The Future of Learning: How Technology Is Transforming Public Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 13 07 Page 1

TOLEDO SALES: 419-870-6565 Your Hispanic Weekly DETROIT, Since 1989. www. laprensa1.com FREE! TOLEDO: TINTA CON SABOR COLUMBUS CLEVELAND • LORAIN Ohio & Michigan’s Oldest & Largest Latino Weekly Check out our Classifieds! ¡Checa los Anuncios Clasificados! August/agosto 14, 2009 Spanglish Weekly/Semanal 16 Páginas Vol. 45, No. 23 DETROIT SALES: 313-729-4435 Judge Sonia Sotomayor Confirmed by Senate, page 2 Sonia Sotomayor 1st Hispanic Justice 3rd Woman to become Justice Lazo Cultural 111st Justice to the pp. 10-13 U.S. Supreme Court DENTRO: MI: State offices to close Friday, Aug 21 .............4 An Art is Born– Photography from Birth Bankruptcy…No Credit… By Ingrid Marie Rivera to 100 Years at Detroit Bad Credit…Divorce Institute of Arts ............4 La Prensa Correspondent Detroit Mayor Bing Ask about our With La Prensa advances to general ✔Guaranteed Commentary election ........................4 $19.5 Million for UM ... 4 Credit Approval American Cancer Gina Duran Jim Duran Society .........................5 Credit approval – go to Library News ...............5 citywidecreditapp.com Lucas County awarded Behavioral Health/ HOT BUY! Juvenile Justice Grant .5 City Club: The State of 05 Chevy Malibu Max 79k Real Estate ...................5 New Ohio BMV Service Available .....................5 Horoscopes ..................6 Obituaries ....................6 05 Chevy Cobalt black 44k 04 Mercury Mountaineer white 60k Communities celebrate Puerto Rican traditions AS LOW AS in Boricua Fest ...........7 $99 DOWN Requests for HHM DRIVES! Events ..........................7 Special Free Warranty! La Liga de Las 03 Mitsubishi Galant black 100k Americas .....................7 Deportes .......................7 CITY WIDE AUTO CREDIT Lazo Cultural ..... 10-13 Everyone Gets Approved! Classifieds ............ 14-15 1-866-477-4361 Se Habla Español! City Wide Happy Birthday 419-698-5259 Auto Credit Wheeling citywideautocredit.com Woodville Rd. -

Dear Teachers, You Are Our Heroes. Every Day of This Pandemic, You

Dear Teachers, You are our heroes. Every day of this pandemic, you have blown us away with your creativity, compassion, and commitment, your tenacity and heart. You have moved mountains to reach each child, wherever they are and despite the challenges that stand in your way. You’ve taught math classes while standing outside of homes, led online meditations to start the “school” day, created PE classes from your living room, filmed DIY science experiments, and found ways to check in with each kid. You’ve not only taught lessons; you have been our children’s lifeline to normalcy and stability, a tether and a point of connection. When Shonda Rhimes tweeted, "Been homeschooling a 6-year old and 8-year old for one hour and 11 minutes. Teachers deserve to make a billion dollars a year. Or a week," she put into words the collective appreciation of the nation’s parents. Here’s the secret you’ve known all along but is only now clear to the rest of us: It was always true. As leaders deeply invested in the nonpartisan, multi-sector, national effort to prepare and support 100,000 excellent preK-12 STEM teachers by 2021, we salute you. In our living rooms and kitchens, our bedrooms and makeshift one-room schoolhouses, we are standing and cheering for all the world to hear: “We love you, teachers!” Not because it’s easy or because you get it right every day. It isn’t, and you don’t. But you’ve chosen to get in the arena and stay there. -

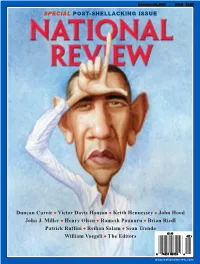

Special Post-Shellacking Issue

2010_11_29upc_cover61404-postal.qxd 11/9/2010 9:57 PM Page 1 November 29, 2010 49145 $3.95 SPECIAL POST-SHELLACKING ISSUE Duncan Currie w Victor Davis Hanson w Keith Hennessey w John Hood John J. Miller w Henry Olsen w Ramesh Ponnuru w Brian Riedl Patrick Ruffini w Reihan Salam w Sean Trende $3.95 William Voegeli w The Editors 48 0 74851 08155 6 www.nationalreview.com base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 11/8/2010 2:34 PM Page 1 HOW A STRATEGY TO HELP A IS PUTTING THOUSANDS OF REGIONAL STORE GO NATIONAL JOBS BACK ON THE MAP PROGRESS IS EVERYONE’S BUSINESS When a chain of retail stores needed capital to expand, we helped them find it. Soon, new stores were opening in other towns and other parts of the country. Providing value for families and job opportunities for thousands of inventory specialists, warehouse supervisors and managers in training. goldmansachs.com/progress ©Goldman Sachs, 2010. All rights reserved. Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black toc_QXP-1127940144.qxp 11/10/2010 1:25 PM Page 1 Contents NOVEMBER 29, 2010 | VOLUME LXII, NO. 22 | www.nationalreview.com ON THE COVER Page 12 From Defeat to Rout The weak economy and previous Democratic gains meant that Republicans Patrick Ruffini on the Tea Party would likely do well in this election, p. 22 especially in the House. But it was Democratic obstinacy that converted a BOOKS, ARTS defeat into a rout. The Editors & MANNERS COVER: ROMAN GENN 52 FOR GOD AND MAN ELECTION 2010 Conrad Black reviews The End and the Beginning: Pope John Paul 18 YES, THEY DID by John J. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E196 HON

E196 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks February 4, 2009 House in Indianapolis and throughout the ess clause of the Fifth Amendment, which trak. Amtrak is the main provider of all intercity state. concurrently prohibits the federal government passenger rail service in the United States Last year, Bill and his colleagues at The from depriving any person of life; and (4) Arti- and it is a key component of the American Times took the lead on establishing the One cle 1, Section 8, which gives Congress the economy. Region: One Vision concept with the goal of power to make laws necessary and proper to Amtrak is a safe, energy efficient transpor- uniting local leaders to advance all of North- enforce all powers in the Constitution. tation alternative that moves thousands of west Indiana as one community. In the past, The Supreme Court, in refusing to deter- people and tons of cargo every day. It also Northwest Indiana has been plagued by a lim- mine when human life begins and therefore employs thousands of Americans across the iting provincialism that has inhibited our area’s finding nothing to indicate that the unborn are country. What started as a proposal for a min- growth and potential. Under the One Region: persons protected by the Fourteenth Amend- imum of $5 billion in funding has already been One Vision concept, Bill and his colleagues ment, has left to Congress the responsibility of reduced to $1.1 billion in the base bill. Further have already brought local leaders together protecting the unprotected. The Court con- cuts are unacceptable; they would prevent the from across the area to start collaborating on ceded that, ‘‘If the suggestion of personhood development of intercity passenger rail in com- projects that will make Northwest Indiana a is established, the appellants’ case, of course, munities such as the Quad Cities in my home better place for everybody to live. -

SETDA's National Trends Report 2008

SETDA's National Trends Report 2008 http://www.setda.org A report from all 50 states plus DC regarding NCLB, Title II, Part D Enhancing Education through Technology (EETT) Study conducted by the Metiri Group STATE EDUCATIONAL TECHNOLOGY DIRECTORS ASSOCIATION February 2008 The State Educational Technology Directors Association (SETDA) was established in the fall of 2001 and is the principal association representing the state directors for educational technology. www.setda.org Metiri Group is a national consulting firm located in Los Angeles, California, which specializes in systems thinking, evaluation, and research related to educational technology. www.metiri.com Copies of the report on survey findings can be accessed in PDF format at www.setda.org. Message to the Reader The No Child Left Behind, Title II, Part D, Enhancing Education Through Technology (NCLB IID) program requires that participating State Education Agencies (SEAs) and Local Education Agencies (LEAs) focus their uses of technology on closing the achievement gap. While currently most states are implementing Round 6 (FY07) of the funding cycle, this report provides insights into the program implementation for Round 5 (FY06) and documents trend data across Rounds 1- 5. For the last five years, SETDA has commissioned the Metiri Group to work with the Data Collection Committee, to conduct a national survey to answer questions about the implementation of NCLB IID. The findings from SETDA¶s national survey provide states, local school districts, policymakers, and the U.S. with -

Construction News

November 9, 2012 Construction News AGC of Illinois—”Protectors of the Road Fund” 2012 AGCI Annual Convention—Speaker Spotlight 217-789-2650 The first seminar at the Annual Convention is the Labor Seminar at 10:00 a.m. on Mon- day, December 10th. We are proud to present three highly qualified labor attorneys to INSIDE THIS ISSUE discuss current issues between labor and management. Bereavement 2 Andy Martone of Hesse Martone, P.C. (Springfield & St. Louis) District Election Results 2 Andy is an Associate member and has made many presentations at the 2013 Midwinter Seminar 2 labor seminars during the Annual Convention in the past covering such News from the Executive 3 topics as pension withdrawal liability and Central States Pension Fund. Director The Labor Relations Institute repeatedly named Andy one of the Top 100 Upcoming Events 4 Labor Attorneys in America. The award is based on an objective evaluation of case results, and places Andy in the top 1% of all labor attorneys nation- wide. L. Steven Platt of Clark Hill P.C. (Chicago) Steve is an Associate member and has been practicing law since 1978 focusing his activities in labor and employment law as well as litigation. He Illinois State Operator has represented litigants in employment discrimination matters, did multi- 217-782-2000 employer Taft-Hartley fringe benefit fund work, ERISA and other general litigation. Steve holds the AV Peer Review Rating from Martindale- AGCI Staff Hubbell, its highest ratings for ethics and legal ability. He has been selected for inclu- Matt Davidson sion in Illinois Super Lawyers Magazine in the area of labor and employment law from Executive Director 2008 to the present. -

Support for Federal Acquisition of Thomson Correctional Center State Governor Pat Quinn (D-IL) Former Governor James R

Support for Federal Acquisition of Thomson Correctional Center State Governor Pat Quinn (D-IL) Former Governor James R. Thompson (R-IL) Former Governor Jim Edgar (R-IL) Illinois State Senator Mike Jacobs (D-36th District) Illinois State Representative Mike Boland (D-71st District) Illinois State Representative Jim Sacia (R-89th District) Illinois State Representative Pat Verschoore (D-72nd District) Illinois Association of Chiefs of Police Illinois Law Enforcement Alarm System Illinois Sheriff’s Associations Illinois State Police Illinois Department of Corrections Illinois Emergency Management Agency Illinois Office of Homeland Security Carroll County State’s Attorney Scott Brinkmeier Lee County State’s Attorney Henry S. Dixon Ogle County State’s Attorney John (Ben) Roe Stephenson County State’s Attorney John Vogt Whiteside County State’s Attorney Gary L. Spencer Federal Senator Dick Durbin (D-IL) Senator Roland Burris (D-IL) Senator Tom Harkin (D-IA) Representative Phil Hare (D-IL) Representative Jan Schakowsky (D-IL) Representative Bruce Braley (D-IA) Abner J. Mikva, Member of U.S. Congress (D-IL), 1969-1973, 1975-1979; White House Counsel, Clinton administration; Chief Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit, 1979-1994 Dan K. Webb, U.S. Attorney, Northern District of Illinois, 1981-1985 Thomas P. Sullivan, U.S. Attorney, Northern District of Illinois, 1977-1981; Former Co-Chair of the Illinois Governor's Commission on Capital Punishment, 2000-2008 Local Blackhawk Hills Resource Conservation and Development Boiler Makers Local -

AFSCME COUNCIL 31 ENDORSEMENTS 2010 GENERAL ELECTION Incumbents Are in Boldface Type

AFSCME COUNCIL 31 ENDORSEMENTS 2010 GENERAL ELECTION Incumbents are in boldface type. Voting records noted in parentheses. Statewide Offices US Senate Alexi Giannoulias D Governor/Lieutenant Governor Pat Quinn, Sheila Simon D Attorney General Lisa Madigan D Secretary of State Jesse White D Comptroller Judy Baar Topinka R Treasurer Robin Kelly D US House of Representatives 1st District Bobby Rush D (100%) 9th District Jan Schakowsky D (100%) 2nd District Jesse Jackson Jr. D (100%) 10th District Dan Seals D 3rd District Daniel Lipinski D (100%) 11th District Debbie Halvorson D (100%) 4th District Luis Gutierrez D (100%) 12th District Jerry Costello D (100%) 5th District Mike Quigley D (100%) 14th District Bill Foster D (89%) 7th District Danny Davis D (100%) 17th District Phil Hare D (100%) 8th District Melissa Bean D (89%) Illinois Senate 7th District Heather Steans D (73%) 43rd District AJ Wilhelmi D (63%) 10th District John Mulroe D 49th District Deanna Demuzio D (86%) 19th District Maggie Crotty D (63%) 51st District Tim Dudley D 22nd District Mike Noland D (77%) 52nd District Mike Frerichs D (88%) 28th District John Millner R (65%) 58th District Dave Luechtefeld R (65%) 40th District Toi Hutchinson D (77%) Illinois House of Representatives 7th District Karen Yarbrough D (70%) 72nd District Pat Verschoore D (85%) 11th District Ann Williams D 74th District Don Moffitt R (70%) 17th District Dan Biss D 85th District Maripat Oliver R 18th District Robyn Gabel D (Incomplete) 94th District Rich Myers R (75%) 26th District Will Burns D (70%) -

Fall 09 Vol37 No3:Winter 05 Vol33 No4.Qxd.Qxd

ITBE www.itbe.org Fall 2009 Vol.37 No.3 Newsletter Storytelling as a Bridge to Adult Language Learning by Cheri Pierson, Beata Lasmanowicz, Carolyn LaCosse, and Anitra Shaw Let us begin with examining what storytelling is. A story is a ‘We have told stories since the beginning of time. narrative account of real or imagined events that contains They are the narratives of life, spanning the centuries characters and a plot and can be long or short, extremely and connecting the generations. simple or highly complex (our definition). The telling of a They are the vessels in which we carry our shared story involves an oral presentation to an audience that is not adventures and most precious memories.’ merely the reading aloud or verbatim recitation of a story, Quote from Storytelling Foundation International, as cited at but re-creating an event and inviting listeners to involve ww.creativekeys.net/StorytellingPower/article1001.html themselves. Telling a good story requires several key com- ponents. First, know your listeners well and choose a story he adage “everyone loves a good story” seems to be that they can relate to and will find interesting. Second, tai- true across all cultures. As many English as a Second lor the complexity of your chosen story to the listeners’ level Language teachers know, a well chosen, effectively by varying the amount of details, difficulty of vocabulary, T use of idioms, overall length, and the grammatical structures delivered story quickly engages learners and draws them into a lesson. In addition to its natural appeal, storytelling and tenses that you use. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 111 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 111 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 156 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, JUNE 23, 2010 No. 95 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was Pursuant to clause 1, rule I, the Jour- For 93 years, Boys Town has helped called to order by the Speaker pro tem- nal stands approved. at-risk youth and families through a pore (Mr. PASTOR of Arizona). f variety of services, and the organiza- f tion has now expanded to 12 locations PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE nationally. Last year, the organization DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER The SPEAKER pro tempore. Will the served nearly 370,000 children and PRO TEMPORE gentleman from Vermont (Mr. WELCH) adults across the U.S., Canada and the The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- come forward and lead the House in the U.S. territories, as well as in several fore the House the following commu- Pledge of Allegiance. foreign countries. nication from the Speaker: Mr. WELCH led the Pledge of Alle- Boys Town has grown significantly WASHINGTON, DC, giance as follows: since Father Flanagan’s era. In 1977, June 23, 2010. I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the the Boys Town National Research Hos- I hereby appoint the Honorable ED PASTOR United States of America, and to the Repub- pital opened its doors and has become a to act as Speaker pro tempore on this day. lic for which it stands, one nation under God, national treatment center for children NANCY PELOSI, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. -

111Th Congress 1St Session RULES ADOPTED by THE

111th Congress ⎫ ⎬ COMMITTEE PRINT 1st Session ⎭ RULES ADOPTED BY THE COMMITTEES OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ——————— 111th Congress 2009-2010 ——————— COMPILED BY THE COMMITTEE ON RULES Printed for the use of the Committee on Rules 111th Congress ⎫ ⎬ COMMITTEE PRINT 1st Session ⎭ RULES ADOPTED BY THE COMMITTEES OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ——————— 111th Congress 2009-2010 ——————— COMPILED BY THE COMMITTEE ON RULES Printed for the use of the Committee on Rules ——————— U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 2009 COMMITTEE ON RULES LOUISE McINTOSH SLAUGHTER, New York, Chairwoman JAMES P. McGOVERN, Massachusetts, DAVID DREIER, California, Ranking Vice Chairman Member ALCEE L. HASTINGS, Florida LINCOLN DIAZ-BALART, Florida DORIS O. MATSUI, California PETE SESSIONS, Texas DENNIS A. CARDOZA, California VIRGINIA FOXX, North Carolina MICHAEL A. ARCURI, New York ED PERLMUTTER, Colorado CHELLIE PINGREE, Maine JARED POLIS, Colorado MUFTIAH MCCARTIN, Staff Director HUGH NATHANIAL HALPERN, Minority Staff Director ___________ SUBCOMMITTEE ON LEGISLATIVE AND BUDGET PROCESS ALCEE L. HASTINGS, Florida, Chairman DENNIS A. CARDOZA, California, Vice Chairman LINCOLN DIAZ-BALART, Florida, CHELLIE PINGREE, Maine Ranking Member JARED POLIS, Colorado DAVID DREIER, California LOUISE McINTOSH SLAUGHTER, New York ___________ SUBCOMMITTEE ON RULES AND ORGANIZATION OF THE HOUSE JAMES P. McGOVERN, Massachusetts, Chairman DORIS O. MATSUI, California, Vice Chairman PETE SESSIONS, Texas, Ranking MICHAEL A. ARCURI, New York Member ED PERLMUTTER, Colorado VIRGINIA FOXX, North Carolina LOUISE McINTOSH SLAUGHTER, New York (II) C O N T E N T S ————— PART I.–STANDING COMMITTEES OF THE HOUSE Page Committee on Agriculture…......……………………………………………………………………………..3 Committee on Appropriations………………………………………………………………………………29 Committee on Armed Services……………………………………………………………………………...43 Committee on the Budget……………………………………………………………………………………57 Committee on Education and Labor……………………………………………………………………….67 Committee on Energy and Commerce……………………………………………………………………. -

Government Relations Update Election 2010 Special Edition

Government Relations Update Election 2010 Special Edition The Political Pendulum Swings Back to Favor GOP period of Democratic dominance, but only two years later the public has voted for change. While some are sure to trumpet the Republican victory as a validation of the GOP’s agenda, recent history warns of over- interpreting the election results. Analysts and pundits have repeatedly argued over the last several election cycles that a significant victory by one party or the other is the first step to an enduring or permanent majority; however, after last night’s results, it is clearer than ever that the pendulum continues to swing, and that the U.S. political waters continue to be roiled. While Republicans and Democrats both may overstate the long-term significance of last night’s Republican victory, there are some broad mes- sages from yesterday’s results. First and foremost, voters across the board are deeply concerned that the economy has not rebounded. Voters force- fully rejected the assertion by economists and the Obama administration that the economy is in recovery. Second, there is great unease about the John Boehner (R – Ohio) policies being pursued to address the economic crisis. The various policy For the third time in four years, Americans battles of the last two years—stimulus, health care reform, and financial have voted for major change in Washington. Last services reform—were grouped together by voters and viewed as an night was a resounding victory for the GOP as ineffective, contentious, and confusing agenda. they took control of the House of Representatives Last night’s results have delivered a House of Representatives in which with historic gains, significantly improved their the caucuses of both parties have been pulled further away from the center.