The Vertical Limit of State Sovereignty, 72 J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Runway Safety Spring 2021 Report

Graphical NOTAM Interface For Improving Efficiency of Reporting NOTAM Information April 2021 Design Challenge: Runway Safety/Runway Incursions/Runway Excursions Challenge E: Optimizing application of NextGen technology to improve runway safety in particular and airport safety in general. Team Members: Undergraduate Students: Matthew Bacon, Gregory Porcaro, Andrew Vega Advisor’s Name: Dr. Audra Morse Michigan Technological University Table of Contents | 1 02 Executive Summary Runway excursions are a type of aviation incident where an aircraft makes an unsafe exit from the runway. According to the Ascend World Aircraft Accident Summary (WAAS), 141 runway excursion accidents involving the Western-built commercial aircraft fleet occurred globally from 1998 to 2007, resulting in 550 fatalities; 74% of landing phase excursions were caused by either weather-related factors or decision-making factors (Ascend, 2007). One mitigation strategy is training pilots how to interpret Runway Condition Codes (RWYCCs) to understand runway conditions. Recent developments such as NextGen and Electronic Flight Bags (EFBs) have improved the quality of weather condition reporting. However, Notices to Airmen (NOTAMs), the primary source of runway condition information and any other irregularities in airspace, are still presented to pilots in an inefficient format contributing to runway excursions and safety concerns NOTAMs consist of confusing abbreviations and do not effectively convey the relative importance of information. The team developed an Electronic Flight Bag (EFB) user interface that provides a graphical representation of NOTAM and weather information to improve how pilots receive condition changes at airports. The graphical NOTAM interface utilizes Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B) to receive real time NOTAM updates. -

Advanced Concept of the National Airspace System of 2015: Human Factors Considerations For

Advanced Concept of the National Airspace System of 2015: Human Factors Considerations for Air Traffic Control Ben Willems, Human Factors Team – Atlantic City, ATO-P Anton Koros, Northrop Grumman Information Technology June 2007 DOT/FAA/TC-TN-07/21 This document is available to the public through the National Technical Information Service (NTIS), Springfield, VA 22161. A copy is retained for reference at the William J. Hughes Technical Center Library. U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration William J. Hughes Technical Center Atlantic City International Airport, NJ 08405 ote technical note NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers' names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. This document does not constitute Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) certification policy. Consult your local FAA aircraft certification office as to its use. This report is available at the FAA, William J. Hughes Technical Center’s full-text Technical Reports Web site: http://actlibrary.tc.faa.gov in Adobe® Acrobat® portable document format (PDF). Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. DOT/FAA/TC-TN-07/21 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Advanced Concept of the National Airspace System of 2015: Human Factors June 2007 Considerations for Air Traffic Control 6. Performing Organization Code AJP-6110 7. -

Rethinking East Mediterranean Security: Powers, Allies & International Law

Touro Law Review Volume 33 Number 3 Article 10 2017 Rethinking East Mediterranean Security: Powers, Allies & International Law Sami Dogru Herbert Reginbogin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Dogru, Sami and Reginbogin, Herbert (2017) "Rethinking East Mediterranean Security: Powers, Allies & International Law," Touro Law Review: Vol. 33 : No. 3 , Article 10. Available at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol33/iss3/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Touro Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dogru and Reginbogin: Rethinking East Mediterranean Security RETHINKING EAST MEDITERRANEAN SECURITY: POWERS, ALLIES & INTERNATIONAL LAW Sami Dogru * Herbert Reginbogin ** Contents Abstract I. Introduction II. Overview to Reduce Tensions in Eastern Mediterranean and Southeast Asia III. The Need for Maritime Delimitation IV. The Laws of Maritime Delimitation V. Tension Rising in the South and East China Seas VI. The Eastern Mediterranean Conundrum of Territorial Disputes VII. Reaction by the Republic of Turkey - Escalation of Tension VIII. Reaction by the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC)—Escalation of Tension IX. USA, Russia, China, and Turkey’s Shift in Eastern Mediterranean Geopolitics – Rising Tensions X. Case for an Eastern Mediterranean Delimitation Program A.Relevant Area B.Configuration of the Coasts C.Proportionality D.Islands 1.Islands ‘On the Wrong Side’ 2.Island State E. Security and Navigation Factors F.Economic Factors: Joint Maritime Development Regime 1.The Characteristics of a Joint Maritime Development Regime 2.Designing a Joint Development Area 3.Maritime Joint Development Regime XI. -

Freedom of Navigation in the South China Sea a Practical Guide

Freedom of Navigation in the South China Sea A Practical Guide Eleanor Freund SPECIAL REPORT JUNE 2017 Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.belfercenter.org Publication design and illustrations by Andrew Facini Cover photo: United States. Central Intelligence Agency. The Spratly Islands and Paracel Islands. Scale 1:2,000,000. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency, 1992. Copyright 2017, President and Fellows of Harvard College Printed in the United States of America Freedom of Navigation in the South China Sea A Practical Guide Eleanor Freund SPECIAL REPORT JUNE 2017 About the Author Eleanor Freund is a Research Assistant at Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. She studies U.S. foreign policy and security issues, with a focus on U.S.-China relations. Email: [email protected] Acknowledgments The author is grateful to James Kraska, Howard S. Levie Professor of International Law at the U.S. Naval War College, and Julian Ku, Maurice A. Deane Distinguished Professor of Constitutional Law at Hofstra University School of Law, for their thoughtful comments and feedback on the text of this document. All errors or omissions are the author’s own. ii Freedom of Navigation in the South China Sea: A Practical Guide Table of Contents What is the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)? ..............1 What are maritime features? ......................................................................1 Why is the distinction between different maritime features important? .................................................................................... 4 What are the territorial sea, the contiguous zone, and the exclusive economic zone? ........................................................... 5 What maritime zones do islands, rocks, and low-tide elevations generate? ....................................................................7 What maritime zones do artificially constructed islands generate? .... -

Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) in the Light of Public International Law

Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) in the light of Public International Law Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) in the light of Public International Law ZOLTÁN PAPP Phd Student, Pázmány Péter Catholic University, In-house legal counsel, HungaroControl Pte Ltd. Co.* The Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) is established to serve the national security interests of the state. Maintaining ADIZ becomes fundamentally relevant from the perspective of international law when such a zone extends into airspace suprajacent to international waters. Materially, two considerations are most relevant in terms of ADIZ conforming to international law, both potentially creating a conflict with ADIZ rules: Contracting Parties to the Chicago Convention on International Civil Aviation have delegated rule-making powers to enact rules of the air with a view to safeguarding the safety of air traffic in international airspace to the ICAO Council. Furthermore, in international airspace the state of registry generally enjoys exclusive jurisdiction with respect to the aircraft carrying its national mark. In this paper ADIZ will be deemed as exercising jurisdiction over extraterritorial acts by the state maintaining ADIZ; hence, the prescriptive and enforcement distinction adds an additional layer to the analysis of the international legal context of ADIZ. The response to as to how ADIZ fits in the international legal framework may differ depending on whether one seeks to identify permissive rules of international law related to the maintenance of ADIZ in international airspace or the non-existence of prohibitive rules sufficient to justify conformance with international law. Keywords: ADIZ, air law, law of the sea, Chicago Convention on International Civil Aviation, jurisdiction, use of force, international customary law, civil aircraft, state of registry 1. -

Jurisdictional Waters in the Mediterranean and Black Seas

DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES STRUCTURAL AND COHESION POLICIESB POLICY DEPARTMENT AgricultureAgriculture and Rural and Development Rural Development STRUCTURAL AND COHESION POLICIES B CultureCulture and Education and Education Role The Policy Departments are research units that provide specialised advice Fisheries to committees, inter-parliamentary delegations and other parliamentary bodies. Fisheries RegionalRegional Development Development Policy Areas TransportTransport and andTourism Tourism Agriculture and Rural Development Culture and Education Fisheries Regional Development Transport and Tourism Documents Visit the European Parliament website: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/studies PHOTO CREDIT: iStock International Inc., Photodisk, Phovoir DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT B: STRUCTURAL AND COHESION POLICIES FISHERIES JURISDICTIONAL WATERS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN AND BLACK SEAS STUDY This document has been requested by the European Parliament’s Committee on Fisheries. AUTHORS Prof. Juan Luis Suárez de Vivero TECHNICAL TEAM Mrs Inmaculada Martínez Alba Mr Juan Manuel Martín Jiménez Mrs Concepción Jiménez Sánchez ADMINISTRATOR Mr Jesús Iborra Martín Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies European Parliament E-mail: [email protected] EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Mrs Virginija Kelmelyté LANGUAGE VERSIONS Original: ES Translations: DE, EN, FR, IT. ABOUT THE PUBLISHER To contact the Policy Department or subscribe to its monthly bulletin, write to [email protected] Manuscript completed in December 2009. Brussels, © European Parliament, 2009 This document is available from the following website: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/studies DISCLAIMER The opinions given in this document are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the European Parliament. -

Coastal State's Jurisdiction Over Foreign Vessels

Pace International Law Review Volume 14 Issue 1 Spring 2002 Article 2 April 2002 Coastal State's Jurisdiction over Foreign Vessels Anne Bardin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/pilr Recommended Citation Anne Bardin, Coastal State's Jurisdiction over Foreign Vessels, 14 Pace Int'l L. Rev. 27 (2002) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/pilr/vol14/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace International Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES COASTAL STATE'S JURISDICTION OVER FOREIGN VESSELS Anne Bardin I. Introduction ....................................... 28 II. The Rights and Duties of States in the Different Sea Zones Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea ............................. 30 A. Internal W aters ............................... 30 1. Jurisdiction Over Foreign Merchant V essels ..................................... 30 2. Jurisdiction Over Foreign Warships ....... 31 3. The Right of all Vessels to Free Access to P ort ........................................ 32 B. The Territorial Sea ............................ 33 1. Innocent Passage in the Territorial Sea .... 34 2. Legislative Competence of the Coastal State ....................................... 35 3. Implementation of its Legislation by the Coastal State .............................. 36 4. Criminal Jurisdiction of the Coastal State ....................................... 37 5. W arships .................................. 39 C. The Contiguous Zone .......................... 39 D. The Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) ........... 40 1. Rights of the Coastal State in its EEZ ..... 41 2. Artificial Islands and Scientific Research .. 41 3. Rights of Foreign States in the EEZ ....... 43 4. -

Investigation Into Unmanned Aircraft System Incidents in the National Airspace System

International Journal of Aviation, Aeronautics, and Aerospace Volume 3 Issue 4 Article 2 11-2-2016 Investigation into Unmanned Aircraft System Incidents in the National Airspace System Rohan S. Sharma Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/ijaaa Part of the Aviation Safety and Security Commons, and the Management and Operations Commons Scholarly Commons Citation Sharma, R. S. (2016). Investigation into Unmanned Aircraft System Incidents in the National Airspace System. International Journal of Aviation, Aeronautics, and Aerospace, 3(4). https://doi.org/10.15394/ ijaaa.2016.1146 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Aviation, Aeronautics, and Aerospace by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sharma: Investigation Into Unmanned Aircraft Incidents The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) forecasts the sale of commercial and hobbyist Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS) to rise from 2.5 million to 7 million USD in the timeframe of 2016 – 2020 (Federal Aviation Administration, 2016). A status report in March from the FAA revealed that more than 4,000 exemptions were issued to insurers, individuals, or commercial organizations in order to operate commercially registered UASs’ in the National Airspace System (NAS) under Section 333 authority of the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012. Additionally, over 408,000 UASs’ have been registered (Federal Aviation Administration, 2016). The UAS market will continue to be the most dynamic growth sector within aviation (Federal Aviation Administration, 2016). -

Guidelines for Marine Protected Areas

Guidelines for Marine Protected Areas World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA) Guidelines for Marine MPAs are needed in all parts of the world – but it is vital to get the support Protected Areas of local communities Edited and coordinated by Graeme Kelleher Adrian Phillips, Series Editor IUCN Protected Areas Programme IUCN Publications Services Unit Rue Mauverney 28 219c Huntingdon Road CH-1196 Gland, Switzerland Cambridge, CB3 0DL, UK Tel: + 41 22 999 00 01 Tel: + 44 1223 277894 Fax: + 41 22 999 00 15 Fax: + 44 1223 277175 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No. 3 IUCN The World Conservation Union The World Conservation Union CZM-Centre These Guidelines are designed to be used in association with other publications which cover relevant subjects in greater detail. In particular, users are encouraged to refer to the following: Case studies of MPAs and their Volume 8, No 2 of PARKS magazine (1998) contributions to fisheries Existing MPAs and priorities for A Global Representative System of Marine establishment and management Protected Areas, edited by Graeme Kelleher, Chris Bleakley and Sue Wells. Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, The World Bank, and IUCN. 4 vols. 1995 Planning and managing MPAs Marine and Coastal Protected Areas: A Guide for Planners and Managers, edited by R.V. Salm and J.R. Clark. IUCN, 1984. Integrated ecosystem management The Contributions of Science to Integrated Coastal Management. GESAMP, 1996 Systems design of protected areas National System Planning for Protected Areas, by Adrian G. Davey. Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No. -

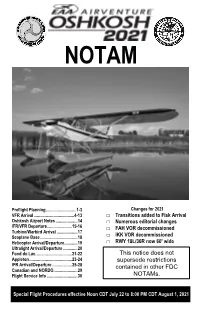

2021 EAA Airventure NOTAM

NOTAM Preflight Planning ............................ 1-3 Changes for 2021 VFR Arrival ..................................... 4-13 □ Transitions added to Fisk Arrival Oshkosh Airport Notes .................... 14 □ Numerous editorial changes IFR/VFR Departure ....................... 15-16 □ FAH VOR decommissioned Turbine/Warbird Arrival ................... 17 Seaplane Base .................................. 18 □ IKK VOR decommissioned Helicopter Arrival/Departure ............ 19 □ RWY 18L/36R now 60' wide Ultralight Arrival/Departure ............. 20 Fond du Lac. ................................ 21-22 This notice does not Appleton ....................................... 23-24 supersede restrictions IFR Arrival/Departure .................. 25-28 contained in other FDC Canadian and NORDO ...................... 29 Flight Service Info ............................ 30 NOTAMs. Special Flight Procedures effective Noon CDT July 22 to 8:00 PM CDT August 1, 2021 Preflight Planning For one week each year, EAA AirVenture OSH Aircraft Parking Oshkosh has the highest concentration of • Separate aircraft parking areas are used at aircraft in the world. Your careful reading and OSH for different types of aircraft. Parking adherence to the procedures in this NOTAM for show planes (experimental, warbird, are essential to maintaining the safety record rotorcraft, amphibian, and production of this event. Flight planning should include aircraft manufactured prior to 1971) has thorough familiarity with NOTAM procedures, generally been available throughout EAA -

Bulletin No. 91 The

Bulletin No. 91 Law of the Sea Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea Office of Legal Affairs United Nations Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea Office of Legal Affairs Law of the Sea Bulletin No. 91 United Nations New York, 2017 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the ex- pression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The texts of treaties and national legislation contained in the Bulletin are reproduced as submitted to the Secretariat, without formal editing. Furthermore, publication in the Bulletin of information concerning developments relating to the law of the sea emanating from actions and decisions taken by States does not imply recognition by the United Na- tions of the validity of the actions and decisions in question. IF ANY MATERIAL CONTAINED IN THE BULLETIN IS REPRODUCED IN PART OR IN WHOLE, DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT SHOULD BE GIVEN. United Nations Publication ISBN 978-92-1-133855-3 Copyright © United Nations, 2017 All rights reserved Printed at the United Nations, New York ContentS Page I. UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION ON THE LAW OF THE SEA Status of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, of the Agreement relating to the Implementation of Part XI of the Convention and of the Agreement for the Implementation of the Provisions of the Convention relating to the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks 1. -

UNDP-GEF International Waters Programme – Delivering Results

������ International Waters Programme – Delivering results - FOTOLIA TEINBERG S RANCK © F GEFGEF UNDP-GEF International Waters Team: Abdoulaye Ndiaye (C/W Africa) [email protected] Mirey Atallah (Arab States) [email protected] Nik Sekhran (S & E Africa marine & coastal) [email protected] Akiko Yamamoto (S & E Africa freshwater) [email protected] Anna Tengberg (Asia-Pacific) [email protected] Vladimir Mamaev (E & C Europe and CIS) [email protected] Juerg Staudenmann (E & C Europe and CIS) [email protected] Paula Caballero (Latin America & Caribbean) [email protected] Andrew Hudson (Global) [email protected] UNDP-GEF International Waters Programme – Delivering Results For over 15 years, through its International Waters portfolio, UNDP-GEF has been providing support to assist over 100 countries in working jointly to identify, prioritize, understand, and address the key transboundary environmental and water resources issues of some of the world’s largest and most significant shared waterbodies. This publication highlights the many important results delivered to date by UNDP-GEF’s International Waters programme, including: • Preparation and ministerial level adoption of 11 Strategic Action Programmes outlining national and regional commitments to governance reforms and investments; seven SAPs are now under implementation; • Preparation and adoption of four regional waterbody legal agreements, some of which have already come into force – Lake Tanganyika, Pacific Fisheries, Caspian Sea (with