Second Nature: Hamilton College and the Natural Environment Peter Simons Hamilton College, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Governors of Connecticut, 1905

ThegovernorsofConnecticut Norton CalvinFrederick I'his e dition is limited to one thousand copies of which this is No tbe A uthor Affectionately Dedicates Cbis Book Co George merriman of Bristol, Connecticut "tbe Cruest, noblest ana Best friend T €oer fia<T Copyrighted, 1 905, by Frederick Calvin Norton Printed by Dorman Lithographing Company at New Haven Governors Connecticut Biographies o f the Chief Executives of the Commonwealth that gave to the World the First Written Constitution known to History By F REDERICK CALVIN NORTON Illustrated w ith reproductions from oil paintings at the State Capitol and facsimile sig natures from official documents MDCCCCV Patron's E dition published by THE CONNECTICUT MAGAZINE Company at Hartford, Connecticut. ByV I a y of Introduction WHILE I w as living in the home of that sturdy Puritan governor, William Leete, — my native town of Guil ford, — the idea suggested itself to me that inasmuch as a collection of the biographies of the chief executives of Connecticut had never been made, the work would afford an interesting and agreeable undertaking. This was in the year 1895. 1 began the task, but before it had far progressed it offered what seemed to me insurmountable obstacles, so that for a time the collection of data concerning the early rulers of the state was entirely abandoned. A few years later the work was again resumed and carried to completion. The manuscript was requested by a magazine editor for publication and appeared serially in " The Connecticut Magazine." To R ev. Samuel Hart, D.D., president of the Connecticut Historical Society, I express my gratitude for his assistance in deciding some matters which were subject to controversy. -

Bushnell Family Genealogy, 1945

BUSHNELL FAMILY GENEALOGY Ancestry and Posterity of FRANCIS BUSHNELL (1580 - 1646) of Horsham, England And Guilford, Connecticut Including Genealogical Notes of other Bushnell Families, whose connections with this branch of the family tree have not been determined. Compiled and written by George Eleazer Bushnell Nashville, Tennessee 1945 Bushnell Genealogy 1 The sudden and untimely death of the family historian, George Eleazer Bushnell, of Nashville, Tennessee, who devoted so many years to the completion of this work, necessitated a complete change in its publication plans and we were required to start anew without familiarity with his painstaking work and vast acquaintance amongst the members of the family. His manuscript, while well arranged, was not yet ready for printing. It has therefore been copied, recopied and edited, However, despite every effort, prepublication funds have not been secured to produce the kind of a book we desire and which Mr. Bushnell's painstaking work deserves. His material is too valuable to be lost in some library's manuscript collection. It is a faithful record of the Bushnell family, more complete than anyone could have anticipated. Time is running out and we have reluctantly decided to make the best use of available funds by producing the "book" by a process of photographic reproduction of the typewritten pages of the revised and edited manuscript. The only deviation from the original consists in slight rearrangement, minor corrections, additional indexing and numbering. We are proud to thus assist in the compiler's labor of love. We are most grateful to those prepublication subscribers listed below, whose faith and patience helped make George Eleazer Bushnell's book thus available to the Bushnell Family. -

157Th Meeting of the National Park System Advisory Board November 4-5, 2015

NORTHEAST REGION Boston National Historical Park 157th Meeting Citizen advisors chartered by Congress to help the National Park Service care for special places saved by the American people so that all may experience our heritage. November 4-5, 2015 • Boston National Historical Park • Boston, Massachusetts Meeting of November 4-5, 2015 FEDERAL REGISTER MEETING NOTICE AGENDA MINUTES Meeting of May 6-7, 2015 REPORT OF THE SCIENCE COMMITTEE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE URBAN AGENDA REPORT ON THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE COMPREHENSIVE ECONOMIC VALUATION STUDY OVERVIEW OF NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ACTIONS ON ADVISORY BOARD RECOMMENDATIONS • Planning for a Future National Park System • Strengthening NPS Science and Resource Stewardship • Recommending National Natural Landmarks • Recommending National Historic Landmarks • Asian American Pacific Islander, Latino and LGBT Heritage Initiatives • Expanding Collaboration in Education • Encouraging New Philanthropic Partnerships • Developing Leadership and Nurturing Innovation • Supporting the National Park Service Centennial Campaign REPORT OF THE NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS COMMITTEE PLANNING A BOARD SUMMARY REPORT MEETING SITE—Boston National Historical Park, Commandant’s House, Charlestown Navy Yard, Boston, MA 02139 617-242-5611 LODGING SITE—Hyatt Regency Cambridge, 575 Memorial Drive, Cambridge, MA 62139 617-492-1234 / Fax 617-491-6906 Travel to Boston, Massachusetts, on Tuesday, November 3, 2015 Hotel Check in 4:00 pm Check out 12:00 noon Hotel Restaurant: Zephyr on the Charles / Breakfast 6:30-11:00 am / Lunch 11:00 am - 5:00 pm / Dinner 5-11:00 pm Room Service: Breakfast 6:00 am - 11:00 am / Dinner 5:00 pm - 11:00 pm Wednesday NOVEMBER 4 NOTE—Meeting attire is business. The tour will involve some walking and climbing stairs. -

Hamilton College Catalogue 2015-16

HAMILTON COLLEGE CATALOGUE 2015-16 1 Hamilton College Calendar 2015-16 Aug. 18-26 Saturday – Wednesday New student orientation 25 Tuesday Residence halls open for upperclass students, 9 a.m. 27 Thursday Fall semester classes begin, 8 a.m. Sept. 4 Friday Last day to add a course, 2 p.m. 18 Friday Last day to exercise credit/no credit option, 3 p.m. Oct. 2-4 Friday – Sunday Fallcoming 14 Wednesday Fall Recess begins, 4 p.m. Academic warnings due Last day to declare leave of absence for spring semester 2016 19 Monday Classes resume, 8 a.m. 21 Wednesday Last day to drop a course without penalty, 3 p.m. 23-25 Friday – Saturday Family Weekend Nov. 2-20 Registration period for spring 2016 courses 20 Friday Thanksgiving recess begins, 4 p.m. 30 Monday Classes resume, 8 a.m. Dec. 11 Friday Fall semester classes end 12-14 Saturday – Monday Reading period 14-18 Monday – Friday Final examinations 19 Saturday Residence halls close, noon Jan. 15-18 Friday – Monday New student orientation 17 Sunday Residence halls open, 9 a.m. 18 Monday Martin Luther King, Jr. holiday 19 Tuesday Spring semester classes begin, 8 a.m. 27 Wednesday Last day to add a course, 2 p.m. Last day for seniors to declare a minor Feb. 5 Friday Last day to exercise credit/no credit option, 3 p.m. 8-12 Monday – Friday Sophomores declare concentration 26 Friday Last day to declare a leave of absence for fall semester 2016 Mar. 4 Friday Academic warnings due 11 Friday Spring recess begins, 4 p.m. -

Hamilton College Catalogue 2011-12

Hamilton College Catalogue 2011-12 Hamilton College Calendar 2011-2012 Aug. 20-24 Saturday-Wednesday New Student Orientation 23 Tuesday Residence halls open for upperclass students, 9 am 25 Thursday Fall semester classes begin, 8 am Sept. 2 Friday Last day to add a course, 2 pm 16 Friday Last Day to exercise credit/no credit option, 3 pm 23-25 Friday-Sunday Fallcoming/Family Weekend/Bicentennial Celebration Oct. 7 Friday Last day to declare leave of absence for Spring semester 2012 12 Wednesday Fall Recess Begins, 4 pm Academic warnings due 17 Monday Classes resume, 8 am 19 Wednesday Last day to drop a course without penalty, 3 pm Nov. 1-18 Registration period for Spring 2012 courses (tentative) 18 Friday Thanksgiving recess begins, 4 pm 28 Monday Classes resume, 8 am Dec. 9 Friday Fall semester classes end 10-12 Saturday-Monday Reading period 12-16 Monday-Friday Final examinations 17 Saturday Residence halls close, noon Jan. 12-14 Thursday-Saturday New Student Orientation 14 Saturday Residence halls open, 9 am 16 Monday Spring semester classes begin, 8 am 20 Friday Last day for Seniors to declare a minor 24 Tuesday Last day to add a course, 2 pm Feb. 3 Friday Last day to exercise credit/no credit option, 3 pm 6-10 Monday-Friday Sophomores declare concentration 24 Friday Last day to declare leave of absence for Fall semester 2012 Mar. 2 Friday Academic warnings due 9 Friday Spring recess begins, 4 pm; Last day to drop a course without penalty, 3 pm 26 Monday Classes resume, 8 am Apr. -

Marsh Family Manuscripts, 1795-1976

The Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary, Columbia University in the City of New York Union Theological Seminary Archives 1 Finding Aid for Marsh Family Manuscripts, 1795-1976 Ebenezer Grant Marsh Log. UTS1: Marsh Family Manuscripts, 1795-1976, box 1, folder 1, the Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary, Columbia University in the City of New York Finding Aid prepared by: Rebecca Nieto, May 2017 With financial support from the Henry Luce Foundation and the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation Summary Information Creator: John Marsh the Elder, 1742-1821; Ebenezer Grant Marsh, (1777-1803); John Marsh the Younger (1788-1868) Title: Marsh Family Manuscripts, 1795-1976 Inclusive dates: 1795-1976 Bulk dates: 1795-1807 Abstract: John the Elder was an ecclesiastical leader and alumnus of Harvard College (1761), his sons Ebenezer Grant Marsh (Yale, 1795) and John Marsh the Younger (Yale, 1804) were educated and served in Protestant communities in New England, Ebenezer as a Hebrew scholar and John Marsh the Younger as a preacher and active member of the Temperance movement. Materials consist of biographical, historical, and religious manuscripts written by all three individuals. Size: 1 box, 0.5 linear feet Storage: Onsite storage Repository: The Burke Library Union Theological Seminary 3041 Broadway New York, NY 10027 Email: [email protected] UTS1: Marsh Family Manuscripts, 1795-1976 2 Administrative Information Provenance: The exact provenance of this collection is unknown; however, John Marsh the Younger (1788-1868) was the father of John Tallmadge Marsh (UTS, 1848), which is possibly the context in which these materials were donated to Union. -

International Student Survival Guide

Hamilton College International Students Survival Guide Alexander Hamilton is one of the Founding Fathers of the College and was the first Secretary of the Treasury, who co-wrote the Federalist Papers. Hamilton died in a duel with Aaron Burr in 1804, and he is on the U.S. $10 bill. Hamilton the musical was inspired by his life. Table of Contents Subject Page 1. Important Campus Phone Numbers 3 2. General Information for First-year Students 4 3. General Information about Hamilton College 7 4. Sadove Student Center 9 5. Beinecke Village 10 6. Bristol Center 11 7. U.S. Currency 13 8. Tuition/Ebill Statements 14 9. Tuition/Ebill Payment Options 16 10. Academics at Hamilton 18 11. Student Life Services 22 12. Health Services 24 13. Counseling Services 25 14. Campus Safety 27 15. Emergency Planning and Procedures 29 16. Library and IT Services 30 17. Meal Plans 32 18. Dining Hours 33 19. Other Food Options 34 20. Meals & Housing during Recesses/Breaks 35 21. Transportation 36 22. Alcohol Policy in New York State 38 23. Smoking Policy in New York State 40 24. Conversion Charts 41 25. Adjusting to American Culture 43 26. General Characteristics of Americans 47 27. National Holidays 49 28. Popular American Food 52 29. Local Dining 53 30. Shopping in the Area 57 31. Services in the Area 58 32. Information on Clinton and the Surrounding Area 59 2 Important Campus Phone Numbers International Student Services (ISS) 315.859.4021 Allen Harrison, Assistant Dean for International Students and Accessibility Campus Safety Non-Emergency (24 hours): 315.859.4141 -

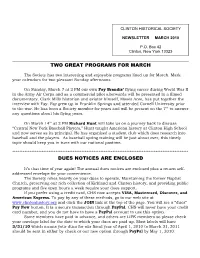

Two Great Programs for March Dues Notices Are

CLINTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER MARCH 2010 P.O. Box 42 Clinton, New York 13323 TWO GREAT PROGRAMS FOR MARCH The Society has two interesting and enjoyable programs lined up for March. Mark your calendars for two pleasant Sunday afternoons. On Sunday, March 7 at 2 PM our own Fay Brandis’ flying career during World War II in the Army Air Corps and as a commercial pilot afterwards will be presented in a filmed documentary. Clark Mills historian and aviator himself, Moses Acee, has put together the interview with Fay. Fay grew up in Franklin Springs and attended Cornell University prior to the war. He has been a Society member for years and will be present on the 7th to answer any questions about his flying years. On March 14th at 2 PM Richard Hunt will take us on a journey back to discuss “Central New York Baseball Players.” Hunt taught American history at Clinton High School and now serves as its principal. He has organized a student club which does research into baseball and the players. As baseball spring training will be just about over, this timely topic should keep you in tune with our national pastime. ****************************************************************************************************** DUES NOTICES ARE ENCLOSED It’s that time of year again! The annual dues notices are enclosed plus a return self- addressed envelope for your convenience. The Society relies heavily on your dues to operate. Maintaining the former Baptist Church, preserving our rich collection of Kirkland and Clinton history, and providing public programs and five open hours a week require your dues support. -

Hamilton College Catalogue 2004-05

2004 Catalog (with updates) 8/20/04 12:13 PM Page 1 Hamilton College Catalogue 2004-05 Hamilton College Calendar, 2004-05 2 History of the College 3 Academic Information College Purposes and Goals 5 Academic Programs and Services 7 Academic Regulations 16 Honors 29 Postgraduate Planning 31 Enrollment Admission 33 Tuition and Fees 37 Financial Aid 40 General Information Campus Buildings and Facilities 43 Student Life 48 Campus Cultural Life 52 Athletic Programs and Facilities 56 Courses of Instruction Course Descriptions and 58 Requirements for Concentrations and Minors Appendices Scholarships, Fellowships and Prizes 221 Federal and State Assistance Programs 251 The Trustees 255 The Faculty 257 Officers, Administration, Staff and Maintenance & Operations 275 Enrollment 284 Campus Crime Statistics 285 Degree Programs 286 Family Educational Rights 287 Index 289 August 2004 Clinton, New York 13323 Printed on recycled paper 2004 Catalog (with updates) 8/20/04 12:13 PM Page 2 Hamilton College Calendar, 2004-05 Aug. 24-28 Tuesday-Saturday New Student Orientation 2 8 S a t u rd ay Residence halls open for upperclass students, 9 am 3 0 Monday Fall semester classes begin, 8 am Sept. 3 Friday Last day to add a course or exercise credit/no credit option, 2 pm Oct. 1 Friday Fall recess begins, 4 pm 6 Wednesday Classes resume, 8 am 8 Friday Last day to declare leave of absence for Spring semester 2005 8-10 Friday-Sunday Fallcoming 15 Friday Academic warnings due 22 Friday Last day to drop a course without penalty, 2 pm 29-31 Friday-Sunday Family Weekend Nov. -

Hamilton College Catalogue 2005-06

Frontmatter 8/11/05 1:19 PM Page 1 Hamilton College Catalogue 2005-06 Hamilton College Calendar, 2005-06 2 History of the College 3 Academic Information College Purposes and Goals 5 Academic Programs and Services 7 Academic Regulations 15 Honors 29 Postgraduate Planning 31 Enrollment Admission 33 Tuition and Fees 37 Financial Aid 40 General Information Campus Buildings and Facilities 43 Student Life 48 Campus Cultural Life 52 Athletic Programs and Facilities 56 Courses of Instruction Course Descriptions and 58 Requirements for Concentrations and Minors Appendices Scholarships, Fellowships and Prizes 232 Federal and State Assistance Programs 262 The Trustees 266 The Faculty 268 Officers,Administration, Staff and Maintenance & Operations 286 Enrollment 295 Degree Programs 296 Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act Annual Notice 297 Index 299 August 2005 Clinton, New York 13323 Printed on recycled paper Frontmatter 8/11/05 1:19 PM Page 2 Hamilton College Calendar, 2005-06 Aug. 23-27 Tuesday-Saturday New Student Orientation 27 Saturday Residence halls open for upperclass students, 9 am Admission Office Open House 29 Monday Fall semester classes begin, 8 am Sept. 2 Friday Last day to add a course or exercise credit/ no credit option, 2 pm 30-Oct. 2 Friday-Sunday Fallcoming Oct. 7 Friday Last day to declare leave of absence for Spring semester 2006 14 Friday Fall recess begins, 4 pm Academic warnings due 19 Wednesday Classes resume, 8 am 21 Friday Last day to drop a course without penalty, 2 pm 21-23 Friday-Sunday Family Weekend Nov. 7-22 Monday-Tuesday Registration period for Spring 2006 courses (tentative) 12 Saturday Admission Office Open House 22 Tuesday Thanksgiving recess begins, 4 pm 28 Monday Classes resume, 8 am Dec. -

Descendants of Dr. Laurens Hull and Dorcas Ambler - of Angelica, Alleghany Co., NY

Descendants of Dr. Laurens Hull and Dorcas Ambler - of Angelica, Alleghany Co., NY by A. H. Gilbertson 7 Mar 2019 version 0.53b ©A. H. Gilbertson 2103-2019. Table of Contents Preface ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Laurens Hull and Dorcas Ambler ................................................................................................... 4 Second Generation ........................................................................................................................ 7 Third Generation ......................................................................................................................... 14 Fourth Generation ....................................................................................................................... 31 Fifth Generation .......................................................................................................................... 50 Obituary of Dr. Laurens Hull ........................................................................................................ 74 2 Preface I have been doing genealogy as a hobby for over 30 years, and fairly recently have started to share some of my research in the form of books, in PDF format. Most of these books are “ahnentafel books,” which are ancestor tables, with information on ancestors of six of my eight great-grandparents. In addition, I have been working on some projects involving descendants. This format is perhaps -

National Register of Historic Places

National Register of Historic Places Resource Name County Fort Schuyler Club Building Oneida Unadilla Water Works Otsego Smith-Taylor Cabin Suffolk Comstock Hall Tompkins Hough, Franklin B., House Lewis Teviotdale Columbia Brookside Saratoga Lane Cottage Essex Rock Hall Nassau Kingsland Homestead Queens Hancock House Essex Page 1 of 1299 09/26/2021 National Register of Historic Places National Register Date National Register Number Longitude 05/12/2004 03NR05176 -75.23496531 09/04/1992 92NR00343 -75.31922416 09/28/2007 06NR05605 -72.2989632 09/24/1984 90NR02259 -76.47902689 10/15/1966 90NR01194 -75.50064587 10/10/1979 90NR00239 -73.84079851 05/21/1975 90NR02608 -73.85520126 11/06/1992 90NR02930 -74.12239039 11/21/1976 90NR01714 -73.73419318 05/31/1972 90NR01578 -73.82402146 11/15/1988 90NR00485 -73.43458994 Page 2 of 1299 09/26/2021 National Register of Historic Places NYS Municipal New York Zip Latitude Georeference Counties Boundaries Codes 43.10000495 POINT (- 984 1465 625 75.23496531 43.10000495) 42.33690739 POINT (- 897 465 2136 75.31922416 42.33690739) 41.06949826 POINT (- 1016 1647 2179 72.2989632 41.06949826) 42.4492702 POINT (- 709 1787 2181 76.47902689 42.4492702) 43.78834776 POINT (- 619 571 623 75.50064587 43.78834776) 42.15273568 POINT (- 513 970 619 73.84079851 42.15273568) 43.00210318 POINT (- 999 1148 2141 73.85520126 43.00210318) 44.32997931 POINT (- 430 303 2084 74.12239039 44.32997931) 40.60924086 POINT (- 62 1563 2094 73.73419318 40.60924086) 40.76373114 POINT (- 196 824 2137 73.82402146 40.76373114) 43.84878656 POINT (- 420 154 2084 73.43458994 Page 3 of 1299 09/26/2021 National Register of Historic Places Eighth Avenue (14th Regiment) Armory Kings Downtown Gloversville Historic District Fulton Rest Haven Orange Devinne Press Building New York Woodlawn Avenue Row Erie The Wayne and Waldorf Apartments Erie Bateman Hotel Lewis Firemen's Hall Queens Adriance Memorial Library Dutchess Shoecroft, Matthew, House Oswego The Dr.