Book Review Feminist Scripts for Punishment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RAPE MYTHS in the LOCAL and NATIONAL NEWSPAPER COVERAGE of the BROCK TURNER CASE by Juana Campos a Thesis Submitted to the Depar

Running head: RAPE MYTHS IN THE NEWSPAPER COVERAGE OF THE BROCK TURNER CASE RAPE MYTHS IN THE LOCAL AND NATIONAL NEWSPAPER COVERAGE OF THE BROCK TURNER CASE by Juana Campos A thesis submitted to the Department of Sociology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Sociology Chair of Committee: Samantha S. Kwan, Ph.D. Committee Member: Amanda Baumle, Ph.D. Committee Member: Jennifer Arney, Ph.D. University of Houston December 2020 RAPE MYTHS IN THE NEWSPAPER COVERAGE OF THE BROCK TURNER CASE Copyright 2020, Juana Campos ii RAPE MYTHS IN THE NEWSPAPER COVERAGE OF THE BROCK TURNER CASE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I would like to thank my committee chair, Dr. Samantha Kwan not only for her expertise and feedback but also for her understanding, empathy, and support during rough times. Without her guidance, I don’t think I could have pushed through to finish these last steps in my thesis. Additionally, I would like to thank Dr. Amanda Baumle and Dr. Jennifer Arney for their time, patience, and feedback. For funding, I would like to thank the Department of Women and Gender Studies for awarding me the Blanche Epsy Chenoweth Graduate Fellowship. I would also like to the Department of Sociology for awarding me their Department Research Grant. Their funding made it possible for me to fund my education and the additional coder. Last but certainly not least, I am thankful for the generous support from my friends and family. Thank you for lending me your wifi and your support. iii RAPE MYTHS IN THE NEWSPAPER COVERAGE OF THE BROCK TURNER CASE ABSTRACT Rape myths are false claims that pardon perpetrators, blame victims, and justify sexual assault. -

From Carceral Feminism to Transformative Justice: Women-Of-Color Feminism and Alternatives to Incarceration

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325457894 From carceral feminism to transformative justice: Women-of-color feminism and alternatives to incarceration Article in Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work · May 2018 DOI: 10.1080/15313204.2018.1474827 CITATIONS READS 0 138 1 author: Mimi E. Kim California State University, Long Beach 14 PUBLICATIONS 54 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Crime and Welfare Polices View project All content following this page was uploaded by Mimi E. Kim on 09 October 2018. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work ISSN: 1531-3204 (Print) 1531-3212 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/wecd20 From carceral feminism to transformative justice: Women-of-color feminism and alternatives to incarceration Mimi E. Kim To cite this article: Mimi E. Kim (2018) From carceral feminism to transformative justice: Women- of-color feminism and alternatives to incarceration, Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 27:3, 219-233, DOI: 10.1080/15313204.2018.1474827 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/15313204.2018.1474827 Published online: 30 May 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 21 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=wecd20 JOURNAL OF ETHNIC & CULTURAL DIVERSITY IN SOCIAL WORK 2018, VOL. 27, NO. 3, 219–233 https://doi.org/10.1080/15313204.2018.1474827 From carceral feminism to transformative justice: Women-of-color feminism and alternatives to incarceration Mimi E. -

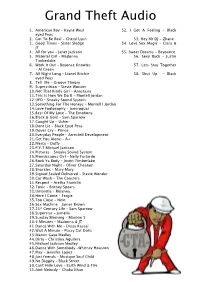

GTA Song List.Pages

Grand Theft Audio 1. American Boy – Kayne West 52. I Got A Feeling – Black eyed Peas 2. Got To Be Real – Cheryl Lynn 53. Hey Mr DJ - Zhane 3. Good Times – Sister Sledge 54. Love Sex Magic – Ciara & JT 4. All for you – Janet Jackson 55. Sweet Dreams - Beyounce 5. Material Girl – Madonna 56. Sexy Back – Justin Timberlake 6. Work It Out – Beyonce Knowles 57. Lets Stay Together – Al Green 7. All Night Long – Lionel Ritchie 58. Shut Up - Black eyed Peas 8. Tell Me – Groove Theory 9. Superstition – Stevie Wonder 10.Not That Kinda Girl – Anastasia 11.This Is How We Do It – Montell Jordan 12.UFO – Sneaky Sound System 13.Something For The Honeys – Montell l Jordan 14.Love Foolosophy – Jamiroquai 15.Best Of My Love – The Emotions 16.Black & Gold – Sam Sparrow 17.Caught Up – Usher 18.Dont Lie – Black Eyed Peas 19.Doves Cry – Prince 20.Everyday People – Arrested Development 21.Get You Alone – A+ 22.Mercy – Dufy 23.P.Y.T Michael Jackson 24.Pictures – Sneaky Sound System 25.Promiscuous Girl – Nelly Furtardo 26.Rock Ya Body – Justin Timberlake 27.Saturday Night – Oliver Cheatam 28.Shackles – Mary Mary 29.Signed Sealed Delivered – Stevie Wonder 30.Car Wash – The Coasters 31.Respect – Aretha Franklin 32.Toxic – Britney Spears 33.Umbrella – Rhianna 34.Here I Come – Fergie 35.Too Close – Next 36.Sex Machine – James Brown 37.21st Century Life – Sam Sparrow 38.Superstar - Jamelia 39.Sunday Morning – Maroon 5 40.4 Minutes – Madonna & JT 41.Dance With Me – Dizzy Rascal 42.Wait A Minute – Pussy Cat Dolls 43.Marvin Gaye Medley 44.Dirty – Christina Aguilera 45.Michael Jackson Medley 46.Dance With Somebody –Whitney Houston 47.Play – Jennifer Lopez 48.Just friends – Musique Soul Child 49.No Diggity – Black Street 50.Cant Hide Love – Earth Wind & Fire 51.Aint Nobody – Chaka Khan. -

Excavating the Sex Discrimination Roots of Campus Sexual Assault

Pittsburgh University School of Law Scholarship@PITT LAW Articles Faculty Publications 2017 Back to Basics: Excavating the Sex Discrimination Roots of Campus Sexual Assault Deborah Brake University of Pittsburgh School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.pitt.edu/fac_articles Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Education Law Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Higher Education Administration Commons, Law and Gender Commons, and the Sexuality and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Deborah Brake, Back to Basics: Excavating the Sex Discrimination Roots of Campus Sexual Assault, 6 Tennessee Journal of Race, Gender & Social Justice 7 (2017). Available at: https://scholarship.law.pitt.edu/fac_articles/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship@PITT LAW. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@PITT LAW. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. BACK TO BASICS: EXCAVATING THE SEX DISCRIMINATION ROOTS OF CAMPUS SEXUAL ASSAULT Deborah L. Brake* Introduction ............................................................................................................. 7 I. Liberal Feminism and Women’s Leadership Meet Dominance Feminism and Sexual Subordination ....................................................................................... 9 II. The Gender-Blind Discourses of Campus Sexual Assault ............................ -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Hierarchical Sisterhood for Ella & Denni

Hierarchical Sisterhood For Ella & Denni and in loving memory of Sadeta Vladavić (1959–1992) Moje duboko ubeđenje je da su žene svih generacija, u svom vremenu sa svim njegovim i svojim vlastitim ograničenjima, uradile što je bilo moguće. It is my deep conviction that women of all generations did what was possible, within their own limits and within the limits of their times. Historian Neda Božinović Örebro Studies in History 19 SANELA BAJRAMOVIĆ Hierarchical Sisterhood Supporting Women's Peacebuilding through Swedish Aid to Bosnia and Herzegovina 1993–2013 Cover illustration: Vladimir Tenjer Maps: Courtesy of the United Nations Pictures: Courtesy of Kvinna till Kvinna © Sanela Bajramović, 2018 Title: Hierarchical Sisterhood. Supporting Women's Peacebuilding through Swedish Aid to Bosnia and Herzegovina 1993–2013 Publisher: Örebro University 2018 www.oru.se/publikationer-avhandlingar Print: Örebro University, Repro 09/2018 ISSN 1650-2418 ISBN 978-91-7529-258-8 Abstract Sanela Bajramović (2018). Hierarchical Sisterhood. Supporting Women’s Peace- building through Swedish Aid to Bosnia and Herzegovina 1993–2013, Örebro Studies in History 19, 322 pages. This dissertation examines possibilities and challenges faced by interna- tional interveners in a post-socialist and violently divided area. The study object is the Swedish foundation Kvinna till Kvinna, formed in 1993 during the Bosnian war, originating from the peace movement and supported by the Swedish government aid agency Sida. The aim is to contextualize and analyze Kvinna till Kvinna’s two decades of engage- ment in peacebuilding in Bosnia. The encounter with domestic women’s NGOs is of particular interest. By focusing on rhetoric, practice and silences, the ambition has been to understand the international/local relationship from the perspective of both actors. -

Benevolent Feminism and the Gendering of Criminality: Historical and Ideological Constructions of US Women's Prisons

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2020 Benevolent Feminism and the Gendering of Criminality: Historical and Ideological Constructions of US Women's Prisons Emma Stammen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Benevolent Feminism and the Gendering of Criminality: Historical and Ideological Constructions of US Women’s Prisons By Emma Stammen Submitted to Scripps College in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree of Bachelor of Arts Professor Piya Chatterjee Professor Jih-Fei Cheng December 13, 2019 Acknowledgements I would like to express my deep gratitude to Professor Piya Chatterjee for advising me throughout my brainstorming, researching, and writing processes, and for her thoughtful and constructive feedback. Professor Chatterjee took the time to set up calls with me during the summer while I was researching in New York, and met with me consistently throughout the semester to make timelines, talk through ideas, and workshop chapters. Being able to work closely with Professor Chatterjee has been an incredible experience, as she not only made the thesis writing process more enjoyable, but also challenged me to push my analysis further. I would also like to thank Professor Jih-Fei Cheng, who has been my advisor since my first year. He has provided me with guidance not only throughout my thesis writing process, but also my time at Scripps. Professor Cheng helped me talk through ideas and sections I was struggling with, and provided me with amazing recommendations for work to turn to in order to support my thesis. -

The Evolution of Feminist and Institutional Activism Against Sexual Violence

Bethany Gen In the Shadow of the Carceral State: The Evolution of Feminist and Institutional Activism Against Sexual Violence Bethany Gen Honors Thesis in Politics Advisor: David Forrest Readers: Kristina Mani and Cortney Smith Oberlin College Spring 2021 Gen 2 “It is not possible to accurately assess the risks of engaging with the state on a specific issue like violence against women without fully appreciating the larger processes that created this particular state and the particular social movements swirling around it. In short, the state and social movements need to be institutionally and historically demystified. Failure to do so means that feminists and others will misjudge what the costs of engaging with the state are for women in particular, and for society more broadly, in the shadow of the carceral state.” Marie Gottschalk, The Prison and the Gallows: The Politics of Mass Incarceration in America, p. 164 ~ Acknowledgements A huge thank you to my advisor, David Forrest, whose interest, support, and feedback was invaluable. Thank you to my readers, Kristina Mani and Cortney Smith, for their time and commitment. Thank you to Xander Kott for countless weekly meetings, as well as to the other members of the Politics Honors seminar, Hannah Scholl, Gideon Leek, Cameron Avery, Marah Ajilat, for your thoughtful feedback and camaraderie. Thank you to Michael Parkin for leading the seminar and providing helpful feedback and practical advice. Thank you to my roommates, Sarah Edwards, Zoe Guiney, and Lucy Fredell, for being the best people to be quarantined with amidst a global pandemic. Thank you to Leo Ross for providing the initial inspiration and encouragement for me to begin this journey, almost two years ago. -

MIAMI UNIVERSITY the Graduate School

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Bridget Christine Gelms Candidate for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ______________________________________ Dr. Jason Palmeri, Director ______________________________________ Dr. Tim Lockridge, Reader ______________________________________ Dr. Michele Simmons, Reader ______________________________________ Dr. Lisa Weems, Graduate School Representative ABSTRACT VOLATILE VISIBILITY: THE EFFECTS OF ONLINE HARASSMENT ON FEMINIST CIRCULATION AND PUBLIC DISCOURSE by Bridget C. Gelms As our digital environments—in their inhabitants, communities, and cultures—have evolved, harassment, unfortunately, has become the status quo on the internet (Duggan, 2014 & 2017; Jane, 2014b). Harassment is an issue that disproportionately affects women, particularly women of color (Citron, 2014; Mantilla, 2015), LGBTQIA+ women (Herring et al., 2002; Warzel, 2016), and women who engage in social justice, civil rights, and feminist discourses (Cole, 2015; Davies, 2015; Jane, 2014a). Whitney Phillips (2015) notes that it’s politically significant to pay attention to issues of online harassment because this kind of invective calls “attention to dominant cultural mores” (p. 7). Keeping our finger on the pulse of such attitudes is imperative to understand who is excluded from digital publics and how these exclusions perpetuate racism and sexism to “preserve the internet as a space free of politics and thus free of challenge to white masculine heterosexual hegemony” (Higgin, 2013, n.p.). While rhetoric and writing as a field has a long history of examining myriad exclusionary practices that occur in public discourses, we still have much work to do in understanding how online harassment, particularly that which is gendered, manifests in digital publics and to what rhetorical effect. -

'Acting Like 13 Year Old Boys?'

‘Acting like 13 year old boys?’ Exploring the discourse of online harassment and the diversity of harassers Lucy Fisher-Hackworth Submitted to the Department of Gender Studies, University of Utrecht In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Erasmus Mundus Master's Degree in Women's and Gender Studies Main supervisor: Dr.Domitilla Olivieri (University of Utrecht) Second reader: Dr. Jasmina Lukic (Central European University) Utrecht, the Netherlands 2016 Approved: _________________________________________ 1 ABSTRACT In this thesis, I have undertaken research into the users behind online harassment. The impetus behind this was to investigate taken for granted assumptions about who harassers are, what they do online, and how they do it. To begin, I highlight the discourse of online harassment of women in scholarship and online-news media, discussing the assumptions made about who is harassing and why. I discuss the lack of consideration of multi-layered harassment and argue for more research that takes into consideration the intersectionality of harassing content, and the experiences of all women online. I provide an overview of online methodologies and of feminism on the internet. I then undertake an investigation into harassers behind online harassment of women, and find trends in user profiles, user behaviour, and in online communication patterns more broadly. I discuss how researching this topic affected me personally, reflecting on the impact of viewing high amounts abusive content. My findings challenged many of the assumptions initially identified, so, with that in mind, I provide a discussion of why such assumptions are problematic. I argue that such assumptions contribute to a discourse that homogenizes harassment and harassers, and overlooks broader internet-specific behaviours. -

NOW WAP's WHAT I CALL MUSIC! Submitted By: Immediate Future Friday, 20 January 2006

NOW WAP'S WHAT I CALL MUSIC! Submitted by: Immediate Future Friday, 20 January 2006 EMI Music UK puts pop stars in your pocket with launch of mobile music store wap.the-raft.com bringing together music downloads, ringtones & videos from EMI Records, Virgin Records, Parlophone, Angel and Catalogue - http://wapinfo.the-raft.com Calling all music fans… Fancy going home with a Brit tonight? EMI Music UK extends ‘The Raft’ online music store from web to mobile with the launch of its mobile music site (http://wapinfo.the-raft.com). By texting ‘GO RAFT’ to 85080 (free text from all networks), music lovers will be able to access official artist news, breaking tour dates, music downloads and video, competitions and artist approved ringtones and realtones. And if you’ve got a bit of a creative urge yourself, you’ll be able to customise your own tracks by adding beats or special features to turn them into personalised ringtones (http://wapinfo.the-raft.com). Be the envy of all your friends with your totally exclusive ringtones! You’ll be kept up to date with the latest news and featured artist areas which include Artist A-Zs and weekly competitions in anyone of the following categories; pop, urban, dance, jazz and rock. Wap.the-raft.com (http://wapinfo.the-raft.com) will also host the UK top 10 ringtones plus specialist charts like alternative and Bollywood. Competitions include money-can’t-buy exclusive artist merchandise plus album collections—such as the Brits collection; a bumper hamper of Brits-nominated albums Wap.the-raft.com provides something for every music fan—in an easy-to-find mobile music format. -

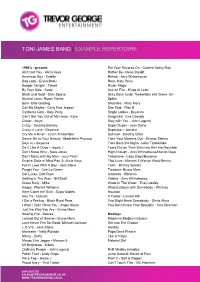

Toni James Band | Example Repertoire

TONI JAMES BAND | EXAMPLE REPERTOIRE 1990’s - present Put Your Records On - Corrine Bailey Ray Ain’t Got You - Alicia Keys Rather Be- Clean Bandit American Boy - Estelle Rehab - Amy Whinehouse Bag Lady - Eryka Badu Roar- Katy Perry Boogie Tonight - Tweet Rude- Magic By Your Side - Sade Sex on Fire - Kings of Leon Black and Gold - Sam Sparro Sexy Back Justin Timberlake into Grove Jet - Blurred Lines- Robin Thicke Spiller Burn- Ellie Golding Shackles - Mary Mary Call Me Maybe - Carly Rae Jepson She Said - Plan B California Girls - Katy Perry Single Ladies - Beyonce Can’t Get You Out of My Head - Kylie Song Bird - Eva Cassidy Closer - Neyo Stay with You - John Legend Crazy - Gnarles Barkley Super Duper - Joss Stone Crazy in Love - Beyonce Superstar - Jamelia Cry Me A River - Justin Timberlake Survivor - Destiny Child Dance Me to Your Beauty - Madeleine Peyroux Take Your Mamma Out - Scissor Sisters Deja vu - Beyonce Take Back the Night- Justin Timberlake Do It Like A Dude - Jessie J Tears Dry on Their Own into Ain’t No Mountain Don’t Know Why - Nora Jones High Enough - Amy Whinehouse/Marvin Gaye Don’t Mess with My Man - Lucy Pearl Telephone - Lady Gaga/Beyonce Empire State of Mind Part 2- Alicia Keys This Love - Maroon 5 (Kanye West Remix) Fell in Love With A Boy - Joss Stone Toxic - Britney Spears Forget You - Cee Lo Green Treasure- Bruno Mars Get Lucky- Daft Punk Umbrella - Rihanna Getting in The Way - Gill Scott Valerie - Amy Whinehouse Grace Kelly - Mika Wade in The Water - Eva Cassidy Happy- Pharrell Williams Wanna Dance with Somebody