Observing Photons in Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CR-/3017S B ORBITING SOLAR OBSERVATORY FINAL REPORT

4: it W::: 050-7 ~AS ACR-/3017s B ORBITING SOLAR OBSERVATORY FINAL REPORT N C) U2a ~ 0mU 4~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~-4' W 10 ~~~~~~ -7 Ol C",.1-a -9- ---- o ' ocl '.-l Q) o QU2i~WL4cO 1-a . ), 3xr N~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~. .~ tjir~ V I ed F7. 3 wUii rH1 _.1- ~~z,~~OULECORD r~ BALBOTESRSERHCRPRTO o~~~~~USDAY FBL OPRTO BOULDER, COLRAD I~ ~..... LDER-'COLOR.DO '-01 OSO-7 ORBITING SOLAR OBSERVATORY PROGRAM FINAL REPORT F72-01 December 31, 1972 PREPARED BY APPROVED BY OSO Program Staff J. O. Simpson Director, OSO Programs BALL BROTHERS RESEARCH CORPORATION SUBSIDIARY OF BALL CORPORATION BOULDER, COLORADO F72-01 PREFACE During the 1950's rapid progress was made in solar physics and in instrument and space hardware technology, using rocket and balloon flights that, although of brief duration, provided a view of the sun free from the obscuring atmosphere. The significance of data from these flights confirmed the often-asserted value of long-term observations from a spacecraft in advancing our knowledge of the sun's behavior. Thus, the first of NASA's space platforms designed for long-term observations of the universe from above the atmosphere was planned, and the Orbiting Solar Observatory program started in 1959. Solar physics data return began with the launch of OSO-1 in March of 1962. OSO-2 and OSO-3 were launched in 1965, OSO-4 and OS0-5 in 1967, OSO-6 in 1969, and the most recent, OSO-7/, was launched on September 29, 1971. All seven OSO's have been highly successful both in scientific data return and in per- formance of the engineering systems. -

The Status and Future of EUV Astronomy

The status and future of EUV astronomy M. A. Barstow∗, S. L. Casewell Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Leicester, University Road, Leicester, LE1 7RH, UK J. B. Holberg Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, 1541 East University Boulevard, Sonett Space Sciences Building, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA M.P. Kowalski Naval Research Laboratory,4555 Overlook Ave SW Washington, DC 20375, USA Abstract The Extreme Ultraviolet wavelength range was one of the final windows to be opened up to astronomy. Nevertheless, it provides very important diagnostic tools for a range of astronomical objects, although the opacity of the interstellar medium restricts the majority of observations to sources in our own galaxy. This review gives a historical overview of EUV astronomy, describes current instrumental capabilities and examines the prospects for future facilities on small and medium-class satellite platforms. Keywords: Extreme Ultraviolet, Spectroscopy, White Dwarfs, Stellar Coronae, Interstellar Medium 1. Introduction arXiv:1309.2181v1 [astro-ph.SR] 9 Sep 2013 The Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) nominally spans the wavelength range from 100 to 912 A,˚ although for practical purposes the edges are often some- what indistinct as instrument band-passes may extend short-ward into the soft X-ray or long-ward into the far ultraviolet (far-UV). The production of EUV photons is primarily associated with the existence of hot, 105-107 K gas ∗Corresponding Author: [email protected] Preprint submitted to Advances in Space Research October 29, 2018 in the Universe. Sources of EUV radiation can be divided into two main cat- egories, those where the emission arises from recombination of ions and elec- trons in a hot, optically thin plasma, giving rise to emission line spectra, and objects which are seen by thermal emission from an optically thick medium, resulting in a strong continuum spectrum which may contain features arising from transitions between different energy levels or ionisation stages of sev- eral elements. -

Information Summaries

TIROS 8 12/21/63 Delta-22 TIROS-H (A-53) 17B S National Aeronautics and TIROS 9 1/22/65 Delta-28 TIROS-I (A-54) 17A S Space Administration TIROS Operational 2TIROS 10 7/1/65 Delta-32 OT-1 17B S John F. Kennedy Space Center 2ESSA 1 2/3/66 Delta-36 OT-3 (TOS) 17A S Information Summaries 2 2 ESSA 2 2/28/66 Delta-37 OT-2 (TOS) 17B S 2ESSA 3 10/2/66 2Delta-41 TOS-A 1SLC-2E S PMS 031 (KSC) OSO (Orbiting Solar Observatories) Lunar and Planetary 2ESSA 4 1/26/67 2Delta-45 TOS-B 1SLC-2E S June 1999 OSO 1 3/7/62 Delta-8 OSO-A (S-16) 17A S 2ESSA 5 4/20/67 2Delta-48 TOS-C 1SLC-2E S OSO 2 2/3/65 Delta-29 OSO-B2 (S-17) 17B S Mission Launch Launch Payload Launch 2ESSA 6 11/10/67 2Delta-54 TOS-D 1SLC-2E S OSO 8/25/65 Delta-33 OSO-C 17B U Name Date Vehicle Code Pad Results 2ESSA 7 8/16/68 2Delta-58 TOS-E 1SLC-2E S OSO 3 3/8/67 Delta-46 OSO-E1 17A S 2ESSA 8 12/15/68 2Delta-62 TOS-F 1SLC-2E S OSO 4 10/18/67 Delta-53 OSO-D 17B S PIONEER (Lunar) 2ESSA 9 2/26/69 2Delta-67 TOS-G 17B S OSO 5 1/22/69 Delta-64 OSO-F 17B S Pioneer 1 10/11/58 Thor-Able-1 –– 17A U Major NASA 2 1 OSO 6/PAC 8/9/69 Delta-72 OSO-G/PAC 17A S Pioneer 2 11/8/58 Thor-Able-2 –– 17A U IMPROVED TIROS OPERATIONAL 2 1 OSO 7/TETR 3 9/29/71 Delta-85 OSO-H/TETR-D 17A S Pioneer 3 12/6/58 Juno II AM-11 –– 5 U 3ITOS 1/OSCAR 5 1/23/70 2Delta-76 1TIROS-M/OSCAR 1SLC-2W S 2 OSO 8 6/21/75 Delta-112 OSO-1 17B S Pioneer 4 3/3/59 Juno II AM-14 –– 5 S 3NOAA 1 12/11/70 2Delta-81 ITOS-A 1SLC-2W S Launches Pioneer 11/26/59 Atlas-Able-1 –– 14 U 3ITOS 10/21/71 2Delta-86 ITOS-B 1SLC-2E U OGO (Orbiting Geophysical -

OSO 20M Telescope Handbook

OSO 20m Telescope Handbook Onsala Space Observatory August 31, 2016 The latest version of this handbook can be found here. Original version by Lars E.B. Johansson. Latest revisions by A.O.H.Olofsson and E. De Beck. Table of Contents Contents2 List of Figures5 List of Tables6 1 Introduction7 1 Quick system overview..........................7 2 Observing.................................8 3 Staff....................................9 4 Communication..............................9 2 Technical description 10 1 The telescope............................... 10 2 Receivers / frontends........................... 10 2.1 3 mm: 85 – 116 GHz........................ 11 2.2 4 mm: 67 – 87 GHz........................ 12 2.3 100 GHz receiver......................... 12 3 Spectrometers / backends........................ 14 4 Telescope and instrument control system................ 15 3 Spectral-line observations 16 1 Observing modes............................. 16 1.1 Beam switching.......................... 16 1.2 Position switching......................... 17 1.3 Frequency switching....................... 17 1.4 Mapping.............................. 17 2 Calibration................................ 18 3 Pointing strategy............................. 18 4 Velocity systems.............................. 18 5 Time estimates.............................. 19 6 Atmospheric transmission........................ 20 4 Data 22 1 Backups, retrieval and transfer...................... 22 2 File names................................. 22 2 OSO 20 m Telescope Handbook Table -

Pokroky Kosmické Astronomie

Pokroky matematiky, fyziky a astronomie Marcel Grün; Pavel Koubský Pokroky kosmické astronomie Pokroky matematiky, fyziky a astronomie, Vol. 15 (1970), No. 2, 62--76 Persistent URL: http://dml.cz/dmlcz/138230 Terms of use: © Jednota českých matematiků a fyziků, 1970 Institute of Mathematics of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic provides access to digitized documents strictly for personal use. Each copy of any part of this document must contain these Terms of use. This paper has been digitized, optimized for electronic delivery and stamped with digital signature within the project DML-CZ: The Czech Digital Mathematics Library http://project.dml.cz POKROKY KOSMICKÉ ASTRONOMIE MARCEL GRÚN, PAVEL KOUBSKÝ, Praha Astronomická pozorování konaná ze zemského povrchu jsou znesnadňována přítomností atmosféry, která se chová jako filtr se specifickými vlastnostmi: 1. Je nepropustná pro většinu frekvencí elektromagnetických vln přicházejících z vesmíru (obr. I). 2. Omezuje rozlišovací schopnost v těch oborech, které propouští. Vzhledem k difrakci světla je teoretická rozlišovací schopnost přímoúměrná apertuře (průměru objektivu) a nepřímo- úměrná vlnové délce. To však platí pouze pro ideální podmínky, neboť turbulence atmosféry nedovoluje rozlišit ve viditelném oboru více než 0,1". Obvyklé pozorovací podmínky snižují tuto hodnotu nejméně o řád; třiceticentimetrový dalekohled ve vakuu je po stránce praktické rozlišo vací schopnosti ekvivalentní největším pozemským přístrojům. 3. Pozorování je rušeno existencí vlastního záření atmosféry a přítomností záření rozptýleného v atmosféře. Rozptýlené záření způsobuje, že dosah největších fotografických dalekohledů je nižší, než by odpovídalo optice a citlivosti detektorů. Záření atmosféry je překážkou též při spektrální analýze slabých objektů. Ve zprávě [1] se předpokládá, že třímetrový reflektor na oběž né dráze pointovaný s přesností 0,004" by byl schopen zachytit objekty do 29m, o 2 řády méně jasné než dosud ze Země. -

UV and Infrared Astronomy

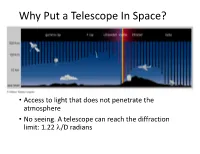

Why Put a Telescope In Space? • Access to light that does not penetrate the atmosphere • No seeing. A telescope can reach the diffraction limit: 1.22 l/D radians Astronomy in Space. I. UV Astronomy Ultraviolet Astronomy 912-3650 Å (Lyman Limit to Balmer jump) • Continuua of hot stars (spectral types O,B,A) • H I Lyman lines (1-n transitions) • Resonance lines of Li-like ions C IV, N V, O VI • H2 Lyman and Werner bands Normal incidence optics • Special UV-reflective coatings The Far Ultraviolet 912 to 1150 Å • Defined by Lyman limit, MgF cutoff at 1150 Å • LiF + Al reflects longward of 1050 Å • SiC reflects at shorter wavelengths The Astronomy Quarterly, Vol. 7, pp. 131-142, 1990 0364-9229f90 $3.00+.00 Printed in the USA. All rights reserved. Copyright (c) 1990 Pergamon Press plc ASTRONOMICAL ADVANTAGES History OFAN • 9/1/1946: Lyman Spitzer EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL OBSERVATORY proposed a Space Telescope in LYMAN SPITZER, Jr. ’ a Report to project Rand This study points out, in a very preliminary way, the results that might be expected from astronomical measurements made with a satellite • 1966: Spitzer (Princeton) vehicle. The discussion is divided into three parts, corresponding to three different assumptions concerning the amount of instrumentation provided. chairs NASA Ad Hoc In the first section it is assumed that no telescope is provided; in the second a 10-&h reflector is assumed; in the third section some of the results Committee on the "Scientific obtainable with a large reflecting telescope, many feet in diameter, and revolving about the earth above the terrestrial atmosphere, are briefly Uses of the Large Space sketched. -

GRAVITY ASTROPHYSICS a Plan for the 1990S

ULTRAVIOLET, VISIBLE, and GRAVITY ASTROPHYSICS A Plan for the 1990s (NASA-NP-I52) ULTRAVIOLET, N94-24973 VISI3LE, ANO GRAVITY ASTROPHYSICS: A PLAN FOR THE 1990'S (NASA) 76 p Unclas HI190 0207794 ORIGINAL PAGE COLOR PHOTOGRAPH National Aeronautics and Space Administration I-oreword N ASA'sprioritiesOfficefrom oftheSpaceU.S. NationalScience Academyand Applicationsof Sciences.(OSSA)Guidancereceivesto theadviceOSSAon Astrophysicsscientific strategyDivision,and in particular, is provided by dedicated Academy committees, ad hoc study groups and, at 10-year intervals, by broadly mandated astronomy and astrophysics survey committees charged with making recommen- dations for the coming decade. Many of the Academy's recommendations have important implications for the conduct of ultraviolet and visible-light astronomy from space. Moreover, these areas are now poised for an era of rapid growth. Through technological progress, ultraviolet astronomy has already risen from a novel observational technique four decades ago to the mainstream of astronomical research today. Recent developments in space technology and instrumen- tation have the potential to generate comparably dramatic strides in observational astronomy within the next 10 years. In 1989, the Ultraviolet and Visible Astrophysics Branch of the OSSA Astrophysics Division recognized the need for a new, long-range plan that would implement the Academy's recommendations in a way that yielded the most advantageous use of new technology. NASA's Ultraviolet, Visible, and Gravity Astrophysics Management Operations Working Group was asked to develop such a plan for the 1990s. Since the Branch holds programmatic responsibility for space research in gravitational physics and relativity, as well as for ultraviolet and visible-light astrophysics, missions in those areas were also included. -

Photographs Written Historical and Descriptive

CAPE CANAVERAL AIR FORCE STATION, MISSILE ASSEMBLY HAER FL-8-B BUILDING AE HAER FL-8-B (John F. Kennedy Space Center, Hanger AE) Cape Canaveral Brevard County Florida PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD SOUTHEAST REGIONAL OFFICE National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 100 Alabama St. NW Atlanta, GA 30303 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD CAPE CANAVERAL AIR FORCE STATION, MISSILE ASSEMBLY BUILDING AE (Hangar AE) HAER NO. FL-8-B Location: Hangar Road, Cape Canaveral Air Force Station (CCAFS), Industrial Area, Brevard County, Florida. USGS Cape Canaveral, Florida, Quadrangle. Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates: E 540610 N 3151547, Zone 17, NAD 1983. Date of Construction: 1959 Present Owner: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Present Use: Home to NASA’s Launch Services Program (LSP) and the Launch Vehicle Data Center (LVDC). The LVDC allows engineers to monitor telemetry data during unmanned rocket launches. Significance: Missile Assembly Building AE, commonly called Hangar AE, is nationally significant as the telemetry station for NASA KSC’s unmanned Expendable Launch Vehicle (ELV) program. Since 1961, the building has been the principal facility for monitoring telemetry communications data during ELV launches and until 1995 it processed scientifically significant ELV satellite payloads. Still in operation, Hangar AE is essential to the continuing mission and success of NASA’s unmanned rocket launch program at KSC. It is eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) under Criterion A in the area of Space Exploration as Kennedy Space Center’s (KSC) original Mission Control Center for its program of unmanned launch missions and under Criterion C as a contributing resource in the CCAFS Industrial Area Historic District. -

The Very-High-Energy Gamma-Ray Sky and the CTA Observatory

The very-high-energy gamma-ray sky and the CTA Observatory Jürgen Knödlseder (IRAP, Toulouse) Directeur de Recherche (CNRS) The menu Light starter I. Why we do gamma-ray astronomy Assortment of AppeMzers II. What have we learned so far Main Dish III. What comes next Desert IV. Concluding remarks First course I. Why we do gamma-ray astronomy A historical introducMon The discovery of cosmic rays 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 Viktor Franz Hess (1912) 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 The nature of cosmic rays 1910 Charged 1920 parMcles! Gamma 1930 rays! 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 Robert Millikan and Arthur Holly Compton (1931) A hot debate (1932) 2000 2010 Cosmic charged parMcles ! 1910 1920 1930 1940 MS ChrisMan Huygens 1950 Clay and Berlage (1932) 1960 1970 Geiger counter 1980 4 cm gold bar 1990 Geiger counter 2000 Bothe and Kohlhörster (1929) 2010 Cosmic stac 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 Karl Jansky (1933) 2010 An ambiMous amateur 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 Grote Reber (1944) 2010 … and the first radio sky map 1910 1920 Cas A 1930 Cygnus X 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 Galactic centre 1990 2000 2010 Synchrotron radiaon 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 Langmuir,Elder,Gurevitsch, 1970 Charleton et Pollock (1948) 1980 1990 2000 Discovery of synchrotron radiaon (1947) 2010 Consequences 1910 Cosmic-ray parMcles emit gamma rays! 1920 1930 Hayakawa (1952) 1940 Hutchinson (1952) 1950 1960 Feenberg and Primakoff (1948) 1970 1980 Curvature Radiation 1990 2000 2010 Radhakrishnan and Cooke (1969) Philip Morrison (1958) -

Table of Artificial Satellites Launched Between 1 January and 31 December 1967

This electronic version (PDF) was scanned by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Library & Archives Service from an original paper document in the ITU Library & Archives collections. La présente version électronique (PDF) a été numérisée par le Service de la bibliothèque et des archives de l'Union internationale des télécommunications (UIT) à partir d'un document papier original des collections de ce service. Esta versión electrónica (PDF) ha sido escaneada por el Servicio de Biblioteca y Archivos de la Unión Internacional de Telecomunicaciones (UIT) a partir de un documento impreso original de las colecciones del Servicio de Biblioteca y Archivos de la UIT. (ITU) ﻟﻼﺗﺼﺎﻻﺕ ﺍﻟﺪﻭﻟﻲ ﺍﻻﺗﺤﺎﺩ ﻓﻲ ﻭﺍﻟﻤﺤﻔﻮﻇﺎﺕ ﺍﻟﻤﻜﺘﺒﺔ ﻗﺴﻢ ﺃﺟﺮﺍﻩ ﺍﻟﻀﻮﺋﻲ ﺑﺎﻟﻤﺴﺢ ﺗﺼﻮﻳﺮ ﻧﺘﺎﺝ (PDF) ﺍﻹﻟﻜﺘﺮﻭﻧﻴﺔ ﺍﻟﻨﺴﺨﺔ ﻫﺬﻩ .ﻭﺍﻟﻤﺤﻔﻮﻇﺎﺕ ﺍﻟﻤﻜﺘﺒﺔ ﻗﺴﻢ ﻓﻲ ﺍﻟﻤﺘﻮﻓﺮﺓ ﺍﻟﻮﺛﺎﺋﻖ ﺿﻤﻦ ﺃﺻﻠﻴﺔ ﻭﺭﻗﻴﺔ ﻭﺛﻴﻘﺔ ﻣﻦ ﻧﻘﻼ ً◌ 此电子版(PDF版本)由国际电信联盟(ITU)图书馆和档案室利用存于该处的纸质文件扫描提供。 Настоящий электронный вариант (PDF) был подготовлен в библиотечно-архивной службе Международного союза электросвязи путем сканирования исходного документа в бумажной форме из библиотечно-архивной службы МСЭ. © International Telecommunication Union HIS list of artificial satellites launched in 1967 was prepared from information provided by TTelecommunication Administrations, the Com m ittee on Space Research (COSPAR), the Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC), the United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the International Fre quency Registration Board (IFRB), one of the fo ur permanent organs o f the ITU, and from details published in the specialized press. For decayed satellites the data concerning the orbit parameters are those immediately after launching. For the others, still in orbit, the orbit parameters are those reported on 31 De cember 1967 by GSFC. -

Where Are All the Sirius-Like Binary Systems?

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 1-22 (2013) Printed 20/08/2013 (MAB WORD template V1.0) Where are all the Sirius-Like Binary Systems? 1* 2 3 4 4 J. B. Holberg , T. D. Oswalt , E. M. Sion , M. A. Barstow and M. R. Burleigh ¹ Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, Sonnett Space Sciences Bld., University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA 2 Florida Institute of Technology, Melbourne, FL. 32091, USA 3 Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Villanova University, 800 Lancaster Ave. Villanova University, Villanova, PA, 19085, USA 4 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Leicester, University Road, Leicester LE1 7RH, UK 1st September 2011 ABSTRACT Approximately 70% of the nearby white dwarfs appear to be single stars, with the remainder being members of binary or multiple star systems. The most numerous and most easily identifiable systems are those in which the main sequence companion is an M star, since even if the systems are unresolved the white dwarf either dominates or is at least competitive with the luminosity of the companion at optical wavelengths. Harder to identify are systems where the non-degenerate component has a spectral type earlier than M0 and the white dwarf becomes the less luminous component. Taking Sirius as the prototype, these latter systems are referred to here as ‘Sirius-Like’. There are currently 98 known Sirius-Like systems. Studies of the local white dwarf population within 20 pc indicate that approximately 8 per cent of all white dwarfs are members of Sirius-Like systems, yet beyond 20 pc the frequency of known Sirius-Like systems declines to between 1 and 2 per cent, indicating that many more of these systems remain to be found. -

Division a Fundamental Astronomy NC-‐5 Gravitational Wave

25/11/14 1 TM LoIs for Commissions: http://www.iau.org/submissions/commissionproposal/list/ Sorted by "Parent Divisions" (or by "Cross-Divisions") Titles may be abridged. Division A Fundamental Astronomy NC-5 Gravitational Wave Astronomy NC-9 Astrometry NC-10 Computational Astrophysics NC-18 Rotation of the Earth NC-23 Dynamical Astronomy NC-26 Solar System Ephemerides NC-30 Fundamental Standards NC-36 Gravitational Lensing NC-46 Time Division B Facitilities, Technologies & Data Science NC-5 Gravitational Wave Astronomy NC-6 Computational Astrophysics NC-10 Computational Astrophysics NC-15 Photometry and Polarimetry NC-19 Ultraviolet Astronomy NC-21 Data and Documentation NC-27 Astronomical Telescopes NC-29 Time Domain Astronomy NC-34 Radio Astronomy NC-35 Optical and IR Interferometry NC-41 Astrostatistics & Astroinformatics NC-42 Laboratory Astrophysics NC-55 Protection of Observatory Sites NC-56 Computational Astrophysics Division C Education, Outreach & Heritage NC-10 Computational Astrophysics NC-11 Astronomy Education & Development NC-20 Astronomical Heritage NC-52 Astronomical Discoveries & Alerts NC-54 Communicating Astronomy NC-57 History of Astronomy Division D High-Energy Phenomena & Fundamental Physics NC-5 Gravitational Wave Astronomy NC-39 Gravitational Wave Astrophysics NC-44 Supernovae NC-53 BH & Evolution of Galaxies Division E Sun & Heliosphere NC-37 Solar Radiation and Structure NC-45 Space Weather etc. NC-49 Solar Activity 25/11/14 2 TM Division F Planetary Systems & Bioastronomy NC-12 Celestial Spectroscopy NC-13 Astrobiology