Methods and Experiments for Sensing Variations in Solar Activity and Defining Their Impact on Heart Variability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is Rf? It's Like Magic

Originally appeared in the December 2011 issue of Communications Technology. WHAT IS RF? IT’S LIKE MAGIC By RON HRANAC The cable industry has, since the very first systems in the late 1940s, embraced and been based on radio frequency (RF) technology. These days, we’ve also embraced the digital world — and a subset of digital technology called Internet protocol (IP) — but RF still is needed in most cable networks to transport digital data to and from devices in our subscribers’ homes. The answer to the question in the title of this month’s column is far more complicated than it seems initially. A good place to start is with an explanation of “R” and “F.” What’s radio frequency? Here’s one high-level perspective: It’s that portion of the electromagnetic spectrum from a few kilohertz to about 300 gigahertz. The radio-frequency part of the electromagnetic spectrum is further broken down into two chunks: radio waves and microwaves. Some references define radio waves as those with a frequency starting at about 3 kHz (the beginning of the very low frequency [VLF] band) and extending to 300 MHz (the beginning of the ultra high frequency [UHF] band), with microwaves covering roughly 300 MHz to 300 GHz. The latter is the beginning of the far infrared (FIR) portion of the electromagnetic spectrum. Other references have microwaves starting at frequencies higher than 300 MHz; indeed, many RF engineers consider the microwave spectrum to be higher than about 1 GHz. Radio frequency also can be defined as a rate of oscillation within the 3 kHz to 300 GHz range (more on this in a moment). -

A Novel Database of Bio-Effects from Non-Ionizing Radiation

A Novel Database of Bio-Effects From Non-Ionizing Radiation by Leach VA, Weller S and Redmayne M. ORSAA paper ID: 3088 OPEN SOURCE: https://www.degruyter.com/view/journals/reveh/33/3/article-p273.xml Rev Environ Health 2018; aop Review Victor Leach*, Steven Weller and Mary Redmayne A novel database of bio-effects from non-ionizing radiation https://doi.org/10.1515/reveh-2018-0017 Received March 18, 2018; accepted May 6, 2018 Introduction Abstract: A significant amount of electromagnetic field/ The environmental profile of man-made electromagnetic electromagnetic radiation (EMF/EMR) research is availa- field (EMF) and associated radiation [electromagnetic ble that examines biological and disease associated end- radiation (EMR)] over the last several decades has grown points. The quantity, variety and changing parameters in by 12 orders of magnitude (1012) [1] and is now considered the available research can be challenging when under- one of the major sources of environmental pollution. taking a literature review, meta-analysis, preparing a During more recent years, the use of mobile phones study design, building reference lists or comparing find- in close proximity to the brain has become a major focus ings between relevant scientific papers. The Oceania of much research. Successful marketing and subsequent Radiofrequency Scientific Advisory Association (ORSAA) uptake have necessitated an on-going increase in the has created a comprehensive, non-biased, multi-cate- number of mobile phone base stations being deployed, gorized, searchable database of papers on non-ionizing contributing to increasing levels of background, environ- EMF/EMR to help address these challenges. It is regu- mental non-ionizing radiation. -

Principes Et Utilisations RF Power Sources: Principles And

Alimentations RF: Principes et utilisations RF Power Sources: Principles and Use Erik V. Johnson LPICM-CNRS, Ecole Polytechnique Erik V. Johnson, 1 LPICM-CNRS, Ecole Polytechnique Erik V. Johnson, LPICM-CNRS, Ecole Polytechnique Erik V. Johnson, LPICM-CNRS, Ecole Polytechnique Erik V. Johnson, LPICM-CNRS, Ecole Polytechnique Erik V. Johnson, LPICM-CNRS, Ecole Polytechnique Erik V. Johnson, LPICM-CNRS, Ecole Polytechnique Erik V. Johnson, LPICM-CNRS, Ecole Polytechnique Erik V. Johnson, LPICM-CNRS, Ecole Polytechnique Erik V. Johnson, LPICM-CNRS, Ecole Polytechnique Outline – RF Power Sources • Frequencies of operation • ITU/STM Frequency bands for RF plasmas • Amplifiers vs Power Sources • Input and Output Power • Expected impedance and matching • Gain compression • Harmonics (THD and dBc) • Classes of Amplifier • Class A – Wideband amplifier • Classes B to E – Narrow band Erik V. Johnson, LPICM-CNRS, Ecole Polytechnique What do we mean by RF plasma excitation Technically, all frequencies at which we can generate EM waves through oscillations in a macroscopic dipole/antenna are radio frequencies. Direct current (0 Hz) does not generate an EM wave, and optical frequency waves are not generated in the same way (and physics is different). For plasmas, we are particularly interested in the band of frequencies where electrons can respond but ions are too heavy, and things are still technologically manageable. Erik V. Johnson, LPICM-CNRS, Ecole Polytechnique Radio Frequencies and ISM Bands International Telecommunications Union has split up spectrum into named bands. Frequencies of 1 GHz and above are conventionally called microwave,[7] while frequencies of 30 GHz and above are designated millimeter wave. Erik V. Johnson, LPICM-CNRS, Ecole Polytechnique ITU Band name Abbrev. -

Frequency Multiplication in Silicon Nanowires

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Summer 7-7-2016 Frequency Multiplication in Silicon Nanowires Marius Mugurel Ghita Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Nanoscience and Nanotechnology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ghita, Marius Mugurel, "Frequency Multiplication in Silicon Nanowires" (2016). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3082. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.3077 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Frequency Multiplication in Silicon Nanowires by Marius Mugurel Ghita A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Applied Physics Dissertation Committee: Raj Solanki, Chair James Morris John Freeouf Andrew Rice Portland State University 2016 ABSTRACT Frequency multiplication is an effect that arises in electronic components that exhibit a non-linear response to electromagnetic stimuli. Barriers to achieving very high frequency response from electronic devices are the device capacitance and other parasitic effects such as resistances that arise from the device geometry and are in general a function of the size of the device. In general, smaller device geometries and features lead to a faster response to electromagnetic stimuli. It was posited that the small size of the silicon nanowires (SiNWs) would lead to small device capacitance and spreading resistance, thus making the silicon nanowires useful in generating microwave and terahertz radiation by frequency multiplication. -

Mathematical Analysis of Super Low Frequency Ground Loop Receiving Antennas

Appl. Math. Inf. Sci. 7, No. 3, 1087-1092 (2013) 1087 Applied Mathematics & Information Sciences An International Journal ⃝c 2013 NSP Natural Sciences Publishing Cor. Mathematical Analysis of Super Low Frequency Ground Loop Receiving Antennas Hui Xie1, Ming Yang2 and Long Ji3 1Electronics Engineering College, Navy University of engineering, Wuhan 430033, China 2Unit 91404 of PLA, Qinhuangdao 066000, China 3702 repair factory of Navy, Shanghai 200434, China Received: 20 Sep. 2012, Revised: 30 Dec. 2012, Accepted: 14 Jan. 2013 Published online: 1 May 2013 Abstract: A compact super low frequency receiving antenna in the form of a loop can be built for which the induced atmospheric noise voltage dominates both the antennas thermal noise voltage and preamplifier noise. Air-core and ferromagnetic-core ground loop receiving antennas were introduced, and mathematical calculation methods to analyse the ENF spectrum of the atmospheric noise and thermal noise were derived. The research identified the roles played by the various contributing factors such as antenna dimensions, wire conductivity, ferromagnetic-core permeability, etc. One air-core and three ferromagnetic-core antennas were designed, and a compromise core design was recommend, which takes advantage of the improvement that ferromagnetic cores can provide while largely avoiding the disadvantages. Keywords: super low frequency, loop receiving antenna, air-core loop, ferromagnetic core loop 1. Introduction factor of self-resonance may increase the output signal voltage, this is more than offset by a concomitant increase The two most conventional super low frequency (SLF) in the resistance of the antenna [4]. Usually, therefore, at receiving antennas are the whip and the loop. -

The Electromagnetic Spectrum Presentation

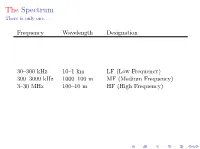

3{30 Hz 100{10 Mm ELF (Extra Low Frequency) 30{300 Hz 10{1 Mm SLF (Super Low Frequency) 300{3000 Hz 1 Mm{100 km ULF (Ultra Low Frequency) 3{30 kHz 100{10 km VLF (Very Low Frequency) 30{300 MHz 10{1 m VHF (Very High Frequency) 300{3000 MHz 1000{100 mm UHF (Ultra High Frequency) 3{30 GHz 100{10 mm SHF (Super High Frequency) 30{300 GHz 10{1 mm EHF (Extra High Frequency) 300{3000 GHz 1000{100µm Submillimeter/InfraRed 500{900 THz 0.6µm{0.3µm Visible! The Spectrum There is only one. Frequency Wavelength Designation 30{300 kHz 10{1 km LF (Low Frequency) 300{3000 kHz 1000{100 m MF (Medium Frequency) 3{30 MHz 100{10 m HF (High Frequency) 3{30 Hz 100{10 Mm ELF (Extra Low Frequency) 30{300 Hz 10{1 Mm SLF (Super Low Frequency) 300{3000 Hz 1 Mm{100 km ULF (Ultra Low Frequency) 300{3000 MHz 1000{100 mm UHF (Ultra High Frequency) 3{30 GHz 100{10 mm SHF (Super High Frequency) 30{300 GHz 10{1 mm EHF (Extra High Frequency) 300{3000 GHz 1000{100µm Submillimeter/InfraRed 500{900 THz 0.6µm{0.3µm Visible! The Spectrum There is only one. Frequency Wavelength Designation 3{30 kHz 100{10 km VLF (Very Low Frequency) 30{300 kHz 10{1 km LF (Low Frequency) 300{3000 kHz 1000{100 m MF (Medium Frequency) 3{30 MHz 100{10 m HF (High Frequency) 30{300 MHz 10{1 m VHF (Very High Frequency) 3{30 Hz 100{10 Mm ELF (Extra Low Frequency) 30{300 Hz 10{1 Mm SLF (Super Low Frequency) 3{30 GHz 100{10 mm SHF (Super High Frequency) 30{300 GHz 10{1 mm EHF (Extra High Frequency) 300{3000 GHz 1000{100µm Submillimeter/InfraRed 500{900 THz 0.6µm{0.3µm Visible! The Spectrum There is only one. -

Radiotherapy Is the Second Method for Treating Cancer (Through Ionizing Radiations)

Cancer Radiotherapy Radiotherapy is the second method for treating cancer (through ionizing radiations) •External radiotherapy : irradiation source is situated outside the patient (RX devices, cobalt, accelerators), •Brachytherapy : radioactive sources are situated inside the patient * sealed sources : ‐intersticial brachytherapy : sources placed inside the tumour ‐ endocavitary brachytherapy : sources inside natural cavities where tumours develop * non sealed sources: ‐radioactive compounds are injected for particular tumours : I 131, P32, St189, .. In France, radiotherapy is used for the treatment of one out of two cancer patients. Half of the patients who are cured of their cancer, are treated by radiotherapy Some historical data on radiotherapy 1895: Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen in Würzburg ((y)Germany) discovers X‐rays. 1895: First therapeutic attempt to treat a local relapse of breast carcinoma by Emil Grubbe (Chicago) 1896: Discovery of natural radioactivity by Henri Becquerel in Paris 1896: First use of X‐Rays for stomach cancer by Victor Despeignes (Lyon ‐ France) 1896: Irradiation of a skin tumour in a 4‐year‐old by Léopold Freund (Vienna ‐ Austria) 1897: Thomson identifies the electrons for creating X‐Rays 1898: Discovery of radium by Pierre Curie and Maria Sklodowska Curie in Paris 1899: First real proof of cure by X ‐Rays ( two pictures taken at an interval of 30 years) 1901:First thiherapeuticuseof radium for skin 'bhhbrachytherapy' byDrDanlos (ôi(Hôpita l Saint‐Louis ‐ Paris) 1903: First scientific description of the effect of -

Application Notes

APPLICATION NOTES GENERAL SPECIFICATIONS INSULATION RESISTANCE: Resistance greater than 2 Giga-ohms at 50 Vdc is required between the chassis and all switch terminals. SPECIAL TESTING: Is available upon request. Please contact factory. FINISH: Electroless Nickel, Contact Factory if different finish is required. RF CONTACTS: Beryllium Copper, Gold plated over a Nickel undercoating. STORAGE TEMPERATURE: -55°C to +100°C. TOLERANCES: Unless otherwise specified. Dimensions are in inches. XX: +/- 0.03 XXX: +/- 0.005 ANG: +/- 1° INTERNAL TERMINATION RF POWER: 3WCW @ +85°C INTERNAL TERMINATION VSWR: 2.00 VSWR max. typical. REPEATABILITY: 0.1 dB max. between positions. AUXILIARY CONTACTS: (Indicators) rated at 250mA, 100 Vdc, 5W max. (switching). Must use a series current limiting resistor. RF CONNECTOR TORQUE: Apply no more than 8 inch pounds of torque to install mating connectors. SUPPLY VOLTAGE: +/- 10% nominal. MAGNETIC SENSITIVITY: SPDT switches - electromechanical switches can be sensitive to ferrous materials and external magnetic fields. Allow mounting no closer than 1/8” for neighboring ferrous materials. ACTUATION: DTI Microwave switches are RF devices, the impedance match is lost if more than one position is actuated simultaneously. Simultaneous actuation of more than one position is not recommended and under certain circumstances may damage the switch. Please consult factory. DC TERMINAL FUNCTION LEGEND N/A Not Applicable AV Actuation Voltage C Actuation Voltage Common, Plus (+) or Minus (-) +V SW Positive Switch Actuation Voltage C RTN Common Return for Actuation & Logic Voltage Supplies L Logic Input (1= 3.5 - 5.5 Vdc; 0= 0 - 0.8 Vdc) PV Pulse Voltage with specified polarity for latching operation (20 msec min.) IND COM Indicator Common F/S Failsafe Position (when applicable) +1, -2 SPDT/Transfer Failsafe version, indicates positive & negative actuation terminals N/C Normally Closed Position N/O Normally Open Position +A TTL Control, Indicates Postive Coil Voltage Terminals -B TTL Control, Indicates DC Return SPECIFICATIONS SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE. -

Inexpensive Equipment and Simple Technique Changes

Inexpensive Equipment and Simple Technique Changes Paul Robertson - GCSAR Paul Robertson 4th Year on Team GCSAR Board of Directors SAR Academy Coordinator Field Director Ham Technician License – KE0ETR Paul Robertson - GCSAR Paul Robertson - GCSAR On Sunday, May 17, 2015 - Grand County Search and Rescue and Alpine Rescue helped 59-year-old Littleton resident, Brad Bylund, off of Mount Flora above Berthoud Pass. – SkyHigh Daily News Paul Robertson - GCSAR Growing membership required new radios Can we save money? Is there newer/better equipment Difficulty in Backcountry Radio Communication “SAR Repeater doesn’t work here” “Simplex won’t go up the canyon, over the peak” Paul Robertson - GCSAR How can we solve them: While purchasing new equipment With modification of equipment, techniques or protocols Paul Robertson - GCSAR Radio Waves Frequency Bandwidth Wavelength Power Hand held - 5 watts Mobile - 50 Watts Antennas Paul Robertson - GCSAR Paul Robertson - GCSAR [5] Frequency Wavelength Designation Abbreviation 5 4 3–30 Hz 10 –10 km Extremely low frequency ELF 4 3 30–300 Hz 10 –10 km Super low frequency SLF 3 300–3000 Hz 10 –100 km Ultra low frequency ULF 3–30 kHz 100–10 km Very low frequency VLF 30–300 kHz 10–1 km Low frequency LF 300 kHz – 3 MHz 1 km – 100 m Medium frequency MF 3–30 MHz 100–10 m High frequency HF 30–300 MHz 10–1 m Very high frequency VHF 300 MHz – 3 GHz 1 m – 10 cm Ultra high frequency UHF 3–30 GHz 10–1 cm Super high frequency SHF 30–300 GHz 1 cm – 1 mm Extremely high frequency EHF 300 GHz – 3000 GHz 1 mm – 0.1 mm Tremendously -

Waves, Wavelength, Frequency and Bands

1 2 Wave - A wave is a traveling disturbance that moves through space and matter. Waves transfer energy from one place to another, but not matter. Amplitude - The measure of the displacement of the wave from its rest position. The higher the amplitude of a wave, the higher its energy. Crest - The crest is the highest point of a wave. The opposite of the crest is the trough. Frequency - The frequency of a wave is the number of times per second that a wave cycles. The frequency is the inverse of the period. Wavelength - The wavelength of a wave is the distance between two corresponding points on back-to-back cycles of a wave. For example, between two crests of a wave. Trough - The trough is the lowest part of the wave. The opposite of the trough is the crest. Wave frequency is the number of waves that pass a fixed point in a given amount of time. The SI unit for wave frequency is the hertz (Hz), where 1 hertz equals 1 wave passing a fixed point in 1 second. Frequency • Unit of measurement is the Hertz. • Abbreviation is Hz. • One Hertz = 1 cycle per second. • Example: 500 waves pass a point in 2 seconds. What is the frequency? – 500 cycles/2 seconds = 250 Hz FREQUENCY The number of crests that pass a given point within one second is described as the frequency of the wave. One wave—or cycle—per second is called a Hertz (Hz), after Heinrich Hertz who established the existence of radio waves. A wave with two cycles that pass a point in one second has a frequency of 2 Hz. -

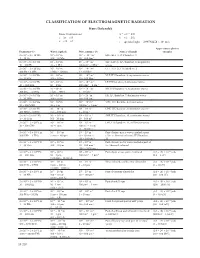

Classification of Electromagnetic Radiation Hans Dolezalek Basic Conversions: Λ = C/Ν = 1/K C = Λν = Ν/K K = Ν/C = 1/Λ Ν = C/Λ = Ck C = Speed of Light = 2 99792458

ClAssIFICATION OF ElECTROMAGNETIC RADIATION Hans Dolezalek Basic Conversions: λ = c/ν = 1/k c = λν = ν/k k = ν/c = 1/λ ν = c/λ = ck c = speed of light = 2 .99792458 × 108 m/s Approximate photon Frequency (ν) Wavelength (λ) Wave number (k) Names of bands energies 3 × 100 – 3 × 101 Hz 108 – 107 m 10-8 – 10-7 m-1 ELF-(ELF 1), ITU band no . 1 3 – 30 Hz 100 – 10 Mm 10 – 100 Gm-1 3 × 101 – 3 × 102 Hz 107 – 106 m 10-7 – 10-6 m-1 SLF-(ELF 2), ITU band no . 2, megameter 30 – 300 Hz 10 – 1 Mm 100 Gm-1 – 1Mm-1 waves 3 × 102 – 3 × 103 Hz 106 – 105 m 10-6 – 10-5 m-1 ULF-(ELF 3), ITU band no . 3 300 Hz – 3 kHz 1 Mm – 100 km 1 – 10 Mm-1 3 × 103 – 3 × 104 Hz 105 – 104 m 10-5 – 10-4 m-1 VLF, ITU band no . 4, myriameter waves 3 – 30 kHz 100 – 10 km 10 – 100 Mm-1 3 × 104 – 3 × 105 Hz 104 – 103 m 10-4 – 10-3 m-1 LF, ITU band no . 5, kilometer waves 30 – 300 kHz 10 – 1 km 100 Mm-1 – 1 km-1 3 × 105 – 3 × 106 Hz 103 –102 m 10-3 – 10-2 m-1 MF, ITU band no . 6, hectometer waves 300 kHz – 3 MHz 1 km – 100 m 1 – 10 km-1 3 × 106 – 3 × 107 Hz 102 – 101 m 10-2 – 10-1 m-1 HF, ITU band no . -

Section 2 Basic Physics of Radiofrequency

Section 2 Basic Physics of Radiofrequency Table of Contents 2.1 Symbols and Units ........................................................................................................................ 8 2.2 Useful Definitions ......................................................................................................................... 8 2.2.1 Electromagnetic (EM) radiation ....................................................................... 8 2.2.2 RF antenna ..................................................................................................... 8 2.2.3 Radiofrequency .............................................................................................. 8 2.2.4 Wavelength of RF waves ................................................................................. 9 2.2.5 Frequency of RF waves ................................................................................... 9 2.2.6 Bandwidth of an RF antenna ........................................................................... 9 2.2.7 Power density .............................................................................................. 10 2.2.8 Decibel (dB) ................................................................................................. 10 2.2.9 Antenna gain/loss in dBi .............................................................................. 10 2.2.10 Equivalent isotropically radiated power (EIRP) ............................................. 10 2.2.11 Continuous RF wave (CW) ..........................................................................