Zennor Churchway Craig Weatherhill.Pub

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

176 Exchange (Penzance), Rail Ale Trail, 114 43, 49 Seven Stones pub (St Index Falmouth Art Gallery, Martin’s), 168 Index 101–102 Skinner’s Brewery A Foundry Gallery (Truro), 138 Abbey Gardens (Tresco), 167 (St Ives), 48 Barton Farm Museum Accommodations, 7, 167 Gallery Tresco (New (Lostwithiel), 149 in Bodmin, 95 Gimsby), 167 Beaches, 66–71, 159, 160, on Bryher, 168 Goldfish (Penzance), 49 164, 166, 167 in Bude, 98–99 Great Atlantic Gallery Beacon Farm, 81 in Falmouth, 102, 103 (St Just), 45 Beady Pool (St Agnes), 168 in Fowey, 106, 107 Hayle Gallery, 48 Bedruthan Steps, 15, 122 helpful websites, 25 Leach Pottery, 47, 49 Betjeman, Sir John, 77, 109, in Launceston, 110–111 Little Picture Gallery 118, 147 in Looe, 115 (Mousehole), 43 Bicycling, 74–75 in Lostwithiel, 119 Market House Gallery Camel Trail, 3, 15, 74, in Newquay, 122–123 (Marazion), 48 84–85, 93, 94, 126 in Padstow, 126 Newlyn Art Gallery, Cardinham Woods in Penzance, 130–131 43, 49 (Bodmin), 94 in St Ives, 135–136 Out of the Blue (Maraz- Clay Trails, 75 self-catering, 25 ion), 48 Coast-to-Coast Trail, in Truro, 139–140 Over the Moon Gallery 86–87, 138 Active-8 (Liskeard), 90 (St Just), 45 Cornish Way, 75 Airports, 165, 173 Pendeen Pottery & Gal- Mineral Tramways Amusement parks, 36–37 lery (Pendeen), 46 Coast-to-Coast, 74 Ancient Cornwall, 50–55 Penlee House Gallery & National Cycle Route, 75 Animal parks and Museum (Penzance), rentals, 75, 85, 87, sanctuaries 11, 43, 49, 129 165, 173 Cornwall Wildlife Trust, Round House & Capstan tours, 84–87 113 Gallery (Sennen Cove, Birding, -

Working with Local Farmers

October 2016 Ow lavurya gans tiogow Working with local farmers In July, about fifty farmers However, our local moors gathered at Landithy Hall in and downland do not always Madron to hear about some meet the requirements of of the ways in which the these national schemes. On Penwith Landscape farms where this is the case, Partnership scheme might we would like to focus on be able to help support getting on with practical work farming in Penwith. Many that may be required: helping thanks to all who came with the cost of bracken along and to the farmers spraying to open up areas and landowners who have ahead of grazing or of given their time since then mechanical scrub control to to help develop ideas. improve access; and many of these no longer play an active providing volunteer help to clear around There is a clear need for practical help role in farm business. The Partnership historic settlements and monuments by with the management and use of rough will be able to help farmers access hand. ground. Most Penwith farms have income from Countryside Stewardship Continued overleaf areas of wetland and heathland, but Higher Tier where this is possible. Events and meetings coming up Do you know about some of the historic features in your Parish? Woul d you like to get involved in surveying wildlife and heritage in your locality? Are you interested in hands-on practical work to help manage the environment? Or in helping to record and restore Cornish hedges? Please come along to a Parish meeting in your area: Tuesday 8th November at St Just Old Town Council (for those living in the Parishes of Sennen, St Levan, St Buryan, Sancreed, Paul and St Just); or Thursday 24th November at Landithy Hall, Madron (Towednack, Zennor, Madron, Morvah and Ludgvan) Both meetings from 6 - 8pm with refreshments This is your opportunity to chat to people involved in this exciting work and give us your ideas and suggestions. -

16A Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

16A bus time schedule & line map 16A Penzance View In Website Mode The 16A bus line (Penzance) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Penzance: 7:30 AM - 4:17 PM (2) St Ives: 8:08 AM - 5:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 16A bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 16A bus arriving. Direction: Penzance 16A bus Time Schedule 34 stops Penzance Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:30 AM - 4:17 PM Tesco, St Ives Tuesday 7:30 AM - 4:17 PM Cornish Arms, St Ives Trelyon Avenue, St. Ives Civil Parish Wednesday 7:30 AM - 4:17 PM St Ives Harbour Hotel, St Ives Thursday 7:30 AM - 4:17 PM Friday 7:30 AM - 4:17 PM Cinema, St Ives Chapel Street, St Ives Saturday 7:35 AM - 3:57 PM Stennack Surgery, St Ives Drillƒeld Lane, St Ives Opp St James Court, St Ives 16A bus Info Higher Stennack, St Ives Direction: Penzance Stops: 34 British Legion, St Ives Trip Duration: 60 min Line Summary: Tesco, St Ives, Cornish Arms, St Ives, Trenwith Bridge, St Ives St Ives Harbour Hotel, St Ives, Cinema, St Ives, Stennack Surgery, St Ives, Opp St James Court, St Higher Stennack, St Ives Ives, British Legion, St Ives, Trenwith Bridge, St Ives, Higher Stennack, St Ives, Leach Pottery, St Ives, Leach Pottery, St Ives Joannies Avenue, St Ives, Fernlee, Penbeagle, Higher Stennack, St. Ives Civil Parish Halsetown Inn, Halsetown, Penhalwyn Trekking Centre, Balnoon, Penderleath Common, Balnoon, Joannies Avenue, St Ives Towednack Turn, Trevalgan, Wicca Farm, Zennor, Joannies Avenue, St. -

201914Th-28Th September Programme of Events

A TWO WEEK CELEBRATION OF MUSIC AND THE ARTS IN ST IVES CORNWALL ST IVES SEPTEMBER FESTIVAL 201914th-28th September Programme of Events Visit our website for updates and online booking: www.stivesseptemberfestival.co.uk and follow us on facebook, twitter and instagram. Tickets & Information Unless otherwise stated, tickets are available from: St Ives School of Painting l www.stivesseptemberfestival.co.uk Outside Workshops l Cornwall Riviera Box Office: 01726 879500 For outside workshops we recommend l Visit St Ives Information Centre, St Ives Library, Gabriel Street, St Ives TR26 2LU you bring sturdy walking shoes (or Opening hours: Mon to Sat 9.30am-5pm, Sun 10am-3pm 01736 796297 trainers) and either warm waterproof l Tourist Offices in Penzance, Truro, St Mawes, St Austell, Bodmin, Launceston, clothing, sunhats and sun cream as Liskeard. appropriate. We meet at Porthmeor l Tickets on the door if available. Studios but a few landscape workshops are based at the Penwith Studio, Information Points accessed via a steep cobbled ramp. l Café Art, The Drill Hall, Royal Square, St Ives. Mon, Wed, Fri, Sat 10am-4pm - Tues, Thurs 10am-5pm, Sun 11am-4pm l Outside Mountain Warehouse, Fore Street, Sat 14th and 21st 10am-5pm Pre-Concert Suppers The 2019 Festival Raffle Café Art, The Drill Hall, Win Cheese and Chocolate. Prize is donated by ‘Cheese On Coast’ and ‘I Should Chapel Street, St IvesTR26 2LR Coco’. Raffle tickets can be bought at a number of venues, including The Guildhall Vegetarian hot meals served in an and Café Art during the Festival. The winner will be announced at the end of October. -

Ref: LCAA7509 Offers Around £595,000

Ref: LCAA7509 Offers around £595,000 Pit Pry, Zennor, St Ives, West Cornwall, TR26 3DA FREEHOLD A particularly attractive detached and extended granite fronted house set in an elevated position enjoying lovely views over the acutely desirable village of Zennor and to the sea beyond. Set in good sized and spacious gardens with a detached artist’s studio enjoying the views. 3/4 bedroomed characterful accommodation in lovely mature gardens make this an ideal holiday or main coastal home. 2 Ref: LCAA7509 SUMMARY OF ACCOMMODATION Ground Floor: porch, living room, kitchen/breakfast room, study/bedroom 4, bathroom. First Floor: master bedroom with en-suite and sun deck, 2 further guest bedrooms. Outside: mature coastal gardens terraced with garden shed, detached artist’s studio. Off-road parking for 2 vehicles. DESCRIPTION Pit Pry is a particularly attractive, granite fronted house, sympathetically extended and set in an elevated position taking in some lovely views. There are two entrances to the house, both to the front, either via the pitched roofed half glazed porch or through a stable door directly into the kitchen. The main reception room is lovely with a super fireplace housing a woodburning stove, beamed ceiling and tiled floor. There are two windows and double doors to the front with a further side window, all of which enjoy some outlook and views. The dual aspect kitchen is refitted with light fronted units under timber worksurfaces. The room is dual aspect and with a stable door leading directly into the front lawned garden. 3 Ref: LCAA7509 From the living room there is a rear hallway with cupboard space and access to the study/bedroom 4 to one side with a modern refitted bathroom suite to the other. -

Dolly Pentreath

Dolly Pentreath Dorothy Pentreath (16 May 1692 – 26 December rather better cottages just opposite it he had found two 1777), known as Dolly, was a speaker of the Cornish other women, some ten or twelve years younger than Pen- language. She is the most well-known of the last flu- treath, who could not speak Cornish readily, but who un- ent, native speakers of the Cornish language, prior to derstood it. Five years later, Pentreath was said to be 87 its revival in 1904, from which time some children have years old and at the time her hut was “poor and main- been raised as bilingual native speakers of revived Cor- tained mostly by the parish, and partly by fortune telling nish. Although it is sometimes claimed she was the last and gabbling Cornish.”[3] monolingual speaker of the language – the last person In the last years of her life, Pentreath became a lo- who spoke only Cornish, and not English – her own ac- cal celebrity for her knowledge of Cornish.[5] Around count as recorded by Daines Barrington contradicts this. 1777, she was painted by John Opie (1761–1807), and in 1781 an engraving of her after Robert Scaddan was published.[1] 1 Biography In 1797, a Mousehole fisherman told Richard Polwhele (1760–1838) that William Bodinar “used to talk with her 1.1 Early life for hours together in Cornish; that their conversation was understood by scarcely any one of the place; that both Baptised on 16 May 1692,[1] Pentreath was probably the Dolly and himself could talk in English.”[6] second of the six children of Nicholas Pentreath, a fish- Pentreath has passed into legend for cursing people in erman, by his second wife, Jone Pentreath.[2] She later a long stream of fierce Cornish whenever she became claimed that she could not speak a word of English un- angry.[7] Her death is seen as marking the death of Cor- til the age of 20. -

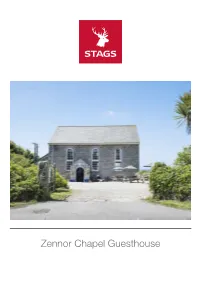

Zennor Chapel Guesthouse Zennor Chapel Guesthouse Zennor, St Ives, Cornwall

Zennor Chapel Guesthouse Zennor Chapel Guesthouse Zennor, St Ives, Cornwall, SITUATION Cornwall. The cafe currently has 30 Around five miles south-west of St. Ives, covers whilst the en-suite bedrooms Zennor is situated in an Area of comprise two doubles, two family rooms Outstanding Natural Beauty only half a and a further bedroom with a pair of mile from the majestic north Cornish bunk beds, sleeping 16 in total. coast. It is considered that further scope exists Famed for the medieval carving of a to extend the business perhaps with a St Ives - 5 miles Sennen - 15 miles mermaid inside the Parish Church and restaurant serving in the evening or even Penzance - 7 miles Coast - 0.5 mile once the home of D. H. Lawrence, the weddings (subject to obtaining all village comprises a cluster of traditional necessary consents and licences). granite buildings including the historic THE GROUNDS Tinners Arms whilst the award winning Gurnards Head Inn is around two miles There is car parking in a granite chipped distant. forecourt area to the front whilst to the rear is a lawned garden which is stream Tourism is the principal industry in the bordered. area and the landscape is a walkers THE BUSINESS paradise. Much of the surrounding land The cafe currently opens seven days a A rare chance to acquire is in the ownership of The National Trust week between 9am and 5pm from and from the village there is easy access Easter to the end of October. The an attractive lifestyle onto the scenic Southwest Coast Path enterprise is run by the Vendors together and Zennor Head. -

Pendeen with Morvah 2020

https://pendeenoutreach.blogspot.co.uk/ IMPORTANT 15th July for August and NEW is 12th August for September Contributions can still be on paper to be left at Pendeen Post Office and must be received by the closing date. 500 paper copies will be printed and available in the usual outlets in Pendeen and St Just Pendeen with Morvah 2020 Page 1 Church of Pendeen with Morvah Parish Priest in Charge Rev Karsten Wedgewood Ermelo, Pendeen TR19 7SQ Tel: 788829 Email: [email protected] Churchwardens Howard Blundy: Tel: 788107 Mob :07814 715452 Mrs Jane Colliver Tel: 787440 Deputy Churchwardens Mrs Helen Hichens: Tel: 788309 Mrs Mary Kingdon: Tel: 788588 Malcolm Earley Tel: 788636 Verger Ken Patrick: Tel: 787677 Mob: 07773340489 Church Treasurer Bryan Cuddy: Tel: 811168 PCC Secretary Mrs Marna Blundy: Tel: 788107 IMPORTANT last date Wednesday 15th July for August 2020 INFORMATION TO ALL CONTRIBUTORS: The latest time for contributions to be accepted is 4pm on the closing date whether emailed to Rachel Ewer, Fiona Flindall or Jackie Packer OR deposited at Pendeen Post Office. You MUST include a CONTACT NAME AND PHONE NUMBER (plus an address unless we already have that information) with each contribution. The Magazine Committee is very proud of Outreach and the quality is due in particular to our contributors. We are very grateful to them. If another publication wishes to reprint any item from Outreach, permission must be obtained from the Editor (Rachel Ewer). If she is not available then please contact Jackie Packer. Permission will usually be granted, but only on condition that any such item must be reprinted in its entirety and attributed. -

St Ives to Penzance Penzance to St Ives

16 St Ives to Penzance via Nancledra | Gulval | Penzance Mondays to Saturdays except bank holidays Carbis Bay Tesco 0730 0730 0840 0940 1040 1140 1240 1340 1340 1440 1521 1540 1640 1740 1840 St Ives School 1525 St Ives Cinema 0736 0736 0846 0946 1046 1146 1246 1346 1346 1446 1531 1546 1646 1746 1846 Penbeagle Porthia Close 0744 0744 0854 0954 1054 1154 1254 1354 1354 1454 1539 1554 1654 1754 1854 Penbeagle Fire Station 0746 0746 0856 0956 1056 1156 1256 1356 1356 1456 1541 1556 1656 1756 1856 Halsetown Inn 0749 0749 0859 0959 1059 1159 1259 1359 1359 1459 1544 1559 1659 1759 1859 Nancledra Telephone Box 0754 0754 0904 1004 1104 1204 1304 1404 1404 1504 1549 1604 1704 1804 1904 44 Castle Gate Lay By 0759 0759 0909 1009 1109 1209 1309 1409 1409 1509 1554 1609 1709 1809 1909 Ludgvan Telephone Box 0803 0803 0913 1013 1113 1213 1313 1413 1413 1513 1558 1613 1713 1813 1913 Gulval School Lane 0809 0809 0919 1019 1119 1219 1319 1419 1419 1519 1604 1619 1719 1819 1919 Gulval Green Lane Hill 0812 0812 0922 1022 1122 1222 1322 1422 1422 1522 1607 1622 1722 1822 1922 Mounts Bay School 0825 Humphry Davy School 0830 Eastern Green Sainsbury car park 0816 0926 1026 1126 1226 1326 1426 1426 1526 1611 1626 1726 1826 1926 Penzance Bus Station [D] arr 0824 0840 0934 1034 1134 1234 1334 1434 1434 1534 1619 1634 1734 1834 1934 Penzance Bus Station [D] dep 0845 0845 0940 1040 1140 1240 1340 1440 1440 1540 1540 1640 1640 1740 1840 Green Market 0848 0848 0943 1043 1143 1243 1343 1443 1443 1543 1543 1643 1643 1743 1843 Treneere Pendennis Road 0950 1050 1150 1250 -

Zennor Parish Council

Zennor Parish Council Chairperson: Cllr J F Brookes, Tredour, Zennor, St Ives, TR26 3DA. 01736 799492 Clerk: Mickey Downing, 9 Lower Gurnick Road, Newlyn, Penzance, TR18 5QN. 01736 366556 Minutes of Meeting Monday 7th March 2016 Present: Cllrs Jon Brookes (Chair), Lottie Millard, Nick Lambert Also Attending: Mickey Downing (Clerk) Members of the public: Cllr Kevin Hughes (TPC Chair); Milly Ainsley Apologies: Cllrs Sam Nankervis (Vice Chair), Sandy Martin, Nicky Monies, Roy Mann (Cornwall Council) 1. Welcome and Apologies As above Congratulations to Cllr Nicky Monies on the recent birth of his daughter Get Well Soon to Cllr Sandy Martin whose presents has been missed of late due to illness 2. Minutes 9th February 2016 Minutes signed as read, correct and agreed. 3. Matters Arising The Chair, Cllr Brookes, requested item 17 be bought forward regarding to co-opting of a new councillor. He proposed Milly Ainsley, this being seconded by Cllr Lambert and agreed unanimously by those present. Milly accepted the position being welcomed as Cllr Ainsley, a valued part of ZPC. 4. Declaration of Interest Cllr Brookes declared an interest regarding parish path cutting. 5. Public Participation Cllr K Hughes (TPC Chair) 6. Parish Council regulations & procedures Copies of all respective documentation be sent to Milly Ainsley (clerk) 7. Towednack Parish Council Cllr Jon Brookes has now been welcomed by the TPC filing the long standing councillor vacancy whilst stating his willingness to step down should a more local person show interest. Chair’s Cllrs Brookes (ZPC) and Hughes (TPC) both made positive comments regarding the ‘Flood training/scheme’. -

PORTHZENNOR COVE and Veor Cove

North Coast – West Cornwall PORTHZENNOR COVE and Veor Cove Two coves a short distance from the village of Zennor set in the wild granitic coastline west of St.Ives and surrounded by an ancient landscape full of mystery and Cornish legends. Porthzennor Cove is tucked in to the east of Zennor Head and despite facing north can often be relatively sheltered. Veor Cove is to the west Porthzennor access path Veor Cove access path of Zennor Head (beyond the inaccessible Pendour Cove). Both Coves can be reached from the Coast Path which after some 400m joins up with the Coast Path; turn left and about 180m on the right there is a path down to the beach. Normally both Coves have fine white sand from high water down to low water in the summer months which usually disappears after winter storms. There is no safety equipment at either Cove. It is not advisable to swim accept on a rising high tide and then only when Porthzennor Cove at low water & devoid of sand in early summer conditions are favourable. They are not regarded as surfing beaches even though there can be good surf. There are some rock pools. Snorkelling can be TR26 3BY - Take the B3306 coast road interesting at high water in both coves but conditions from the St.Ives to St.Just and some 7kms west of are rarely favourable. St.Ives there is the village (little more than a hamlet) of Zennor with its church which is so prominent in the landscape. Turn off the main road and there is a small There are no restrictions on car park (capacity 130 cars) between the Museum and dogs. -

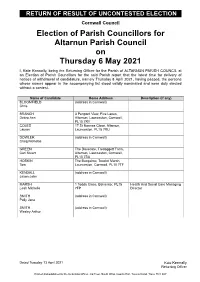

Election of Parish Councillors for Altarnun Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021

RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Cornwall Council Election of Parish Councillors for Altarnun Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Kate Kennally, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 8 April 2021, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BLOOMFIELD (address in Cornwall) Chris BRANCH 3 Penpont View, Five Lanes, Debra Ann Altarnun, Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7RY COLES 17 St Nonnas Close, Altarnun, Lauren Launceston, PL15 7RU DOWLER (address in Cornwall) Craig Nicholas GREEN The Dovecote, Tredoggett Farm, Carl Stuart Altarnun, Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7SA HOSKIN The Bungalow, Trewint Marsh, Tom Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7TF KENDALL (address in Cornwall) Jason John MARSH 1 Todda Close, Bolventor, PL15 Health And Social Care Managing Leah Michelle 7FP Director SMITH (address in Cornwall) Polly Jane SMITH (address in Cornwall) Wesley Arthur Dated Tuesday 13 April 2021 Kate Kennally Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, 3rd Floor, South Wing, County Hall, Treyew Road, Truro, TR1 3AY RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Cornwall Council Election of Parish Councillors for Antony Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Kate Kennally, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of ANTONY PARISH COUNCIL at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 8 April 2021, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest.