Federalism and Foreign Direct Investment: How Political Affiliation Determines the Spatial Distribution of FDI – Evidence from India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Red Alert for 5 Telangana Districts, Yellow For

Follow us on: @TheDailyPioneer facebook.com/dailypioneer RNI No. TELENG/2018/76469 Established 1864 ANALYSIS 7 MONEY 8 SPORTS 12 Published From FUELS UNDER GST: A PROPER HYDERABAD DELHI LUCKNOW BENCHMARKS CLIMB TO NEW LIFETIME BHOPAL RAIPUR CHANDIGARH ILLOGICAL PROPOSITION HIGHS; RIL, IT STOCKS LEAD CHARGE TEST WIN BHUBANESWAR RANCHI DEHRADUN VIJAYAWADA *LATE CITY VOL. 3 ISSUE 318 HYDERABAD, TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 7, 2021; PAGES 12 `3 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable NABHA TO BE MAHESH AND TRIVIKRAM'S SECOND LEAD? { Page 11 } www.dailypioneer.com VHP: RAM TEMPLE FOUNDATION TO BE SC REFUSES TO DEFER NEET-UG CHHATTISGARH GOVERNMENT WAIVES PARTY THAT GETS 120-130 LS SEATS READY BY OCT, ‘GARBHAGRIHA' BY ’23 EXAM SCHEDULED ON SEPTEMBER 12 OUTSTANDING LOAN OF WOMEN SHGS WILL LEAD OPPN FRONT: KHURSHID he foundation of the Rama temple in Ayodhya will be he Supreme Court Monday refused to defer the hhattisgarh Chief Minister Bhupesh Baghel on Monday he Congress is still in the "best position" to clinch 120- completed by the end of September or the first week of National Eligibility-cum-Entrance Test-UG examination, announced waiving off the overdue or unpaid loans 130 seats in the next Lok Sabha elections and assume TOctober and Ram Lalla will be consecrated in the Tscheduled for September 12, saying it does not want to Cworth Rs 12.77 crore of the women SHGs so that they Tthe leadership role in a prospective anti-BJP opposition ‘garbhagriha' (sanctum sanctorum) by December 2023 interfere with the process and it will be "very unfair" to can avail fresh loans to start new economic activities. -

Epdffile5e1c5329ecfda5.34903735

������������������������ ��������� ����� ��� ���� ��������� ������� ������ �� ��� ����� ����� ����� ����� �� ��� ��� �� ������� ���� ����� ������� �� ��� ���"����� �� ��� ��� ����� �� ��� ���� �������� �� ����� � !"## ����� ��$ !�#" ���� ���� �� ��� ������� ����� ����������� ��!�� ���"������ ���� ���� ��������� ����� %�&�� �� ��� ��� ������ ���� ���������� ��� ������ �� ��'������ � ��� �!�� ����"������ ������ ������ ������ ��&����(����) *�� *�� �� ����#������������ ��� �������� ��� ������ � ������ +�,�� ����������# ������������# ��� ������� ���� ���-�. ��� ����� ����� "���������#;(���"����"����� ��� ���� �/���$ ���0��� ��'��% &������� ����� ����$ ������ ��$ ��� ����� �����<������#!���������� ������� ���� ������� �� ��� ����� ����� �� ����� �/�����$��% �� ��� ���������������$%���������� ��� ������ ����� �� ��'������ �� �&�� !122 �� ������� ���� �� �""���������� ������������������������ ��� ��� �� ������ �������� "����� �����<���#�� ����$ ��� ���������� �� ��� ������ &��� ����� �� ��� �� �� � %�� ���� "������� �� ����� ��� ������� ��������� �� ���� �!�#�������������������� �� �=22 ����� ��� �12= ����� ���� �� ���������� ���� �� ��� ����� ��������# ��� �� ��!�� �� ��� ���"����� �� ������� ���������� ���� ����� ���� �� ����"������ �������� ��!���������#��� ��� �� ��� ���� �� ����� ������ ����� �������� �� ������ ����� �������� � ���� � �� �� ��� ����� �� ���� ����$ ������ �� &����� *���� "���� ����������������� �!���� ��!����!��� !������� �� ��� ����! �� "��" ���� %�� ������� ���� ��� ����� ��� �������� ���� ���� ������� ��� ����� �� ��� -

REMEMBRANCE Progress," He Said

SUNDAY, JULY 29, 2018 (PAGE 4) DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU From page 1 MISCELLANEOUS PLACEMENT CORRECTION OF NAME Admn initiates proceedings under Code of Omar calls for Oppn unity I No. 4478448Y Hav. Harpreet Singh REQUIRED son of Harchand Singh R/o Kakrali, Required Marketing Executive Minister,” he said. able federal front. Criminal Procedure against 2 contractors Teh & Distt. Ropar, C/o 56APO declare on Distributor Pay Roll in Jammu “Obviously no effort for The National Conference that the name of my son Jashanpreet sive public outcry in the local which includes imprisonment up to for International Brand area and people fear failure of six months and fine or with both. towards opposition unity will vice-president, who called on Singh is wrongly written as Jaspreet really succeed unless the Banerjee at the State Secretariat Singh in official Army record. Applied Min. Qualification:- Matric the projects on account of cost The proceedings under for correction of same. Objection if escalations", read the conditional Section 133 CrPC have also Congress is able to take the fight here yesterday, said he was look- Candidate must have bike to the BJP in the way we hope,” ing forward to working closely any convey to concerned authority order of the District Magistrate. been initiated against another within seven days. Contact: 9906015699 Stating that delay caused by private contractor namely Joy Abdullah said on the sidelines of with her and other like-minded the contractor on important roads Kokhar, a resident of Christian a programme here. leaders in the next Lok Sabha The former Jammu and elections. -

Change Is on Its Way January 5, 2014 S

Established 1946 Price : Rupees Five Vol. 68 No. 52 Change is on its way January 5, 2014 S. Viswam The first task for all of us here already formed a government in in Janata, a pleasant one, is to wish Profligate legislators Delhi. It has announced that it intends all our readers a happy 2014. In the Kuldip Nayar to go national and field a substantial context of national politics, the year number of candidates for Parliament. we have just ushered in is a crucial The party is not lacking in public Apartheid of the world unite! one for the polity and the country. support for its unconventional style K. S. Chalam We begin 2014, as we have done of politics. The people at large are with earlier new year arrivals, with funding it in a surprisingly big way. hope laced with abundant optimism. Its anti-corruption crusade, initially No roadblocks for AAP agenda The year we have just rung out did launched under Hazare’s inspiration Nitish Chakravarty not meet with all our expectations. and leadership, has caught popular Indeed, it left us highly dissatisfied, imagination, which has been further displeased and even angry. But it has fortified by the welfare measures set gone. Let it go. Why I am not in AAP? in by the Kejriwal government. In Sandeep Pandey short, the ground has been laid, and But in its own way, it gave some now exists, in many states of India, for shape and substance to its successor by a pan-Indian entry into the national Communal violence in 2013 ushering in some important changes mainstream politics by the AAP. -

![³>Dbc <^SX´ ^Da @Dxc 8]SXP Saxet) <P\Pcp](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5951/%C2%B3-dbc-sx%C2%B4-da-dxc-8-sxp-saxet-p-pcp-3075951.webp)

³>Dbc <^SX´ ^Da @Dxc 8]SXP Saxet) <P\Pcp

% !" ./0 !" SIDISrtVUU@IB!&!!"&#S@B9IV69P99I !%! %! ' ( 56 + +, & '()* # ')- 6.!* * + # $%&$$& '&$ -, ,% &% & $ , , % , &, % + , ## , $ N$% $O ,%$# $ , & 8, - 9 8 /%/ $.12 & 134 5 $60/ "" 7 - 7 - 78982:; 52 Q !! R paper audit trail issue, voting percentage in the five phases, # $ pposition parties have besides the reports about the ! Oscheduled a meeting on Andhra Pradesh Assembly # May 21, two days ahead of the election results. $% &' Lok Sabha results, to prepare a The Rahul-Naidu meeting &(' plan to approach the President comes a day after TRS chief K '* of India in case the BJP-led Chandrashekhar Rao met * , NDA is not able to cross Kerala Chief Minister Vijayan '' halfway mark in the Lok Sabha Pinarayi to revive the formation ''-&. to impress upon him not to call of a non-BJP and non- the single largest party to form Congress Federal Front at the /#0 1 a Government. Centre. Political sources said 232 Andhra Pradesh Chief though KCR has always been **(. Minister N Chandrababu seen “close” to the NDA fold, * Naidu, who has been toiling his meeting with Vijayan '4* hard to unite the Opposition, opened the possibility of him ' called on Congress president joining the Congress-led ' (. Rahul Gandhi on Wednesday Opposition camp as Left may and discussed plans to hold the not support the BJP. Naidu headed for West Bengal meeting. The Lok Sabha has 543 to attend public rallies in sup- “Naidu and Rahul dis- elected members and the port of Chief Minister Mamata cussed the post-poll scenario majority mark stands at 272. Banerjee for the next two days. and more or less agreed to call The BJP had won majority in Sources said in case the a meeting of Opposition par- the 2014 general elections with May 23 result throws split ver- ties on May 21,” said AICC 282 seats and the combined dict, 21 Opposition parties are leader. -

Coalition Governments in India: an Evaluation of United Progressive Alliance Government -1

COALITION GOVERNMENTS IN INDIA: AN EVALUATION OF UNITED PROGRESSIVE ALLIANCE GOVERNMENT -1 SUBMITT&O )N {^/tRTlACIULFILLMEN liREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF (i^i m ^ 3n » POLITICAL SCIENCE By AgM^ QAZI Under the Supervision of Dr. IFTEKHAR AHEMMED (ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR) DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY AUGARH (INDIA) 2014 2 4 NCV 2014 DS4380 il Q © ® © ® e Dr. IFTEKHARAHEMMED Telephones: Associate Professor Chairman: 0571-2^01720 DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AMUPABX: 700916/7000920-21-22 Aligarh Muslim University Chairman: 1561 Aligarh - 202002 Office: 1560 <Date: •>^/ij_^l^^^9 Certificate '> . Tliis is io certify tHat^tHe (Dissertation *CoaQ.tion governments in India: Jin ^abuUion of Vnited (Progressive At^nce government - I" Sy !Wr. Mudam' Jifimad Qizi is the originaC researcd wor^ of the candidate, and is suitaMe for submission as the partiaCfidfittmentfor the award of the (Degree of Master of (PhUosophy in (PoCiticaCScienc^. ^i } tg O' /• yr-5S Dr. Iftekhar Ahemmed (Supervisor) DECLARATION I hereby declare that the dissertation "Coalition Governments in India: An Evaluation of United Progressive Alliance Government-I" submitted for the award of the degree of Master of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science is based on my original research work and the dissertation has not been presented for any other degree of this University or any other University or Institution and that all sources used in this work have been thoroughly acknowledged. Place: A w^ vJ /NUcv^^^ MudaHfAhmad Qazi Date: 9o | ) o | >o \<^ -

'Federal Front Can Become a Reality'

10 DEMOCRACY AT WORK MUMBAI | 20 JANUARY 2019 1 > Anxious ticket seekers DID THEY REALLY SAY THAT? CHECKLIST As election fever rises, so does the anxiety of ticket seekers. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) President Amit Shah was in hospital suffering from flu but even here, people GATHBANDHAN-MAKING: ALLIANCES IN THE PIPELINE wanting to press their claims for a BJP nomination in the Lok Sabha simply would- I Tamil Nadu: efforts are on to forge an alliance Ittehadul Muslimeen, YSR Congress and others. n’t stop calling on him. The BJP is facing a funny kind of problem: Following between the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Pawan Kalyan’s Jana Sena has not yet indicate announcements by a handful of its senior leaders that they would not fight the Lok All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam which way it will go Sabha elections, the party is besieged with people wanting to become their replace- (AIADMK), currently in power in the state. The Bihar: All the parties opposed to the BJP-Janata CHATTERBOX ments. The problem is particularly acute in Uttarakhand where at least out of five BJP problem is, the BJP has had a past history of Dal United alliance have come out and formed an MPs — General BC Khanduri and BS Koshiyari — have said they will not contest the committing itself to a Kazhagangal illa alliance. JDU leader Nitish Kumar is dismissive 2019 elections. The same is the case with Vidisha represented by Sushma Swaraj and Tamizhagam (a Kazhagam-less Tamil Nadu). And about the front. Jhansi where Uma Bharati became an MP. -

Understanding the Concept of Cooperative Federalism in the Contemporary Context

SANSHODHAN : 2020 - 21 (VOL.NO. 10) ISSN 2249-8567 UNDERSTANDING THE CONCEPT OF COOPERATIVE FEDERALISM IN THE CONTEMPORARY CONTEXT Dr. Pravin Bhagdikar Introduction: Center and the States and the third is the The Indian Constitution adopted a principle of disintegration of the federal system. parliamentary system at the central and state The influence of the Indian partisan system on levels. In the parliamentary system, elections are the federal system can be examined in the above held at the central level for the Lok Sabha and at context. the state level for the Legislative Assembly. In By 1967, Nehru's personality had elections, a hung Lok Sabha or Vidhan Sabha is dominated the Congress at the Center and in the formed when one party does not get a majority. states. The federal system seems to be affected From then on, the process of forming a front by the monopoly power of the Congress. Dr. between the political party and the party According to Fulchand, "India's federal structure leadership begins. After the formation of the looked like an integrated structure. Although the alliance, the President or the Governor is Center could not impose its will on the states informed about it by the leaders of the alliance. A through the constitution, it was imposing its will coalition government is formed under the through partisan means. India, which was leadership of the Prime Minister at the Center theoretically federal, was an integrated system in and the Chief Minister in the State. A coalition is practice."1 a form of government in which at least two He had a majority in Parliament and the parties come together to govern. -

Appendix A: Ethnic and Regional Parties That Won

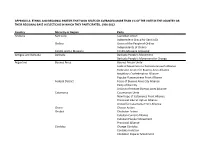

APPENDIX A: ETHNIC AND REGIONAL PARTIES THAT WON SEATS OR AVERAGED MORE THAN 1% OF THE VOTE IN THE COUNTRY OR THEIR REGIONAL BASE IN ELECTIONS IN WHICH THEY PARTICIPATED, 1990-2012 Country Minority or Region Party Andorra Sant Julià Lauredian Union Independent Group for Sant Julià Ordino Union of the People of Ordino Independents of Ordino Canillo and La Massana Canillo-Massana Grouping Antigua and Barbuda Barbuda Barbuda People's Movement Barbuda People's Movement for Change Argentina Buenos Aires Buenos Airean Unity Federal Movement to Recreate Growth Alliance Federalist Action for Buenos Aires Alliance Neighbors Confederation Alliance Popular Bueonsairean Front Alliance Federal District Force of Buenos Aires City Alliance Party of the City Union to Recreate Buenos Aires Alliance Catamarca Catamarcan Unity New Hope of Catamarca Front Alliance Provincial Liberal Option Alliance United for Catamarca Front Alliance Chaco Chacan Action Chubut Chubutan Action Cubutan Current Alliance Cubutan Popular Movement Provincial Alliance Córdoba Change Córdoba Córdoba in Action Córdoban Popular Movement Country Minority or Region Party The People First – Neighborly Union of Córdoba Alliance Together for Córdoba Alliance Union for Córdoba Alliance Corrientes Autonomous Liberal Pact-Popular Democratic Autonomous Liberal Pact-Progressive Democrat- Christian Democrat Civic and Social Front of Corrientes Corrientan Action Corrientan Front Corrientes Project Front Alliance Liberal-Autonomist Pact-Progressive Democratic-Union of the Democratic Center Alliance -

Parliamentary Documentation Vol. XXXVIII 16-31 March 2012 No.6

Parliamentary Documentation Vol. XXXVIII 16-31 March 2012 No.6 AGRICULTURE -AGRICULTURAL CREDIT-(INDIA) 1 KULKARNI, Prabhakar Farm sector loans: A reality check. DECCAN HERALD (BANGALORE), 2012(20.3.2012) Emphasises the need to reconsider the credit reliefs proclaimed in the Union Budget 2012-13 for the benefit of farmers. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Credit-(India); Union Budget- (India). -ANIMAL HUSBANDRY-CRUELTY TO ANIMALS 2 MAHAPRASHASTA, Ajoy Ashirwad Sacred cow. FRONTLINE (CHENNAI), V.29(No.3), 2012(24.2.2012): P.14-18 Expresses concern over the implementation of the Gau-Vansh Vadh Pratished (Sanshodhan) Vidheyak in Madhya Pradesh. ** Agriculture-Animal Husbandry-Cruelty to Animals; Cow Slaughter. -FARMS AND FARMERS 3 GOGOI, Gunjan Integrated farming for nutritional security. ASSAM TRIBUNE (GUWAHATI), 2012(18.3.2012) Highlights the advantages of an integrated farming system ** Agriculture-Farms and Farmers. -FARMS AND FARMERS-FARMERS' SUICIDE 4 CHATTOPADHYAY, Suhrid Sankal Distress and death. FRONTLINE (CHENNAI), V.29(No.3), 2012(24.2.2012): P.33-37 Raises concern over rise in cases of farmers' committing suicide in West Bengal. ** Agriculture-Farms and Farmers-Farmers' Suicide; Agriculture Prices; Agriculture Policy-(India-West Bengal). ** - Keywords 1 -FARMS AND FARMERS-FARMERS’ SUICIDE 5 MUKHERJEE, Uddalak Few more deaths in the granary that feeds Bengal. TELEGRAPH (KOLKATA), 2012(22.3.2012) Identifies the causes of farmers' suicide in Burdwan District of West Bengal. ** Agriculture-Farms and Farmers-Farmers’ Suicide. -FORESTS AND FORESTRY-WILD LIFE 6 SARMA, Jayanta Kumar Man-animal conflict. ASSAM TRIBUNE (GUWAHATI), 2012(18.3.2012) Gives suggestions on the scheme to reduce man-animal conflict in India. -

Mise En Page 1

Print ISSN: 1994-0963 Electronic ISSN: 1994-098X INTER-PARLIAMENTARY UNION CHRONICLE OF PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS 2009 CHRONICLE OF PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS VOLUME 43 Published annually in English and French since 1967, the Chronicle of Parliamentary Elections reports on all national legislative elections held throughout the world during a given year. It includes information on the electoral system, the back- ground and outcome of each election as well as statistics on the results, distri- bution of votes and distribution of seats according to political group, sex and age. The information contained in the Chronicle can also be found in the IPU's data- base on national parliaments, PARLINE. PARLINE is accessible on the IPU web site (http://www.ipu.org/parline) and is continually updated. Inter-Parliamentary Union VOLUME 43 5, chemin du Pommier Case postale 330 CH-1218 Le Grand-Saconnex Geneva – Switzerland Tel.: +41 22 919 41 50 Fax: +41 22 919 41 60 2009 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.ipu.org 2009 Chronicle of Parliamentary Elections VOLUME 43 1 January - 31 December 2009 © Inter-Parliamentary Union 2010 Print ISSN: 1994-0963 Electronic ISSN: 1994-098X Photo credits Front cover: Photo AFP/Pascal Pavani Back cover: Photo AFP/Tugela Ridley Inter-Parliamentary Union Office of the Permanent Observer of 5, chemin du Pommier the IPU to the United Nations Case postale 330 220 East 42nd Street CH-1218 Le Grand-Saconnex Suite 3002 Geneva — Switzerland New York, N.Y. 10017 USA Tel.: + 41 22 919 41 50 Tel.: +1 212 557 58 80 Fax: -

India's National Front and United Front Coalition

INDIA’S NATIONAL FRONT AND UNITED FRONT COALITION GOVERNMENTS A Phase in Federalized Governance M. P. Singh The onset of coalition and minority governments in New Delhi is an important aspect of the paradigmatic shifts in the Indian political system in terms of political federalization and economic liberalization in the 1990s. A political system that previously had functioned as a predominantly parliamentary regime is becoming more federal, and a public (state) sec- tor–dominated planned economy is opening up to market forces both domes- tically and globally. The immediate political context of coalition politics is the decline of the once-dominant Congress Party and the continuing failure of any party from the center, right, or left of the party system to win a working majority of its own to govern India. The recent trends of the metaphors of mandal (affirma- tive action reservations) and mandir (in essence, communalism) and the issue of state autonomy triggered different strategies of mobilization that signifi- cantly transformed the social and psychological bases of politics in India. Besides, a new pattern of social movements centered on single and region- specific issues relating to quality of life (e.g., ecology, gender, utilities, and services), in addition to the older, comprehensive concerns of economic pro- duction and distribution have appeared on the scene. After decades of Congress dominance, coalition or minority governments today must govern India. However, neither coalition politics nor govern- M. P. Singh is Professor of Political Science, University of Delhi, In- dia. An earlier version of this article was delivered at the national seminar on coalition politics in India at the Rajendra Prasad Academy, New Delhi, March 2000.