Analyzing the Adaptive Reuse of Historic Churches As Craft Breweries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November and December Newsletter

Frank B. Fuhrer Wholesale Company 11/01/2019 Issue : 6 November and December Newsletter Inside this issue: Coors Light’s Viral “Made to Chill” Campaign is Moving the Needle New CMO’s Insightful Ads Speak Directly to Millennials YUENGLING /IMPORT/ 1-5 SPECIALTY EVERDAY The new campaign, Made to Chill, repositions Coors Light as the “ideal antidote to an PACKAGES always-on world.” The campaign portrays millennials actively seeking ways to take a YUENGLING /IMPORT/ 6-11 mental break from lives spent, “always being on and connected, which can be SPECIALTY DIVISION SEASONAL OFFERINGS all-consuming and overwhelming,” says Ryan Reis, vice president of the Coors family of brands. “We’re trying to give them a moment to chill.” ANHEUSER-BUSCH 12-13 DIVISION SEASONAL The ads, currently airing on streaming services and channels like ESPN, feature everyday OFFERINGS occasions where young people reach for a cold Coors Light when they need a time-out COORS/DIAGEO/BOSTON 14 from their day to chill. One spot that went viral earlier this month features a young DIVISION EVERYDAY PACKAGES professional woman returning to her apartment after a long day at work, cracking open a Coors Light. While relaxing on her couch she effortlessly removes her bra (through her COORS/DIAGEO/BOSTON 15-19 DIVISION SEASONAL shirt sleeve) and tosses it aside. OFFERINGS More ads featuring moments to chill are on the way, as is a revamped social media BREWERY NEWS 20-23 presence in which MillerCoors is investing more money than ever before. “We’ve learned that we’ve got to go even further to connect with [21 to 34-year-old] consumers,” says Reis. -

Craft Brew: 50 Homebrew Recipes from the Worlds Best Craft Breweries Ebook

FREECRAFT BREW: 50 HOMEBREW RECIPES FROM THE WORLDS BEST CRAFT BREWERIES EBOOK Euan Ferguson | 192 pages | 01 Mar 2017 | Frances Lincoln Publishers Ltd | 9780711237339 | English | London, United Kingdom Craft Brew: 50 Homebrew Recipes from the World's Best Craft Breweries - Home- Brew Store Locations. Australia Post has advised they expect delivery delays during the Christmas period. For Christmas delivery order online before This book sees the most exciting, ground-breaking and pioneering craft breweries in the world reveal the recipes behind their best beers. Some 50 international craft breweries have volunteered a recipe from the mighty BrewDog to the much-loved Brooklyn in New York to create a unique, useful and technically accurate book for the homebrewer. This product is unable to be ordered online. Please check in-store availability. Enter your Postcode or Suburb to view availability and delivery times. Craft Brew offers a solid introduction to the kit required for all-grain brewing at home, including a glossary of the terms, and tips and techniques for getting the best brew at home. Contact 07 online qbd. The RRP set by overseas publishers may vary to those set by local publishers due to exchange rates and shipping costs. Due to our competitive pricing, we Craft Brew: 50 Homebrew Recipes from the Worlds Best Craft Breweries have not sold all products at their original RRP. Beer Recipes | Craft Beer & Brewing You are using an outdated browser not supported by The American Homebrewers Association. Please consider upgrading! Behind every great brewery are skilled craft brewers. These Craft Brew: 50 Homebrew Recipes from the Worlds Best Craft Breweries and women shed blood, sweat, and tears to bring their range of traditional and more experimental beers to our glasses. -

Salads Starters Handhelds Entrées Sides

MENU 11:00 am - 2:00 pm Lunch 5:00 pm – 10:00 pm Dinner 4:30 pm – 11:00 pm Bar *Drinks may be served until 2:00 a.m. DEVILED EGGS* MEATBALL SLIDERS* Spicy bacon, mustard or pickled beet Laced with melted mozzar ella cheese LOCAL (3 per serving). Mix and match or get and served on mini-brioche buns. 8.95 FAVORITES three of one kind. 5.50 PIEROGIES* Location pins on our LOCAL ARTISAN CHEESE Potato and Cheddar cheese topped menu make local BOARD with Turner’s Dairy sour cream, items easy to spot. A selection of three locally crafted chives and bacon. 6.50 Our local favorites cheeses from Emerald Valley Artisans served with fig jam, honey and bread LOADED PITTSBURGH FRIES* are found within a STARTERS Crisp thick-cut fries topped with beer 90-mile radius to our crisps. Your server has the details on today’s featured cheeses. 16.50 cheese, shredded short rib, grilled neighborhood. onions and bacon, topped with melted BEER CHEESE DIP LOCAL ARTISAN MEATS Gouda cheese. Served with Turner’s Served warm with onion BOARD* Dairy French onion dip. 9.25 focaccia pieces for dipping. 8.75 A selection of Thoma’s Meat Market sausage and meats served with THE CLW* whole-grain mustard and bread Roast turkey, corned beef, crisps. Your server has the details on short rib, bacon, slaw, today’s featured meats. 16.50 Russian dressing, Swiss cheese, mustard WINGS* and pickled onion. 15.25 Buffalo, mustard, lemon/garlic SHORT RIBS* or Pittsburgh. By increments of 6. -

GABF12 Winners List.Indd

2012 Brewery and Brewer of the Year Awards: Small Brewpub and Small Brewpub Brewer of the Year Sponsored by Briess Malt & Ingredients Co. Devils Backbone Brewing Company - Basecamp, Roseland, VA Devils Backbone Brewery Team Large Brewpub and Large Brewpub Brewer of the Year WINNERS LIST Sponsored by Brewers Supply Group The Church Brew Works, Pittsburgh, PA Steve Sloan oct 11-13, 2012 Brewpub Group and Brewpub Group Brewer of the Year Sponsored by Brewers Supply Group Great Dane Pub & Brewing Company, Madison, WI Category: 1 American-Style Wheat Beer, 29 Entries Rob LoBreglio Gold: Wagon Box Wheat, Black Tooth Brewing Co., Sheridan, WY Silver: Shredders Wheat, Barley Brown’s Brew Pub, Baker City, OR Small Brewing Company and Small Brewing Company Brewer of the Year Bronze: American Wheat, Gella’s Diner and Lb. Brewing Co., Hays, KS Sponsored by Microstar Keg Management Category: 2 American-Style Wheat Beer with Yeast, 29 Entries Funkwerks, Fort Collins, CO Gold: MBC Wheat Ale, Montana Brewing Co., Billings, MT Funkwerks Brewing Team Silver: Tumblewheat, Altitude Chophouse and Brewery, Laramie, WY Bronze: Wrangler Wheat, Figueroa Mountain Brewing Co., Buellton, CA Mid-Size Brewing Company and Mid-Size Brewing Company Brewer of the Year Category: 3 Fruit Beer, 58 Entries Sponsored by Brewers Supply Group Gold: Dry Dock Apricot Blonde, Dry Dock Brewing Co., Aurora, CO Troegs Brewing Company, Hershey, PA Silver: ChChChCh-Cherry Bomb, Thai Me Up Brewery, Jackson, WY John Trogner Bronze: Strawberry Blonde Ale, DESTIHL, Normal, IL Large Brewing -

Newsletter-September 2006

BURP NEWS The Official Newsletter of the BREWERS UNITED FOR REAL POTABLES 1981-2006 Silver Anniversary “I've figured out the real reason people are so warm in Munich. They are drunk." Cherie Sogsti, Travel Writer, on Oktoberfest Bill Ridgely, Editor 15 Harvard Court September 2006 (301) 762-6523; [email protected] Rockville, MD 20850 Marler Mash By Steve Marler, Fearless Leader Past is Prologue “The heritage of the past is the seed that brings forth the harvest of the future”. As we celebrate BURP’s September Meeting Anniversary, we see that the seeds planted 25 years ago have produced a harvest that is not only bountiful but BURP 25th Anniversary Crab Feast, also of excellent quality. Oktoberfest Celebration, & “War Between the States” Competition BURP had a handful of members when it started 25 At Seneca Creek State Park, MD years ago (less than 10), but now we have over 250 (Buck Pavilion) paying members. Many of our members, such as Bill Ridgely and Wendy Aaronson, put in a lot of time Saturday, Sep 23, 2006 and put on great events such as MASHOUT. A large 12:00-6:00 PM percentage of our membership continues to homebrew, and they bless us with large quantities of varied styles of October Meeting beer at meetings and other events. The quantity and 25th Anniversary Dark Beer Competition quality of brewing supplies and ingredients were not available when the club started, nor was the volume of Darnestown, MD literature we have today. I cannot speak from Sunday, October 22, 2006 experience but would have to surmise that the quality of 1:00-6:00 PM homebrew our members make today is much superior to 25 years ago. -

BURP News Is the Official Newsletter of Brewers United for Real Potables

SO LONG, AND THANKS FOR BURP ALL THE FISH WRAPPINGS NEWS The Official Newsletter of BREWERS UNITED FOR REAL POTABLES “So Many Brews So Little Time” Bruce Feist and Polly Goldman, Editors 926 Kemper Street E-Mail: [email protected] Alexandria, VA 22304-1502 [email protected] (703) 370-9509, Voice / (703) 370-9528/3171, BBS Febrewary 1997 What's Inside! What’s Brewing 1 Koch’s Koncepts 2 Upcoming Competitions 2 BURP Finances 2 Competition Notes 3 BURP Officers 3 Best of the Other Newsletters 4 Beer reviews in Pittsburgh 5 Beer reviews in New Mexico 6 New Members 6 Meeting Report 6 Letter to the Editor 7 Bike and Pub Crawl 7 Priming 7 Beer reviews in Tidewater 8 Campaign Statements 9 Blatant Filler 11 Directions to February Meeting 12 Designated Driver Program 12 Guide for New Members 12 BURP News is the official newsletter of Brewers United for Real Potables. BURP is dedicated to promoting homebrewing. Annual dues are $15 for individuals and $20 for couples. If you care about the beer you drink, join BURP. Please submit new memberships, changes of address, and corrections to BURP, 7430 Gene Street, Alexandria, VA 22315-3509. Articles for the BURP news should be delivered on diskette or paper to the Editor (address is in the masthead), uploaded to the Enlightened BBS at (703)370-9528, or e- mailed to Bruce Feist at [email protected]. Microsoft Word or text format is preferred. BURP News Febrewary 1997 Page 2 February 11, Elections / Meeting / Stout Competition 1997 at 6:00 PM at Oxon Hill February 14 Deadline for BURP Guide to DC Area Beer (see page 9) February 16 Deadline for March BURP News March 15 at 1:00 Meeting at Alison Skeel’s home in PM Kensington. -

2016 Annual Report

2016 ANNUAL REPORT Dear Friends, Our Audience Parents often tell me that each time they bring their child to the Children’s Museum, they learn something new about them. I can say firsthand that this is true — when let loose in the Art Studio or MAKESHOP, my children would demonstrate talents, knowledge or interests that I didn’t necessarily know they had. MUSEUM VISITORS Thank you for making this year one that I will always COMMUNITY-BASED remember. You, our loyal supporters, friends, volunteers, OUTREACH partners and staff, have inspired me more than words can 302,624 say. My hope for the coming years is that the Museum Highest admission 50,000 family continues to grow and we all continue to share in in our history! joy, creativity and curiosity together. students, teachers and families in schools and neighborhoods across the region Jennifer Broadhurst President, Board of Directors LOW-INCOME AND UNDERREPRESENTED AUDIENCES I feel a lot of love and gratitude for Jen as the final year Nearly NORTH AMERICAN of her board presidency comes to a close. She has been AUDIENCE a tremendous leader for the Children’s Museum, as 40,000 caring as she is smart and gracious, always willing to admissions* from: 3 million tell the Museum’s story and inspire support. people experienced a I believe one of the reasons Jen was a great board • Subsidized field trips Children’s Museum of president was because she saw her kids grow up at the • Four free admission days Pittsburgh exhibit at Museum. She first got involved with the Museum Board of Directors in 2004, when Jen and Brooks’ museums and libraries • $2 admission for children were as young as our youngest visitors. -

July and August Newsletter Frank B

June 30, 2014 July and August Newsletter Frank B. Fuhrer Wholesale Company Special points of interest: Belgian Independance Day Happy Birthday, America!!!!! Summer Selections The fourth of July is the birthday of our nation. Today, we celebrate and enjoy the freedom that comes with the event that made this day Limited Releases so special. The Declaration of Independence was not signed by all Website Information representatives until August, 1776. To make it official, John Hancock, President of the Continental Congress signed it. Now, can anyone Holiday Hours guess where the saying "put your John Hancock on it" came from!?! Today, we enjoy the benefits of the freedom which the framers signed and ultimately fought for. For us, it is a time for baseball, hot dogs, beer and family picnics. Summer is in full swing and life is good. Inside this issue: Seasonal Selections 6 Belgian Independence Day July 21st Fall Beers 10 Celebrate Belgian Independence day like a true Belgian….Belgium, beer is more than just a frothy Oktoberfest Beers 13 beverage - it is a culture. With over 450 different varieties, many Belgian beers have personalized beer glasses in which only that beer may be served. The shape of each glass enhances the flavor of the Pumpkin Beers 17 beer for which it is designed. This tradition may seem like behavior reserved for wine snobbery, but Belgians take their In memoriam 21 beer seriously - and with good reason. The country has enjoyed an unparalleled reputation for specialty beers since the Middle 22 Brewery News Ages. Connoisseurs favor Belgian beers for their variety, real flavor and character. -

Beer Styles Study Guide

Beer Styles Study Guide Today, there are hundreds of documented beer styles and a handful of organizations with their own unique classifications. As beer styles continue to evolve, understanding the sensory side of craft beer will help you more deeply appreciate and share your knowledge and enthusiasm for the beverage of beer. Take a deeper dive into America’s craft beer styles and improve your ability to describe the tastes, textures and aromas of beer. Here is your study guide that will help prepare you for what you might encounter when tasting craft beer. How to Use the Study Guide The CraftBeer.com Beer Styles Study Guide (below and available as a PDF) is for those who want to dive even deeper and includes quantitative style statistics not found in the Beer Styles section. Using an alphabetical list of triggers — from alcohol to yeast variety — this text will help describe possible characteristics of a specific beer style. The best part of learning about craft beer is getting to taste and experience what you’re studying. Use the CraftBeer.com Tasting Sheet to help you analyze and describe what you taste and if it’s appropriate for a particular beer style. The Beer Styles Study Guide may provide more information than many beer novices care to know. However, as your beer journey unfolds, your desire for more descriptors and resources will grow. Do All Craft Brewers Brew Beer to Style? Craft beer resides at the intersection of art and science. It is up to each individual brewer to decide whether they want to create beer within specific style guidelines or forge a new path and break the mold of traditional styles. -

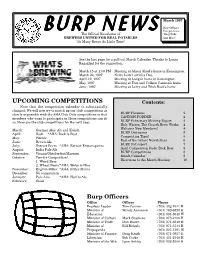

Newsletter-March 1997

March 1997 - New Officers BURPBURP NEWSNEWS - Competitions The Official Newsletter of - ‘Burg Pubs BREWERS UNITED FOR REAL POTABLES - And More! ”So Many Brews So Little Time” See the last page for a pull out March Calendar. Thanks to Lynne Ragazzini for the suggestion. March 15 at 1:00 PM Meeting at Alison Skeel’s home in Kensington. March 22, 1997 News Letter articles Due. April 19, 1997 Meeting at Langlie home in Kensington May, 1997 Meeting at Tom and Colleen Cannon’s home June, 1997 Meeting at Larry and Trish Koch’s home UPCOMING COMPETITIONS Contents: Note that the competition calendar is substantially changed: We will now try to match up our club competitions as closely as possible with the AHA Club Only competitions so that BURP Finances 2 members who want to participate in those competitions can do CANNON FODDER 2 so. Here are the club competitions for the next year. BURP Febrewary Meeting Report 3 Holy Waters; The Church Brew Works 4 March: German Ales: Alt and Kolsch Welcome New Members! 4 April: Bock *AHA: Bock is Best BURP Obituaries 5 May: Pilsner Competition Time! 5 June: Brown Ale Best of the (other) Newsletters 6 July: Extract Beers *AHA: Extract Extravaganza BURP Net report 7 August: India Pale Ale April Competition Style: Bock Beer 8 September: Vienna/Oktoberfest/Maerzen BURP Competitions 8 October: Two-fer Competition! March Calendar 9 1. Weird Beer Directions to the March Meeting 10 2. Wheat Beers *AHA: Weiss is Nice November: English Bitter *AHA: Bitter Mania December: No competition January: Pale Ales *AHA: Hail