Corbridge Northumberland Extensive Urban Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fantastic W Ays to Travel and Save Money with Go North East Travelling with Uscouldn't Be Simpler! Ten Services Betw Een

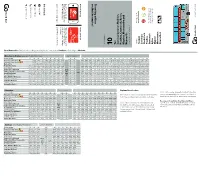

money with Go North East money and save travel to ways Fantastic couldn’t be simpler! couldn’t with us Travelling gonortheast.co.uk the Go North East app. mobile with your to straight times and tickets Live Go North app East Get in touch gonortheast.co.uk 420 5050 0191 @gonortheast simplyGNE 5 mins 5 mins gonortheast.co.uk /gneapp Buses run up to Buses run up to 30 minutes every ramp access find You’ll bus and travel on every on board. advice safety gonortheast.co.uk smartcard. deals on exclusive with everyone, easier for cheaper and travel Makes smartcard the key /thekey the key the key Serving: Hexham Corbridge Stocksfield Prudhoe Crawcrook Ryton Blaydon Metrocentre Newcastle Go North East 10 Bus times from 21 May 2017 21 May Bus times from Ten Ten Hexham, between Services Ryton, Crawcrook, Prudhoe, and Metrocentre Blaydon, Newcastle 10 — Newcastle » Metrocentre » Blaydon » Ryton » Crawcrook » Prudhoe » Corbridge » Hexham Mondays to Fridays (except Public Holidays) Every 30 minutes at Service number 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10X 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 Newcastle Eldon Square - 0623 0645 0715 0745 0815 0855 0925 0955 25 55 1355 1425 1455 1527 1559 1635 1707 1724 1740 1810 1840 1900 1934 1958 2100 2200 2300 Newcastle Central Station - 0628 0651 0721 0751 0821 0901 0931 1001 31 01 1401 1431 1501 1533 1606 1642 1714 1731 1747 1817 1846 1906 1940 2003 2105 2205 2305 Metrocentre - 0638 0703 0733 0803 0833 0913 0944 1014 44 14 1414 1444 1514 1546 1619 1655 1727 X 1800 1829 1858 1919 1952 2016 2118 2218 2318 Blaydon -

The Coach House, Sandhoe, Hexham, Northumberland

THE COACH HOUSE, SANDHOE, HEXHAM, NORTHUMBERLAND THE COACH HOUSE SANDHOE, HEXHAM, NORTHUMBERLAND An imaginatively-converted and extended period home within this highly-regarded and historic hamlet, providing beautifully-appointed family accommodation. Approximate mileages Corbridge 2.5 miles • Hexham 3.5 miles • Newcastle 20 miles • Carlisle 40.5 miles Durham 36.5 miles • Edinburgh 93 miles Accommodation in brief Ground Floor Breakfasting Kitchen, Dining Hall, Gym/Bedroom with En-suite, Master Bedroom with En-suite Shower Room and Dressing Room First Floor Sitting Room, Living Room, Study/Bedroom, 2 Bedrooms, Bathroom Corbridge office Eastfield House Main Street Corbridge Northumberland NE45 5LD t 01434 632404 [email protected] Situation Accommodation Sandhoe lies on the south-facing slopes of the Tyne To the front of the property is a storm porch with Valley, in an elevated position between Corbridge part-glazed inner doorway leading through to the and Hexham. This historic hamlet is dominated by splendid dining hall having vaulted ceiling to part Sandhoe Hall and Beaufront Castle along with an and painted beams to the remainder. There is interesting variety of impressive houses and cottages. tiled flooring throughout along with a useful cloaks There is easy access to the A69, linking Newcastle cupboard and French doorways out to the gardens. and Carlisle as well as Hexham and Corbridge. There is also an under stair storage cupboard. The beautifully-appointed breakfast kitchen is fitted with A broad range of shopping, educational and a comprehensive range of units by the Newcastle recreational facilities are, therefore, readily accessible Furniture Company with a central, stainless-steel and the location is ideal for the commuter. -

La Libellule

LA LIBELLULE FENROTHER | MORPETH | NORTHUMBERLAND A superb barn conversion with high quality interior situated in a rural yet accessible location LA LIBELLULE FENROTHER | MORPETH | NORTHUMBERLAND APPROXIMATE MILEAGES Morpeth 6.0 miles | Alnwick 15.1 miles | Newcastle International Airport 20.3 miles Newcastle City Centre 21.0 miles ACCOMMODATION IN BRIEF Entrance Hall | Sitting Room | Kitchen/Breakfast Room | Utility Room | Cloakroom Master Bedroom with En-suite Shower Room | Two Further Bedrooms | Family Bathroom Gardens | Parking Finest Properties | Crossways | Market Place | Corbridge | Northumberland | NE45 5AW T: 01434 622234 E: [email protected] finest properties.co.uk THE PROPERTY La Libellule is a delightful stone built barn conversion nestled within a select development with two other properties which was completed in 2008. The property offers a wealth of charm throughout, sympathetically blending the original character with a more modern day feel. The front door enters into a naturally bright entrance hall with flagstone floor, stairs to the first floor and access to the ground floor accommodation. The sitting room sits to one side, offering generous proportions and dual aspect to the north and west. A wood burning stove with stone mantle surround by Chesneys provides a focal point to the room with exposed beams and oak flooring adding to the character. The kitchen/breakfast room provides a good range of bespoke, painted wooden units with contrasting wooden and granite work surfaces as well as Fired Earth tiles to the floor and walls. Integral appliances include a dishwasher, Belfast sink and Rangemaster cooker, whilst a useful utility room accessed off the kitchen has further storage, sink and plumbing for a washing machine. -

Trains Tyne Valley Line

From 15th May to 2nd October 2016 Newcastle - Hexham - Carlisle Northern Mondays to Fridays Gc¶ Hp Mb Mb Mb Mb Gc¶ Mb Sunderland dep … … 0730 0755 0830 … 0930 … … 1030 1130 … 1230 … 1330 Newcastle dep 0625 0646 0753 0824 0854 0924 0954 1024 1054 1122 1154 1222 1254 1323 1354 Dunston 0758 0859 Metrocentre 0634 0654 0802 0832 0903 0932 1002 1033 1102 1132 1202 1232 1302 1333 1402 Blaydon 0639 | 0806 | 1006 | | 1206 | | 1406 Wylam 0645 0812 0840 0911 1012 1110 1212 1310 1412 Prudhoe 0649 0704 0817 0844 0915 0942 1017 1043 1114 1142 1217 1242 1314 1344 1417 Stocksfield 0654 | 0821 0849 0920 | 1021 | 1119 | 1221 | 1319 | 1421 Riding Mill 0658 | 0826 | 0924 | 1026 | 1123 | 1226 | 1323 | 1426 Corbridge 0702 0830 0928 1030 1127 1230 1327 1430 Hexham arr 0710 0717 0838 0858 0937 0955 1038 1055 1137 1155 1238 1255 1337 1356 1438 Hexham dep … 0717 … 0858 … 0955 … 1055 … 1155 … 1255 … 1357 … Haydon Bridge … 0726 … 0907 … | … 1104 … | … 1304 … | … Bardon Mill … 0733 … 0914 … … 1111 … … 1311 … … Haltwhistle … 0740 … 0921 … 1014 … 1118 … 1214 … 1318 … 1416 … Brampton … 0755 … 0936 … | … 1133 … | … 1333 … | … Wetheral … 0804 … 0946 … … 1142 … … 1342 … … Carlisle arr … 0815 … 0957 … 1046 … 1157 … 1247 … 1354 … 1448 … Mb Mb Wv Mb Gc¶ Mb Ct Mb Sunderland dep … 1430 … 1531 … 1630 … … 1730 … 1843 1929 2039 2211 Newcastle dep 1424 1454 1524 1554 1622 1654 1716 1724 1754 1824 1925 2016 2118 2235 Dunston 1829 Metrocentre 1432 1502 1532 1602 1632 1702 1724 1732 1802 1833 1934 2024 2126 2243 Blaydon | | 1606 -

FOI 1155-17 Police Stations

Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA) Request 835/15 - Police station closures As at 31.12.2005 31.12.2006 31.12.2007 & 2008 As at 31.12.2009 As at 31.12.2010 As at 31.12. 2011 As at 31.12.2012 to 2013 As at 31.12 2014 As at Sept.2015 As at October 2016 As at October 2017 Forecast to 31/3/2018 Status Relocated to (i) Unit 7, Signal House, Waterloo Place. (ii) Sunderland Central Fire Station, Railway Row, Sunderland. 1 Gillbridge Gillbridge Gillbridge Gillbridge Gillbridge Gillbridge Gillbridge Gillbridge Gillbridge (iii) The Old Orphanage, Hendon SOLD 2 Washington Washington Washington Washington Washington Washington Washington Washington Washington Washington Washington Washington 3 Millbank - South Shields Millbank - South Shields Millbank - South Shields Millbank - South Shields Millbank - South Shields Millbank - South Shields Millbank - South Shields Millbank - South Shields Millbank - South Shields Millbank - South Shields Millbank - South Shields Millbank - South Shields 4 Gateshead Gateshead Gateshead Gateshead Gateshead Gateshead Gateshead Gateshead Gateshead Gateshead Gateshead Gateshead 5 Wallsend Wallsend Wallsend Wallsend relocated to Middle Engine Lane SOLD 6 Etal Lane Etal Lane Etal Lane Etal Lane Etal Lane Etal Lane Etal Lane Etal Lane Etal Lane Etal Lane Etal Lane Etal Lane 7 Market Street Market Street Market Street Market Street Market Street Market Street Market Street Market Street/Pilgrim street Relocated to Forth Banks SOLD 8 Bedlington Bedlington Bedlington Bedlington Bedlington Bedlington Bedlington Bedlington -

Royal Archaeological Institute / Roman Society Colloquium

Royal Archaeological Institute / Roman Society Colloquium The Romans in North-East England 29 November to 1 December 2019 Chancellor’s Hall, Senate House, Malet Street, University of London WC1E 7HU www.royalarchinst.org [email protected] Registered Charity Number 226222 Friday, 29 November 2019 18.00-18.30 Registration 18.30-19.30 Introduction: The Romans In North-East England (Martin Millett) 19.30-20.00 Discussion Saturday, 30 November 2019 9.30-10.00 Late registration/coffee 10.00-11.00 Aldborough (Rose Ferraby and Martin Millett) 11.00-12.00 Recent Work at Roman Corbridge (Ian Haynes, Alex Turner, Jon Allison, Frances McIntosh, Graeme Stobbs, Doug Carr and Lesley Davidson) 12.00-13.30 LUNCH 13.30-14.30 Scotch Corner (Dave Fell) 14.30-15.00 A684 Bedale Bypass: The excavation of a Late Iron Age/Early Roman Enclosure and a late Roman villa (James Gerrard) 15.00-15.30 COFFEE 15.30-16.30 Dere Street: York to Corbridge – a numismatic perspective (Richard Brickstock) 16.30-17.30 Panel Discussion (Lindsay Allason-Jones, Colin Haselgrove, Nick Hodgson and Pete Wilson) 17.30-19.00 RECEPTION Sunday, 1 December 2019 9.30-10.30 Bridge over troubled water? Ritual or rubbish at Roman Piercebridge (Hella Eckardt and Philippa Walton) 10.30-11.00 Cataractonium: Establishment, Consolidation and Retreat (Stuart Ross) 11.00-11.30 COFFEE www.royalarchinst.org [email protected] Registered Charity Number 226222 11.30-12.00 New light on Roman Binchester: Excavations 2009-17 (David Petts – to be read by Pete Wilson) 12.00-12.30 Petuaria Revisited -

THE RURAL ECONOMY of NORTH EAST of ENGLAND M Whitby Et Al

THE RURAL ECONOMY OF NORTH EAST OF ENGLAND M Whitby et al Centre for Rural Economy Research Report THE RURAL ECONOMY OF NORTH EAST ENGLAND Martin Whitby, Alan Townsend1 Matthew Gorton and David Parsisson With additional contributions by Mike Coombes2, David Charles2 and Paul Benneworth2 Edited by Philip Lowe December 1999 1 Department of Geography, University of Durham 2 Centre for Urban and Regional Development Studies, University of Newcastle upon Tyne Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Scope of the Study 1 1.2 The Regional Context 3 1.3 The Shape of the Report 8 2. THE NATURAL RESOURCES OF THE REGION 2.1 Land 9 2.2 Water Resources 11 2.3 Environment and Heritage 11 3. THE RURAL WORKFORCE 3.1 Long Term Trends in Employment 13 3.2 Recent Employment Trends 15 3.3 The Pattern of Labour Supply 18 3.4 Aggregate Output per Head 23 4 SOCIAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL DYNAMICS 4.1 Distribution of Employment by Gender and Employment Status 25 4.2 Differential Trends in the Remoter Areas and the Coalfield Districts 28 4.3 Commuting Patterns in the North East 29 5 BUSINESS PERFORMANCE AND INFRASTRUCTURE 5.1 Formation and Turnover of Firms 39 5.2 Inward investment 44 5.3 Business Development and Support 46 5.4 Developing infrastructure 49 5.5 Skills Gaps 53 6. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 55 References Appendices 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The scope of the study This report is on the rural economy of the North East of England1. It seeks to establish the major trends in rural employment and the pattern of labour supply. -

Northumberland County Council

Northumberland County Council Weekly List of Planning Applications Applications can view the document online at http://publicaccess.northumberland.gov.uk/online-applications If you wish to make any representation concerning an application, you can do so in writing to the above address or alternatively to [email protected]. Any comments should include a contact address. Any observations you do submit will be made available for public inspection when requested in accordance with the Access to Information Act 1985. If you have objected to a householder planning application, in the event of an appeal that proceeds by way of the expedited procedure, any representations that you made about the application will be passed to the Secretary of State as part of the appeal Application No: 21/00438/FUL Expected Decision: Delegated Decision Date Valid: Feb. 26, 2021 Applicant: Mr Steven Waite Agent: Mr Garry Phillipson Weardale House, Eastwood 12 Chestnut Avenue, Redcar Villas, West Wylam, Prudhoe, East, Redcar, Cleveland, TS10 Northumberland, NE42 5NQ, 3PB Proposal: Single storey rear extension to provide kitchen and sun room Location: Weardale House, Eastwood Villas, West Wylam, Prudhoe, Northumberland, NE42 5NQ, Neighbour Expiry Date: Feb. 26, 2021 Expiry Date: April 22, 2021 Case Officer: Miss Amber Windle Decision Level: Ward: Prudhoe South Parish: Prudhoe Application No: 21/00449/FUL Expected Decision: Delegated Decision Date Valid: Feb. 26, 2021 Applicant: Miss Shona Ferguson Agent: Estates Office, Alnwick Castle, Alnwick, NE66 1NQ, Proposal: Proposed demolition of the existing farmhouse and replacement with a 4-bedroom dwelling; demolition and change of use of detached outbuilding and replacement with a 3-bedroom and 2-bedroom dwelling; conversion of existing L-shaped outbuilding into 2no. -

Hugh Fearnall JP: CCSA Chairman Stable Cottage, Aydon, Corbridge

Patron: The Right Reverend Graeme Knowles CATHEDRAL & CHURCH SHOPS ASSOCIATION TRADE FAIR Wednesday 23rd September & Thursday 24th September 2015 Hexham Abbey, Beaumont Street, Hexham, Northumberland, NE46 3NB To whom it may concern. The CCSA "Cathedral & Church Shops Association” offers Managers/Staff of Cathedral & Church Shops encouragement and support helping them to promote and improve retailing in sacred places with over 150 Member Cathedral and Churches nationally. The "CCSA" holds regional meetings for training and support events during the year, also an Annual Conference and Trade Fair which enables Cathedrals and Churches with Shops/retail space to view and order stock at competitive prices with supplier discounts offered to CCSA members etc. This year we are holding our Annual Conference and Trade Fair at Hexham Abbey including the Annual Dinner in the new Great Hall at Hexham Abbey, over the 23rd & 24th September 2015. Hexham is centrally located between Newcastle Upon Tyne and Carlisle and well served by Road, Rail and Air, therefore we wanted to extend an invitation to you to come along to the Trade Fair on either days. You would be very welcome and we would be delighted if you can join us there. I appreciate if you would consider attending this years Trade Fair and didn't want you to miss out on this opportunity!. The “CCSA” is a non profit making Association, run by Volunteers who are all Retail Managers/Volunteers in Cathedral and Church Shops. It is FREE to attend the Trade Fair at Hexham Abbey. We offer you a complimentary tea or coffee on the day however if you wish to join us for lunch and/or Afternoon Tea there would be a charge of £10 per person to cover the catering cost on either day. -

Ad122-2016.Pdf

Connections 10 — Newcastle » Metrocentre » Blaydon » Ryton » Prudhoe » Corbridge » Hexham from Newcastle X85 — Newcastle » Benwell Grove » Denton Burn » Heddon-on-the-Wall » Horsley » Corbridge » Hexham Mondays to Fridays (except Public Holidays) Saturdays Sundays (including Public Holidays) Service number 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 Service number 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 Service number 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 Newcastle, Eldon Square 0650 0720 0820 0923 1025 1125 1325 1425 1525 Newcastle, Eldon Square 0700 0730 0830 0925 1025 1125 1325 1425 1525 Newcastle, Eldon Square 0800 0900 0952 1052 1252 1352 1452 Metrocentre 0708 0738 0838 0941 1043 1143 1343 1443 1543 Metrocentre 0716 0746 0846 0943 1043 1143 1343 1443 1543 Metrocentre 0816 0916 1010 1110 1310 1410 1510 Prudhoe Front Street, Co-operative 0737 0808 0909 1013 1115 1215 1415 1516 1617 Prudhoe Front Street, Co-operative 0741 0811 0911 1012 1115 1215 1415 1515 1615 Prudhoe Front Street, Co-operative 0842 0942 1040 1140 1340 1440 1540 Hexham Bus Station 0809 0840 0941 1045 1147 1247 1447 1548 1649 Hexham Bus Station 0810 0840 0940 1044 1147 1247 1447 1547 1647 Hexham Bus Station 0911 1011 1112 1212 1412 1512 1612 Service number X84 X85 X85 X85 X85 X85 X85 X85 X85 Service number X85 X85 X85 X85 X85 X85 X85 Sorry, no service on Sundays or Public Holidays for X84 and X85. Newcastle, Eldon Square 0725 0800 0910 1010 1110 1210 1410 1510 1610 Newcastle, Eldon Square 0910 1010 1110 1210 1410 1510 1610 Hexham Bus Station 0825 0847 0957 1057 1157 1257 1457 1557 1657 Hexham Bus Station 0957 1057 -

Northeast England – a History of Flash Flooding

Northeast England – A history of flash flooding Introduction The main outcome of this review is a description of the extent of flooding during the major flash floods that have occurred over the period from the mid seventeenth century mainly from intense rainfall (many major storms with high totals but prolonged rainfall or thaw of melting snow have been omitted). This is presented as a flood chronicle with a summary description of each event. Sources of Information Descriptive information is contained in newspaper reports, diaries and further back in time, from Quarter Sessions bridge accounts and ecclesiastical records. The initial source for this study has been from Land of Singing Waters –Rivers and Great floods of Northumbria by the author of this chronology. This is supplemented by material from a card index set up during the research for Land of Singing Waters but which was not used in the book. The information in this book has in turn been taken from a variety of sources including newspaper accounts. A further search through newspaper records has been carried out using the British Newspaper Archive. This is a searchable archive with respect to key words where all occurrences of these words can be viewed. The search can be restricted by newspaper, by county, by region or for the whole of the UK. The search can also be restricted by decade, year and month. The full newspaper archive for northeast England has been searched year by year for occurrences of the words ‘flood’ and ‘thunder’. It was considered that occurrences of these words would identify any floods which might result from heavy rainfall. -

Northumbria PCC Property Assets List December 2015

Asset List – Police and Crime Commissioner for Northumbria Status Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Address Line 3 Address Line 4 Address Line 5 Postcode Freehold Gillbridge Police Station Livingstone Road Sunderland Tyne & Wear SR1 3AW Leasehold Sunderland Central Police Sunderland Central Railway Row Sunderland Tyne & Wear SR1 3HE Office Community Fire Station Leasehold Proposed Sunderland Unit 7, Signal House Waterloo Place Sunderland Tyne & Wear SR1 3HT Central Neighbourhood Public Enquiry Office - Not yet open to the public Freehold Former Farringdon Hall Primate Road Sunderland Tyne & Wear SR3 1TQ Police Station – For Sale Leasehold Farringdon Neighbourhood Farringdon Community North Moor Road Sunderland Tyne & Wear SR3 1TJ Police Office Fire Station Freehold Southwick Police Station Church Bank Southwick Sunderland Tyne & Wear SR5 2DU Freehold Washington Police Station The Galleries Washington Tyne & Wear NE38 7RY Freehold Houghton Police Station Dairy Lane Houghton le Spring Sunderland Tyne & Wear DH4 5BH Freehold South Shields Police Station Millbank South Shields Tyne & Wear NE33 1RR Freehold Boldon Police Station North Road Boldon Colliery Tyne & Wear NE35 9AF Freehold Harton Police Station 187 Sunderland Road Harton South Shields Tyne & Wear NE34 6AQ Freehold Former Hebburn Police Victoria Road East Hebburn Tyne & Wear NE31 1XF Station – For Sale Leasehold Hebburn Police Office Hebburn Community Victoria Road Hebburn Tyne & Wear NE31 1UD Fire Station Leasehold Hebburn Neighbourhood Hebburn Central Rose Street Hebburn Tyne and