5. Biological Hazards Risk Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tag out a Shipyard Hazard Prevention Course

Workshop Objectives At the completion of this workshop it is expected that all trainees will pass a quiz, have the ability to identify energy hazards and follow both OSHA and NAVSEA safety procedures associated with: Electrical Hazards Non-Electrical Energy Hazards Lockout - Tag out 11 OSHA 1915.89 SUBPART F Control of Hazardous Energy -Lock-out/ Tags Plus This CFR allows specific exemptions for shipboard tag-outs when Navy Ship’s Force personnel serve as the lockout/tags-plus coordinator and maintain control of the machinery per the Navy’s Tag Out User Manual (TUM). Note to paragraph (c)(4) of this section: When the Navy ship's force maintains control of the machinery, equipment, or systems on a vessel and has implemented such additional measures it determines are necessary, the provisions of paragraph (c)(4)(ii) of this section shall not apply, provided that the employer complies with the verification procedures in paragraph (g) of this section. Note to paragraph (c)(7) of this section: When the Navy ship's force serves as the lockout/tags-plus coordinator and maintains control of the lockout/tags-plus log, the employer will be in compliance with the requirements in paragraph (c)(7) of this section when coordination between the ship's force and the employer occurs to ensure that applicable lockout/tags-plus procedures are followed and documented. 2 Note to paragraph (e) of this section: When the Navy ship's force shuts down any machinery, equipment, or system, and relieves, disconnects, restrains, or otherwise renders safe all potentially hazardous energy that is connected to the machinery, equipment, or system, the employer will be in compliance with the requirements in paragraph (e) of this section when the employer's authorized employee verifies that the machinery, equipment, or system being serviced has been properly shut down, isolated, and deenergized. -

1. Identification

SAFETY DATA SHEET Issuing Date: 13-Aug-2020 Revision date 13-Aug-2020 Revision Number 1 1. IDENTIFICATION Product Name Tide PODS Spring Meadow Product Identifier 91943772_RET_NG Product Type: Finished Product - Retail Recommended use Detergent. Restrictions on use Use only as directed on label. Synonyms C-91943772-005 Details of the supplier of the safety PROCTER & GAMBLE - Fabric and Home Care Division data sheet Ivorydale Technical Centre 5289 Spring Grove Avenue Cincinnati, Ohio 45217-1087 USA Procter & Gamble Inc. P.O. Box 355, Station A Toronto, ON M5W 1C5 1-800-331-3774 E-mail Address [email protected] Emergency Telephone Transportation (24 HR) CHEMTREC - 1-800-424-9300 (U.S./ Canada) or 1-703-527-3887 Mexico toll free in country: 800-681-9531 2. HAZARD IDENTIFICATION "Consumer Products", as defined by the US Consumer Product Safety Act and which are used as intended (typical consumer duration and frequency), are exempt from the OSHA Hazard Communication Standard (29 CFR 1910.1200). This SDS is being provided as a courtesy to help assist in the safe handling and proper use of the product. This product is classified under 29CFR 1910.1200(d) and the Canadian Hazardous Products Regulation as follows:. Hazard Category Acute toxicity - Oral Category 4 Eye Damage / Irritation Category 2B Signal word Warning Hazard statements Harmful if swallowed Causes eye irritation Hazard pictograms 91943772_RET_NG - Tide PODS Spring Meadow Revision date 13-Aug-2020 Precautionary Statements Keep container tightly closed Keep away from heat/sparks/open flames/hot surfaces. — No smoking Wash hands thoroughly after handling Precautionary Statements - In case of fire: Use water, CO2, dry chemical, or foam for extinction Response IF IN EYES: Rinse cautiously with water for several minutes. -

Acute Incidents During Anaesthesia a Small Percentage of Apparently Routine Anaesthetics Will End in an Anticipated Or Unforeseen Acute Incident

Acute incidents during anaesthesia A small percentage of apparently routine anaesthetics will end in an anticipated or unforeseen acute incident. Edwin W Turton, MB ChB, Dip Pec (SA), DA (SA), MMed Anes, FCA (SA) Head of Cardiothoracic Anaesthesia, Bloemfontein Hospitals Complex, Department of Anaesthesiology, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein Dr Edwin Turton worked as a clinical fellow in cardiac anaesthesia at Glenfield Hospital, Leicester, UK, in 2009. His current fields of interest are adult and paediatric cardiac anaesthesia and peri-operative echocardiography, and focussed assessment through echocardiography in emergency care. Correspondence to: E W Turton ([email protected]) Anaesthesia is uneventful in the majority Although anaesthesia is a very well- • Antibiotics (2.6%) of cases but in a small percentage of controlled and governed discipline, acute • Benzodiazepines (2%) routine and emergency cases there will incidents do occur. Incidents can occur • Opioids (1.7%) be an anticipated or an unforeseen acute during induction, maintenance and • Other agents (e.g. radio contrast media) incident. These incidents need immediate emergence from anaesthesia. (2.5%). theoretical knowledge and clinical skills to be managed effectively and to The following acute critical incidents are Treatment and management prevent further morbidity and mortality. discussed in this article: • Stop administration of all suspected Therefore all providers of anaesthesia, • Anaphylaxis agents. at different levels of experience, should • Aspiration • Call for help. be able to provide basic and advanced • Laryngospasm • Airway must be secured and 100% cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).1 • High or total (complete) spinal blocks in oxygen given, and ensure adequate obstetric anaesthesia. ventilation. The first death associated with an anaesthetic • Intravenous or intramuscular adrenaline was reported in 1848 in the USA. -

Personal Protective Equipment Hazard Assessment

WORKER HEALTH AND SAFETY Personal Protective Equipment Hazard Assessment Oregon OSHA Personal Protective Equipment Hazard Assessment About this guide “Personal Protective Equipment Hazard Assessment” is an Oregon OSHA Standards and Technical Resources Section publication. Piracy notice Reprinting, excerpting, or plagiarizing this publication is fine with us as long as it’s not for profit! Please inform Oregon OSHA of your intention as a courtesy. Table of contents What is a PPE hazard assessment ............................................... 2 Why should you do a PPE hazard assessment? .................................. 2 What are Oregon OSHA’s requirements for PPE hazard assessments? ........... 3 Oregon OSHA’s hazard assessment rules ....................................... 3 When is PPE necessary? ........................................................ 4 What types of PPE may be necessary? .......................................... 5 Table 1: Types of PPE ........................................................... 5 How to do a PPE hazard assessment ............................................ 8 Do a baseline survey to identify workplace hazards. 8 Evaluate your employees’ exposures to each hazard identified in the baseline survey ...............................................9 Document your hazard assessment ...................................................10 Do regular workplace inspections ....................................................11 What is a PPE hazard assessment A personal protective equipment (PPE) hazard assessment -

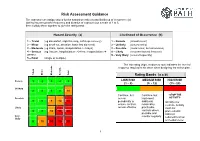

Risk Assessment Guidance

Risk Assessment Guidance The assessor can assign values for the hazard severity (a) and likelihood of occurrence (b) (taking into account the frequency and duration of exposure) on a scale of 1 to 5, then multiply them together to give the rating band: Hazard Severity (a) Likelihood of Occurrence (b) 1 – Trivial (eg discomfort, slight bruising, self-help recovery) 1 – Remote (almost never) 2 – Minor (eg small cut, abrasion, basic first aid need) 2 – Unlikely (occurs rarely) 3 – Moderate (eg strain, sprain, incapacitation > 3 days) 3 – Possible (could occur, but uncommon) 4 – Serious (eg fracture, hospitalisation >24 hrs, incapacitation >4 4 – Likely (recurrent but not frequent) weeks) 5 – Very likely (occurs frequently) 5 – Fatal (single or multiple) The risk rating (high, medium or low) indicates the level of response required to be taken when designing the action plan. Trivial Minor Moderate Serious Fatal Rating Bands (a x b) Remote 1 2 3 4 5 LOW RISK MEDIUM RISK HIGH RISK (1 – 8) (9 - 12) (15 - 25) Unlikely 2 4 6 8 10 Continue, but Continue, but -STOP THE Possible review implement ACTIVITY- 3 6 9 12 15 periodically to additional Identify new ensure controls reasonably controls. Activity Likely remain effective practicable must not controls where 4 8 12 16 20 proceed until possible and risks are Very monitor regularly reduced to a low likely 5 10 15 20 25 or medium level 1 Risk Assessments There are a number of explanations needed in order to understand the process and the form used in this example: HAZARD: Anything that has the potential to cause harm. -

Post-Modern Portfolio Theory Supports Diversification in an Investment Portfolio to Measure Investment's Performance

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Rasiah, Devinaga Article Post-modern portfolio theory supports diversification in an investment portfolio to measure investment's performance Journal of Finance and Investment Analysis Provided in Cooperation with: Scienpress Ltd, London Suggested Citation: Rasiah, Devinaga (2012) : Post-modern portfolio theory supports diversification in an investment portfolio to measure investment's performance, Journal of Finance and Investment Analysis, ISSN 2241-0996, International Scientific Press, Vol. 1, Iss. 1, pp. 69-91 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/58003 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend -

Guidelines for Human Exposure Assessment Risk Assessment Forum

EPA/100/B-19/001 October 2019 www.epa.gov/risk Guidelines for Human Exposure Assessment Risk Assessment Forum EPA/100/B-19/001 October 2019 Guidelines for Human Exposure Assessment Risk Assessment Forum U.S. Environmental Protection Agency DISCLAIMER This document has been reviewed in accordance with U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) policy. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. Preferred citation: U.S. EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). (2019). Guidelines for Human Exposure Assessment. (EPA/100/B-19/001). Washington, D.C.: Risk Assessment Forum, U.S. EPA. Page | ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DISCLAIMER ..................................................................................................................................... ii LIST OF TABLES.............................................................................................................................. vii LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................................... viii LIST OF BOXES ................................................................................................................................ ix ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .............................................................................................. x PREFACE ........................................................................................................................................... xi AUTHORS, CONTRIBUTORS AND -

Environmental Health

Environmental "ealth In Minnesota '·' ! .\ " ' Strengthening Pabllc Healtll Leadership In Environmental Health Il Il I j fml Minnesota · lIDJ Department of Health lli&ilhl ~==~-:.i:.ltft -------- Janaary199J '.~ • - " . Environmental Health In Minnesota Strengthening Public Health Leadership In Environmental Health A Report of the Environmental Health Work Group of the State Community Health Services Advisory Committee Approved December 4, 1992 Published by the ., ,f Minnesota Department of Health Environmental Health In Minnesota Strengthening Public Health Leadership In Environmental Health Table of Contents Introduction . i Work Group charge and membership . ii Part I Background and Recommendations . 1 Contributions of Public Health In Environmental Health and Protection . 3 State Roles In Environmental Health . 6 Local Roles In Environmental Health . 7 Recommendations . 10 Part II Framework For Deciding How to Organize Environmental Services . 13 Keeping a Public Health Perspective In Environmental Health and Protection . 23 Part Ill Profile of Environmental Health In Minnesota . 25 Profile of State Environmental Health . 25 Profile of Local Environmental Health . 26 Current Organization of Local Environmental Health Programs . 31 Part IV Related Documents MACHA Position Paper Current Roles and Challenges of Local Health Departments In Environmental Health, NACHO Directory of State Environmental Health Programs (published separately) Cover art by Kathy Marschall Minnesota Department of Health ) Community Health Seroices Division \ ' ···~ )' Environmental Health In Minnesota + i Introduction Environmental heal.th has been an integral part of the public health mission for over a century. With the rest of public health, environmental health shares a basis In science and a focus on protecting and promoting the health of the public. In the past twenty years an explosion of environmental laws has given greater visibility to . -

Page 1 the Public Health Benefits of Sanitation Interventions

The Public Health Benefits of Sanitation Interventions EPAR Brief No. 104 Jacob Lipson, Professor Leigh Anderson & Professor Susan Bolton Prepared for the Water & Sanitation Team of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Evans School Policy Analysis and Research (EPAR) Professor Leigh Anderson, PI and Lead Faculty Associate Professor Mary Kay Gugerty, Lead Faculty December 10, 2010 Introduction Limited sanitation infrastructure, poor hygienic practices, and unsafe drinking water negatively affect the health of millions of people in the developing world. Using sanitation interventions to interrupt disease pathways can significantly improve public health.1 Sanitation interventions primarily benefit public health by reducing the prevalence of enteric pathogenic illnesses, which cause diarrhea. Health benefits are realized and accrue to the direct recipients of sanitation interventions and also to their neighbors and others in their communities. In a report to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Hutton et al. (2006) estimate that the cost- benefit ratio of sanitation interventions in all developing countries worldwide is 11.2.2 This literature review summarizes the risks of inadequate sanitation to public health and presents the empirical evidence on the public health benefits of complete, intermediate and multiple factor sanitation interventions. The sanitation literature frequently uses inconsistent terminology to describe sanitation infrastructure, technologies and intervention types. Where feasible, we report study results using the original terminology of the authors, while also using consistent terminology to facilitate comparisons across studies. In this review and in much of the literature, sanitation interventions are defined as improvements which provide public or household fecal disposal facilities, and/or improve community fecal disposal and treatment methods.3,4 Sanitation interventions are distinct from water interventions, which focus on increasing access to clean water or improving water quality at drinking water sources or points of use. -

Operational Risk Management Guide

OPERATIONAL RISK MANAGEMENT GUIDE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOREST SERVICE 2020 Last Updated 02/26/2020 RISK MANAGEMENT COUNCIL IN COOPERATION WITH THE OFFICE OF SAFETY & OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH and THE NATIONAL AVIATION SAFETY COUNCIL Contents Contents ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................................. i Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................... 1 What is Operational Risk Management? ................................................................................................................... 1 The Terminology of ORM ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Principles of ORM Application ........................................................................................................................................... 6 The Five-Step ORM Process ................................................................................................................................................ 7 Step 1: Identify Hazards .................................................................................................................................................. -

Safety Manual

Eastern Elevator Safety and Health Manual January 2017 Page 1 of 125 SAFETY AND HEALTH MANUAL Index by Section Number Safety Policy ................................................................................................................. …4 Section 1: General Health and Safety Policies ............................................................. …5 Section 2: Hazard Communication ................................................................................ ..13 Section 3: Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) ......................................................... ..18 Section 4: Emergency Action Plan ................................................................................ ..31 Section 5: Fall Protection .............................................................................................. ..34 Section 6: Ladder Safety ............................................................................................... ..38 Section 7: Bloodborne Pathogens ................................................................................ ..42 Section 8: Motor Vehicle / Fleet Safety ......................................................................... ..47 Section 9: Hearing Conservation .................................................................................. ..50 Section 10: Lockout / Tagout ........................................................................................ ..53 Section 11: Fire Prevention .......................................................................................... -

A PRACTICAL GUIDE for USE of REAL TIME DETECTION SYSTEMS for WORKER PROTECTION and COMPLIANCE with OCCUPATIONAL EXPOSURE LIMITS May 2019

A PRACTICAL GUIDE FOR USE OF REAL TIME DETECTION SYSTEMS FOR WORKER PROTECTION AND COMPLIANCE WITH OCCUPATIONAL EXPOSURE LIMITS May 2019 WHITE PAPER May 2019 A PRACTICAL GUIDE FOR USE OF REAL TIME DETECTION SYSTEMS FOR WORKER PROTECTION AND COMPLIANCE WITH OCCUPATIONAL EXPOSURE LIMITS Prepared by: Energy Facility Contractor’s Group (EFCOG) Industrial Hygiene and Safety Task Group and Members of the American Industrial Hygiene Association (AIHA) Exposure Assessment Strategies Group Dina Siegel1, David Abrams 2, John Hill3, Steven Jahn2, Phil Smith2, Kayla Thomas4 1 Los Alamos National Laboratory 2 AIHA Exposure Assessment Strategies Committee 3 Savannah River Site 4 Kansas City National Security Campus A PRACTICAL GUIDE FOR USE OF REAL TIME DETECTION SYSTEMS FOR WORKER PROTECTION AND COMPLIANCE WITH OCCUPATIONAL EXPOSURE LIMITS May 2019 Table of Contents 1.0 Executive Summary 2.0 Introduction 3.0 Discussion 3.1 Occupational Exposure Assessment 3.2 Regulatory Compliance 3.3 Occupational Exposure Limits 3.4 Traditional Use of Real Time Detection Systems 3.5 Use and Limitations of Real Time Detection Systems 3.6 Use of Real Time Detection Systems for Compliance 3.7 Documentation/Reporting of Real Time Detection Systems Results 3.8 Peak Exposures Data Interpretations 3.9 Conclusions 4.0 Matrices 5.0 References 6.0 Attachments Page | 2 A PRACTICAL GUIDE FOR USE OF REAL TIME DETECTION SYSTEMS FOR WORKER PROTECTION AND COMPLIANCE WITH OCCUPATIONAL EXPOSURE LIMITS May 2019 1.0 Executive Summary This white paper presents practical guidance for field industrial hygiene personnel in the use and application of real time detection systems (RTDS) for exposure monitoring.