Ws9.!72~!2I~~~~'~M0frica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tendense En Tematologie in Populêre Werke Oor Suid- Afrikaanse Rugby, 1948-1995: ’N Historiografiese Studie

Tendense en tematologie in populêre werke oor Suid- Afrikaanse rugby, 1948-1995: ’n Historiografiese studie. Wouter de Wet Tesis voorgelê in ooreenkoms met die vereistes vir die graad MA (Geskiedenis) aan die Universiteit van Stellenbosch Studieleier: Prof. A.M. Grundlingh December 2013 [1] Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Verklaring: Ek, die ondergetekende, erken hiermee dat die werk wat in hierdie navorsing/verhandeling vervat is, my eie, oorspronklike werk is en dat ek dit voorheen nie in sy geheel, of gedeeltelik, by enige ander universiteit vir ’n graad ingehandig het nie. Handtekening: WJ de Wet Datum: 2 September 2013 Copyright © 2013 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved [2] Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Opsomming Hierdie studie is ’n historiografiese studie van populêre rugby geskiedskrywing, en dek die jare 1948 tot 1995. Die doel is om te dui op hoe dié sport in populêre skrywes uitgebeeld is. Die fokus gaan val op die twee vorme van populêre geskiedskrywing in hierdie tydperk, naamlik algemene rugbygeskiedenisboeke en biografiese werke. Die manier hoe hierdie verhandeling te werk gaan, is om tendense en tematologie in hierdie werke te identifiseer en die verandering daarvan oor die jare, na te volg. Hierdie werk lê op die breekvlak tussen ’n studie van die geskiedenis en die letterkunde. Deur die gewilde rugby skrywes inhoudelik en letterkundig in fyn detail te bestudeer, gaan lig op die veranderende tendense en tematologie gewerp word. Aanhalings word deurgans ingesluit en bespreek om die ontwikkeling van die populêre rugby geskiedskrywing oor die jare te verduidelik. Deur op hierdie kompleksiteite klem te lê, poog die studie om ’n bydrae te lewer tot die steeds ontwikkelende veld van Suid- Afrikaanse sportgeskiedenis. -

An Anthropological Study Into the Lives of Elite Athletes After Competitive Sport

After the triumph: an anthropological study into the lives of elite athletes after competitive sport Susanna Maria (Marizanne) Grundlingh Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements in respect of the Doctoral Degree in Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology in the Faculty of Humanities at the University of the Free State Supervisor: Professor Robert Gordon December 2015 DECLARATION I, Susanna Maria (Marizanne) Grundlingh, declare that the thesis that I herewith submit for the Doctoral Degree of Philosophy at the University of the Free State is my independent work, and that I have not previously submitted it for a qualification at another institution of higher education. I, Susanna Maria (Marizanne) Grundlingh, hereby declare that I am aware that the copyright is vested in the University of the Free State. I, Susanna Maria (Marizanne) Grundlingh, hereby declare that all royalties as regards intellectual property that was developed during the course of and/or in connection with the study at the University of the Free State, will accrue to the University. In the event of a written agreement between the University and the student, the written agreement must be submitted in lieu of the declaration by the student. I, Susanna Maria (Marizanne) Grundlingh, hereby declare that I am aware that the research may only be published with the dean’s approval. Signed: Date: December 2015 ii ABSTRACT The decision to retire from competitive sport is an inevitable aspect of any professional sportsperson’s career. This thesis explores the afterlife of former professional rugby players and athletes (road running and track) and is situated within the emerging sub-discipline of the anthropology of sport. -

The Long Shadow of the 1981 Springbok Tour of New Zealand and the United States of America

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stellenbosch University SUNScholar Repository “Barbed-Wire Boks”: The Long Shadow of the 1981 Springbok Tour of New Zealand and the United States of America by Sebastian Johann Shore Potgieter Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts and Social Sciences in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Albert Grundlingh March 2017 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2017 Copyright © 2017 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT In 1981, during the height of apartheid, the South African national rugby team, the Springboks, toured to New Zealand and the United States of America. In South Africa, the tour was expected to reopen the doors to international competition for the Springboks after an anti-apartheid sporting boycott had forced the sport into relative isolation during the 1970s. In the face of much international condemnation, the Springboks toured to New Zealand and the USA in 1981 where they encountered large and often violent demonstrations as those who opposed the tour attempted to scuttle it. -

Table of Contents

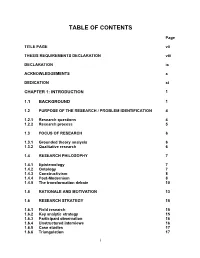

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TITLE PAGE vii THESIS REQUIREMENTS DECLARATION viii DECLARATION ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS x DEDICATION xi CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 BACKGROUND 1 1.2 PURPOSE OF THE RESEARCH / PROBLEM IDENTIFICATION 4 1.2.1 Research questions 4 1.2.2 Research process 5 1.3 FOCUS OF RESEARCH 6 1.3.1 Grounded theory analysis 6 1.3.2 Qualitative research 6 1.4 RESEARCH PHILOSOPHY 7 1.4.1 Epistemology 7 1.4.2 Ontology 7 1.4.3 Constructivism 8 1.4.4 Post-Modernism 8 1.4.5 The transformation debate 10 1.5 RATIONALE AND MOTIVATION 13 1.6 RESEARCH STRATEGY 15 1.6.1 Field research 15 1.6.2 Key analytic strategy 15 1.6.3 Participant observation 16 1.6.4 Unstructured interviews 16 1.6.5 Case studies 17 1.6.6 Triangulation 17 i 1.6.7 Purposive sampling 17 1.6.8 Data gathering and data analysis 18 1.6.9 Value of the research and potential outcomes 18 1.6.10 The researcher's background 19 1.6.11 Chapter layout 19 CHAPTER 2: CREATING CONTEXT: SPORT AND DEMOCRACY 21 2.1 INTRODUCTION 21 2.2 SPORT 21 2.2.1 Conceptual clarification 21 2.2.2 Background and historical perspective 26 2.2.2.1 Sport in ancient Rome 28 2.2.2.2 Sport and the English monarchy 28 2.2.2.3 Sport as an instrument of politics 29 2.2.3 Different viewpoints 30 2.2.4 Politics 32 2.2.5 A critical overview of the relationship between sport and politics 33 2.2.5.1 Democracy 35 (a) Defining democracy 35 (b) The confusing nature of democracy 38 (c) Reflection on democracy 39 2.3 CONCLUSION 40 CHAPTER 3: SPORT IN A GLOBAL CONTEXT 42 3.1 INTRODUCTION 42 3.2 A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE OF SPORT 43 -

Tracing the Development of Professionalism in South African

CONTENTS CONTENTS.................................................................................................................................................. 1 SUMMARY................................................................................................................................................... 3 OPSOMMING.............................................................................................................................................. 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................................................... 5 DEDICATION.............................................................................................................................................. 6 CHAPTER 1: ................................................................................................................................................ 7 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1. Problem Statement......................................................................................................................... 7 1.2. Literature Review......................................................................................................................... 10 CHAPTER 2: .............................................................................................................................................. 16 THE BEGINNING OF THE PROFESSIONAL -

Ÿþm Icrosoft W

18/81 NOTES AND DOCUMENTS* May 1981 18/81 NOTES AND DOCUMENTS* May 1981 REGISTER OF SPORTS CONTACTS WITH SOUTH AFRICA 1 September 1980 - 31 March 1981 Report by the Special Committee against Apartheid Note: This first register of sports contacts with South Africa contains an introduction on the significance of the campaign against apartheid sports, the reasons for the establishment of the register, and an appeal for action. The "register" itself contains three lists: (a) A list of sports exchanges with South Africa arranged by the code of sport; (b) A list of sportsmen and sportswomen who participated in sports events in South Africa, arranged by country; and (c) A list of promoters and administrators who have been active in collaboration with apartheid sport. It is intended that the register will be kept up-to-date and published from time to time. Names of persons who undertake not to engage in further sports contacts with South Africa will be deleted from future lists. The present publication was transmitted to the Organization of African Unity and made available at the International Conference on Sanctions against South Africa, held at UNESCO House, Paris, from 20 to 27 May 1981. *A#l material in these notes and documents may be freely reprinted. Ackncwiledot nt rtiether with a copy of the publication containing the reprint, would be appreciated. 81-14897 Introduction The Special Committee against Apartheid has for many years given special attention to the campaign for the boycott of anartheid sport in South Africa, as part of the international campaign against apartheid. -

Register of Sports Contacts with South Africa, 1 July - 31 December 1984

Register of Sports Contacts with South Africa, 1 July - 31 December 1984 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuun1985_05 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Register of Sports Contacts with South Africa, 1 July - 31 December 1984 Alternative title Notes and Documents - United Nations Centre Against ApartheidNo. 7/85 Author/Creator United Nations Centre against Apartheid Publisher United Nations, New York Date 1985-09-00 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1984 Source Northwestern University Libraries Description Pursuant to a decision in 1930, the Special Committee against Apartheid has been publishing semi-annual registers of sports contacts with South Africa. -

Masculine and Racial Identities of Black Rugby Players: a Study of a University Rugby Team

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Wits Institutional Repository on DSPACE Masculine and racial identities of black rugby players: A study of a university rugby team By Lungako C. Mweli 464905 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Witwatersrand Johannesburg 2015 1 Lungako Mweli 464905 University of the Witwatersrand DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I, LungakoMweli, hereby declare that this research report is my own original work. In the instances where the work of another person has been referenced or quoted, it has been cited and fully referenced according to the American Psychological Association (APA) format. I am fully aware of the implications of using plagiarised work in a project of this nature. ……………………………………. Lungako C Mweli ……………………………………. Date Department of Psychology University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg 2015 2 Lungako Mweli 464905 University of the Witwatersrand TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………….6 Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………...8 Chapter One ……………………………………………………………………………….9 1.1 Introduction and aim of the study……………………………………………………….9 1.2Rationale of the study………………………………………………………………….10 1.3 Conceptual framework…………………………………………………………………12 1.4The report structure…………………………………………………………………….13 Chapter Two: Literature review…………………………................................................14 2.1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………….14 2.2 Sport and race in -

Grundlingh Paper

UJ Sociology, Anthropology & Development Studies W E D N E S D A Y S E M I N A R Hosted by the Department of Sociology and the Department of Anthropology & Development Studies To be held at 15h30 on Wednesday, 10 August 2016, in C-Ring 315, UJ Kingsway campus Showcasing the Springboks: The Commercialisation of South African Rugby Heritage - Please do not copy or cite without authors’ permission - Dr. Marizanne Grundlingh Varsity College, Cape Town - Programme and other information online at www.uj.ac.za/sociology - 2 Showcasing the Springboks: The Commercialisation of South African Rugby Heritage Marizanne Grundlingh Introduction This paper is concerned with how sport museums, and in particular rugby museums, in South Africa tell the story of South Africa’s rich rugby heritage. By drawing on the author’s observations at the opening of the Springbok Experience Rugby Museum, making several visits to the museum, sourcing hitherto untapped archival sources from the South African Rugby Board archives, and conducting in-depth interviews with curators of private and commercial rugby museums in South Africa, this paper unpacks the sports heritage within broader heritage debates. It draws attention to the commercial nature of sport heritage initiatives, such as the Springbok Experience Museum. It is proposed that the professional turn in rugby in South Africa since the mid-1990s has made rugby heritage a viable commercial proposition, used not only tell the story of the country’s rugby past, but also to solidify the Springbok brand through the use of sport heritage modalities. More specifically the aim of this paper is to probe the politics of South African rugby heritage with reference to the complexity of representing black and coloured heritage at the Springbok Experience Rugby Museum. -

Swirling Shades of Gray by Permitting Some Integration in Sports, As in This Soccer Game in Soweto, South Africa Has Created an Illusion of Progress Where Little

May 16, 1983 Swirling Shades Of Gray By permitting some integration in sports, as in this soccer game in Soweto, South Africa has created an illusion of progress where little change exists The only way South Africa gets back into the Olympics is through the bush, with AK-47s. —A KENYAN DELEGATE TO THE SOCCER WORLD CUP, MADRID, 1982 Every time we clear the high jump, they put the pegs a notch higher. —A SOUTH AFRICAN CONSULAR OFFICIAL, NEW YORK CITY, 1983 Over the past 10 years, in newspapers throughout the U.S. and Western Europe, certain low- key advertisements have been appearing. Paid for by the South African government, they usually feature a bland message offering "information regarding progress and development in South Africa." A picture shows black and white athletes in competition together. It is captioned THE CHANGING FACE OF SOUTH AFRICA. If you respond to the invitation from the Minister (Information) of the South African Embassy in Washington, D.C., you might receive some South African government bulletins, such as No. 8/82, which is entitled Multiracial Sport Is Taken for Granted. This publication makes the claim, among others, that sport in South Africa is "multiracial" at all levels and that sports clubs are free to admit players and spectators "regardless of race, religion or politics." The clear inference is that the world is no longer justified in excluding South Africa from its great sporting occasions. For more than a quarter century South African sport has been one long, drawn-out war, at its ugliest internationally in the violent demonstrations that have taken place from Scotland to New Zealand. -

Divided We Stand! the Origins of Separation in South African Rugby

Divided We Stand! The Origins of Separation in South African Rugby. 1861-1899 by Colin du Plessis Submitted as requirement for the degree MAGISTERS HEREDITATIS CULTURAEQUE SCIENTAE (HISTORY) in the Faculty of Humanities University of Pretoria 2017 Supervisor: Prof. Karen L. Harris © University of Pretoria “…the history of the country is repeated in the history of sport…” H.P. Swaffer, 1914. © University of Pretoria Table of Contents List of Acronyms and Abbreviations i Acknowledgement ii Summary iii CHAPTER 1 THE DRESSING ROOM: INTRODUCTION 1 Sport and Division Social Identity Symbols, Rituals and Invented Traditions Cultural Hegemony Conclusion CHAPTER 2 THE PLAYING FIELD: LITERATURE OVERVIEW 16 Introduction General Histories Sports Specific Conclusion CHAPTER 3 WARM-UPS: A BRIEF HISTORY OF GAMES AND HUMANITY AT PLAY 36 Introduction Sport: unifier and divider The Historical Divide The Victorians and Modern Sport Sport and social control Conclusion CHAPTER 4 THE KICK OFF: BRITISH SCHOOLS, SPORT AND SOUTH AFRICA 65 Introduction The British at the Cape Education at the Cape The Cape, British Education and rugby Rugby Beyond the Cape Schools, Rugby and the Trekker Republics Conclusion © University of Pretoria CHAPTER 5 THE SECOND HALF: RUGBY BEYOND THE SCHOOLS 91 Introduction Cape Rugby Clubs The Transvaal Rugby Football Union as case study Conclusion CHAPTER 6 THE FINAL WHISTLE: EPILOGUE 109 SOURCES 119 Primary Sources Contemporary Literature Literature Magazines and Journal Articles Newspaper Articles Personal -

The Street Was Quiet, No Cars, No Children on Bicycles

Chapter 12 The time that David had spent in Britain had been good for him, but now that he was back in South Africa, he saw his homeland through new eyes. He was amazed at what lay in front of him. Here was rich material to fuel his songwriting. He was brimming with creativity. Everywhere he looked he saw or experienced something which inspired him. He began penning songs from a South African perspective. No more lyrics about the streets of London, or being down on his luck in Louisiana. David was no longer interested in writing and performing music that tried to emulate the American and British experiences. Instead, he threw himself into the vibrant tapestry of his South African lifestyle, the good and the bad. Songs such as “Bellville Blues”, “Signal Hill”, and so on, flowed from David’s pen. This new direction in David’s songwriting gave him the ammunition to talk about the life he was intimately familiar with, along with the possibility to speak of and for the unheard, the invisible everyday person of the South African platteland. A song such as “Montagu” was rooted in a place he knew, geographically and culturally. In this song he refers to the muscatel from the area, he speaks of the habit of the rural people often being curious about one’s family roots – who one is related to by birth or marriage. He also mentions the ubiquitous café found on the corner with its Coca Cola or Springbok tobacco advertising painted on the walls. In these songs David could mix a certain amount of romanticism in his subjects and temper it with political realism.