The Hindutva Doctrine and Bharatiya Janata Party in 2019 Elections in India: Critical Discourse Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Summit & Expo

INTERNATIONAL SUMMIT & EXPO 17th to19th January 2020, Maniram Dewan Trade Centre, Guwahati SupporteD By GOVERNMENT OF ASSAM GOVERNMENT OF MIZORAM GOVERNMENT OF TRIPURA MSME EXPORT PROMOTION COUNCIL (Supported by Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India) (Supported by Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India) International Summit & Expo Start & Stand Up North East 17th to 19th January 2020, Guwahati The North East Region undoubtedly is ready to be counted as an equal in the Start Up and Stand Up revolution. The efforts to nurture “Start Ups” and “Stand Ups” ecosystem in the country, by and large, have been limited to the conventionally bigger cities. Whereas most of these products and execution skills need an active support of mentors who can validate assumptions, help them with strategy and provide them with access to relevant networks. The three-day Summit being organized jointly by MSME Export Promotion Bhubaneswar Kalita Bhubaneswar Kalita Council (Supported by Ministry of MSME, Government of India) the Foundation Member of Parliament 2008-2019 for Millennium Sustainable Development Goals and the Confederation of the CHAIRMAN (Hony) Organic Industry of India in Guwahati on 17th to 19th January 2020 shall provide International Summit & Expo Start & Stand Up North East opportunity to connect with the successful and brightest minds to facilitate how to fuel their business growth. The speakers to be drawn from best breed of entrepreneurs, innovators, venture capitalists, consultants, policy makers both from the Centre and States, academicians, business -

Rikke Alberg Peters

Conjunctions: Transdisciplinary Journal of Cultural Participation Become Immortal! Mediatization and mediation processes of extreme right protest Rikke Alberg Peters This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting all non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited Conjunctions, vol. 2, no. 1, 2015, ISSN 2246-3755, https://doi.org/10.7146/tjcp.v2i1.22274 keywords Right-wing extremism, neo-fascism, protest action, mediation, mediatization, ethno-nationalism abstract Th is paper presents a case study of the German neo-fascist network Th e Immortals (Die Unsterblichen) who in 2011 performed a fl ash-mob, which was disseminated on YouTube for the so-called “Become Immortal” campaign. Th e street protest was designed for and adapted to the specifi c characteristics of online activism. It is a good example of how new contentious action repertoires in which online and street activism intertwine have also spread to extreme right groups. Despite its neo-fascist and extreme right content, the “Become Immortal” campaign serves as an illustrative case for the study of mediated and mediatized activism. In order to analyze the protest form, the visual aesthetics and the discourse of Th e Immortals, the paper mobilizes three concepts from media and communication studies: media practice, mediation, and mediatiza- tion. It will be argued that the current transformation and modernization processes of the extreme right can be conceptualized and understood through the lens of these three concepts. -

Red Alert for 5 Telangana Districts, Yellow For

Follow us on: @TheDailyPioneer facebook.com/dailypioneer RNI No. TELENG/2018/76469 Established 1864 ANALYSIS 7 MONEY 8 SPORTS 12 Published From FUELS UNDER GST: A PROPER HYDERABAD DELHI LUCKNOW BENCHMARKS CLIMB TO NEW LIFETIME BHOPAL RAIPUR CHANDIGARH ILLOGICAL PROPOSITION HIGHS; RIL, IT STOCKS LEAD CHARGE TEST WIN BHUBANESWAR RANCHI DEHRADUN VIJAYAWADA *LATE CITY VOL. 3 ISSUE 318 HYDERABAD, TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 7, 2021; PAGES 12 `3 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable NABHA TO BE MAHESH AND TRIVIKRAM'S SECOND LEAD? { Page 11 } www.dailypioneer.com VHP: RAM TEMPLE FOUNDATION TO BE SC REFUSES TO DEFER NEET-UG CHHATTISGARH GOVERNMENT WAIVES PARTY THAT GETS 120-130 LS SEATS READY BY OCT, ‘GARBHAGRIHA' BY ’23 EXAM SCHEDULED ON SEPTEMBER 12 OUTSTANDING LOAN OF WOMEN SHGS WILL LEAD OPPN FRONT: KHURSHID he foundation of the Rama temple in Ayodhya will be he Supreme Court Monday refused to defer the hhattisgarh Chief Minister Bhupesh Baghel on Monday he Congress is still in the "best position" to clinch 120- completed by the end of September or the first week of National Eligibility-cum-Entrance Test-UG examination, announced waiving off the overdue or unpaid loans 130 seats in the next Lok Sabha elections and assume TOctober and Ram Lalla will be consecrated in the Tscheduled for September 12, saying it does not want to Cworth Rs 12.77 crore of the women SHGs so that they Tthe leadership role in a prospective anti-BJP opposition ‘garbhagriha' (sanctum sanctorum) by December 2023 interfere with the process and it will be "very unfair" to can avail fresh loans to start new economic activities. -

Populism and Fascism

Populism and Fascism An evaluation of their similarities and differences MA Thesis in Philosophy University of Amsterdam Graduate School of Humanities Titus Vreeke Student number: 10171169 Supervisor: Dr. Robin Celikates Date: 04-08-2017 1 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 3 1. Ideology ............................................................................................................................................. 8 1.1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 8 1.2 Populism and fascism as ideologies ........................................................................................................ 9 1.3 The Dichotomies of Populism and Fascism ........................................................................................... 13 1.4 Culture and Nationalism in Populism and Fascism ............................................................................... 19 1.5 The Form of the State and its Role in Security ...................................................................................... 22 1.6 Conclusion ............................................................................................................................................. 25 2. Practice ............................................................................................................................................... -

Epdffile5e1c5329ecfda5.34903735

������������������������ ��������� ����� ��� ���� ��������� ������� ������ �� ��� ����� ����� ����� ����� �� ��� ��� �� ������� ���� ����� ������� �� ��� ���"����� �� ��� ��� ����� �� ��� ���� �������� �� ����� � !"## ����� ��$ !�#" ���� ���� �� ��� ������� ����� ����������� ��!�� ���"������ ���� ���� ��������� ����� %�&�� �� ��� ��� ������ ���� ���������� ��� ������ �� ��'������ � ��� �!�� ����"������ ������ ������ ������ ��&����(����) *�� *�� �� ����#������������ ��� �������� ��� ������ � ������ +�,�� ����������# ������������# ��� ������� ���� ���-�. ��� ����� ����� "���������#;(���"����"����� ��� ���� �/���$ ���0��� ��'��% &������� ����� ����$ ������ ��$ ��� ����� �����<������#!���������� ������� ���� ������� �� ��� ����� ����� �� ����� �/�����$��% �� ��� ���������������$%���������� ��� ������ ����� �� ��'������ �� �&�� !122 �� ������� ���� �� �""���������� ������������������������ ��� ��� �� ������ �������� "����� �����<���#�� ����$ ��� ���������� �� ��� ������ &��� ����� �� ��� �� �� � %�� ���� "������� �� ����� ��� ������� ��������� �� ���� �!�#�������������������� �� �=22 ����� ��� �12= ����� ���� �� ���������� ���� �� ��� ����� ��������# ��� �� ��!�� �� ��� ���"����� �� ������� ���������� ���� ����� ���� �� ����"������ �������� ��!���������#��� ��� �� ��� ���� �� ����� ������ ����� �������� �� ������ ����� �������� � ���� � �� �� ��� ����� �� ���� ����$ ������ �� &����� *���� "���� ����������������� �!���� ��!����!��� !������� �� ��� ����! �� "��" ���� %�� ������� ���� ��� ����� ��� �������� ���� ���� ������� ��� ����� �� ��� -

Marketing Fragment 6 X 10.T65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85081-0 - Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe Cas Mudde Index More information Index Note: Abbreviations of party names are as in the list in the front of the book. abortion 95 asylum seekers 70, 212 Adorno, Theodor 22, 216, 217 Ataka 65, 181 Agir 169 agricultural sector 128 agriculture 127–8 anti-Roma sentiment 87 Albania 51 anti-Semitism 81, 82 Albertazzi, Daniele 56 Christianity and 85 All-Polish Youth 269 economic program 122 al-Qaeda 84 EU membership 164, 165 Altemeyer, Bob 22–3 Islamophobia 84 Americanization 190–2 plebiscitary initiatives 153 Amesberger, Helga 91, 93, 111 protectionism 126 AN 56, 259 recall of MPs 153 in the European Parliament 178, 179 referendums 152 immigration 189 Vienna Declaration 180 the media and 250 AUNS 152, 269 women in the electorate 116 Austria 42, 49, 112, 134, 286 Anastasakis, Othon 5, 32 authoritarianism 22–3, 145–50, 296, Anderson, Benedict 19, 65, 71 300 Andeweg, Rudy B. 34 and electoral success 216–17, 287 Andreas-Hofer-Preis 172 insecurity and 297 ANL 247 studies on 221 Annemans, Gerolf 133, 276 AWS 45, 238, 250 ANO 252 Azione Sociale 180 Antall, Jozef 75 Aznar, Jos´eMar´ıa281 anti-Americanism 77–8 Antic Gaber, Milica 102 Balkans 142, 211, 215 anti-establishment sentiments 221 Ball, Terence 15 anti-globalization movement 7, 196 Baltic states 53–4, 142, 211, 215 anti-racist movements 247 Barber, Benjamin 185 anti-Semitism 22, 79–81, 84 Barney, Darin David 151, 152, 155 globalization and 188, 189, 195 Basques 71 Arab European League, minority rights Bayer, Josef 156 149 BBB 47 Arad, Eyal 84 Belgium 20, 42–3, 49, 51, 192 Arghezi, Mitzura Dominica 98 Bennett, David H. -

Q.1 the India – Uzbekistan Joint Military Exercise Conducted in Foreign Training Node Chaubatia, Ranikhet (Uttarakhand)

Q.1 The India – Uzbekistan joint military exercise conducted in Foreign Training Node Chaubatia, Ranikhet (Uttarakhand). What is the Name of the exercise? भारत - उ煍बेककस्तान संयक्तु सैन्य अभ्यास किदशे ी प्रकशक्षण नोड चौबकतया, रानीखेत (उत्तराखंड) मᴂ अयोकजत हुआ। अभ्यास का नाम क्या ह?ै 1. Simbex/ कसंबेक्स 2. Desert Flag/ डेजर्ट फ्लैग 3. Bongo Sagar/ बोंगो सागर 4. Dustlik II/ डस्र्कलकII 5. Desert Eagle/ डेजर्ट ईगल Ans.4 Q.2 Indian Navy inducted the third Scorpene-class conventional diesel-electric submarine, INS Karanj, into service. It is built by whom? भारतीय नौसेना न े तीसरी स्कॉर्पीन श्रेणी की र्पारंर्पररक डीजल-इलेकक्िक र्पनडुब्बी, आईएनएस करंज को सेिा म ᴂ शाकमल ककया। यह ककसके द्वारा कनकमटत की गई है? 1. GRSE/ जीआरएसई 2. Goa Shipyard/ गोिा कशर्पयाडट 3. Larsen & Toubro/ लासटन एडं र्ुब्रो 4. DRDO/ डीआरडीओ 5. Mazagon Dock/ मझगांि डॉक Ans.5 Q.3 Who has joined the list of the Young Global Leaders (YGL) compiled by the World Economic Forum? कौन किश्व आकथटक मचं द्वारा संककलत यंग ग्लोबल लीडसट (YGL) की सचू ी मᴂ शाकमल हो गई हℂ? 1. Priyanka Chopra/ कप्रयंका चोर्पडा 2. Deepika Padukone/ दीकर्पका र्पादकु ोण 3. Chandrashekhar Azad Ravan/ चंद्रशेखर आजाद रािण 4. Nazhat Shameem/ नजहत शमीम 5. Lijo Jose Pellissery/ कलजो जोस र्पेकलसरी Ans.2 Q.4 Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath inaugurated Rasin Dam and Chillimal Dam in which district? उत्तर प्रदशे के मख्ु यमत्रं ी योगी आकदत्यनाथ न े ककस कजले म ᴂ रकसन बांध और कच쥍लीमल बांध का उद्घार्न ककया? 1. -

REMEMBRANCE Progress," He Said

SUNDAY, JULY 29, 2018 (PAGE 4) DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU From page 1 MISCELLANEOUS PLACEMENT CORRECTION OF NAME Admn initiates proceedings under Code of Omar calls for Oppn unity I No. 4478448Y Hav. Harpreet Singh REQUIRED son of Harchand Singh R/o Kakrali, Required Marketing Executive Minister,” he said. able federal front. Criminal Procedure against 2 contractors Teh & Distt. Ropar, C/o 56APO declare on Distributor Pay Roll in Jammu “Obviously no effort for The National Conference that the name of my son Jashanpreet sive public outcry in the local which includes imprisonment up to for International Brand area and people fear failure of six months and fine or with both. towards opposition unity will vice-president, who called on Singh is wrongly written as Jaspreet really succeed unless the Banerjee at the State Secretariat Singh in official Army record. Applied Min. Qualification:- Matric the projects on account of cost The proceedings under for correction of same. Objection if escalations", read the conditional Section 133 CrPC have also Congress is able to take the fight here yesterday, said he was look- Candidate must have bike to the BJP in the way we hope,” ing forward to working closely any convey to concerned authority order of the District Magistrate. been initiated against another within seven days. Contact: 9906015699 Stating that delay caused by private contractor namely Joy Abdullah said on the sidelines of with her and other like-minded the contractor on important roads Kokhar, a resident of Christian a programme here. leaders in the next Lok Sabha The former Jammu and elections. -

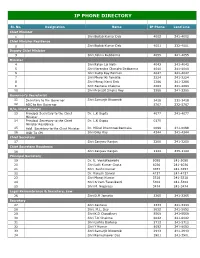

Ip Phone Directory

IP PHONE DIRECTORY Sl. No. Designation Name IP Phone Land Line Chief Minister 1 Shri Biplab Kumar Deb 4002 241-4002 Chief Minister Residence 2 Shri Biplab Kumar Deb 4001 232-4001 Deputy Chief Minister 3 Shri Jishnu Debbarma 4055 241-4055 Minister 4 Shri Ratan Lal Nath 4043 241-4043 5 Shri Narendra Chandra Debbarma 4040 241-4040 6 Shri Sudip Roy Barman 4047 241-4047 7 Shri Mevar Kr Jamatia 3224 241-3224 8 Shri Manoj Kanti Deb 3286 241-3286 9 Smt Santana Chakma 4063 241-4063 10 Shri Pranajit Singha Roy 3366 241-3366 Governor's Secretariat 11 Secretary to the Governor Shri Samarjit Bhowmik 3428 232-3428 12 ADC to the Governor 5767 232-5767 O/o, Chief Minister 13 Principal Secretary to the Chief Dr. L.K Gupta 4077 241-4077 Minister 14 Principal Secretary to the Chief Dr. L.K Gupta 0175 Minister Residence 15 Addl. Secretary to the Chief Minister Dr. Milind Dharmrao Ramteke 0099 241-0099 16 OSD To CM Shri Dilip Ray 4344 241-4344 Chief Secretary 17 Shri Sanjeev Ranjan 3200 241-3200 Chief Secretary Residence 18 Shri Sanjeev Ranjan 1144 235-1144 Principal Secretary 19 Dr. U. Venkateswarlu 5058 241-5058 20 Shri Lalit Kumar Gupta 6036 241-6036 21 Shri Sushil Kumar 3357 241-3357 22 Dr. Rakesh Sarwal 4127 241-4127 23 Shri Manoj Kumar 3318 241-3318 24 Shri Sriram Taranikanti 5304 241-5304 25 Shri M. Nagaraju 3474 241-3474 Legal Remembrance & Secretary, Law 26 Shri D.M Jamatia 3365 241-3365 Secretary 27 Shri Santanu 3333 241-3333 28 Shri. -

Welfare Chauvinism – Who Cares? Evidence on Priorities and the Importance the Public Attributes to Expanding Or Retrenching Welfare Entitlements of Immigrants

Welfare Chauvinism – Who Cares? Evidence on Priorities and the Importance the Public Attributes to Expanding or Retrenching Welfare Entitlements of Immigrants Matthias Enggist University of Zurich August 2019 Abstract In many Western European countries, welfare rights of immigrants have emerged as an important issue on the political agenda, while an extensive body of research has documented growing welfare chauvinistic preferences. However, we do not know much about the importance people attach to welfare chauvinism relative to welfare benefits for other social groups such as pensioners, the unemployed or families. This paper, therefore, addresses the question whether citizens in Western European countries prioritize expanding or restricting welfare entitlements for immigrants. Or do they subordinate this issue to other social policy reforms? Moreover, focusing on priorities allows me to disentangle which proponents of welfare rights for immigrants remain supportive even when rising benefits for immigrants comes at the cost of lowering benefits for themselves and to contribute to the debate whether welfare chauvinism is more strongly correlated with attitudes on an economic-redistributive or socio-cultural dimension. To investigate both the importance of and the priorities for welfare chauvinism, I rely on conjoint experiments and rating questions from an original survey recently fielded in eight Western European countries. I show that welfare chauvinism is indeed one of the social policy reform issues the public has strongest preferences on – more than for example on unemployment benefits or childcare. This despite the share of financial resources benefitting immigrants being relatively small. Importance of welfare chauvinism is high for both its proponents as well as its opponents. -

WING POPULISM: CAPTURING the GLOBE Pratishtha Rao Department of Political Science, University of Delhi

J. S. Asian Stud. 08 (02) 2019. 79-90 DOI: 10.33687/jsas.008.02.3009 Available Online at EScience Press Journal of South Asian Studies ISSN: 2307-4000 (Online), 2308-7846 (Print) https://esciencepress.net/journals/JSAS WING POPULISM: CAPTURING THE GLOBE Pratishtha Rao Department of Political Science, University of Delhi. New Delhi, India. *Corresponding Author Email ID: [email protected] A B S T R A C T This article is an attempt to explore the reasons for the recent trend of the rise of rightwing populism in the whole world. The origin of the terms ‘left’ and ‘right’ dates back to the French Revolution and the seating arrangements. The term ‘right’ was soon understood to mean reactionary or monarchist, and the term ‘left’ implied revolutionary or egalitarian sympathies. While populism is an idea of grouping people against ‘the elites. Both right ideology and populism are based on the segregation of society in two sections. When right wing political ideology merges with populist ideology, it is termed as “Right wing populism”. Right wing populists generally converge on issues like opposing immigration, nativism, protectionism etc. This ideology is gaining popularity rapidly in the present world order. The reasons are many, like social media, print and electronic media, civil society, economic instability, and charismatic leadership. Along with this the article also tries to find out the connection of hatred and human nature with the rise of right-wing populism. It focuses on how when hatred at the international level is justified it gives away for hatred at the domestic level as well which results in the cause and effect of right-wing populism. -

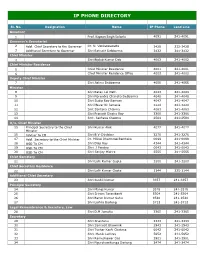

Ip Phone Directory

IP PHONE DIRECTORY Sl. No. Designation Name IP Phone Land Line Governor 1 Prof. Kaptan Singh Solanki 4091 241-4091 Governor's Secretariat 2 Addl. Chief Secretary to the Governor Dr. U. Venkateswarlu 3428 232-3428 3 Additional Secretary to Governor Shri Ratnajit Debbarma 3432 241-3432 Chief Minister 4 Shri Biplab Kumar Deb 4003 241-4002 Chief Minister Residence 5 Chief Minister Residence 4001 241-4001 6 Chief Minister Residence Office 4002 241-4002 Deputy Chief Minister 7 Shri Jishnu Debbarma 4055 241-4055 Minister 8 Shri Ratan Lal Nath 4043 241-4043 9 Shri Narendra Chandra Debbarma 4040 241-4040 10 Shri Sudip Roy Barman 4047 241-4047 11 Shri Mevar Kr Jamatia 3224 241-3224 12 Smt Santana Chakma 4063 241-4063 13 Shri Pranajit Singha Roy 3366 241-3366 14 Smt. Santana Chakma 2584 241-2584 O/o, Chief Minister 15 Principal Secretary to the Chief Shri Kumar Alok 4077 241-4077 Minister 16 Adviser to CM Shri B V Chhibber 3276 241-3276 17 Addl. Secretary to the Chief Minister Dr. Milind Dharmrao Ramteke 0099 241-0099 18 OSD To CM Shri Dilip Ray 4344 241-4344 19 OSD To CM Shri. J Pandya 0043 241-0043 20 OSD To CM Shri Sanjay Mishra 5555 241-5555 Chief Secretary 21 Shri Lalit Kumar Gupta 3200 241-3200 Chief Secretary Residence 22 Shri Lalit Kumar Gupta 1144 235-1144 Additional Chief Secretary 23 Shri Sushil Kumar 3357 241-3357 Principal Secretary 24 Shri Manoj Kumar 3318 241-3318 25 Shri Sriram Taranikanti 5304 241-5304 26 Shri Barun Kumar Sahu 9520 241-9520 27 Shri Laihlia Darlong 5712 241-5712 Legal Remembrance & Secretary, Law 28 Shri D.M Jamatia 3365 241-3365 Secretary 29 Shri Shantanu 3333 241-3333 30 Shri Samarjit Bhowmik 2943 241-2943 31 Shri Tushar Kanti Chakma 6042 241-6042 32 Shri.