Political Methodology Committee on Concepts and Methods Working Paper Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January - April 2020 Program Brochure

JANUARY - APRIL 2020 PROGRAM BROCHURE EXPLORE THE OCEAN ABOARD A MOBILE VIRTUAL Town Hall SUBMARINE (GRADES 4-8) & (GRADES 9-12) 10 Central Street DETAILS INSIDE BROCHURE! Manchester MA 01944 Office Number: 978.526.2019 Fax Number: 978.526.2007 www.mbtsrec.com Director: Cheryl Marshall Program Director: Heather DePriest FEEDBACK How are we doing? If you have any comments, concerns or suggestions that might be helpful to us, please let us know! Call us at 978-526-2019 or email the Parks & Recreation Director, Cheryl Marshall at [email protected] MISSION: Manchester Parks & Recreation strives to offer programs and services that help to enhance quality of life through parks and exceptional recreation experiences. We provide opportunities for all residents to live, grow and develop into healthy, contributing members of our community. Whatever your age, ability or interest we have something for you! REGISTRATION INFORMATION HOWHOW TOTO REGISTERREGISTER FORFOR OUROUR PROGRAMS:PROGRAMS: Online: www.mbts.com You will need a username and password in order to utilize the online program registration system. Online registration is live. Walk in: Manchester by-the-Sea Recreation Town Hall 10 Central St Manchester. Payments can be made by check, credit card or cash. All payments are due at time of registration. Mail in: Manchester by-the-Sea Recreation Town Hall 10 Central St Manchester, MA 01944. A completed program waiver must be sent in along with full payment. Please do not send cash. Checks should be made out to Town of Manchester. If paying with a check, please indicate the program registering for in the memo & amounts. -

A Battle Royale

A Battle Royale In a previous article I looked at a game between 23... d7 two legendary Hoosier players and the theme XABCDEFGHY centered upon a far advanced pawn. Should 8-+r+-+k+( one attack, or try to queen the pawn? 7zpp+rwQpzpp' Here we will revisit this theme as it often comes 6-+-zP-+-+& into play. The question revolves about how 5+-+-sn-+-% much can you sacrifice in order to get that pawn to the promised land. 4-+-+Nwq-+$ 3+-+-+-+P# Before we get to the game, let me give you an exercise: [See the diagram at right.] 2PzP-+-zP-+" 1+K+RtR-+-! Your queen has just been attacked. Give yourself 15 minutes and decide upon what best xabcdefghy play might be, and how would you play? [What pair of Hoosiers have played the most games against each other? I would venture to say that two legendary players from Kokomo; John Roush and Phil Meyers would be my guess. I'd say they have probably crossed swords over the board more than a thousand times! (Especially when you include their marathon blitz sessions!) I witnessed their most recent battle royale at the recent Super Tornado organized by Nate Bush in Indianapolis at the Delta Hotel. But I'm also sure that by the time you are reading this that they will already have played many more games at the Kokomo IHOP in their ongoing journey across the chessboard. This encounter was played at a very fast time control [g45+5], but that might have seemed slow to these battle tested veterans. -

The Complete Hedgehog Foreword

Chess Sergey Shipov GemsThe Complete 1,000 Combinations You Should Know Hedgehog Volume I By Igor Sukhin Foreword by World Champion Vladimir Kramnik Boston © 2009 Sergey Shipov All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the Publisher. Publisher: Mongoose Press 1005 Boylston Street, Suite 324 Newton Highlands, MA 02461 [email protected] www.MongoosePress.com ISBN: 978-0-9791482-1-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2009932697 Distributed to the trade by National Book Network [email protected], 800-462-6420 For all other sales inquiries please contact the publisher. Translated by: James Marfia Layout: Semko Semkov Editorial Consultant: Jorge Amador Cover Design: Creative Center – Bulgaria First English edition 0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in China Contents Foreword 4 Introduction 5 The Hedgehog. Its Birth and Development 9 Getting to the Hedgehog Opening Structure 12 The Hedgehog Philosophy 20 Space and Order 25 Evaluating a Position 27 The English Hedgehog Preface 34 Part 1 Classical Continuation 7. d4 42 Chapter 1-1 History and Pioneers 43 Chapter 1-2 The English Hedgehog Tabiya – 7. d4 cxd4 8. Qxd4 69 Chapter 1-3 White Aims for a Quick Attack on the Pawn at d6 92 Chapter 1-4 Two Plans by Uhlmann 150 Chapter 1-5 Trading Off the Bishop at f6 214 Chapter 1-6 Notes on Move Orders in the 8. d4 System 278 Part 2 The 7. -

Fall 2008 Missouri Chess Bulletin

Missouri Chess Bulletin Missouri Chess Association www.mochess.org GM Benjamin Finegold GM Yasser Seirawan Volume 39 Number two —Summer/Fall 2012 Issue K Serving Missouri Chess Since 1973 Q TABLE OF CONTENTS ~Volume 39 Number 2 - Summer/Fall 2012~ Recent News in Missouri Chess ................................................................... Pg 3 From the Editor .................................................................................................. Pg 4 Tournament Winners ....................................................................................... Pg 5 There Goes Another Forty Years ................................................................... Pg 6-7 ~ John Skelton STLCCSC GM-in-Residence (Cover Story) ............................................... Pg 8 ~ Mike Wilmering World Chess Hall of Fame Exhibits ............................................................ Pg 9 Chess Clubs around the State ........................................................................ Pg 9 2012 Missouri Chess Festival ......................................................................... Pg 10-11 ~ Thomas Rehmeier Dog Days Open ................................................................................................. Pg 12-13 ~ Tim Nesham Top Missouri Chess Players ............................................................................ Pg 14 Chess Puzzles ..................................................................................................... Pg 15 Recent Games from Missouri Players ........................................................ -

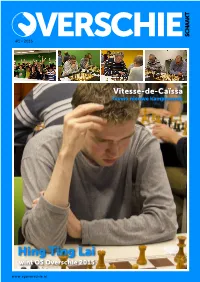

Overschie Schaakt Februari 2016

#1 • 2016 Laat uw verzekeringen doorlichten en krijg een onafhankelijk en vrijblijvend advies [email protected] Prins Mauritssingel 76c - 3043 PJ Rotterdam T 010 - 262 25 59 - M 06 -2757 0696 Overschie Schaakt februari 2016 Inhoud Verenigingsinformatie ________________________ 2 Algemeen ___________________________________ 2 3 Bestuur _____________________________________ 2 Wist u dat …? Trainers ____________________________________ 2 Deze keer in ‘Wist u dat …?’ Clubblad ____________________________________ 2 Website ____________________________________ 2 één van de beste schakers Contributie __________________________________ 2 aller tijden: Anatoli Karpov. Opzegging van het Lidmaatschap ________________ 2 Kortjes _____________________________________ 3 Agenda _____________________________________ 3 Schaken en Auteursrecht _______________________ 3 Actiefoto ____________________________________ 3 Wist u dat Anatoli Karpov …? ___________________ 3 Rectificatie __________________________________ 3 Overschie 1 _________________________________ 4 9 Bespiegelingen _______________________________ 4 Ronde 3, Souburg (uit) _________________________ 4 Overschie 2 Statistieken na Ronde 3 ________________________ 6 De strijd in RSB klasse 1A is Ronde 4, Charlois Europoort (thuis) _______________ 6 nog in volle gang. Ook voor Statistieken na Ronde 4 ________________________ 7 ons tweede team is het nog Ronde 5, CSV (uit) ____________________________ 8 spannend. De degradatielijn Statistieken na Ronde 5 ________________________ 9 -

A Proposed Heuristic for a Computer Chess Program

A Proposed Heuristic for a Computer Chess Program copyright (c) 2013 John L. Jerz [email protected] Fairfax, Virginia Independent Scholar MS Systems Engineering, Virginia Tech, 2000 MS Electrical Engineering, Virginia Tech, 1995 BS Electrical Engineering, Virginia Tech, 1988 December 31, 2013 Abstract How might we manage the attention of a computer chess program in order to play a stronger positional game of chess? A new heuristic is proposed, based in part on the Weick organizing model. We evaluate the 'health' of a game position from a Systems perspective, using a dynamic model of the interaction of the pieces. The identification and management of stressors and the construction of resilient positions allow effective postponements for less-promising game continuations due to the perceived presence of adaptive capacity and sustainable development. We calculate and maintain a database of potential mobility for each chess piece 3 moves into the future, for each position we evaluate. We determine the likely restrictions placed on the future mobility of the pieces based on the attack paths of the lower-valued enemy pieces. Knowledge is derived from Foucault's and Znosko-Borovsky's conceptions of dynamic power relations. We develop coherent strategic scenarios based on guidance obtained from the vital Vickers/Bossel/Max- Neef diagnostic indicators. Archer's pragmatic 'internal conversation' provides the mechanism for our artificially intelligent thought process. Initial but incomplete results are presented. keywords: complexity, chess, game -

Download the Latest Catalogue

TABLE OF CONTENTS To view a particular category within the catalogue please click on the headings below 1. Antiquarian 2. Reference; Encyclopaedias, & History 3. Tournaments 4. Game collections of specific players 5. Game Collections – General 6. Endings 7. Problems, Studies & “Puzzles” 8. Instructional 9. Magazines & Yearbooks 10. Chess-based literature 11. Children & Junior Beginners 12. Openings Keverel Chess Books July – January. Terms & Abbreviations The condition of a book is estimated on the following scale. Each letter can be finessed by a + or - giving 12 possible levels. The judgement will be subjective, of course, but based on decades of experience. F = Fine or nearly new // VG = very good // G = showing acceptable signs of wear. P = Poor, structural damage (loose covers, torn pages, heavy marginalia etc.) but still providing much of interest. AN = Algebraic Notation in which, from White’s point of view, columns are called a – h and ranks are numbered 1-8 (as opposed to the old descriptive system). Figurine, in which piece names are replaced by pictograms, is now almost universal in modern books as it overcomes the language problem. In this case AN may be assumed. pp = number of pages in the book.// ed = edition // insc = inscription – e.g. a previous owner’s name on the front endpaper. o/w = otherwise. dw = Dust wrapper It may be assumed that any book published in Russia will be in the Russian language, (Cyrillic) or an Argentinian book will be in Spanish etc. Anything contrary to that will be mentioned. PB = paperback. SB = softback i.e. a flexible cover that cannot be torn easily. -

Germantown Friends School AFTER-SCHOOL CLUBS

Germantown Friends school DAYExtende PROGRAMd AFTER-SCHOOL CLUBS WINTER 2018 January-March GERMANTOWNFRIENDS.ORG AFTER-SCHOOL CLUBS — WINTER 2018 Please enjoy the following descriptions of the enriching play-centered clubs we have planned for the winter term. All after school clubs will begin the week of January 8, and end during the week of March 5 (with the exception of Friday clubs, which will end on March 2). Make-up classes will take place during the week of March 12. Note: Instrumental Ensembles and Environmental Action Club will be on hiatus during the winter term. GERMANTOWNFRIENDS.ORG 2 >> OBVIOUS CHOICE ATHLETICS 1. All-Star Sports with Coach C. two parts. Part I will be an introduction to and Obvious Choice Athletics ASL taught by Karen Leslie-Henry, Director of Community Outreach for our neighbor, Tuesdays, 3:20-4:20 p.m. (no club 2/20) Pennsylvania School for the Deaf (PSD). Grades 1-5 | $215 Karen will start by teaching the ASL alphabet The All-Star Sports Club with Coach C. and numbers. She will introduce students to and Obvious Choice Athletics offers young basic vocabulary as well as fun activities like athletes the opportunity to play and improve “Silent Snack” and “Silent Games” including their skills in a wide range of sports, including bingo and Uno. In addition, participants will soccer, floor hockey, Ultimate Frisbee, and be introduced to Keith Wann’s video oeuvre dodgeball. In addition to in-depth instruction, as well as the Sign2Me songbook. During the participants hone such important individual spring term, part two of the club will involve skills as eye-hand coordination, strategic a joint program with Lower School students thinking, and sportsmanship all while from PSD. -

Carlsen (13) Mot Kasparov (40)

Carlsen (13) mot Kasparov (40) Foto: Ómar Óskarsson Foto: nr. 2 2004 26. Copenhagen Open Danmarks største åpne internasjonale turnering. POLITIKEN CUP Mulighet for å bo på spillestedet Quality Hotel Politiken Cup 2004 spilles som en åpen 10-runders turnering Høje Tåstrup til rimelige på 9 dager og i en stor gruppe, like fra sterke stormestere til priser. nybegynnere. For steder å bo sjekk: Turneringen spilles fra 24. juli til 1. august 2004 på Quality www.rejse-guide.dk/hoteller/ Hotel Høje Tåstrup, 20 min. fra København. Mer informasjon Registrering ved fram- og online påmelding på www.politikencup.dk møte, lørdag 24. juli mellom 1100 og 1230. Hovedpremier (tusen DKK): Startavgift Betenkningstid: 2 timer 12-10-8-6-4-3-3-4-2-1 GM/IM/FM/WGM/WIM: Gratis på 40 trekk, deretter 1 time Spesialpremier (tusen DKK): Jun. (f. 1984 el. senere): 500 kr. på resten. Ialt 6 timer. Beste kvinne (u/tittel): 2 Seniorer (fylt 65 år): 500 kr. Mulighet for å ta GM- og Beste født e. 1989 (u/tittel): 2 Spillere m/ ELO: 800 kr. IM-napp og få Elo-tall. Spillere u/ ELO: 900 kr. Beste født f. 1939 (u/tittel): 2 Mange deltagende GMer Kr. 100 i tillegg ved påm. e. 1.7. og IMer fra forskjellige land. Ratingpremier kr 2.000: Blant +2600-stormestrene For beste spiller i hver av de Påmelding følgende gruppene: 1000- Lars Bech Hansen er: 1150, 1151-1300, 1301- Hjertebjærgparken 20 Beljavskij, McShane, Heine 1450, 1451-1600, 1601- Kvarmløse, Nielsen, Volkov, Rozentalis 1750, 1751-1900, 1901- DK-4340 Tølløse og Sadvaskov. -

Phronesis and the Participants Perspective

The British Journal of Sociology 2013 Volume 64 Issue 4 Book review symposium: Real Social Science: Applied Phronesis Book Review Symposium on Bent Flyvbjerg, Todd Landman and Sanford Schram (eds) Real Social Science: Applied Phronesis, 2012, CUP, 318 pp. £18.99 (paperback) Phronesis and the participants’ perspective Brian Caterino In Making Social Science Matter (2001), Bent Flyvbjerg proposed a radical challenge to positivistic versions of social inquiry and rational choice. Social inquiry according to Flyvbjerg is not really a ‘science’. The latter, he claimed had roots in the notion of epistemé or what Aristotle viewed as certain and reliable knowledge. Flyvbjerg viewed this type of knowledge as ‘theoretical’. As realized in modern nomological views of science, particulars are subsumed and governed by general laws. In contrast to this nomological version of social inquiry, Flyvbjerg claimed that knowledge of the social world was phronetic in Aristotle’s sense. It is practical, context bound, and independent of theoretical knowledge. Phronesis required the wisdom, insight and skill of an interested participant in social life. Flyvbjerg’s work found a sympathetic ear in the spreading discontent with the rational choice theories and quantitative approaches dominant in major political science journals.Yet such work seemed increasingly irrelevant to their own concerns. For some of us in the Perestroika group, Flyvbjerg’s work provided a way to raise the questions we had about the limits of rational choice theory and exclusively quantitative approaches that emphasized theory build- ing to the neglect of practical life of the participants (Green and Shapiro 1996). Such theories considered the theorist as a neutral or detached observer of social life, and severed the links between social inquiry and the perspectives of the participant in social life. -

Policy and Planning for Large Infrastructure Projects: Problems, Causes, Cures

WPS3781 Public Disclosure Authorized Policy and Planning for Large Infrastructure Projects: Problems, Causes, Cures By Public Disclosure Authorized Bent Flyvbjerg Public Disclosure Authorized World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3781, December 2005 The Policy Research Working Paper Series disseminates the findings of work in progress to encourage the exchange of ideas about development issues. An objective of the series is to get the findings out quickly, even if the presentations are less than fully polished. The papers carry the names of the authors and should be cited accordingly. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the view of the World Bank, its Executive Directors, or the countries they represent. Policy Research Working Papers are available online at http://econ.worldbank.org. Public Disclosure Authorized Page 1 of 32 1. Introduction * For a number of years my research group and I have explored different aspects of the planning of large infrastructure projects (Flyvbjerg, Bruzelius, and Rothengatter, 2003; Flyvbjerg, Holm, and Buhl, 2002, 2004, 2005; Flyvbjerg and Cowi, 2004; Flyvbjerg, 2005a, 2005b).1 In this paper I would like to take stock of what we have learned from our research so far. First I will argue that a major problem in the planning of large infrastructure projects is the high level of misinformation about costs and benefits that decision makers face in deciding whether to build, and the high risks such misinformation generates. Second I will explore the causes of misinformation and risk, mainly in the guise of optimism bias and strategic misrepresentation. -

How (In)Accurate Are Demand Forecasts in Public Works Projects? Forecasted Traffic

How (In)accurate Are This article presents results from the first statistically significant study of traffic Demand Forecasts in forecasts in transportation infrastructure projects. The sample used is the largest of its kind, covering projects in Public Works Projects? nations worth U.S.$ billion. The study shows with very high statistical signifi- cance that forecasters generally do a poor job of estimating the demand for trans- portation infrastructure projects. For The Case of Transportation out of rail projects, passenger forecasts are overestimated; the average overestima- tion is %. For half of all road projects, Bent Flyvbjerg, Mette K. Skamris Holm, and Søren L. Buhl the difference between actual and fore- casted traffic is more than ±%. The result is substantial financial risks, which are typically ignored or downplayed by planners and decision makers to the det- espite the enormous sums of money being spent on transportation riment of social and economic welfare. infrastructure, surprisingly little systematic knowledge exists about the Our data also show that forecasts have not costs, benefits, and risks involved. The literature lacks statistically valid become more accurate over the -year D answers to the central and self-evident question of whether transportation infra- period studied, despite claims to the con- structure projects perform as forecasted. When a project underperforms, this is trary by forecasters. The causes of inaccu- racy in forecasts are different for rail and often explained away as an isolated instance of unfortunate circumstance; it is road projects, with political causes playing typically not seen as the particular expression of a general pattern of underper- a larger role for rail than for road.