Chronic Suppurative Otitis Media: Burden of Illness and Management Options Or Bathing Also Leads to Intermittent and Unpleasant Discharges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

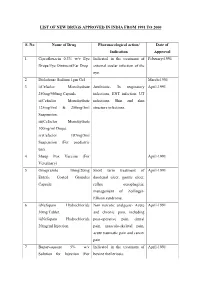

List of New Drugs Approved in India from 1991 to 2000

LIST OF NEW DRUGS APPROVED IN INDIA FROM 1991 TO 2000 S. No Name of Drug Pharmacological action/ Date of Indication Approval 1 Ciprofloxacin 0.3% w/v Eye Indicated in the treatment of February-1991 Drops/Eye Ointment/Ear Drop external ocular infection of the eye. 2 Diclofenac Sodium 1gm Gel March-1991 3 i)Cefaclor Monohydrate Antibiotic- In respiratory April-1991 250mg/500mg Capsule. infections, ENT infection, UT ii)Cefaclor Monohydrate infections, Skin and skin 125mg/5ml & 250mg/5ml structure infections. Suspension. iii)Cefaclor Monohydrate 100mg/ml Drops. iv)Cefaclor 187mg/5ml Suspension (For paediatric use). 4 Sheep Pox Vaccine (For April-1991 Veterinary) 5 Omeprazole 10mg/20mg Short term treatment of April-1991 Enteric Coated Granules duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, Capsule reflux oesophagitis, management of Zollinger- Ellison syndrome. 6 i)Nefopam Hydrochloride Non narcotic analgesic- Acute April-1991 30mg Tablet. and chronic pain, including ii)Nefopam Hydrochloride post-operative pain, dental 20mg/ml Injection. pain, musculo-skeletal pain, acute traumatic pain and cancer pain. 7 Buparvaquone 5% w/v Indicated in the treatment of April-1991 Solution for Injection (For bovine theileriosis. Veterinary) 8 i)Kitotifen Fumerate 1mg Anti asthmatic drug- Indicated May-1991 Tablet in prophylactic treatment of ii)Kitotifen Fumerate Syrup bronchial asthma, symptomatic iii)Ketotifen Fumerate Nasal improvement of allergic Drops conditions including rhinitis and conjunctivitis. 9 i)Pefloxacin Mesylate Antibacterial- In the treatment May-1991 Dihydrate 400mg Film Coated of severe infection in adults Tablet caused by sensitive ii)Pefloxacin Mesylate microorganism (gram -ve Dihydrate 400mg/5ml Injection pathogens and staphylococci). iii)Pefloxacin Mesylate Dihydrate 400mg I.V Bottles of 100ml/200ml 10 Ofloxacin 100mg/50ml & Indicated in RTI, UTI, May-1991 200mg/100ml vial Infusion gynaecological infection, skin/soft lesion infection. -

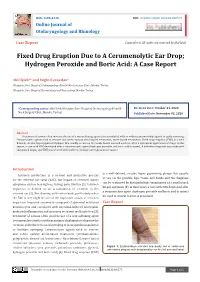

Fixed Drug Eruption Due to a Cerumenolytic Ear Drop; Hydrogen Peroxide and Boric Acid: a Case Report

ISSN: 2688-8238 DOI: 10.33552/OJOR.2020.04.000577 Online Journal of Otolaryngology and Rhinology Case Report Copyright © All rights are reserved by Akif İşlek Fixed Drug Eruption Due to A Cerumenolytic Ear Drop; Hydrogen Peroxide and Boric Acid: A Case Report Akif İşlek1* and Engin Karaaslan2 1Nusaybin State Hospital, Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery Clinic, Mardin, Turkey 2Nusaybin State Hospital, Dermatology and Venereology, Mardin, Turkey *Corresponding author: Received Date: October 24, 2020 Published Date: November 03, 2020 Akif İşlek, Nusaybin State Hospital, Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery Clinic, Mardin, Turkey. Abstract Treatment of earwax often involves the use of a wax softening agent (cerumenolytic) with or without antimicrobial agents to easily removing. Cerumenolytic agents used to remove and soften earwax areoil-based treatments, water-based treatments. Fixed drug eruption (FDE) is a well- defined, circular, hyperpigmented plaque that usually occurs on the trunk, hands mucosal surfaces, after a systemical application of drugs. In this report, a case with FDE developed after a cerumenolytic agent (hydrogen peroxide and boric acid in water). A definitive diagnosis was made with skin punch biopsy and FDE was treated with oral levocetirizine and topical mometasone. Introduction is a well-defined, circular, hyper pigmenting plaque that usually Cerumen production is a normal and protective process occurs on the genitals, lips, trunk, and hands and the diagnosis for the external ear canal (EAC), but impact of cerumen causes can be confirmed by histopathologic examination of a small punch symptoms such as hearing loss, itching, pain, tinnitus [1]. Cerumen biopsy specimen [5]. In this report, a case with FDE developed after impaction is defined as an accumulation of cerumen in the a cerumenolytic agent (hydrogen peroxide and boric acid in water) external ear [2]. -

Acute Otitis Media, Acute Bacterial Sinusitis, and Acute Bacterial Rhinosinusitis

Acute Otitis Media, Acute Bacterial Sinusitis, and Acute Bacterial Rhinosinusitis This guideline, developed by Larry Simmons, MD, in collaboration with the ANGELS team, on October 3, 2013, is a significantly revised version of the Recurrent Otitis Media guideline by Bryan Burke, MD, and includes the most recent information for acute otitis media, acute bacterial sinusitis, and acute bacterial rhinosinusitis. Last reviewed by Larry Simmons, MD on July 5, 2016. Preface As the risk factors for the development of acute otitis media (AOM) and acute bacterial sinusitis (ABS)/ acute bacterial rhinosinusitis (ABRS) are similar, the bacterial pathogens are essentially the same for both AOM and ABS/ABRS, and since the antimicrobial treatments are similar, the following guideline is based, unless otherwise referenced, on recently published evidenced-based guidelines by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) for AOM,1,2 and by the Infectious Diseases Society of 3 America (IDSA) for ABRS. This guideline applies to children 6 months to 12 years of age and otherwise healthy children without pressure equalizer (PE) tubes, immune deficiencies, cochlear implants, or anatomic abnormalities including cleft palate, craniofacial anomalies, and Down syndrome. However, the IDSA ABRS guideline includes recommendations for children and adult patients. Key Points Acute otitis media (AOM) is characterized by a bulging tympanic membrane (TM) + middle-ear effusion. Antibiotic treatment is indicated in children ≥6 months of age with severe AOM, children 6-23 months of age with mild signs/symptoms of bilateral AOM. In children 6-23 months of age with non-severe unilateral AOM, and in children ≥24 months of age with bilateral or unilateral 1 AOM who have mild pain and low fever <39°C/102.2°F, either antibiotic treatment or observation is appropriate. -

Objective Measures of Ototoxicity

The following article appeared in the September 2005 issue (Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 10-16) of the Division 6 publication Perspectives on Hearing and Hearing Disorders: Research and Diagnostics. To learn more about Division 6, contact the ASHA Action Center at 1-800-498-2071 or visit the division’s Web page at www.asha.org/about/membership-certification/divs/div_6.htm. Objective Measures of Ototoxicity Elizabeth Leigh-Paffenroth Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development Service, National Center for Rehabilitative Auditory Research, VA Medical Center Portland, OR Department of Otolaryngology, Oregon Health & Science University Portland, OR Kelly M. Reavis, Jane S. Gordon, Kathleen T. Dunckley Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development Service, National Center for Rehabilitative Auditory Research, VA Medical Center Portland, OR Stephen A. Fausti and Dawn Konrad-Martin Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development Service, National Center for Rehabilitative Auditory Research, VA Medical Center Portland, OR Department of Otolaryngology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR A leading cause of preventable sensorineural hear- of patients who are unable to provide reliable re- ing loss is therapeutic treatment with medications that sponses; subsequently, many of these patients do not are toxic to inner ear tissues, including certain drugs receive monitoring for ototoxic-induced changes in used to fight cancer and life-threatening infectious dis- their hearing. The development of objective measures eases. Ototoxic-induced hearing loss typically begins that do not require patient cooperation is necessary to in the high frequencies and progresses to lower fre- monitor all patients receiving ototoxic drugs. quencies as drug administration continues (Campbell Two objective measures offer promise in their abil- & Durrant, 1993; Campbell et al., 2003; Macdonald, ity to detect and to monitor hearing changes caused by Harrison, Wake, Bliss, & Macdonald, 1994). -

SINUSITIS AS a CAUSE of TONSILLITIS. by BEDFORD RUSSELL, F.R.C.S., Surgeon-In-Charge, Throat Departmentt, St

Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.9.89.80 on 1 March 1933. Downloaded from 80 POST-GRADUATE MEDICAL JOURNAL March, 1933 Plastic Surgery: A short course of lecture-demonstrations is being arranged, to be given at the Hammersmith Hospitar, by Sir Harold Gillies, Mr. MacIndoe and Mr. Kilner. Details will be circulated shortly. Technique of Operations: A series of demonstrations is being arranged. Details will be circulated shortly. Demonstrations in (Advanced) Medicine and Surgeryi A series of weekly demonstrations is being arranged. Details will be circulated shortly. A Guide Book, giving details of how to reach the various London Hospitals by tube, tram, or bus, can be obtained from the Fellowship. Price 6d. (Members and Associates, 3d.). SINUSITIS AS A CAUSE OF TONSILLITIS. BY BEDFORD RUSSELL, F.R.C.S., Surgeon-in-Charge, Throat Departmentt, St. Bart's Hospital. ALTHOUGH the existence of sinus-infection has long since been recognized, medical men whose work lies chiefly in the treatment of disease in the nose, throat and ear are frequently struck with the number of cases of sinusitis which have escaped recognition,copyright. even in the presence of symptoms and signs which should have given rise at least to suspicion of such disease. The explanation of the failure to recognize any but the most mlianifest cases of sinusitis lies, 1 think, in the extreme youth of this branch of medicine; for although operations upon the nose were undoubtedly performed thousands of years ago, it was not uintil the adoption of cocaine about forty years ago that it was even to examine the nasal cavities really critically. -

Chronic Otitis Media: Histopathological Changes a Post Mortem Study on Temporal Bones

European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 1999; 3: 175-178 Chronic otitis media: histopathological changes A post mortem study on temporal bones F. SALVINELLI, M. TRIVELLI, F. GRECO, F.H. LINTHICUM JR* Institute of Otolaryngology, “Campus Bio-Medico” University - Rome (Italy) *Department of Histopathology, “House Ear Institute” - Los Angeles, CA (USA) Abstract. – The temporal bones of 4 Materials and Methods deceased individuals, with concomitant chronic otitis media are studied. The various histopathological changes in the middle ear We have studied the histopathological cleft are examined: suppuration, polyps, changes in temporal bones of 4 deceased in- granulation tissue. The possibilities of spon- dividuals, with concomitant chronic OM. taneous healing of a perforated TM and the These patients were donors and agreed indications of surgical treatment are dis- during their life to donate post mortem their cussed. temporal bones to the House Ear Institute as Key Words: a contribution to a better knowledge of tem- Temporal bone, Middle ear, Infection, Chronic in- poral bone diseases. flammation, Metaplasia, Complications. We have removed the temporal bones in our usual way9. Introduction Results Otitis media (OM) is an infection localized Clinical features in the middle ear: mastoid, middle ear cavity, The inflammation, while often indolent, eustachian tube. The classification of OM in- may at times give rise to serious complica- cludes: tions and even cause death. The hearing loss that is a constant concomitant also con- tributes to the immense socio-economic problem. Chronic OM sometimes, but not al- • OM with effusion1-3, without perforation ways, follows an attack of the acute disease. of the tympanic membrane (TM)4-6, due The major feature is discharge from the mid- to an increase of fluid in the middle ear dle ear. -

Differentiated from the Rare Congenital Lues. Catarrhal Pharyngitis Produces Attacks of Hacking Cough with Frothy Mucus Appearing in the Mouth and on the Lips

Sir,-Your editorial in the February Research Newsletter has asked for sug- gestions on the classification and elucidation of minor maladies seen in general practice. I would like to recall the catarrhal diathesis of the older physicians. Perhaps it should be called a catarrhal state. It is extremely common especially in under fives and over fifties. It is conceived as an imperfect state of health or an incomplete defence against infection. Indeed, saprophytic organisms are encouraged to become virulent and inflammatory in the milieu of catarrh. In the newly born it is manifested as a sticky eye and a nasal snuffle which must be differentiated from the rare congenital lues. Catarrhal pharyngitis produces attacks of hacking cough with frothy mucus appearing in the mouth and on the lips. Catarrhal gastritis causes anorexia and irregular vomiting of curdy milk, sour fluid and mucus. Catarrhal bronchitis requires no description except to state that in its non-toxic afebrile form it can be associated with bronchospasm or bronchial relaxation. Deeper still within the young baby is the manifestation of catarrh called infantile gastro-enteritis which is a disease of uncertain etiology. At about four or five the child with the catarrhal diathesis develops tonsillar and adenoidal hypertrophy and hyperaemia, catarrhal otitis media (no pus formation), sinusitis and more active bronchitis with fever and secondary infections. Between seven and ten seems to be the favourite age for short attacks of mucous colitis. I have also seen two cases which clinicallv resembled ulcerative colitis but were of short duration. Stool cultures were negative for any pathogens and the disease occurred in isolated instances when no dysentery was observed in the vicinity. -

Inner Ear Infection (Otitis Interna) in Dogs

Hurricane Harvey Client Education Kit Inner Ear Infection (Otitis Interna) in Dogs My dog has just been diagnosed with an inner ear infection. What is this? Inflammation of the inner ear is called otitis interna, and it is most often caused by an infection. The infectious agent is most commonly bacterial, although yeast and fungus can also be implicated in an inner ear infection. If your dog has ear mites in the external ear canal, this can ultimately cause a problem in the inner ear and pose a greater risk for a bacterial infection. Similarly, inner ear infections may develop if disease exists in one ear canal or when a benign polyp is growing from the middle ear. A foreign object, such as grass seed, may also set the stage for bacterial infection in the inner ear. Are some dogs more susceptible to inner ear infection? Dogs with long, heavy ears seem to be predisposed to chronic ear infections that ultimately lead to otitis interna. Spaniel breeds, such as the Cocker spaniel, and hound breeds, such as the bloodhound and basset hound, are the most commonly affected breeds. Regardless of breed, any dog with a chronic ear infection that is difficult to control may develop otitis interna if the eardrum (tympanic membrane) is damaged as it allows bacteria to migrate down into the inner ear. "Dogs with long, heavy ears seem to bepredisposed to chronic ear infections that ultimately lead to otitis interna." Excessively vigorous cleaning of an infected external ear canal can sometimes cause otitis interna. Some ear cleansers are irritating to the middle and inner ear and can cause signs of otitis interna if the eardrum is damaged and allows some of the solution to penetrate too deeply. -

Rate of Concurrent Otitis Media in Upper Respiratory Tract Infections with Specific Viruses

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Rate of Concurrent Otitis Media in Upper Respiratory Tract Infections With Specific Viruses Cuneyt M. Alper, MD; Birgit Winther, MD, PhD; Ellen M. Mandel, MD; J. Owen Hendley, MD; William J. Doyle, PhD Objective: To estimate the coincidence of new otitis me- Results: A total of 176 children (81%) had isolated PCR dia (OM) for first nasopharyngeal detections of the more detection of at least 1 virus. The OM coincidence rates common viruses by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). were 62 of 144 (44%) for rhinovirus, 15 of 27 (56%) for New OM episodes are usually coincident with a viral up- respiratory syncytial virus, 8 of 11 (73%) and 1 of 5 (20%) per respiratory tract infection (vURTI), but there are con- for influenza A and B, respectively, 6 of 12 (50%) for ad- flicting data regarding the association between specific enovirus, 7 of 18 (39%) for coronavirus, and 4 of 11 (36%) viruses and OM. for parainfluenza virus detections (P=.37). For rhinovi- rus, new OM occurred in 50% of children with and 32% Design: Longitudinal (October-March), prospective fol- without a concurrent CLI (P=.15), and OM risk was pre- low-up of children for coldlike illness (CLI) by diary, middle dicted by OM and breastfeeding histories and by daily ear status by pneumatic otoscopy, and vURTI by PCR. environment outside the home. Setting: Academic medical centers. Conclusions: New OM was associated with nasopha- ryngeal detection of all assayed viruses irrespective of Participants: A total of 102 families with at least 2 chil- the presence or absence of a concurrent CLI. -

Common Ear, Nose & Throat Problems

Common Ear, Nose & Throat Problems The information provided in this presentation is not intended to guide treatment or aid in making a diagnosis. Always consult a physician or nurse practitioner. Copyright 2002, 2014, Kevin T. Kavanagh All Rights Reserved www.entusa.com Normal Larynx Normal larynx in a 44 yr old non-smoker Go to http://www.entusa.com/normal_larynx.htm to View Video Copyright 2002, 2014, Kevin T. Kavanagh All Rights Reserved www.entusa.com Acute Laryngitis This video shows the function of the larynx in a 24 yr old patient with acute laryngitis. Talking was painful and she only talked in a faint whisper. Go to http://www.entusa.com/laryngitis.htm to View Video Copyright 2002, 2014, Kevin T. Kavanagh All Rights Reserved www.entusa.com Vocal Cord Paralysis This video shows the function of a larynx with a paralyzed left true vocal cord. The patient has lung cancer. She has a poorly compensated breathy voice which is difficult to understand. This patient had a 55 pack year history of smoking. Go to http://www.entusa.com/vocal_cord_paralysis_2.htm to View Video Copyright 2002, 2014, Kevin T. Kavanagh All Rights Reserved www.entusa.com Vocal Cord Polyp This video shows the function of a larynx with a vocal cord polyp on the right true vocal cord. This patient smoked one pack a day for 30 years. Go to http://www.entusa.com/larynx_polyp-9.htm to View Video Copyright 2002, 2014, Kevin T. Kavanagh All Rights Reserved www.entusa.com Laryngeal Cancer This video shows the function of a larynx with a large T1b Cancer on both true vocal cords and anterior commissure in 72 yr old male with a 150 pack year history of smoking. -

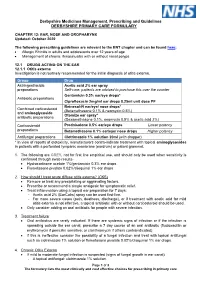

EAR, NOSE and OROPHARYNX Updated: October 2020

Derbyshire Medicines Management, Prescribing and Guidelines DERBYSHIRE PRIMARY CARE FORMULARY CHAPTER 12: EAR, NOSE AND OROPHARYNX Updated: October 2020 The following prescribing guidelines are relevant to the ENT chapter and can be found here: • Allergic Rhinitis in adults and adolescents over 12 years of age • Management of chronic rhinosinusitis with or without nasal polyps 12.1 DRUGS ACTING ON THE EAR 12.1.1 Otitis externa Investigation is not routinely recommended for the initial diagnosis of otitis externa. Group Drug Astringent/acidic Acetic acid 2% ear spray preparations Self-care: patients are advised to purchase this over the counter Gentamicin 0.3% ear/eye drops* Antibiotic preparations Ciprofloxacin 2mg/ml ear drops 0.25ml unit dose PF Betnesol-N ear/eye/ nose drops* Combined corticosteroid (Betamethasone 0.1% & neomycin 0.5%) and aminoglycoside Otomize ear spray* antibiotic preparations (Dexamethasone 0.1%, neomycin 0.5% & acetic acid 2%) Corticosteroid Prednisolone 0.5% ear/eye drops Lower potency preparations Betamethasone 0.1% ear/eye/ nose drops Higher potency Antifungal preparations Clotrimazole 1% solution 20ml (with dropper) * In view of reports of ototoxicity, manufacturers contra-indicate treatment with topical aminoglycosides in patients with a perforated tympanic membrane (eardrum) or patent grommet. 1. The following are GREY, not for first line empirical use, and should only be used when sensitivity is confirmed through swab results- • Hydrocortisone acetate 1%/gentamicin 0.3% ear drops • Flumetasone pivalate 0.02%/clioquinol 1% ear drops 2. How should I treat acute diffuse otitis externa? (CKS) • Remove or treat any precipitating or aggravating factors. • Prescribe or recommend a simple analgesic for symptomatic relief. -

Inner Ear Fibrocytes This Information Is Current As of October 1, 2021

ERK2-Dependent Activation of c-Jun Is Required for Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae-Induced CXCL2 Upregulation in Inner Ear Fibrocytes This information is current as of October 1, 2021. Sejo Oh, Jeong-Im Woo, David J. Lim and Sung K. Moon J Immunol published online 29 February 2012 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/early/2012/02/29/jimmun ol.1103182 Downloaded from Supplementary http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2012/02/29/jimmunol.110318 Material 2.DC1 http://www.jimmunol.org/ Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication by guest on October 1, 2021 *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2012 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. Published February 29, 2012, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1103182 The Journal of Immunology ERK2-Dependent Activation of c-Jun Is Required for Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae-Induced CXCL2 Upregulation in Inner Ear Fibrocytes Sejo Oh,*,1 Jeong-Im Woo,*,1 David J. Lim,*,† and Sung K. Moon* The inner ear, composed of the cochlea and the vestibule, is a specialized sensory organ for hearing and balance.