Weeds Situation Statement for North West NSW

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Local Strategic Planning Statement Coonamble Shire Council

Local Strategic Planning Statement Coonamble Shire Council April 2020 Adopted by Council: 13/05/2020 Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................................. 3 About the Statement ........................................................................................................................... 4 Consultation ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Our Vision, Our Future ........................................................................................................................ 6 Context ............................................................................................................................................... 8 Our Shire – A Snapshot ................................................................................................................... 8 Our themes and planning priorities .................................................................................................... 12 Community and Place ....................................................................................................................... 13 Priority 1 - Promote and enhance the identity and unique character of Coonamble and the villages of Gulargambone and Quambone.................................................................................................. 14 Priority 2 - Encourage a connected, active and healthy -

Economic Development & Tourism Strategy

Warrumbungle Shire Economic Development & Tourism Strategy 2019 - 2023 1 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. WARRUMBUNGLE SHIRE 4 3. STRATEGIC CONTEXT 20 4. DRIVERS OF CHANGE 28 5. BUILDING OUR ECONOMY 32 6. PRIORITIES, STRATEGIES & ACTIONS 49 7. MONITORING PROGRESS 63 REFERENCES 64 PHOTOGRAPHS 65 WARRUMBUNGLE SHIRE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT & TOURISM STRATEGY Prepared by: JENNY RAND & ASSOCIATES www.jennyrand.com.au WARRUMBUNGLE SHIRE COUNCIL Coonabarabran Office PO Box 191 Coolah Office 14-22 John Street 59 Binnia Street Coonabarabran 2357 Coolah 2843 Website: www.warrumbungle.nsw.gov.au Email: [email protected] Telephone: 02 6849 2000 or 02 6378 5000 Disclaimer: ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Any representation, statement, opinion or advice, expressed or implied, in this document is made in good faith, on the basis that Jenny Rand and Associates, Warrumbungle Shire Council or its employees are not liable (whether Warrumbungle Shire Council wishes to thank all residents, by reason of negligence, lack of care or otherwise) to any person or organisation for any damage or loss businesses and organisations that attended our consultative whatsoever, which has occurred or may occur in relation to that person or organisation taking action in respect forums, met with our staff and consultant and provided information to any representation, statement or advice referred to in the Warrumbungle Shire Economic Development & for our Shire’s Economic Development & Tourism Strategy. Tourism Strategy. Photographs: Front Cover – Canola Fields, David Kirkland Above: Macha Tor, Warrumbungle National Park, David Kirkland 2 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background Located in the central west of NSW, Warrumbungle Shire is a large rural Shire. The Shire’s economy is driven primarily by the agricultural sector, with tourism also a significant contributor. -

Ozsky 2020: Suggested Day Trips, Activities, Guides and Driving

In keeping with our aim of offering the greatest flexibility for all travellers, we don't make bookings for the suggested trips in Sydney, but merely offer a small list of suggestions of what might be of interest to you during your stay in Sydney. The day trips in and around Coonabarabran are also kept reasonably flexible, however firm bookings may be made for some trips, such as any private "inside tours" of observatories, where available. • Sydney Harbour Ferry trip from Circular Quay to Given that most folks visiting OzSky generally stay up until Manly on the commuter ferry (much better than a the early hours of the morning observing, most of the dedicated Harbour Cruise!) optional day trips or activities will be planned to start • The Australian Reptile Park after midday, however some may require an earlier departure based on availability of bookings etc. • Taronga Zoo (also via ferry) • Bondi Beach Afternoon lectures and presentations are often enjoyed • Manly Beach on topics including general astronomy, prime observing • Palm Beach targets, Australian flora and fauna, geology aboriginal culture and more. • Royal Botanical Gardens • City Highlights Half-Day Tours Various day-hikes in the Warrumbungles National Park • Guided / Unguided Tours of the Old Sydney and Pilliga State Forest are also available for all fitness Observatory levels. It should be noted, however, that the region • SCUBA diving around Sydney suffered extreme bushfires back in January 2013 and while many of the popular hikes and tourism areas have • Sydney Aquarium been re-opened, many still show the impact of those • WildLife Sydney Zoo devastating bushfires, even today. -

Parkes Special Activation Precinct Community Statement

COMMUNITY STATEMENT JULY 2019 This statement captures the values and insights shared by Parkes locals, landowners and businesses. It has helped shape the draft master plan for the Parkes Special Activation Precinct. PLACE Master plan and precinct boundaries Relationship to town and Parkes is centrally located, we’ve surrounding farmlands Aboriginal cultural heritage got rail, we’ve got road, we’ve got ENVIRONMENT Biodiversity regional production and we’ll be Sustainability Trees and planting able to capitalise on these things. CONNECTIVITY Roads and rail Geoff Rice Water and waste water Energy and digital connectivity Pedestrian and cycling routes BUILT FORM AND LANDSCAPE Design principles for the look, feel and amenity Public spaces LAND USE AND INDUSTRY Designated sub-precincts for different uses Business attraction and investment Relationship between different industry types SPECIAL ACTIVATION PRECINCT PARKES COMMUNITY STATEMENT | 2 It’s a matter of taking the opportunity to use what we’ve got and use it in a different way. Geoff Rice GEOFF RICE Acknowledgement of Country LANGLANDS HANLON, PRESIDENT PARKES BUSINESS CHAMBER We acknowledge the Wiradjuri people who For the past fourteen years, Geoff and his Geoff and Renee have a nine-year-old daughter are the traditional land owners of the Parkes wife Renee have owned Langlands Hanlon, a and they would like her to have educational Region. The Wiradjuri is the largest Aboriginal livestock station and real-estate agency, right opportunities and employment options in nation in NSW, ranging from Albury in the south in the heart of town. The business has been Parkes or the region. “I’ve got nieces that have to Coonabarabran in the north and covering operating since the mid 1930s, and Geoff had to travel long distances to go to university about one fifth of the State. -

Heavy Vehicle Rest Areas on Key Rural Freight Routes in Nsw

RTA STRATEGY FOR MAJOR HEAVY VEHICLE REST AREAS ON KEY RURAL FREIGHT ROUTES IN NSW JANUARY 2010 This page has been left blank intentionally RTA/Pub. 10.012 ISBN 978-1-921692-69-7 Contents 1. Introduction........................................................................................................................................................................................................1 2. Objectives ...........................................................................................................................................................................................................2 3. Methodology .....................................................................................................................................................................................................2 4. Key rural freight routes in NSW............................................................................................................................................................3 5. Major heavy vehicle rest areas principles.........................................................................................................................................3 6. Targeted level of provision for major heavy rest areas...........................................................................................................4 7. Strategy to address gaps and enhance provision.........................................................................................................................5 8. Summary -

A Double Burial with Grave Goods Near Dubbo, New South Wales

Records of the Australian Museum (1993) Supplement 17. ISBN 0 7310 0280 6 77 The Terramungamine Incident: a Double Burial with Grave Goods near Dubbo, New South Wales DAN WITTERt, RICHARD FULLAGAR2 & COLIN PARDOE3 1 NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, PO Box 459, Broken Hill, NSW 2880, Australia 2 Australian Museum, PO Box A285, Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia 3 Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, GPO Box 553, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia ABSTRACT. In 1987 a female adult skeleton with a small child was found near Dubbo, NSW, during the course of landscape gardening. Although the burials were disturbed by the landscaping work, artefacts found at the time can be associated with the burials. The presence of certain artefacts raises questions concerning the status of the female, and the cause of her death. WITTER, D., R. FULLAGAR & c. PARDOE, 1993. The Terramungamine incident: a double burial with grave goods near Dubbo, New South Wales. Records of the Australian Museum, Supplement 17: 77-89. At a time when archaeologists are becoming more and Although Morwood (1984) suggests that ritual caches more specialised (viz. three authors to this paper), it is were not uncommon in Australia, most human skeletal difficult for one person to maintain the breadth of remains recovered are rarely associated with grave goods. research interests of someone like Fred McCarthy, to To take an example in southeastern Australia, only about whom this volume is dedicated. The less tangible side twenty burials have been recovered with grave goods in of Aboriginal culture associated with death, ritual and all of Victoria (D. -

Dunedoo Pony Club Calendar.Pdf

Horse Riding Events for January - June 2014 JAN 4th 5th 8th/ Dunedoo Pony Club Camp 12th Dunedoo Pony Club Camp 18th 19th 25th 26th FEB 1st 2nd 8th Jumping in the Vines @ Mudgee 9th Jumping in the Vines @ Mudgee 15th Gulgong Show 16th DPC Instruction Day - Triathlon 22nd Rylstone Kandos Show/ Binnaway Show 23rd Sofala Show MAR 1st Mudgee Show 2nd Mudgee Show 8th Dunedoo Show 9th Wongarbon Ribbon Day 15th Rylstone Ribbon Day Coonabarabran Show 16th Zone 6 Showjumping C'Ships @ Rylstone Coonabarabran Show 22nd Dunedoo Ribbon Day Lithgow Show / Baradine Show 23rd Dunedoo Showjumping Day Lithgow Show 29th Mendooran Show / Tamworth Show 30th Mendooran Show / Tamworth Show APR 5th Mudgee Showjumping Championships 6th Mudgee Showjumping Championships 12th NSWPCA SPORTING @ TENTERFIELD 13th NSWPCA C/DRAFTING @ TENTERFIELD 17/18th DPC Trail Ride @ Cobbora 20th Easter Sunday 26th Coolah Ribbon Day NSW PCA Dressage Champs 27th Zone 6 Team Penning @ Coolah NSW PCA Dressage Champs MAY 3rd Bathurst Royal Show / Gunnedah Show 4th Bathurst Royal Show / Gunnedah Show 10th Hargraves Triamble Ribbon Day Bourke Show / Walgett Show 11th Zone 6 Day @ Hargraves Walgett Show 17th Wellington Show 17th NSWPCA JUMPING EQUITATION @ ??? 18th DPC Instruction Day NSWPCA JUMPING EQUITATION @ ??? 24th Dubbo Show 25th Dubbo Show 31st Coona Schools Horse Expo JUN 1st Coona Schools Horse Expo 7th 8th DPC Instruction Day 14th Dunedoo Polocrosse Carnival 15th Dunedoo Polocrosse Carnival 21st 22nd 28th Red Hill Stockmans Challenge @ Gulgong Quambone Polocrosse Carnival 29th -

Warrumbungles Shire

WarrumbungleAstronomy Shire Capital of Australia A History of Condobolin...........................................................................3 A History of Coonabarabran...................................................................3 A History of Coolah ...................................................................................4 A History of Dunedoo ...............................................................................5 A History of Baradine ...............................................................................5 Things you need to know ........................................................................6 All that The Warrumbungle Shire has to Offer .................................7 Communications............................................................................................7 Migrant Support .............................................................................................7 Transport ........................................................................................................8 Main Industry of the Warrumbungles Region..............................................9 Accommodation...........................................................................................10 Real Estate....................................................................................................12 Childcare ......................................................................................................13 Education .....................................................................................................14 -

Part 3 Plant Communities of the NSW Brigalow Belt South, Nandewar An

New South Wales Vegetation classification and Assessment: Part 3 Plant communities of the NSW Brigalow Belt South, Nandewar and west New England Bioregions and update of NSW Western Plains and South-western Slopes plant communities, Version 3 of the NSWVCA database J.S. Benson1, P.G. Richards2 , S. Waller3 & C.B. Allen1 1Science and Public Programs, Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust, Sydney, NSW 2000, AUSTRALIA. Email [email protected]. 2 Ecological Australia Pty Ltd. 35 Orlando St, Coffs Harbour, NSW 2450 AUSTRALIA 3AECOM, Level 45, 80 Collins Street, Melbourne, VICTORIA 3000 AUSTRALIA Abstract: This fourth paper in the NSW Vegetation Classification and Assessment series covers the Brigalow Belt South (BBS) and Nandewar (NAN) Bioregions and the western half of the New England Bioregion (NET), an area of 9.3 million hectares being 11.6% of NSW. It completes the NSWVCA coverage for the Border Rivers-Gwydir and Namoi CMA areas and records plant communities in the Central West and Hunter–Central Rivers CMA areas. In total, 585 plant communities are now classified in the NSWVCA covering 11.5 of the 18 Bioregions in NSW (78% of the State). Of these 226 communities are in the NSW Western Plains and 416 are in the NSW Western Slopes. 315 plant communities are classified in the BBS, NAN and west-NET Bioregions including 267 new descriptions since Version 2 was published in 2008. Descriptions of the 315 communities are provided in a 919 page report on the DVD accompanying this paper along with updated reports on other inland NSW bioregions and nine Catchment Management Authority areas fully or partly classified in the NSWVCA to date. -

A Broad Typology of Dry Rainforests on the Western Slopes of New South Wales

A broad typology of dry rainforests on the western slopes of New South Wales Timothy J. Curran1,2, Peter J. Clarke1, and Jeremy J. Bruhl 1 1 Botany, Centre for Ecology, Evolution and Systematics, University of New England, Armidale NSW 2351, AUSTRALIA. 2 Author for correspondence. Current address: The School for Field Studies, Centre for Rainforest Studies, PO Box 141, Yungaburra, Queensland 4884, AUSTRALIA. [email protected] & [email protected] Abstract: Dry rainforests are those communities that have floristic and structural affinities to mesic rainforests and occur in parts of eastern and northern Australia where rainfall is comparatively low and often highly seasonal. The dry rainforests of the western slopes of New South Wales are poorly-understood compared to other dry rainforests in Australia, due to a lack of regional scale studies. This paper attempts to redress this by deriving a broad floristic and structural typology for this vegetation type. Phytogeographical analysis followed full floristic surveys conducted on 400 m2 plots located within dry rainforest across the western slopes of NSW. Cluster analysis and ordination of 208 plots identified six floristic groups. Unlike in some other regional studies of dry rainforest these groups were readily assigned to Webb structural types, based on leaf size classes, leaf retention classes and canopy height. Five community types were described using both floristic and structural data: 1)Ficus rubiginosa–Notelaea microcarpa notophyll vine thicket, 2) Ficus rubiginosa–Alectryon subcinereus–Notelaea microcarpa notophyll vine forest, 3) Elaeodendron australe–Notelaea microcarpa–Geijera parviflora notophyll vine thicket, 4) Notelaea microcarpa– Geijera parviflora–Ehretia membranifolia semi-evergreen vine thicket, and 5) Cadellia pentastylis low microphyll vine forest. -

Coonabarabran • Baradine • Coolah • Dunedoo Mendooran • Binnaway

Coonabarabran • baradine • Coolah • dunedoo Mendooran • binnaway OFFICIAL VISITORS GUIDE www.warrumbungleregion.com.au Warrumbungle Shire from younger to older a place of many contrasts from museums to memories welcomefrom wine to water to from sculptures to skeletons if it’s history or adventure, the natural or architectural, art or from views to villages science,satisfy the flora diverse or fauna, needs swags of each or saunasmember ... we’veof the gotfamily, something each friend to from biking to buying in the group, each husband or wife, each stop over or tree changer. from bushwalks to bowls from fossils to flix Take a short break or travel the universe, order a long black or tea from culture to community bag, educational, inspirational, challenging and relaxing this is the from nature to neptune life of the Warrumbungle Shire. from parks to pottery from caves to cafés from hats to horseriding We welcome you to our life. ... we’ve got it all ... the only thing missing is YOU! www.warrumbungleregion.com.au e r Across the region there are many sites which indicate a t n e strong link with Aboriginal occupation. The Gamilaroi C n o iandndigenous the Wiradjuri peoples o areccupation the traditional owners i t a and sites have been identified dating back 21,000 years. m r fo Displays in the Keeping Places in Coonabarabran and n history r o Baradine, The Pilliga Forest Discovery Centre, Sculptures it i D is i V in the Scrub and King Togee’s gravesite near Coolah take pr n o ra tod b you on journeys to the dreamtime of the custodians. -

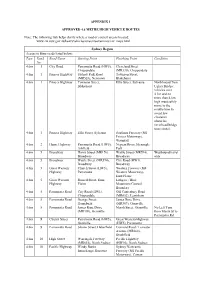

APPENDIX 1 APPROVED 4.6 METRE HIGH VEHICLE ROUTES Note: The

APPENDIX 1 APPROVED 4.6 METRE HIGH VEHICLE ROUTES Note: The following link helps clarify where a road or council area is located: www.rta.nsw.gov.au/heavyvehicles/oversizeovermass/rav_maps.html Sydney Region Access to State roads listed below: Type Road Road Name Starting Point Finishing Point Condition No 4.6m 1 City Road Parramatta Road (HW5), Cleveland Street Chippendale (MR330), Chippendale 4.6m 1 Princes Highway Sydney Park Road Townson Street, (MR528), Newtown Blakehurst 4.6m 1 Princes Highway Townson Street, Ellis Street, Sylvania Northbound Tom Blakehurst Ugly's Bridge: vehicles over 4.3m and no more than 4.6m high must safely move to the middle lane to avoid low clearance obstacles (overhead bridge truss struts). 4.6m 1 Princes Highway Ellis Street, Sylvania Southern Freeway (M1 Princes Motorway), Waterfall 4.6m 2 Hume Highway Parramatta Road (HW5), Nepean River, Menangle Ashfield Park 4.6m 5 Broadway Harris Street (MR170), Wattle Street (MR594), Westbound travel Broadway Broadway only 4.6m 5 Broadway Wattle Street (MR594), City Road (HW1), Broadway Broadway 4.6m 5 Great Western Church Street (HW5), Western Freeway (M4 Highway Parramatta Western Motorway), Emu Plains 4.6m 5 Great Western Russell Street, Emu Lithgow / Blue Highway Plains Mountains Council Boundary 4.6m 5 Parramatta Road City Road (HW1), Old Canterbury Road Chippendale (MR652), Lewisham 4.6m 5 Parramatta Road George Street, James Ruse Drive Homebush (MR309), Granville 4.6m 5 Parramatta Road James Ruse Drive Marsh Street, Granville No Left Turn (MR309), Granville