Spencerlawpoliti00spenrich.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

08-25 Grow Local

Orange County Review inSIDEr, August 25, 2011 in Some vegetable stands do not sell locally watermelons! Seriously, the Chinese are inject- Plant, till, harvest, sell, buy, eat grown produce. They buy it from wholesalers, ing watermelons with some sort of growth sub- and they are not listed in the guide. Wiley stance that makes some of them explode. You says, with these sellers, just ask; they'll tell you will not find one exploding watermelon at The where the produce comes from. And keep an Garden Patch. None of the pork coming out of SIDE eye out for dead giveaways, "products out of Retreat Farm is toxic. You will not get food poi- LOCAL season," such as tomatoes in April. soning from eating Tree and Leaf's leafy greens. There are a lot of enduring reasons to buy Are we self-sufficient locally? Molly Visosky We've seen the bumper fresh, buy local. One of them is travel distance. says we have the potential to be. She started stickers. We've opened our According to the Leopold Center for Sustainable the first locally grown gourmet produce distribu- mailbox to find the Buy Agriulture at Iowa State, locally produced food torship in this area three years ago, known as Fresh, Buy Local annual travels an average of 56 miles before it reaches Fresh Link. The name says it all. She's the link guide. New local pick-your- the consumer. Non locally produced food trav- between producers in Orange, Madison, and own outlets have sprouted els 1,494 miles or 27 times further. -

Publication and Depublication of California Court of Appeal Opinions: Is the Eraser Mightier Than the Pencil? Gerald F

Santa Clara Law Santa Clara Law Digital Commons Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 1-1-1992 Publication and Depublication of California Court of Appeal Opinions: Is the Eraser Mightier than the Pencil? Gerald F. Uelmen Santa Clara University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/facpubs Recommended Citation 26 Loy. L. A. L. Rev. 1007 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PUBLICATION AND DEPUBLICATION OF CALIFORNIA COURT OF APPEAL OPINIONS: IS THE ERASER MIGHTIER THAN THE PENCIL? Gerald F. Uelmen* What is a modem poet's fate? To write his thoughts upon a slate; The critic spits on what is done, Gives it a wipe-and all is gone.' I. INTRODUCTION During the first five years of the Lucas court,2 the California Supreme Court depublished3 586 opinions of the California Court of Ap- peal, declaring what the law of California was not.4 During the same five-year period, the California Supreme Court published a total of 555 of * Dean and Professor of Law, Santa Clara University School of Law. B.A., 1962, Loyola Marymount University; J.D., 1965, LL.M., 1966, Georgetown University Law Center. The author would like to acknowledge the assistance of Patrick Martucci, J.D., 1993, Santa Clara University School of Law, in the research for this Article. -

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

y f !, 2.(T I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings MAYA ANGELOU Level 6 Retold by Jacqueline Kehl Series Editors: Andy Hopkins and Jocelyn Potter Contents page Introduction V Chapter 1 Growing Up Black 1 Chapter 2 The Store 2 Chapter 3 Life in Stamps 9 Chapter 4 M omma 13 Chapter 5 A New Family 19 Chapter 6 Mr. Freeman 27 Chapter 7 Return to Stamps 38 Chapter 8 Two Women 40 Chapter 9 Friends 49 Chapter 10 Graduation 58 Chapter 11 California 63 Chapter 12 Education 71 Chapter 13 A Vacation 75 Chapter 14 San Francisco 87 Chapter 15 Maturity 93 Activities 100 / Introduction In Stamps, the segregation was so complete that most Black children didn’t really; absolutely know what whites looked like. We knew only that they were different, to be feared, and in that fear was included the hostility of the powerless against the powerful, the poor against the rich, the worker against the employer; and the poorly dressed against the well dressed. This is Stamps, a small town in Arkansas, in the United States, in the 1930s. The population is almost evenly divided between black and white and totally divided by where and how they live. As Maya Angelou says, there is very little contact between the two races. Their houses are in different parts of town and they go to different schools, colleges, stores, and places of entertainment. When they travel, they sit in separate parts of buses and trains. After the American Civil War (1861—65), slavery was ended in the defeated Southern states, and many changes were made by the national government to give black people more rights. -

Defining Music As an Emotional Catalyst Through a Sociological Study of Emotions, Gender and Culture

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 12-2011 All I Am: Defining Music as an Emotional Catalyst through a Sociological Study of Emotions, Gender and Culture Adrienne M. Trier-Bieniek Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Musicology Commons, Music Therapy Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Trier-Bieniek, Adrienne M., "All I Am: Defining Music as an Emotional Catalyst through a Sociological Study of Emotions, Gender and Culture" (2011). Dissertations. 328. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/328 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "ALL I AM": DEFINING MUSIC AS AN EMOTIONAL CATALYST THROUGH A SOCIOLOGICAL STUDY OF EMOTIONS, GENDER AND CULTURE. by Adrienne M. Trier-Bieniek A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology Advisor: Angela M. Moe, Ph.D. Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan April 2011 "ALL I AM": DEFINING MUSIC AS AN EMOTIONAL CATALYST THROUGH A SOCIOLOGICAL STUDY OF EMOTIONS, GENDER AND CULTURE Adrienne M. Trier-Bieniek, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2011 This dissertation, '"All I Am': Defining Music as an Emotional Catalyst through a Sociological Study of Emotions, Gender and Culture", is based in the sociology of emotions, gender and culture and guided by symbolic interactionist and feminist standpoint theory. -

Spring 2016 Issue

palaver e /p ‘læve r/ n. A talk, a discussion, a dialogue; (spec. in early use) a conference between African tribes-people and traders or travellers. v. To praise over-highly, flatter; to cajole. To persuade (a person) to do something; to talk (a person) out of or into something; to win (a per- son) over with palaver. To hold a colloquy or conference; to parley or converse with. © Palaver. Spring 2016 issue. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without prior written permission from Palaver. Rights to individual submissions remain the property of their authors. Graduate Liberal Studies Program University of North Carolina Wilmington 105 Bear Hall Wilmington, NC 28403 www.uncw.edu/gls Masthead | Spring 2016 Founding Editors Copy Chiefs Contributing Editors Sarah E. Bode John Dailey Dr. Josh Bell Ashley Elizabeth Hudson Mikkel Lysne Michelle Bliss Melissa Slaven-Warren Sarah E. Bode Executive Editor Dr. Theodore Burgh Patricia Turrisi Staff Lauren B. Evans Holli Terrell-Cavalluzi Dr. Carole Fink Editor-in-Chief Jonny Harris Courtney Johnson Ashley Elizabeth Hudson Travis Henry Katja Huru Linda McCormack Rebecca Lee Managing Editor Janay Moore Johannes Lichtman Erin Ball Dr. Marlon Moore Dr. Diana Pasulka Layout Editors Dr. Alex Porco Ashley Elizabeth Hudson Nick Rymer Erin Ball Dr. Michelle Scatton-Tessier Dr. Anthony Snider Layout Assistant Erin Sroka Gabe Reich Dr. Patricia Turrisi Cover Art: “The Indistinct Notion of an Object Trajectory” by Ryota Matsumoto Back Cover Art: “Surviving in the Multidimensional Space of Cognitive Dissonance” by Ryota Matsumoto Thank you to the Graduate Liberal Studies Program at UNCW for letting us call you home. -

Haack, Ernest Herman - Ed./Publ

Index to Rowland Cards. Transcribed by Joan Gilbert Martin & Stanley D. Stevens 333 Containing references to Santa Cruz County, California, Events, People, Subjects H in 1900 B-2 451; President, Musicians Union, 1907 B-2 526 Haack, Ernest Herman - ed./publ. Hagan, Albert (Judge) A-3 730; A-6 Watsonville Weekly Register, 399; B-1 1026.02, 1027.01, 1910; (post master) - sold 1033.03-1033.04; Elected Santa Watsonville Weekly Register to F. Cruz County Judge, 1867 B-2 98; W. Atkinson B-2 731; Watsonville Recording Sec., Library Assn., B-3 1211 1868 B-2 402; Railroad Bonds Haas, Alexander (Hass) B-1 346-347 Committee B-3 34; Suffragettes B- Haas, F. A. - Road District #3, 1852 3 1252; C-226 List of Land Owners B-2 6.1 Hagar, Lettie (Mrs. Brown) A-1 863 Haberdashers A-1 331.02 Hagemann (Mrs) - Elks Club B-3 808 Hackett Building, Boulder Creek B-1 Hagemann Avenue - Parsons, Henry 639.03-639.04 Fell A-5 52.02 Hackett, G. D. A-3 728 Hagemann Hotel A-4 348; built 1892 Hackett, George A-2 26; A-3 728; B-1 B-2 353 1021.03; Sons of Temperance B-3 Hagemann-McPherson - cost 969.05; C-235 $50,000, 1910 B-2 918 Hackett, George W. C-226 Hagemann, Adolph A-3 731.02 Hackett, Helen E. (Mrs. John S. Hagemann, Adolph F. - Santa Cruz Hodge) (Mrs. John S. Hunter) A-3 High School B-3 526.10 728, 1053, 1205 Hagemann, Amelia (Mrs.) A-3 Hackett, L. -

Hastings Community (Summer 1990) Hastings College of the Law Alumni Association

UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Hastings Alumni Publications 6-1-1990 Hastings Community (Summer 1990) Hastings College of the Law Alumni Association Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/alumni_mag Recommended Citation Hastings College of the Law Alumni Association, "Hastings Community (Summer 1990)" (1990). Hastings Alumni Publications. 76. http://repository.uchastings.edu/alumni_mag/76 This is brought to you for free and open access by UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Alumni Publications by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. ... ............ ....... ...::::.:.... .. .. ............ .................. .......... ............... ...... I.. ..... .................... ...... .... .......- ...... -.. ....-.................. ............... .. ..................... .......... ............ .. _ - ... I ... 1 I .............- . I.. I - I., mm . .. .............- .. - ................. .........- ...................... I..-..- .- . ............. ............ ... .. ..... 080188,mol:. I I .. '...., ........-. - - .............:, I I... I ...... ............,... , I ..I ....... ............ ...... .. .. .. somagamNSONNOBOW ..-I ................ ......... ... .....I . I .. I . .................. - X........... ., .-.... I ...... - SOONER=. I ..................-........... I I .......I .. ......... .. .... I . ....... :. : :. .... ........ .. 8 :." ... * ... -.. V..*. ......... I .::....... .., ... .......................'....... -

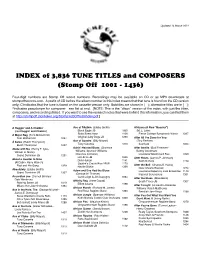

Clean” Version of the Index, with Just the Titles, Composers, and Recordings Listed

Updated 14 March 2021 INDEX of 3,836 TUNE TITLES and COMPOSERS (Stomp Off 1001 - 1436) Four-digit numbers are Stomp Off record numbers. Recordings may be available on CD or as MP3 downloads at stompoffrecords.com. A prefix of CD before the album number in this index means that that tune is found on the CD version only; C indicates that the tune is found on the cassette version only. Subtitles are shown in ( ); alternative titles are in [ ]; *indicates pseudonym for composer—see list at end. [NOTE: This is the “clean” version of the index, with just the titles, composers, and recordings listed. If you want to see the research notes that were behind this information, you can find them at http://stompoff.dickbaker.org/Stomp%20Off%20Index.pdf.] A Huggin’ and A Chalkin’ Ace of Rhythm (Jabbo Smith) Africana (A New “Booster”) (see Huggin’ and Chalkin’) Black Eagle JB 1065 (M. L. Lake) State Street Aces 1106 Pierce College Symphonic Winds 1297 A Major Rag (Tom McDermott) Original Salty Dogs JB 1233 Tom McDermott 1024 After All I’ve Done for You Ace of Spades (Billy Mayerl) (Tiny Parham) Á Solas (Butch Thompson) Tony Caramia 1313 Scaniazz 1004 Butch Thompson 1037 Achin’ Hearted Blues (Clarence After Awhile (Bud Freeman– Abide with Me (Henry F. Lyte– Williams–Spencer Williams– Benny Goodman) William H. Monk) Clarence Johnson) Louisiana Washboard Five 1398 Grand Dominion JB 1291 Hot Antic JB 1099 After Hours (James P. Johnson) About a Quarter to Nine Dick Hyman 1141 Keith Nichols 1159 (Al Dubin–Harry Warren) Gauthé’s Creole Rice YBJB 1170 After the Ball (Charles K. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Kathryn A. Stebner, State Bar No. 121088 Sarah Colby

Case3:13-cv-03962-SC Document103 Filed07/20/15 Page1 of 31 1 Kathryn A. Stebner, State Bar No. 121088 Guy B. Wallace, State Bar No. 176151 Sarah Colby, State Bar No. 194475 Mark T. Johnson, State Bar No. 76904 2 George Kawamoto, State Bar No. 280358 Jennifer Uhrowczik, State Bar No. 302212 STEBNER AND ASSOCIATES SCHNEIDER WALLACE COTTRELL 3 870 Market Street, Suite 1212 KONECKY WOTKYNS, LLP San Francisco, CA 94102 2000 Powell Street, Suite 1400 4 Tel: (415) 362-9800 Emeryville, California 94608 Fax: (415) 362-9801 Tel: (415) 421-7100 5 Fax: (415) 421-7105 6 Michael D. Thamer, State Bar No. 101440 W. Timothy Needham, State Bar No. 96542 LAW OFFICES OF MICHAEL D. THAMER JANSSEN MALLOY LLP 7 Old Callahan School House 730 Fifth Street 12444 South Highway 3 Eureka, CA 95501 8 Post Office Box 1568 Tel: (707) 445-2071 Callahan, California 96014-1568 Fax: (707) 445-8305 9 Tel: (530) 467-5307 Fax: (530) 467-5437 10 Robert S. Arns, State Bar No. 65071 Christopher J. Healey, State Bar. No. 105798 11 THE ARNS LAW FIRM DENTONS US LLP 515 Folsom Street, 3rd Floor 600 West Broadway, Suite 2600 12 San Francisco, CA 94105 San Diego, CA 92101-3372 Tel: (415) 495-7800 Tel: (619) 235-3491 13 Fax: (415) 495-7888 Fax: (619) 645-5328 14 Attorneys for Plaintiffs and the proposed Class 15 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 16 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 17 SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION 18 Arville Winans, by and through his CASE NO. 3:13-cv-03962-SC Guardian ad litem, Renee Moulton, on his 19 own behalf and on behalf of others NOTICE OF MOTION AND MOTION FOR similarly situated, ATTORNEYS’ FEES, COSTS, AND 20 SERVICE AWARDS; MEMORANDUM OF Plaintiff, POINTS AND AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT 21 OF PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR vs. -

6Th Annual Martz Winter Symposium

for Natural Resources, Energy, and the Environment at Colorado Law 6th Annual Martz Winter Symposium The Changing Landscape of Public Lands Thursday, February 28th and Friday, March 1st, 2019 Wolf Law Building, Wittemyer Courtroom University of Colorado School of Law 6th Annual Martz Symposium Clyde O. Martz was a father of natural resource law in the United States. He was an exemplary teacher, mentor, counselor, advocate, and a professor of natural resources law for 15 years at Colorado Law. Professor Martz was one of the founders of the Rocky Mountain Mineral Law Foundation and of the Law School’s Natural Resources Law Center, which later became the Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural Resources, Energy, and the Environment. In 1951, he assembled and published the first natural resources law casebook, combining the previously discrete subjects of water law, mining law, and oil and gas law. In 1962, Professor Martz joined the law firm of Davis Graham & Stubbs. During his tenure at Davis, Graham & Stubbs, he took periodic leaves of absence to serve as the Assistant Attorney General of the Lands and Natural Resources Division of the U.S. Department of Justice (1967- 69), a Colorado Special Assistant Attorney General (1971-75), and as the Solicitor of the Department of the Interior (1980-81). He retired from the firm in the late 1990s and passed away in 2010 at the age of 89. The Martz Natural Resources Management Fund was established in memory of natural resources law pioneer Clyde Martz and supports innovative programming at Colorado Law on best practices in natural resources management. -

California Groundwater Law, San Fancisco, CA

Thursday, May 18, 2017 UC Hastings-College of Law, 198 McAllister Street, San Francisco, CA 94102 This program qualifies for 6.5 CA MCLE Credits Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck LLP is the approved MCLE sponsor provider for this conference by the State Bar of California. EVENT SPONSORS An American Ground Water Trust Conference The American Ground Water Trust’s annual California Groundwater Law Conference is back in San Francisco for 2017. Attendees will hear from a cadre of high caliber presenters and will gain insight about legal strategies regarding aquifer contamination litigation and hear perspectives about solving legal issues related to California’s water management challenges. This annual update on California’s groundwater law is typically attended by attorneys, water utility and water district staff, City/County staff and Commissioners, State and Federal regulators, growers, irrigation districts, water engineers and consultants, academics, environmental NGOs and those interested in legal issues affecting California’s groundwater- rights, management, ownership, protection and use. CONFERENCE AGENDA 8:30 – 8:40 INTRODUCTION: CONFERENCE OBJECTIVES Andrew Stone, Executive Director, American Ground Water Trust, Concord, NH 8:40 – 9:10 CURRENT GROUNDWATER LAW CONTROVERSIES IN CALIFORNIA David Owen, Professor of Law, University of California, Hastings College of Law, San Francisco, CA 9:10 – 10:30 Session 1 GROUNDWATER SUSTAINABILITY PLANS: POTENTIAL CHALLENGES AND SOLUTIONS Session moderator - Deb Kollars, Attorney, Best Best & Krieger, Sacramento, CA Session description and background: This Session describes key areas where legal conflicts could arise in the preparation and implementation of GSPs, including potential water rights conflicts. Decision support modeling naturally supports a collaborative approach to determine a sustainable management plan for the basin. -

Publication and Depublication of California Court of Appeal Opinions: Is the Eraser Mightier Than the Pencil

Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review Volume 26 Number 4 Symposium on the California Judiciary and The Second Annual Fritz B. Burns Article 7 Lecture on the Constitutional Dimensions of Property: The Debate Continues 6-1-1993 Publication and Depublication of California Court of Appeal Opinions: Is the Eraser Mightier Than the Pencil Gerald F. Uelmen Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Gerald F. Uelmen, Publication and Depublication of California Court of Appeal Opinions: Is the Eraser Mightier Than the Pencil, 26 Loy. L.A. L. Rev. 1007 (1993). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr/vol26/iss4/7 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PUBLICATION AND DEPUBLICATION OF CALIFORNIA COURT OF APPEAL OPINIONS: IS THE ERASER MIGHTIER THAN THE PENCIL? Gerald F. Uelmen* What is a modem poet's fate? To write his thoughts upon a slate; The critic spits on what is done, Gives it a wipe-and all is gone.' I. INTRODUCTION During the first five years of the Lucas court,2 the California Supreme Court depublished3 586 opinions of the California Court of Ap- peal, declaring what the law of California was not.4 During the same five-year period, the California Supreme Court published a total of 555 of * Dean and Professor of Law, Santa Clara University School of Law.