Ilissos River

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEW EOT-English:Layout 1

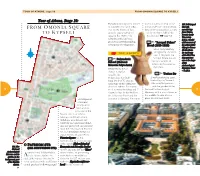

TOUR OF ATHENS, stage 10 FROM OMONIA SQUARE TO KYPSELI Tour of Athens, Stage 10: Papadiamantis Square), former- umental staircases lead to the 107. Bell-shaped FROM MONIA QUARE ly a garden city (with villas, Ionian style four-column propy- idol with O S two-storey blocks of flats, laea of the ground floor, a copy movable legs TO K YPSELI densely vegetated) devel- of the northern hall of the from Thebes, oped in the 1920’s - the Erechteion ( page 13). Boeotia (early 7th century suburban style has been B.C.), a model preserved notwithstanding 1.2 ¢ “Acropol Palace” of the mascot of subsequent development. Hotel (1925-1926) the Athens 2004 Olympic Games A five-story building (In the photo designed by the archi- THE SIGHTS: an exact copy tect I. Mayiasis, the of the idol. You may purchase 1.1 ¢Polytechnic Acropol Palace is a dis- tinctive example of one at the shops School (National Athens Art Nouveau ar- of the Metsovio Polytechnic) Archaeological chitecture. Designed by the ar- Resources Fund – T.A.P.). chitect L. Kaftan - 1.3 tzoglou, the ¢Tositsa Str Polytechnic was built A wide pedestrian zone, from 1861-1876. It is an flanked by the National archetype of the urban tra- Metsovio Polytechnic dition of Athens. It compris- and the garden of the 72 es of a central building and T- National Archaeological 73 shaped wings facing Patision Museum, with a row of trees in Str. It has two floors and the the middle, Tositsa Str is a development, entrance is elevated. Two mon- place to relax and stroll. -

Tragedies. with an English Translation by Frank Justus Miller

= 00 I CM CD CO THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY KOCNDED BY JAMES LOEB, LL.D. EDITED BY tT. E. PAGE, C.H., LJTT.D. E. CAPPS. PH.D., IX. D. \V. H. D. ROLSE, Ltrr.i). SENECA'S TRAGEDIES I SENECA'S TRAGEDIES WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY FRANK JUSTUS MILLER, Ph.D., LL.D. FBOrSSSOR IS TH« UNIVKBSlfY Or CHICAGO IN TWO VOLUMES I HERCULES FURENS TROADES MEDEA HIPPOLYTUS OEDIPUS LONDON WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS liCMXXXVIIl PR S/./ Co p. ^ First Printed, 1917. Reprinted, 1927, 1938. PRINTED IN GEEAT BRITAIN CONTENTS PAGE INTRODCCnON vii BIBUOGRAPHY XiU HKRCCLES FURE.NS 1 TROADES 121 MEDEA 225 HIPPOLYTLS 317 OEDIPUS 425 APPKKDIX. COMPARATIVE ANALYSES 525 INTRODUCTION Lucius Annaeus Sexeca, commonly called the Philosopher to distinguish him from his father, Marcus Annaeus Seneca, the Rhetorician, was bom close to the beginning of the Christian era, whether shortly before or shortly after is not certain. He, as was his father before him. was born at Cordova in Spain, the birthplace also of his brilliant nephew, Marcus Annaeus Lucanus. Other notable Spaniards in Roman literature were Columella, born in Gades, Martial, in Bilbilis, and Quintilian, in Calagurris. The younger Seneca was brought to Rome in early infancy and received his training there. He was a Senator under Caligula and Claudius, and in 41 A.D., through the machinations of Messalina, was ordered by the emperor into exile at Corsica. Thence he was recalled in 49 through the in- fluence of Agrippina, now the wife of Claudius, and to him was entrusted the education of Agrippina's son, Domitius, afterwards the emperor Xero. -

Plant and Garden Imagery in Plato's Phaedrus

From the Plane Tree to the Gardens of Adonis: Plant and Garden Imagery in Plato’s Phaedrus By Daniel Carey Supervised by Dennis J. Schmidt Submitted in fulfilment for the requirements of the degree of Master of Research School of Humanities and Communication Arts WESTERN SYDNEY UNIVERSITY 2021 For Torrie 2 Acknowledgements A project like this would not have been completed without the help of some truly wonderful people. First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Dennis J. Schmidt, for his patience, excitement, and unwavering commitment to my work. This thesis was initially conceived as a project on gardening in the history of philosophy, although it quickly turned into an examination of plant and garden imagery in Plato’s dialogue the Phaedrus. If not for Denny’s guiding hand I would not have had the courage to pursue this text. Over this past year he has taught me to appreciate the art of close reading and pushed me to think well beyond my comfort levels; for that, I am eternally grateful. I would also like to thank Professor Drew A. Hyland, who through the course of my candidature, took the time to answer several questions I had about the dialogue. In addition, I would like to thank Associate Professors Jennifer Mensch and Dimitris Vardoulakis. While they might not have had any direct hand in this project, my time spent in their graduate classes opened my eyes to new possibilities and shaped my way of thinking. Last but not least, I owe a great debt of thanks to Dr. -

Journal Volume 5, Issue 2, June 2015

1 Journal of Regional Socio-Economic Issues, Volume 5, Issue 2, June 2015 Journal of Regional Socio-Economic Issues, Volume 5, Issue 2, June 2015 2 JOURNAL OF REGIONAL SOCIO- ECONOMIC ISSUES (JRSEI) Journal of Regional & Socio-Economic Issues (Print) ISSN 2049-1395 Journal of Regional & Socio-Economic Issues (Online) ISSN 2049-1409 Indexed by Copernicus Index, DOAJ (Director of Open Access Journal), EBSCO, Cabell’s Index The journal is catalogued in the following catalogues: ROAD: Directory of Open Access Scholarly Resources, OCLC WorldCat, EconBiz - ECONIS, CITEFACTOR, OpenAccess 3 Journal of Regional Socio-Economic Issues, Volume 5, Issue 2, June 2015 JOURNAL OF REGIONAL SOCIO-ECONOMIC ISSUES (JRSEI) ISSN No. 2049-1409 Aims of the Journal: Journal of Regional Socio-Economic Issues (JRSEI) is an international multidisciplinary refereed journal the purpose of which is to present papers manuscripts linked to all aspects of regional socio-economic and business and related issues. The views expressed in this journal are the personal views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of JRSEI journal. The journal invites contributions from both academic and industry scholars. Electronic submissions are highly encouraged (mail to: [email protected]). Chief-Editor Prof. Dr. George M. Korres: Professor University of the Aegean, School of Social Sciences, Department of Geography, [email protected] Editorial Board (alphabetical order) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Zacharoula S. Andreopoulou, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Faculty of Forestry and Natural Environment, School of Agriculture, Forestry & Natural Environment, [email protected] Dr. Stilianos Alexiadis, Ministry of Reconstruction of Production, Environment & Energy Department of Strategic Planning, Rural Development, Evaluation & Documentation Division of Documentation & Agricultural Statistics, [email protected]; [email protected]; Assoc. -

Scope, Basic Objectives and Methodology of the Research

ORGANISATION FOR PLANNING AND ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION OF ATHENS NTUA – URBAN ENVIRONMENT LABORATORY RESEARCH PROJECT METROPOLITAN PARK AT GOUDI – ILISOS, ATHENS SUMMARY PRESENTATION 2002 1 SCOPE, BASIC OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY OF THE RESEARCH In November 1997, the Organisation for Planning and Environmental Protection of Athens (Athens Organisation) assigned to the Urban Environment Laboratory of the Department of Urban and Regional Planning, of the NTUA School of Architecture, a Research Project entitled “Metropolitan Park at Goudi”. This project was completed in May 1999. The Design Area extends south-east of Messoghion Avenue, on both sides of Katekhaki Avenue upto the foot of Hymettus mountain, and includes the areas of the former and present military camps of Varyti, Zorba, Fakinou and Plessa, the Pentagon, the Zographou Technical University Campus, the Centre for Medical- Biological Research of the Academy of Athens, the University Research Institute of Mental Health of the University of Athens; the ‘Red Cross’, ‘People’s’, ‘Children’s’, ‘General State’ and ‘Sotiria’ civil hospitals; the 401 General Army and 251 General Navy military hospitals; the ministries of Public Order, National Defence, Justice and Transport (under construction); the Greek Radio Television S.A. complex (former Armed Forces Information Service); the Gendarmerie School and Grove; the Papagou Grove; the sports grounds of the Municipalities of Athens, Zographou and Papagou; the nursery garden of the Municipality of Athens; the Riding Centre of the Athletics General Secretariat; schools of the adjacent Municipalities; and, finally, the forest and grassland expanses of the Officers’ Independent Construction Organisation (AOOA). The overall expanse of the Design Area is approximately 4,500,000 sq.m. -

Preliminary Flood Risk Assessment: the Case of Athens

Preliminary flood risk assessment: the case of Athens Georgia Kandilioti & Christos Makropoulos Natural Hazards Journal of the International Society for the Prevention and Mitigation of Natural Hazards ISSN 0921-030X Nat Hazards DOI 10.1007/s11069-011-9930-5 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer Science+Business Media B.V.. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your work, please use the accepted author’s version for posting to your own website or your institution’s repository. You may further deposit the accepted author’s version on a funder’s repository at a funder’s request, provided it is not made publicly available until 12 months after publication. 1 23 Author's personal copy Nat Hazards DOI 10.1007/s11069-011-9930-5 ORIGINAL PAPER Preliminary flood risk assessment: the case of Athens Georgia Kandilioti • Christos Makropoulos Received: 3 May 2010 / Accepted: 8 August 2011 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2011 Abstract Flood mapping, especially in urban areas, is a demanding task requiring sub- stantial (and usually unavailable) data. However, with the recent introduction of the EU Floods Directive (2007/60/EC), the need for reliable, but cost effective, risk mapping at the regional scale is rising in the policy agenda. Methods are therefore required to allow for efficiently undertaking what the Directive terms ‘‘preliminary flood risk assessment,’’ in other words a screening of areas that could potentially be at risk of flooding and that consequently merit more detailed attention and analysis. -

Water Management and Its Judicial Contexts in Ancient Greece: a Review from the Earliest Times to the Roman Period

1 Water Management and its Judicial Contexts in Ancient Greece: A Review from the Earliest Times to the Roman Period Jens Krasilnikoff1 and Andreas N. Angelakis2 1 Department of History and Classical Studies, School of Culture and Society, Aarhus University, 8000 Aarhus C, Denmark; [email protected] 2 Institute of Crete, National Foundation for Agricultural Research (N.AG.RE.F.), 71307 Iraklion and Hellenic Union of Municipal Enterprises for Water Supply and Sewerage, Larissa, Greece; [email protected] Abstract: Ancient Greek civilizations developed technological solutions to problems of access to and disposal of water but this prompted the need to take judicial action. This paper offers an overview of the judicial implications of Ancient civilizations developments or adaptations of technological applications aimed at exploiting natural resources. Thus, from the earliest times, Greek societies prepared legislation to solve disputes, define access to the water resources, and regulate waste- and storm-water disposal. On the one hand, evidence suggests that from the Archaic through the Hellenistic periods (ca. 750-30 BC), scientific progress was an important agent in the development of water management in some ancient Greek cities including institutional and regulations issues. In most cities, it seems not to have been a prerequisite in relation to basic agricultural or household requirements. Previous studies suggest that judicial insight rather than practical knowledge of basic water management became a vital part of how socio-political and religious organizations dealing with water management functioned. The evidence indicate an interest in institutional matters, but in some instances also in the day-to-day handling of water issues. -

Inquiry Based Learning for Civic Ecology

Proceedings of the International Conference Daylighting Rivers: Inquiry Based Learning for Civic Ecology Florence 1-2 December 2020 Edited by Ugolini F. & Pearlmutter D. Cover photo: © Múdu Ugolini F., Pearlmutter D., 2020. Proceedings of the International Conference “Daylighting Rivers: Inquiry Based Learning for Civic Ecology”. Florence, 1-2 December 2020. © Cnr Edizioni, 2020 P.le Aldo Moro 7 00185 Roma ISBN 978 88 8080 424 6 DOI: 10.26388/IBE201201 Proceedings of the International Conference Daylighting Rivers: Inquiry Based Learning for Civic Ecology Online Conference 1-2 December 2020 Edited by Ugolini F. & Pearlmutter D. Organizers: The European Commission’s support for the production of this publication does not constitute endorsement of the contents which reflect the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. Preface This conference represents the final event of the Daylighting Rivers project, which has engaged secondary school students in inquiry-based and interdisciplinary learning focused on land and river use and transformations, with an emphasis on the ways in which urban growth impacts local river ecosystems. Three pilot schools in Europe successfully implemented this approach, involving more than 200 students in the application of learning units developed within the project to investigate different aspects of their local rivers, from biodiversity to environmental threats. In its second phase, the project engaged additional schools who overcame the obstacles of time and COVID-19 to participate in the International Competition “Schools in Action for Daylighting Rivers”. This competition has brought together groups of students eager to discover the rivers of their local area, inspiring global action for sustainability. -

Information Document

TITLE OF THE TENDER: LINE 4 – SECTION A’ “ALSOS VEIKOY – GOUDI” RFP-308/17 INFORMATION DOCUMENT LINE 4 – SECTION A’ “ALSOS VEIKOU - GOUDI” RFP-308/17 INFORMATION DOCUMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 2 2 Transportation planning of Line 4 ................................................................................ 2 3 Line 4 – Section A’ “Alsos Veikou – Goudi”, Basic Characteristics .......................... 3 4 Scope of the Project ...................................................................................................... 4 4.1 Civil Works ................................................................................................................ 4 4.2 Electromechanical and Railway Systems related Works ....................................... 6 4.3 Establishment of the Project’s Log ......................................................................... 8 5 Description of the Project ............................................................................................. 8 5.1 Location and brief description of the Stations ....................................................... 8 5.2 Train Stabling, Cleaning and Maintenance Facilities in Katehaki Area ............... 10 5.3 Train Stabling, Cleaning and Maintenance Facilities in Veikou Area .................. 10 5.4 Tunnels .................................................................................................................... 10 -

Ancient Centres of Globalization

To preserve our common cultural ARCHAEOLOGY heritage, we need WORLDWIDE 1 t 2015 your support. Magazine of the German Archaeological Institute T WG Archaeology Worldwide – volume three – Berlin, May 2015 – DAI – 2015 May Berlin, three– volume Archaeology – Worldwide Here are details on how to help: WWW.TWGES.DE Gesellschaft der Freunde des The Fatimid Cemetery of Aswan / Photos: DAI Cairo The Fatimid Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Theodor Wiegand Gesellschaft e.V. With about 500 private graves and 50 mausoleums, the early Islamic “Fatimid Cem- Wissenschaftszentrum Bonn etery” of Aswan is one of the biggest Islamic cemeteries in Egypt. It was built between Ahrstraße 45, 53175 Bonn the 7th and 11th century and was first documented in the 1920s by the Italian archi- tect Hugo Monneret de Villard. Dorothea Lange The Fatimid Cemetery, which contains many items from Pharaonic times and antiq- Tel.: +49 228 30 22 64 uity, is located in an area that once served as a quarry – its rose granite was sought Fax: +49 228 30 22 70 after throughout the ancient world. The inscriptions, petroglyphs and grave stelae are [email protected] of great archaeological significance. However, the mortuary structures, largely built of mud-brick and over a thousand years old, had fallen into disrepair. In 2006, the Ger- Theodor Wiegand Gesellschaft man Archaeological Institute in association with the Technical University of Berlin consequently launched a project that was successfully concluded this year. The large Deutsche Bank AG, Essen TITLE STORY IBAN DE20 3607 0050 0247 1944 00 mausoleums and many private graves were investigated and documented. In all, nine BIC DEUTDEDEXXX mausoleums were structurally consolidated and approx. -

Church, Society, and the Sacred in Early Christian Greece

CHURCH, SOCIETY, AND THE SACRED IN EARLY CHRISTIAN GREECE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By William R. Caraher, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2003 Dissertation Committee: Approved By Professor Timothy E. Gregory, Adviser Professor James Morganstern Professor Barbara Hanawalt _____________________ Adviser Professor Nathan Rosenstein Department of History ABSTRACT This dissertation proposes a social analysis of the Early Christian basilicas (4th-6th century) of Southern and Central Greece, predominantly those in the Late Roman province of Achaia. After an introduction which places the dissertation in the broader context of the study of Late Antique Greece, the second chapter argues that church construction played an important role in the process of religions change in Late Antiquity. The third chapter examines Christian ritual, architecture, and cosmology to show that churches in Greece depended upon and reacted to existing phenomena that served to promote hierarchy and shape power structures in Late Roman society. Chapter four emphasizes social messages communicated through the motifs present in the numerous mosaic pavements which commonly adorned Early Christian buildings in Greece. The final chapter demonstrates that the epigraphy likewise presented massages that communicated social expectations drawn from both an elite and Christian discourse. Moreover they provide valuable information for the individuals who participated in the processes of church construction. After a brief conclusion, two catalogues present bibliographic citations for the inscriptions and architecture referred to in the text. The primary goal of this dissertation is to integrate the study of ritual, architecture, and social history and to demonstrate how Early Christian architecture played an important role in affecting social change during Late Antiquity. -

List of Rivers of Greece

Sl. No River Name Location (City / Region ) Draining Into Region Location 1 Aoos/Vjosë Near Novoselë, Albania Adriatic Sea 2 Drino In Tepelenë, Albania Adriatic Sea 3 Sarantaporos Near Çarshovë, Albania Adriatic Sea 4 Voidomatis Near Konitsa Adriatic Sea 5 Pavla/Pavllë Near Vrinë, Albania Ionian Sea Epirus & Central Greece 6 Thyamis Near Igoumenitsa Ionian Sea Epirus & Central Greece 7 Tyria Near Vrosina Ionian Sea Epirus & Central Greece 8 Acheron Near Parga Ionian Sea Epirus & Central Greece 9 Louros Near Preveza Ionian Sea Epirus & Central Greece 10 Arachthos In Kommeno Ionian Sea Epirus & Central Greece 11 Acheloos Near Astakos Ionian Sea Epirus & Central Greece 12 Megdovas Near Fragkista Ionian Sea Epirus & Central Greece 13 Agrafiotis Near Fragkista Ionian Sea Epirus & Central Greece 14 Granitsiotis Near Granitsa Ionian Sea Epirus & Central Greece 15 Evinos Near Missolonghi Ionian Sea Epirus & Central Greece 16 Mornos Near Nafpaktos Ionian Sea Epirus & Central Greece 17 Pleistos Near Kirra Ionian Sea Epirus & Central Greece 18 Elissonas In Dimini Ionian Sea Peloponnese 19 Fonissa Near Xylokastro Ionian Sea Peloponnese 20 Zacholitikos In Derveni Ionian Sea Peloponnese 21 Krios In Aigeira Ionian Sea Peloponnese 22 Krathis Near Akrata Ionian Sea Peloponnese 23 Vouraikos Near Diakopto Ionian Sea Peloponnese 24 Selinountas Near Aigio Ionian Sea Peloponnese 25 Volinaios In Psathopyrgos Ionian Sea Peloponnese 26 Charadros In Patras Ionian Sea Peloponnese 27 Glafkos In Patras Ionian Sea Peloponnese 28 Peiros In Dymi Ionian Sea Peloponnese