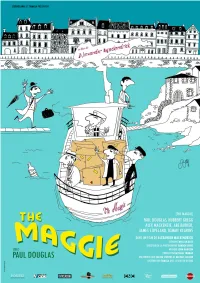

STUDIOCANAL et TAMASA présentent un film de Alexander Mackendrick ç Version restaurée UK - Durée 1h32 ç Sortie le 16 décembre 2015 ç Presse Frédérique Giezendanner [email protected] T. 06 10 37 16 00 Distribution TAMASA [email protected] T. 01 43 59 01 01 Visuels téléchargeables sur www.tamasadiffusion.com SYNOPSIS Le Capitaine de la « Maggie », Mac Taggart, ne possède pas suffisamment d’argent pour faire réparer son bateau qui tient la mer par miracle, malgré les réticences des autorités portuaires. Par suite d’un malentendu, Pusey, représentant un riche Américain, Marshall, lui confie le transport d’un matériel couteux destiné à la modernisation d’un château. Découvrant la supercherie, Marshall, atterré, essaye de récupérer son précieux chargement. Mais après bien des incidents, bien des événements inattendus avec ce curieux équipage, le chargement finira au fond de la mer. Mais Mac Taggart conserve l’argent que lui a remis Marshall pour faire réparer son vieux bateau. ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK Alexander Mackendrick est né à Boston, dans l’État du Massachusetts. À 6 ans, son père meurt emporté par la grippe « espagnole ». Sa mère, qui devait trouver du travail pour survivre, décide de devenir couturière. Elle céda la garde de son fils au grand-père qui vivait en Écosse. C’est ainsi qu’à l’âge de sept ans, Mackendrick revient sur la terre de ses aïeux. Il vit une enfance très solitaire et difficile. Après des études d’art, il part s’installer à Londres dans les années 30 pour travailler comme directeur artistique. Entre 1936 et 1938, Mackendrick est l’auteur du script de publicités cinématographiques. -

Darrol Blake Transcript

Interview with Darrol Blake by Dave Welsh on Tuesday the 21st of September 2010 Dave Welsh: Okay, this is an interview with Darrol Blake on Tuesday the 21st of September 2010, for the Britain at Work Project, West London, West Middlesex. Darrol, I wonder if you'd mind starting by saying how you got into this whole business. Darrol Blake: Well, I'd always wanted to be the man who made the shows, be it for theatre or film or whatever, and this I decided about the age of eleven or twelve I suppose, and at that time I happened to win a scholarship to grammar school, in West London, in Hanwell, and formed my own company within the school, I was in school plays and all that sort of thing, so my life revolved around putting on shows. Nobody in my family had ever been to university, so I assumed that when I got to sixteen I was going out to work. I didn't even assume I would go into the sixth form or anything. So when I did get to sixteen I wrote around to all the various places that I thought might employ me. Ealing Studios were going strong at that time, Harrow Coliseum had a rep. The theatre at home in Hayes closed on me. I applied for a job at Windsor Rep, and quite by the way applied to the BBC, and the only people who replied were the BBC, and they said we have vacancies for postroom boys, office messengers, and Radio Times clerks. -

MAESTROS DEL CINE CLÁSICO (X): ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK (En El 105 Aniversario De Su Nacimiento)

Cineclub Universitario / Aula de Cine P r o g r a m a c i ó n d e febrero 2 0 1 7 MAESTROS DEL CINE CLÁSICO (X): ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK (en el 105 aniversario de su nacimiento) Fotografía: Proyector “Marín” de 35mm (ca.1970). Cineclub Universitario Foto:Jacar [indiscreetlens.blogspot.com] (2015). El CINECLUB UNIVERSITARIO se crea en 1949 con el nombre de “Cineclub de Granada”. Será en 1953 cuando pase a llamarse con su actual denominación. Así pues en este curso 2016-2017, cumplimos 63 (67) años. FEBRERO 2017 MAESTROS DEL CINE CLÁSICO (X): ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK (en el 105 aniversario de su nacimiento) FEBRUARY 2017 MASTERS OF CLASSIC CINEMA (X): ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK (105 years since his birth) Viernes 3 / Friday 3th • 21 h. WHISKY A GOGÓ (1949) (WHISKY GALORE!) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Martes 7 / Tuesday 7th • 21 h. EL HOMBRE VESTIDO DE BLANCO (1951) (THE MAN IN THE WHITE SUIT) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Viernes 10 / Friday 10th • 21 h. MANDY (1952) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Martes 14 / Tuesday 14th • 21 h. EL QUINTETO DE LA MUERTE (1955) (THE LADYKILLERS) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Viernes 17 / Friday 17th • 21 h. CHANTAJE EN BROADWAY / EL DULCE SABOR DEL ÉXITO (1957) (SWEET SMELL OF SUCCESS) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Martes 21 / Tuesday 21th • 21 h. SAMMY, HUIDA HACIA EL SUR (1963) (SAMMY GOING SOUTH) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Todas las proyecciones en la Sala Máxima de la ANTIGUA FACULTAD DE MEDICINA (Av. -

The Queer" Third Species": Tragicomedy in Contemporary

The Queer “Third Species”: Tragicomedy in Contemporary LGBTQ American Literature and Television A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department English and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences by Lindsey Kurz, B.A., M.A. March 2018 Committee Chair: Dr. Beth Ash Committee Members: Dr. Lisa Hogeland, Dr. Deborah Meem Abstract This dissertation focuses on the recent popularity of the tragicomedy as a genre for representing queer lives in late-twentieth and twenty-first century America. I argue that the tragicomedy allows for a nuanced portrayal of queer identity because it recognizes the systemic and personal “tragedies” faced by LGBTQ people (discrimination, inadequate legal protection, familial exile, the AIDS epidemic, et cetera), but also acknowledges that even in struggle, in real life and in art, there is humor and comedy. I contend that the contemporary tragicomedy works to depart from the dominant late-nineteenth and twentieth-century trope of queer people as either tragic figures (sick, suicidal, self-loathing) or comedic relief characters by showing complex characters that experience both tragedy and comedy and are themselves both serious and humorous. Building off Verna A. Foster’s 2004 book The Name and Nature of Tragicomedy, I argue that contemporary examples of the tragicomedy share generic characteristics with tragicomedies from previous eras (most notably the Renaissance and modern period), but have also evolved in important ways to work for queer authors. The contemporary tragicomedy, as used by queer authors, mixes comedy and tragedy throughout the text but ultimately ends in “comedy” (meaning the characters survive the tragedies in the text and are optimistic for the future). -

Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 12-2016 Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Elrick, Kathy, "Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News" (2016). All Dissertations. 1847. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1847 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IRONIC FEMINISM: RHETORICAL CRITIQUE IN SATIRICAL NEWS A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Rhetorics, Communication, and Information Design by Kathy Elrick December 2016 Accepted by Dr. David Blakesley, Committee Chair Dr. Jeff Love Dr. Brandon Turner Dr. Victor J. Vitanza ABSTRACT Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News aims to offer another perspective and style toward feminist theories of public discourse through satire. This study develops a model of ironist feminism to approach limitations of hegemonic language for women and minorities in U.S. public discourse. The model is built upon irony as a mode of perspective, and as a function in language, to ferret out and address political norms in dominant language. In comedy and satire, irony subverts dominant language for a laugh; concepts of irony and its relation to comedy situate the study’s focus on rhetorical contributions in joke telling. How are jokes crafted? Who crafts them? What is the motivation behind crafting them? To expand upon these questions, the study analyzes examples of a select group of popular U.S. -

The Finance and Production of Independent Film and Television in the UK: a Critical Introduction

The Finance and Production of Independent Film and Television in the UK: A Critical Introduction Vital Statistics General Population: 64.1m Size: 241.9 km sq GDP: £1.9tr (€2.1tr) Film1 Market share of UK independent films in 2015: 10.5% Number of feature films produced: 201 Average visits to cinema per person per year: 2.7 Production spend per year: £1.4m (€1.6) TV2 Audience share of the main publicly-funded PSB (BBC): 72% Production spend by PSBs: £2.5bn (€3.2bn) Production spend by commercial channels (excluding sport): £350m (€387m) Time spent watching television per day: 193 minutes (3hrs 13 minutes) Introduction This chapter provides an overview of independent film and television production in the UK. Despite the unprecedented levels of convergence that characterise the digital era, the UK film and television industries remain distinct for several reasons. The film industry is small and fragmented, divided across the two opposing sources of support on which it depends: large but uncontrollable levels of ‘inward-investment’ – money invested in the UK from overseas – mainly from the US, and low levels of public subsidy. By comparison, the television industry is large and diverse, its relative stability underpinned by a long-standing infrastructure of 1 Sources: BFI 2016: 10; ‘The Box Office 2015’ [market share of UK indie films] ; BFI 2016: 6; ‘Exhibition’ [cinema visits per per person]; BFI 2016: 6; ‘Exhibition’ [average visits per person]; BFI 2016: 3; ‘Screen Sector Production’ [production spend per year]. 2 Sources: Oliver & Ohlbaum 2016: 68 [PSB audience share]; Ofcom 2015a: 3 [PSB production spend]; Ofcom 2015a: 8. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Billam, Alistair It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Original Citation Billam, Alistair (2018) It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34583/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Submission in fulfilment of Masters by Research University of Huddersfield 2016 It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Alistair Billam Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Ealing and post-war British cinema. ................................................................................... 12 Chapter 2: The community and social realism in It Always Rains on Sunday ...................................... 25 Chapter 3: Robert Hamer and It Always Rains on Sunday – the wider context. -

And Neva Satterlee Mcnally Vaudeville Collection

Guide to the George E. "Mello" and Neva Satterlee McNally Vaudeville Collection NMAH.AC.0760 Franklin A. Robinson, Jr. 2002 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Original Sheet Music................................................................................ 4 Series 2: Commercial Sheet Music.......................................................................... 5 Series 3: Photographs.............................................................................................. 7 Series 4: Memorabilia.............................................................................................. -

EARL CAMERON Sapphire

EARL CAMERON Sapphire Reuniting Cameron with director Basil Dearden after Pool of London, and hastened into production following the Notting Hill riots of summer 1958, Sapphire continued Dearden and producer Michael Relph’s valuable run of ‘social problem’ pictures, this time using a murder-mystery plot as a vehicle to sharply probe contemporary attitudes to race. Cameron’s role here is relatively small, but, playing the brother of the biracial murder victim of the title, the actor makes his mark in a couple of memorable scenes. Like Dearden’s later Victim (1961), Sapphire was scripted by the undervalued Janet Green. Alex Ramon, bfi.org.uk Sapphire is a graphic portrayal of ethnic tensions in 1950s London, much more widespread and malign than was represented in Dearden’s Pool of London (1951), eight years earlier. The film presents a multifaceted and frequently surprising portrait that involves not just ‘the usual suspects’, but is able to reveal underlying insecurities and fears of ordinary people. Sapphire is also notable for showing a successful, middle-class black community – unusual even in today’s British films. Dearden deftly manipulates tension with the drip-drip of revelations about the murdered girl’s life. Sapphire is at first assumed to be white, so the appearance of her black brother Dr Robbins (Earl Cameron) is genuinely astonishing, provoking involuntary reactions from those he meets, and ultimately exposing the real killer. Small incidents of civility and kindness, such as that by a small child on a scooter to Dr Robbins, add light to a very dark film. Earl Cameron reprises a role for which he was famous, of the decent and dignified black man, well aware of the burden of his colour. -

Shepperton Studios Has Submitted Plans Fo

PRESS RELEASE SHEPPERTON STUDIOS SUBMITS PLANS FOR EXPANSION London, 21st August 2018: Shepperton Studios has submitted plans for the redevelopment and expansion of the world-renowned site in Surrey, England, which will deliver a world class studio with a certain future. A planning application has been lodged with Spelthorne Borough Council seeking consent for the £500 million private sector development project which will deliver an increase in stage space of around 465,000 sq ft and associated support facilities. The development will bring the studio up to the scale and standard of its sister Pinewood Studios and make it a truly world-class facility. The scheme is of national importance and follows on from the Government’s ambition to double the scale of film and high-end television production revenue to £4bn by 2025. Shepperton and Pinewood Studios will be vital facilities if the UK is to achieve this target. The expansion will secure the future of more than 1,500 direct jobs currently based in Spelthorne and maintain the current contribution to the local economy of £181 million Gross Value Added (GVA). Over the construction period 837 jobs per year will be created, including potential for more than 200 jobs in the borough. On completion, Shepperton Studios is expected to boost productivity within the local economy to a total of £322 million (GVA) and will create and sustain a total of 2,796 jobs. Andrew M. Smith, Director, Shepperton Studios said: “The UK is currently missing out on a significant number of international films because of a shortage of sound stages. -

(2020). Pinewood Studios, the Independent Frame, and Innovation

Street, S. (2020). Pinewood Studios, the Independent Frame, and Innovation. In B. R. Jacobson (Ed.), In the Studio: Visual Creation and Its Material Environments (1 ed., pp. 103-121). University of California Press. Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available via University of California Press at https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520297609/in-the-studio . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Pinewood Studios, the Independent Frame, and Innovation Sarah Street, University of Bristol British director Darrel Catling reported to the British trade press in February 1948 on the Independent Frame (IF), a new system of film production that had been launched at Pinewood Studios. Catling had recently used it to make Under the Frozen Falls, a short children’s film that had benefited from the IF’s aim to “rationalize that which is largely irrational in film making.”1 He described how his film had been very carefully pre-planned in terms of script, storyboards, and technical plans. Several scenes were pre-staged and filmed without the main cast who were later incorporated into scenes by means of rear projection. Special effects were of paramount importance in reducing the number of sets that needed to be built. -

Set in Scotland a Film Fan's Odyssey

Set in Scotland A Film Fan’s Odyssey visitscotland.com Cover Image: Daniel Craig as James Bond 007 in Skyfall, filmed in Glen Coe. Picture: United Archives/TopFoto This page: Eilean Donan Castle Contents 01 * >> Foreword 02-03 A Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire 04-07 B Argyll & The Isles 08-11 C Ayrshire & Arran 12-15 D Dumfries & Galloway 16-19 E Dundee & Angus 20-23 F Edinburgh & The Lothians 24-27 G Glasgow & The Clyde Valley 28-31 H The Highlands & Skye 32-35 I The Kingdom of Fife 36-39 J Orkney 40-43 K The Outer Hebrides 44-47 L Perthshire 48-51 M Scottish Borders 52-55 N Shetland 56-59 O Stirling, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs & Forth Valley 60-63 Hooray for Bollywood 64-65 Licensed to Thrill 66-67 Locations Guide 68-69 Set in Scotland Christopher Lambert in Highlander. Picture: Studiocanal 03 Foreword 03 >> In a 2015 online poll by USA Today, Scotland was voted the world’s Best Cinematic Destination. And it’s easy to see why. Films from all around the world have been shot in Scotland. Its rich array of film locations include ancient mountain ranges, mysterious stone circles, lush green glens, deep lochs, castles, stately homes, and vibrant cities complete with festivals, bustling streets and colourful night life. Little wonder the country has attracted filmmakers and cinemagoers since the movies began. This guide provides an introduction to just some of the many Scottish locations seen on the silver screen. The Inaccessible Pinnacle. Numerous Holy Grail to Stardust, The Dark Knight Scottish stars have twinkled in Hollywood’s Rises, Prometheus, Cloud Atlas, World firmament, from Sean Connery to War Z and Brave, various hidden gems Tilda Swinton and Ewan McGregor.