A Preliminary Note on Jumli Caste Structure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Berkeley Room One Thousand

UC Berkeley Room One Thousand Title Kingship, Buddhism and the Forging of a Region Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8vn4g2jd Journal Room One Thousand, 3(3) ISSN 2328-4161 Author Hawkes, Jason Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Jason Hawkes Kingship, Buddhism and the MedievalForging Pilgrimage of a inRegion West Nepal West Nepal provides a unique space to think about pilgrimage in the past. For many centuries, this central Himalayan region lay at the fringes of neighboring states. During the 13th century CE, the Khasa Malla dynasty established a kingdom here with seasonal capitals at Sinja and Dullu, which soon grew to encompass the entire region as well as parts of India and Tibet (Adhikary 1997; Pandey 1997) (Figure 1). With these developments, the region became a key zone of interaction. Capitalizing on pre-existing routes and connections, it connected India to the Silk Road, and provided a conduit for the spread and survival of Indian Buddhism. Pilgrimage would have been an important component of the movement of people and ideas within and across the region— interactions that shaped the socio-cultural and economic dynamics of the area. However, due to its liminal position, the study of West Nepal has been neglected in favor of more ‘important’ neighboring regions. As such, we have only n outline understanding of pilgrimage and the societal framework within which it took place. The monuments built during the reign of the Khasa Malla provide tantalizing clues that can be used to study pilgrimage and the movement Figure 1 243 Jason Hawkes of people and ideas in the Himalaya. -

Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-Kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L

Western Washington University Western CEDAR A Collection of Open Access Books and Books and Monographs Monographs 2008 Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L. Curley Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks Part of the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Curley, David L., "Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal" (2008). A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs. 5. https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Books and Monographs at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents Acknowledgements. 1. A Historian’s Introduction to Reading Mangal-Kabya. 2. Kings and Commerce on an Agrarian Frontier: Kalketu’s Story in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 3. Marriage, Honor, Agency, and Trials by Ordeal: Women’s Gender Roles in Candimangal. 4. ‘Tribute Exchange’ and the Liminality of Foreign Merchants in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 5. ‘Voluntary’ Relationships and Royal Gifts of Pan in Mughal Bengal. 6. Maharaja Krsnacandra, Hinduism and Kingship in the Contact Zone of Bengal. 7. Lost Meanings and New Stories: Candimangal after British Dominance. Index. Acknowledgements This collection of essays was made possible by the wonderful, multidisciplinary education in history and literature which I received at the University of Chicago. It is a pleasure to thank my living teachers, Herman Sinaiko, Ronald B. -

Is Friday the 13Th an Unlucky Day?

Is Friday the 13th an unlucky day? Posted by Jacqui Atkielski On 05/13/2016 HOLLYWOOD, MD-- Some will call today the unluckiest day of the year. If you’re a believer, try to not step on sidewalk cracks, walk under ladders, break mirrors or encounter any black cats. Fear of Friday the 13th, or paraskevidekatriaphobia, has spawned a horror movies franchise and a tradition of widespread paranoia when it comes up on the calendar. If a month starts on a Sunday, you’ll have a Friday the 13th in that month. Folklore historians say it’s difficult to determine how the taboo came to be. Many believe that it originates from the Last Supper, and the 13 guests that sat at the table on the day before the Friday on which Jesus was crucified, according to Time. What began as a Christian interpretation leads some modern Americans to avoid staying at hotel rooms with the number 13, venturing above the 13th floor of a building, and won’t sit in the 13th row of an airplane. beware of venturing up to the 13th floor of any building or try not to sit in the 13th row in airplanes. There is historic proof that people may have feared Friday the 13th, according to another Time article. On a Friday the 13th in 1307, thousands of Knights Templar were arrested on orders from King Philip IV of France because of suspicions that their secret initiation rituals made them enemies of the faith. After years of torture, they were burned at the stake. -

Cultural Crisis of Caste Renouncer: a Study of Dasnami Sanyasi Identity in Nepal

Molung Educational Frontier 91 Cultural Crisis of Caste Renouncer: A Study of Dasnami Sanyasi Identity in Nepal Madhu Giri* Abstract Jat NasodhanuJogikois a famous mocking proverb to denote the caste status of Sanyasi because the renouncer has given up traditional caste rituals set by socio-cultural institutions. In other cultural terms, being Sanyasi means having dissociation himself/herself with whatever caste career or caste-based social rank one might imagine. To explore the philosophical foundation of Sanyasi, they sacrificed caste rituals and fire (symbol of power, desire, and creation). By the virtues of sacrifice, Sanyasi set images of universalism, higher than caste order, and otherworldly being. Therefore, one should not ask the renouncer caste identity. Traditionally, Sanyasi lived in Akhada or Matha,and leadership, including ownership of the Matha transformed from Guru to Chela. On the contrary, DasnamiMahanta started marital and private life, which is paradoxical to the philosophy of Sanyasi.Very few of them are living in Matha,but the ownership of the property of Mathatransformed from father to son. The land and property of many Mathas transformed from religious Guthi to private property. In terms of cultural practices, DasnamiSanyasi adopted high caste culture and rituals in their everyday life. Old Muluki Ain 1854 ranked them under Tagadhari, although they did notassert twice-born caste in Nepal. Central Bureau of Statistics, including other government institutions of Nepal, listed Dasnamiunder the line ofChhetri and Thakuri. The main objective of the paper is to explore the transformation of Dasnami institutional characteristics and status from caste renunciation identity to caste rejoinder and from images of monasticism, celibacy, universalism, otherworldly orientation to marital, individualistic lay life. -

The Dread Taboo, Human Sacrifice, and Pearl Harbor

The Dread Taboo, Human Sacrifice, and Pearl Harbor RDKHennan The word taboo, or tabu, is well known to everyone, but it is especially interesting that it is one of but two or possibly three words from the Polynesian language to have been adopted by the English-speaking world. While the original meaning of the taboo was "Sacred" or "Set apart," usage has given it a decidedly secular meaning, and it has become a part of everyday speech all over the world. In the Hawaiian lan guage the word is "kapu," and in Honolulu we often see a sign on a newly planted lawn or in a park that reads, not, "Keep off the Grass," but, "Kapu." And to understand the history and character of the Hawaiian people, and be able to interpret many things in our modern life in these islands, one must have some knowledge of the story of the taboo in Hawaii. ANTOINETTE WITHINGTON, "The Dread Taboo," in Hawaiian Tapestry Captain Cook's arrival in the Hawaiian Islands signaled more than just the arrival of western geographical and scientific order; it was the arrival of British social and political order, of British law and order as well. From Cook onward, westerners coming to the islands used their own social civil codes as a basis to judge, interpret, describe, and almost uniformly condemn Hawaiian social and civil codes. With this condemnation, west erners justified the imposition of their own order on the Hawaiians, lead ing to a justification of colonialism and the loss of land and power for the indigenous peoples. -

Pramod Thapa Somnath Aryal

Pramod Thapa Jr. Officer Email: [email protected] Somnath Aryal Officer Account Department Account Email: [email protected] Kush Sunder Shrestha Sr. Admin Officer Email: [email protected] Basanta Blown Officer Email: [email protected] Administration Chintamani Rijal Asst. Coordinator Email: [email protected] Nil Prasad Subedi Jr. Officer Email: [email protected] Parmila Rai Officer Email: [email protected] Administration Ravi Khadka Supervisor Pradeep Khadka Support Staff Narayan Budhathoki Support Staff Administration Narayan Mangrati Support Staff Naresh Kumar Sunuwar Support Staff Shani Kumar Khulal Support Staff Administration Basulal Deula Support Staff Surya Bahadur Thapa Support Staff Administration Abani Tandukar Sr. Officer Counseling Subash Chandra Pandey Discipline Incharge Khindra Kafle Discipline Supervisor Discipline Sangita Dhakal Discipline Staff Hari Prasad Niraula Head, ECA ECA Email: [email protected] Mukesh Chandra System Administrator Email: [email protected] IT Department Govinda Aryal Officer Email: [email protected] Examination Indu Shrestha Officer Email: [email protected] Mousami Shreepali Jr. Officer Email: [email protected] Desk Santoshi Bist – Jr. Officer Email: [email protected] Front Rabina Shakya Jr. Officer Umesh Karmacharya Support Staff Gardening Basundhara Chhetri Hostel Supervisor, Girls Bhagwati Khatri Support Staff Hostel Durga Basnet Support Staff Suraj Air Hostel Supervisor, Boys Hostel Chandra Bahadur Gurung Lab Assistant, Biology Navaraj Lamichhane Lab Assistant, Microbiology Laboratory Shisam Shrestha Lab Assistant, Chemistry Giriraj Pokhrel Officer Email: [email protected] Library Sunita Shrestha Officer Email: [email protected] Shambhu Singh Maharjan Storekeeper Store Email: [email protected] Bishnu Raya Head Bus Driver Balaram Thapa Bus Driver Transportation Raj Kumar Khadka Bus Driver Bishwash Chaudhari Support Staff Chhiring Tamang Support Staff Transportation Subash Tharu Support Staff Chandan Deula Parking Staff Bijay Thapa Support Staff Transportation. -

Appraisal of the Karnali Employment Programme As a Regional Social Protection Scheme

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aston Publications Explorer Appraisal of the Karnali Employment Programme as a regional social protection scheme Kirit Vaidya in collaboration with Punya Prasad Regmi & Bhesh Ghimire for Ministry of Local Development, Government of Nepal & ILO Office in Nepal November 2010 Copyright © International Labour Organization 2010 First published 2010 Publications of the International Labour Offi ce enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authoriza- tion, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Offi ce, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Offi ce welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with reproduction rights organizations may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to fi nd the reproduction rights organization in your country. social protection / decent work / poverty alleviation / public works / economic and social development / Nepal 978-92-2-124017-4 (print) 978-92-2-124018-1 (web pdf) ILO Cataloguing in Publication Data The responsibility for opinions expressed in signed articles, studies and other contributions rests solely with their authors, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Offi ce of the opinions expressed in them. Reference to names of fi rms and commercial products and processes does not imply their endorsement by the International Labour Offi ce, and any failure to mention a particular fi rm, commercial product or process is not a sign of disapproval. -

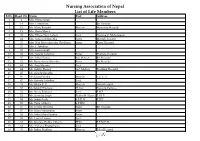

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 1 2 Mrs. Prema Singh 2 14 Mrs. I. Mathema Bir Hospital 3 15 Ms. Manu Bangdel Matron Maternity Hospital 4 19 Mrs. Geeta Murch 5 20 Mrs. Dhana Nani Lohani Lect. Nursing C. Maharajgunj 6 24 Mrs. Saraswati Shrestha Sister Mental Hospital 7 25 Mrs. Nati Maya Shrestha (Pradhan) Sister Kanti Hospital 8 26 Mrs. I. Tuladhar 9 32 Mrs. Laxmi Singh 10 33 Mrs. Sarada Tuladhar Sister Pokhara Hospital 11 37 Mrs. Mita Thakur Ad. Matron Bir Hospital 12 42 Ms. Rameshwori Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 13 43 Ms. Anju Sharma Lect. 14 44 Ms. Sabitry Basnet Ast. Matron Teaching Hospital 15 45 Ms. Sarada Shrestha 16 46 Ms. Geeta Pandey Matron T.U.T. H 17 47 Ms. Kamala Tuladhar Lect. 18 49 Ms. Bijaya K. C. Matron Teku Hospital 19 50 Ms.Sabitry Bhattarai D. Inst Nursing Campus 20 52 Ms. Neeta Pokharel Lect. F.H.P. 21 53 Ms. Sarmista Singh Publin H. Nurse F. H. P. 22 54 Ms. Sabitri Joshi S.P.H.N F.H.P. 23 55 Ms. Tuka Chhetry S.P.HN 24 56 Ms. Urmila Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 25 57 Ms. Maya Manandhar Sister 26 58 Ms. Indra Maya Pandey Sister 27 62 Ms. Laxmi Thakur Lect. 28 63 Ms. Krishna Prabha Chhetri PHN F.P.M.C.H. 29 64 Ms. Archana Bhattacharya Lect. 30 65 Ms. Indira Pradhan Matron Teku Hospital S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 31 67 Ms. -

Some Notes on Nepali Castes and Sub-Castes—Jat and Thar

SOME NOTES ON NEPALI CASTES AND SUB-CASTES- JAT AND THAR. - Suresh Singh This paper attempts to make a re-presentation of evolution and construction of Jat and Thar system among the Parbatya or hill people of Nepal. It seeks to expose the reality behind the myth that the large number of Aryans migrated from Indian plains due to Muslim invasion and conquered to become the rulers in Nepal, and the Mongoloids were the indigenous people. It also seeks to show the construction and reconstruction of identity of the different castes (Jats) and subcastes (Thars). The Nepalese history is lost in legends and fables. Archaeological data, which might shed light on the early years, are practically nonexistent or largely unexplored, because the Nepalese Government has not encouraged such research within its borders. However, there seem to be a number of sites that might yield valuable find, once proper excavation take place. Another problem seems to be that history writing is closely connected with the traditional conception of Nepali historiography, constructed and intervened by the efforts of the ruling elite. Many of the written documents have been re-presented to legitimatize the ruling elite’s claim to power. As it is well known from political history, the social history, too, becomes an interpretation from the view of the Kathmandu valley, and from the Indian or alleged Indian immigrants and priestly class. It is difficult to imagine, that Aryans came to Nepal in greater numbers about 600 years ago, and because of their mental superiority and their noble character, they were asked by the people to become the rulers of their small states. -

First Draft of the Report Was Prepared

i Study on the New and Emerging Trends of Human Trafficking in Entertainment Sectors in Nepal Study on the NEW AND EMERGING TRENDS OF HUMAN TRAFFICKING IN ENTERTAINMENT SECTORS IN NEPAL Submitted to: Forum for Protection of People’s Rights (PPR-Nepal) Submitted by: Kapil Aryal Nepal Institute for Training and Research Kathmandu March 20, 2020 NEW AND EMERGING TRENDS OF HUMAN TRAFFICKING IN ENTERTAINMENT SECTORS IN NEPAL i ii Study on the New and Emerging Trends of Human Trafficking in Entertainment Sectors in Nepal Research Team Lead Researcher : Kapil Aryal, Associate Professor, Kathmandu School of Law Researchers : Satish Kumar Sharma, Director, PPR Nepal Neha Sharma, NTV Journalist Aashish Panta, Advocate Data Analyst : Manas Wagley Administrative and Logistic Support Anupama Subba Daya Sagar Dahal Contact Forum for Protection of People’s Rights – Nepal P.O. Box 24926, Baneshwor, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: +977-01-4464100 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Website: www.pprnepal.org.np March, 2020, Kathmandu DISCLAIMER This study is made possible by the generous support of the American people and British people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (UK aid). The contents of the study on The New and Emerging Trends of Human Trafficking in Entertainment Sectors in Nepal are the responsibility of Forum for Protection of People’s Rights (PPR) and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government or UK aid or the United Kingdom Government. ii iii Study on the New and Emerging Trends of Human Trafficking in Entertainment Sectors in Nepal FOREWORD AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Forum for Protection of People’s Rights (PPR), a non-governmental, non-profit organization established in 2002 to advocate and work in the area of human rights and access to justice has been carrying out several research and activities against human trafficking. -

Jumla Community Development Project a Project Proposal

Jumla Community Development Project A Project Proposal April 2011 – December 2014 by Govinda Development Aid Association, Aalen, Germany in cooperation with Shangrila Association, Jumla, Nepal Jumla Community Development Project • April 2011 – December 2014 2 Table of contents 1. Background..........................................................................................6 2. Problems, opportunities and development intervention..................7 3. Project Beneficiaries.........................................................................12 4. Project Description............................................................................12 4.1 Project goal .....................................................................................13 4.2 Project purposes/ outcomes..........................................................13 4.3 Project Outputs ...............................................................................14 4.4 Project Activities.............................................................................15 5. Project Methodology .........................................................................24 5.1 Self-help groups and Cooperative organization ..........................25 5.2 Horizontal learning .........................................................................25 5.3 Affirmative action............................................................................25 5.4 Use of different methods in awareness and educative process 25 5.5 Team building and office set up ....................................................26 -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014.