The Music of Ghulam Haider

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

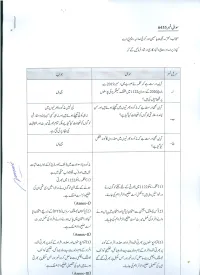

Schedule for Written Test for the Posts of Lecturers in Various Disciplines

SCHEDULE FOR WRITTEN TEST FOR THE POSTS OF LECTURERS IN VARIOUS DISCIPLINES Please be informed that written test for the posts of Lecturers in the following departments / disciplines shall be conducted by the University of Sargodha as per schedule mentioned below: Post Applied for: Date & Time Venue 16.09.2018 Department of Business LECTURER IN LAW (Sunday) Administration, (MAIN CAMPUS) University of Sargodha, 09:30 am Sargodha. Roll # Name & Father’s Name 1. Mr. Ahmed Waqas S/o Abdul Sattar 2. Ms. Mahwish Mubeen D/o Mumtaz Khan 3. Malik Sakhi Sultan Awan S/o Malik Abdul Qayum Awan 4. Ms. Sadia Perveen D/o Manzoor Hussain 5. Mr. Hassan Nawaz Maken S/o Muhammad Nawaz Maken 6. Mr. Dilshad Ahmed S/o Abdul Razzaq 7. Mr. Muhammad Kamal Shah S/o Mufariq Shah 8. Mr. Imtiaz Ali S/o Sahib Dino Soomro 9. Mr. Shakeel Ahmad S/o Qazi Rafiq Ahmad 10. Ms. Hina Sahar D/o Muhammad Ashraf 11. Ms. Tahira Yasmeen D/o Sheikh Nazar Hussain 12. Mr. Muhammad Kamran Akbar S/o Mureed Hashim Khan 13. Mr. M. Ahsan Iqbal Hashmi S/o Makhdoom Iqbal Hussain Hashmi 14. Mr. Muhammad Faiq Butt S/o Nazzam Din Butt 15. Mr. Muhammad Saleem S/o Ghulam Yasin 16. Ms. Saira Afzal D/o Muhammad Afzal 17. Ms. Rubia Riaz D/o Riaz Ahmad 18. Mr. Muhammad Sarfraz S/o Ijaz Ahmed 19. Mr. Muhammad Ali Khan S/o Farzand Ali Khan 20. Mr. Safdar Hayat S/o Muhammad Hayat 21. Ms. Mehwish Waqas Rana D/o Muhammad Waqas 22. -

Final List MBBS.Xlsx

Final Selection Merit List of MBBS 2020-21 Application Merit Merit S.No Applicant Name Father/Guardian/Name Gender Number Standing Score 1 30524 2256 Vaneeza Khan Bhand Rehmatullah Bhand 62.218 F 2 31242 2289 Salwa Muhammad Saleem 62.15 F 3 22118 2384 Aisha Jatoi Muhammad Baqir Yousif 61.941 F 4 22645 2413 Warisha Waseem Waseem Ahmed Chohan 61.841 F 5 26993 2449 Irfan Khan Ali Khan Shar 61.736 M 6 20539 2453 Ramsha Shams Shams Ul Haque 61.736 F 7 12657 2507 Aqsa Zareen Abdul Hafeez Memon 61.595 F 8 32822 2554 Sandhya Parshotam 61.477 F 9 22949 2590 Iqra Abdul Waheed 61.364 F 10 24731 2594 Priyanka Devi Durga Das 61.355 F 11 26844 2597 Eman Asif Muhammad Asif 61.345 F 12 28577 2620 Dhan Raj Kumar Reva Chand 61.291 M 13 32385 2640 Ritu Tikam Das 61.223 F 14 25690 Add.List Hadiqa Khurram 61.18 F 15 32968 2697 Kainat Mustafa Ghulam Mustafa 61.041 F 16 21240 2704 Manoj Kumar Kishwar Das 61.018 M 17 19031 2760 Saifullah Khalid Hussain 60.873 M 18 24566 2796 Rizwan Ahmed Ghulam Zakir 60.791 M 19 20213 2844 Kashaf Naz Ghafoor Bux 60.686 F 20 18302 2846 Mehak Lal Dino 60.682 F 21 29855 2895 Rafidah Iqra Mohammad Jamshed Akhtar 60.573 F 22 22744 2961 Habibullah Muhammad Ali 60.432 M 23 12710 2982 Jawad Ali Akhtiar Ali 60.386 M 24 19252 3038 Laraib Noor Shaheed Dr Wilayat Ali Gopang 60.259 F 25 17996 3115 Shabeeh Ul Hassan Aijaz Ahmed 60.114 M 26 12734 3156 Yogeeta Jagdesh Kumar 60.036 F 27 26059 3165 Moatar Nisar Nisar Ahmed 60.009 F 28 16273 3172 Ali Fatima Khalid Hussain Hakro 59.991 F 29 19760 3175 Juhi Maheshwari Ashok Kumar 59.982 F 30 16080 -

Women Performing Artists in Colonial India There Were Few Women Painters in Colonial India

I. (A) Personal Details Role Name Affiliation Principal Investigator Prof. Sumita University of Allhabad Parmar Paper Coordinator Prof Rekha Pande University of Hyderabad Author Dr. Archana Verma Independent Scholar Content Reviewer (CR) Prof Rekha Pande University of Hyderabad Language Editor (LE) Prof. Sumita University of Allhabad Parmar (B) Description of Module Items Description of Module Subject Name Women’s Studies Paper Name Women and History Module Name/ Title, Women performers in colonial India description Module ID Paper- 3, Module-30 Pre-requisites None Objectives To explore the achievements of women performers in colonial period Keywords Indian art, women in performance, cinema and women, India cinema, Hindi cinema Women Performing Artists in Colonial India There were few women painters in Colonial India. But in the performing arts, especially acting, women artists were found in large numbers in this period. At first they acted on the stage in theatre groups. Later, with the coming of cinema, they began to act for the screen. Cinema gave them a channel for expressing their acting talent as no other medium had before. Apart from acting, some of them even began to direct films at this early stage in the history of Indian cinema. Thus, acting and film direction was not an exclusive arena of men where women were mostly subjects. It was an arena where women became the creators of this art form and they commanded a lot of fame, glory and money in this field. In this module, we will study about some of these women. Nati Binodini (1862-1941) Fig. 1 – Nati Binodini (get copyright for use – (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Binodini_dasi.jpg) Nati Binodini was a Calcutta based renowned actress, who began to act at the age of 12. -

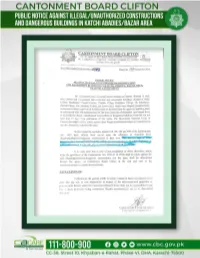

Public Notice Against Illegal / Unauthorized Constructions

CANTONMENT BOARD CLIFTON CC-38, Street 10, Kh-e-Rahat, Phase-VI, DHA, Karachi-75500 Ph. # 35847831-2, 35348774-5, 35850403, 35348784, Fax 5847835 Website: www.cbc.gov.pk _____________________________________ No. CBC/Lands/Publication/012/ Dated the 16 December 2020. PUBLIC NOTICE AGAINST ILLEGAL/UNAUTHORIZED CONSTRUCTION AND DANGEROUS BUILDINGS IN KATCHI ABADIES/BAZAR AREA CLIFTON CANTONMENT All concerned/owners/occupants/lessees/tenants are hereby directed in their own interest and convenience that residential and commercial buildings situated at Delhi Colony, Madniabad, Punjab Colony, Chandio Village, Bukhshan Village, Ch. Khaliq-uz-Zaman Colony, Pak Jamhoria Colony and Lower Gizri, which were illegally/unauthorizedly constructed without approval of building plans or deviated from the approved building plans or constructed with sub- standard material and may cause loss of properties and human lives, to demolish the illegal, unauthorized constructions or dangerous buildings forthwith but not later than 15 days from publication of this notice. The Honourable Supreme Court of Pakistan has taken serious notice against these illegal/unauthorized/dangerous constructions and also directed to demolish the same. In this regard the requisites notices U/S 126, 185 and 256 of the Cantonments Act, 1924 have already been served upon the offenders to demolish these illegal/unauthorized/dangerous constructions at their own. The details of such properties are as under:- DEHLI COLONY NO.01 S. Property Name of present owner Violation/ status of Name of original Lessee No. No. as per record of CBC illegal construction 1 A-01/01 Mr. Noor Bat Khan Mrs. Abida Noor Ground + 7th Floor 2 A-01/02 Mr. -

Stamps of India - Commemorative by Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890

E-Book - 26. Checklist - Stamps of India - Commemorative By Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890 For HOBBY PROMOTION E-BOOKS SERIES - 26. FREE DISTRIBUTION ONLY DO NOT ALTER ANY DATA ISBN - 1st Edition Year - 1st May 2020 [email protected] Prem Pues Kumar 9029057890 Page 1 of 76 Nos. YEAR PRICE NAME Mint FDC B. 1 2 3 1947 1 21-Nov-47 31/2a National Flag 2 15-Dec-47 11/2a Ashoka Lion Capital 3 15-Dec-47 12a Aircraft 1948 4 29-May-48 12a Air India International 5 15-Aug-48 11/2a Mahatma Gandhi 6 15-Aug-48 31/2a Mahatma Gandhi 7 15-Aug-48 12a Mahatma Gandhi 8 15-Aug-48 10r Mahatma Gandhi 1949 9 10-Oct-49 9 Pies 75th Anni. of Universal Postal Union 10 10-Oct-49 2a -do- 11 10-Oct-49 31/2a -do- 12 10-Oct-49 12a -do- 1950 13 26-Jan-50 2a Inauguration of Republic of India- Rejoicing crowds 14 26-Jan-50 31/2a Quill, Ink-well & Verse 15 26-Jan-50 4a Corn and plough 16 26-Jan-50 12a Charkha and cloth 1951 17 13-Jan-51 2a Geological Survey of India 18 04-Mar-51 2a First Asian Games 19 04-Mar-51 12a -do- 1952 20 01-Oct-52 9 Pies Saints and poets - Kabir 21 01-Oct-52 1a Saints and poets - Tulsidas 22 01-Oct-52 2a Saints and poets - MiraBai 23 01-Oct-52 4a Saints and poets - Surdas 24 01-Oct-52 41/2a Saints and poets - Mirza Galib 25 01-Oct-52 12a Saints and poets - Rabindranath Tagore 1953 26 16-Apr-53 2a Railway Centenary 27 02-Oct-53 2a Conquest of Everest 28 02-Oct-53 14a -do- 29 01-Nov-53 2a Telegraph Centenary 30 01-Nov-53 12a -do- 1954 31 01-Oct-54 1a Stamp Centenary - Runner, Camel and Bullock Cart 32 01-Oct-54 2a Stamp Centenary -

Music/Singers

DESIZN CIRCLE , DELHI I NOIDA WWW.DESIZNCIRCLE.COM Music/Singers There are two major styles of classical music unique to India- 1. The Hindustani style popular in North India and 2. The Carnatic style popular in South India. BhaKti/devotion to God is the main purpose of classical music and hence the theme and content of the songs sung/played are heavily religious or spiritual. The songs/kritis/kirtans are set to melodious tunes called ‘ragas’ and time beats/rhythms called taal/taalas’. • Great poets and holy men liKe Tulsidas, Surdas, Meera Bhai, Namdev, Ek Nath, Kabir have contributed the lyrics of the songs in the Hindustani style. • Thyagaraja, Muthuswamy Dikshitar, and Shyma Sastrigal are considered the big three among composers (lyrics and music) in the carnatic style. • Some of the other composers are Purandara dasa, Annamacharya, Narayana Tirthar and Swati Thirunal. • In the Hindustani style, Pandit Bhimsen Joshi, Pt. Jasraj, Rajan Mishra and Sajan Mishra, Kishori Amolkar, Prabha Apte, Girija devi, Parveen Sultana, Shubha Mudgal are some of the vocalists famous for their vocal recitals both within our country and abroad. • In the Carnatic Style, Dr. Bal Murali Krishna Madurai Shesha Gopalan are two of the many veterans who inspire the youth to learn classical music and Keep the tradition alive. • Late M. S Subbulakshmi’s voice had the power to mesmerize any number of listeners during her recitals. • Vocalists who are now popular are Sudha Raghunathan, Aruna Sairam, Sowmya, Nithyasree Mahadevan, Unnikrishnan, T.N. Krishna. Hyderabad bothers, Sanjay Subramanian, Neyveli Santanam Hyderabad bothers, Jesudas. • Here is a list of exponents of some of the Indian musical instruments. -

BFA Entry Test Passed Candidates Result 2015-16 (Graphic Design, Textile Design, Painting)

University College of Art & Design University of the Punjab BFA Entry Test Passed Candidates Result 2015-16 (Graphic Design, Textile Design, Painting) Note: For Further information regarding the admission procedure, Kindly consult the newspaper to be published on 30th August 2015. (The University reserves the right to correct any typographical error, omission etc.) Roll # Name Father / Guardian's Name 3 Fawad Majeed Abdul Majeed 4 Isra Zia Muhammad Zil Ullah Rana 5 Amal Arif Muhammad Arif 6 Rabia Yaseen Haifz Ghulam Yaseen 7 Hamna Masood Masood Hussain Siddiqui 8 Hira Sultan Babar Sultan 10 Mahnoor Zahra Rizvi Syed Farhat Hussain 11 Aqas Amjad Amjad Ali 14 Anam Zia Mohammad Zia ul Haq 16 Haiqa Chaudhry Humayun Rasheed 17 Fatima Usman Muhammad Usman 19 Akash Faheem Muhammad Faheem 20 Muhammad Waqar Muhammad Farooq 21 Saman Imran Mumtaz Imran 24 Syed Badar Syed Altaf Hussain 25 Muhammad Rameez Saleem Muhammad Saleem 26 Sohail Afzal Muhammad Afzal 27 Fizza Raghib Raghib Ali Prepared by Admin. Officer Convener Admission Committee Principal University College of Art & Design University of the Punjab BFA Entry Test Passed Candidates Result 2015-16 (Graphic Design, Textile Design, Painting) Note: For Further information regarding the admission procedure, Kindly consult the newspaper to be published on 30th August 2015. (The University reserves the right to correct any typographical error, omission etc.) Roll # Name Father / Guardian's Name 28 Hira Amir Sarfraz Amir Sarfraz 30 Zunaira Wahab Abdul Wahab 32 Iqra Riaz Muhammad Riaz 33 Kiran Ashraf Muhammad Ashraf 34 Rimsha Rizvi Shakil ur Rahman Rizvi 35 Muhammad Yasir Altaf Hussain 36 Imran Shahid Shahid Maqbool Naz 37 Fizza Hassan Hassan Raza 38 Remsha Anwar Muhammad Anwar 39 Asia Fayyaz Fayyaz Ahmed 40 Murrad Rahim Khan Izhar Rahim Khan 41 Hooria Alam Shah Alam Zaidi 42 Zamiah Mehmood Mehmood Ahmad Khan 43 Duaa Nauman Nauman Nasir 45 Aneeka Farooqi Abdul Hannan Farooqi 46 Ameera Hasan Khan Ahmed Hassan Khan 47 Firza Razi Dar Razi ud Din Dar 48 Farhan Tufail Muhammad Tufail Prepared by Admin. -

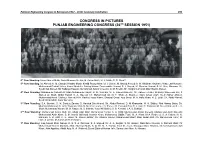

36Th Session 1951)

Pakistan Engineering Congress in Retrospect (1912 – 2012) Centenary Celebration 659 CONGRESS IN PICTURES PUNJAB ENGINEERING CONGRESS (36TH SESSION 1951) 6th Row Standing: Nisar Ahmed Malik; Abdul Mannan Sheikh; M. Aslam Mufti; M. A. Malik; R. R. Shariff 5th Row Standing: M. Ahmed; N. M. Chaudri; Mazhar Munir; Khalid Faruq Akbar; M. I. Chishti; M. Masud Ahmed; A. W. Khokhar; Mazhar-ul-Haq; Latif Hussain; Muhammad Rashid Vehra; Kamal Mustafa; Ashfaq Hasan; Ferozeuddin Ahmad; S. I. Ahmed; M. Shamim Ahmed; S. M. Niaz; Monawar Ali; Syed Irfan Ahmed; Mir Sadaqat Hassan; Muhammad Ashraf Cheema; G. M. Sheikh; Kh. Maqbool Ahmad; Mian Bashir Ahmed. 4th Row Standing: Muhammad Saadat Ali; Mian Muhammad Hayat; G. M. Subhani; M. A. Hamid Rahmani; Sh. Zahoor ul Haq; Khawaja Saleemud Din; S Ahmed Ali Shah; Abdul Hamid; S. A. Majeed; Ch. Muhammad Ali; M. T. Shah; A. Khalique; Malik Aman Ullah; Syed Iftikhar Ahmed; Muhammad Hanif; Shafique Ahmed; M A. Rashid; Fazal Karim; Shaukat Omar; Aziz Omar; M. A. Hafiz Khan; H. S. Zaidi; Ch. Abdul Hamid; Syed Mahdi Shah; Asrar Qureshy. 3rd Row Standing: S.A. Qureshi; S. M. Serajuz Zaman; S. Hamiud Din Ahmed; Sh. Abdur Rawoof; D. M Khanzada; M. H. Siddiqi; Rab Nawaz Batra; Sh. Mukhtar Mahmood; S. Jaffar Hussain; Malik N. M. Khan; Jameel A. Parvez; M. Faizanul Haq; H. J. Asar; F. Rahman: M. Saeed Ahmed; S. I. A. Shah; Muhammad Akram; M. M. Haque; M. S. Minhas; Yusuf Ali Siddiqi; S. S. Kirmani; I. A. S. Bokhari. 2nd Row Standing: Muhammad Aslam Butt; Ch. Abdul Azjz; Mian Muhammad Yunas; S. -

THE RECORD NEWS ======The Journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’, Mumbai ------ISSN 0971-7942 Volume - Annual: TRN 2007 ------S.I.R.C

THE RECORD NEWS ============================================================= The journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’, Mumbai ------------------------------------------------------------------------ ISSN 0971-7942 Volume - Annual: TRN 2007 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ S.I.R.C. Branches: Mumbai, Pune, Solapur, Nanded, Tuljapur, Baroda, Amravati ============================================================= Feature Article in this Issue: Gramophone Celebrities-II Other articles : Teheran Records, O. P. Nayyar. 1 ‘The Record News’ – Annual magazine of ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ [SIRC] {Established: 1990} -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- President Narayan Mulani Hon. Secretary Suresh Chandvankar Hon. Treasurer Krishnaraj Merchant ==================================================== Patron Member: Mr. Michael S. Kinnear, Australia -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Honorary Members --------------------------- V. A. K. Ranga Rao, Chennai Harmandir Singh Hamraz, Kanpur -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Membership Fee: [Inclusive of journal subscription] Annual Membership Rs. 1,000 Overseas US $ 100 Life Membership Rs. 10,000 Overseas US$ 1,000 Annual term: July to June Members joining anytime during the year [July-June] pay the full membership fee and get a copy -

Roshan Ara Begum

Roshan Ara Begum Performing Classical Music, Gender, and Muslim Nationalism in Pakistan Fawzia Afzal-Khan The performance — or lack thereof — of (North Indian) classical music in Pakistan, and espe- cially the obstacles women performers have faced, cannot only be blamed on Islam’s putative hostility to the musical and performing arts in general and to women performing in public in particular. Rather, the discourse of a religiously inflected nationalism collides with gendered, classed bodies within the performative space of a political imaginary such that the role played by music both constitutes and deconstructs this history. Women singers’ roles are crucial in Fawzia Afzal-Khan is University Distinguished Scholar/Professor of English at Montclair State University and Visiting Professor at NYU Abu Dhabi. She is the author of Cultural Imperialism: Genre and Ideology in the Indo-English Novel (Penn State Press, 1993), A Critical Stage: The Role of Secular Alternative Theatre in Pakistan(Seagull Press, 2005), and Lahore with Love: Growing Up with Girlfriends Pakistani Style (Syracuse University Press, 2010); and editor of The PreOccupation of Postcolonial Studies (Duke University Press, 2000) and Shattering the Stereotypes: Muslim Women Speak Out (Interlink Books, 2005). Siren Song: Pakistani Women Singers is her award-winning NEH- funded short film and forthcoming book from Oxford University Press. She is an Indian classical singer, a playwright, and a poet. [email protected] TDR: The Drama Review 62:4 (T240) Winter 2018. ©2018 8 Fawzia Afzal-Khan Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/dram_a_00790 by guest on 02 October 2021 both shaping and resisting this politically performative historical space of the Pakistani nation, yet are hardly well understood or appreciated. -

6455.Pdf, PDF, 1.27MB

Overall List Along With Domicile and Post Name Father Name District Post Shahab Khan Siraj Khan PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Sana Ullah Muhammad Younas Lower Dir 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Mahboob Ali Fazal Rahim Swat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Tahir Saeed Saeed Ur Rehman Kohat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Owais Qarni Raham Dil Lakki Marwat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Ashfaq Ahmad Zarif Khan Charsadda 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Saud Khan Haji Minak Khan Khyber 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Qamar Jan Syed Marjan Kurram 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Kamil Khan Wakeel Khan PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Waheed Gul Muhammad Qasim Lakki Marwat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Tanveer Ahmad Mukhtiar Ahmad Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muhammad Faheem Muhammad Aslam PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muslima Bibi Jan Gul Dera Ismail Khan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muhammad Zahid Muhammad Saraf Batagram 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Riaz Khan Muhammad Anwar Lower Dir 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Bakht Taj Abdul Khaliq Shangla 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Hidayat Ullah Fazal Ullah Swabi 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Wajid Ali Malang Jan Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Sahar Rashed Abdur Rasheed Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Afsar Khan Afridi Ghulam Nabi PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Adnan Khan Manazir Khan Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Liaqat Ali Malik Aman Charsadda 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Adnan Iqbal Parvaiz Khan Mardan 01. -

Anil Biswas – Filmography Source: Hamraz’S Hindi Film Geet Kosh (Digitization: Ketan Dholakia, Vinayak Gore, and Balaji Murthy)

Anil Biswas – Filmography Source: Hamraz’s Hindi Film Geet Kosh (Digitization: Ketan Dholakia, Vinayak Gore, and Balaji Murthy) Contents Anil Biswas – Filmography ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1) Dharam Ki Devi ..................................................................................................................... 3 2) Fida-e-Vatan (alias Tasveer-e-vafa) ...................................................................................... 3 3) Piya Ki Jogan (alias Purchased Bride) ................................................................................... 3 4) Pratima (alias Prem Murti) ..................................................................................................... 4 5) Prem Bandhan (alias Victims of Love) .................................................................................. 4 6) Sangdil Samaj ......................................................................................................................... 4 7) Sher Ka Panja ......................................................................................................................... 5 8) Shokh Dilruba ......................................................................................................................... 5 9) Bulldog ................................................................................................................................... 5 10) Dukhiari (alias A Tale of Selfless Love)