Open Access and the Humanities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Achbeag, Cullicudden, Balblair, Dingwall IV7

Achbeag, Cullicudden, Balblair, Dingwall Achbeag, Outside The property is approached over a tarmacadam Cullicudden, Balblair, driveway providing parking for multiple vehicles Dingwall IV7 8LL and giving access to the integral double garage. Surrounding the property, the garden is laid A detached, flexible family home in a mainly to level lawn bordered by mature shrubs popular Black Isle village with fabulous and trees and features a garden pond, with a wide range of specimen planting, a wraparound views over Cromarty Firth and Ben gravelled terrace, patio area and raised decked Wyvis terrace, all ideal for entertaining and al fresco dining, the whole enjoying far-reaching views Culbokie 5 miles, A9 5 miles, Dingwall 10.5 miles, over surrounding countryside. Inverness 17 miles, Inverness Airport 24 miles Location Storm porch | Reception hall | Drawing room Cullicudden is situated on the Black Isle at Sitting/dining room | Office | Kitchen/breakfast the edge of the Cromarty Firth and offers room with utility area | Cloakroom | Principal spectacular views across the firth with its bedroom with en suite shower room | Additional numerous sightings of seals and dolphins to bedroom with en suite bathroom | 3 Further Ben Wyvis which dominates the skyline. The bedrooms | Family shower room | Viewing nearby village of Culbokie has a bar, restaurant, terrace | Double garage | EPC Rating E post office and grocery store. The Black Isle has a number of well regarded restaurants providing local produce. Market shopping can The property be found in Dingwall while more extensive Achbeag provides over 2,200 sq. ft. of light- shopping and leisure facilities can be found in filled flexible accommodation arranged over the Highland Capital of Inverness, including two floors. -

Introductory Lecture & FLOSS

Introductory Lecture & FLOSS Lecture 1 TU Wien, 193.067 Free and Open Technologies (WS 2019/2020) Christoph Derndorfer and Lukas F. Lang This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Introduction Organization ● Lectures: ○ Weekly lecture to cover course materials (until Christmas) ○ Lectures take place on Tuesdays, 17:00–19:00, Argentinierstraße 8, Seminarraum/Bibliothek 194-05 ○ Attendance is mandatory ● Group project: ○ In groups of 4 students ○ 3 meetings with lecturers during the semester (week 44/2019, week 48/2019, week 2/2020) ○ Final presentations at the end of January (week 4/2020) ● Final paper: ○ In groups of 2 students ○ Final presentations at the end of January (week 5/2020) ○ Deadline: Sunday, February 9, 2020, 23:59 CET (no exceptions!) Organization ● Grading: ○ 50% group project ○ 35% seminar paper ○ 15% participation during lectures ○ All course components need to be passed in order to pass the overall course! ● Course materials: ○ Will be provided at https://free-and-open-technologies.github.io ● For further questions: ○ Email [email protected] and [email protected] Lecture outline 1. FLOSS (Free/Libre and Open Source Software) 2. Open Hardware 3. Open Data 4. Open Content/Open Educational Resources 5. Open Science/Research 6. Open Access 7. Open Spaces/Open Practices: Metalab Vienna 8. Guest Lecture: Stefanie Wuschitz (Mz* Baltazar’s Lab) Group project ● Goal: ○ Extend, contribute to, or create a new open project within scope of lecture topics ● Choose topic from a list (see course website) or (even better) suggest your own: ○ Groups of 4 students ○ Send a 1-page proposal until Friday, October 25, via email to both lecturers ■ Define the idea, goal, (potential) impact, requirements, and estimated effort ■ State deliverables (should be broken down into three milestones to discuss in meetings) ● Requirements: ○ Open and accessible (Git repository, openly licensed) → others can access/use/study/extend ○ Use time sheet to track and compare estimated vs. -

20Th Anniversary Issue!

Special 20th Anniversary Issue! TEXAS WINTER / SPRING 2016 SINCE 1996 YEARS Top 20 Amicable Celebrity Divorces Should You End Your Marriage? How to Choose a Divorce Lawyer The World’s First Divorce School Tips for Successful Co-Parenting Fight Depression and Thrive Table of Contents | .com Directorywww.DivorceMagazine.com | 1 Introducing @ No one goes to school for divorce, Free. Practical. Transformative. but every divorcing person should. Get ready for two months of free education and Introducing the world’s first Divorce School – a inspiration! In April, May, and June, you’ll have unlim- unique online learning center where divorce profes- ited access to all Divorce School podcasts and videos sionals and divorced people will share their exper- anytime you want, day or night. Our mission is to tise and experience through videos and podcasts. empower you to make better choices before, during, and after divorce; we’ll teach you how to use your Get answers to these questions – and many more: divorce as a catalyst for life-changing transformation. • How do I choose a divorce lawyer? • Will I get half of everything? Join now for free! • Should I keep or sell the family home? If divorce is on your doorstep – or if you’re still dealing • How are child and spousal support calculated? with issues during or after divorce – you can’t afford • Is sole or joint custody best for my children? to miss this online Divorce School! Join now at www. • How can I heal from divorce? TheDivorceSchool.com/divorce-school-participant The Divorce School is a brand-new initiative in celebration of Divorce Magazine’s and www.DivorceMagazine.com’s 20th anniversary. -

DINGWALL, Dingwall & Highland Marts

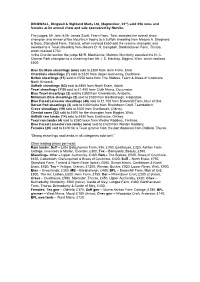

DINGWALL, Dingwall & Highland Marts Ltd, (September, 23rd) sold 358 rams and females at its annual show and sale sponsored by Norvite. The judges, Mr John & Mr James Scott, Fearn Farm, Tain, awarded the overall show champion and winner of the Mountrich trophy to a Suffolk shearling from Messrs A. Shepherd & Sons, Stonyford Farm, Tarland, which realised £650 and the reserve champion was awarded to a Texel shearling from Messrs D. N. Campbell, Bardnaclaven Farm, Thurso, which realised £700. In the Cheviot section the judge Mr R. MacKenzie, Muirton, Munlochy awarded the N. C. Cheviot Park champion to a shearling from Mr J. S. MacKay, Biggins, Wick, which realised £600. Blue Du Main shearlings (one) sold to £500 from Hern Farm, Errol. Charollais shearlings (7) sold to £320 from Upper Auchenlay, Dunblane. Beltex shearlings (15) sold to £550 twice from The Stables, Fearn & Braes of Coulmore, North Kessock. Suffolk shearlings (63) sold to £850 from North Essie, Adziel. Texel shearlings (119) sold to £1,450 from Clyth Mains, Occumster. Blue Texel shearlings (2) sold to £380 from Greenlands, Arabella. Millenium Blue shearlings (2) sold to £500 from Bardnaheigh, Harpsdale. Blue Faced Leicester shearlings (46) sold to £1,100 from Broomhill Farm, Muir of Ord. Dorset Poll shearlings (4) sold to £300 twice from Rheindown Croft, Teandalloch. Cross shearlings (19) sold to £600 from Overhouse, Orkney. Cheviot rams (32) sold to £600 for the champion from Biggins, Wick. Suffolk ram lambs (14) sold to £420 from Easthouse, Orkney. Texel ram lambs (4) sold to £380 twice from Wester Raddery, Fortrose. Blue Faced Leicester ram lambs (one) sold to £420 from Wester Raddery. -

23. October. 2012 Open Source

_ 23. October. 2012 Open Source CONTRIBUTORS Distributed in Publisher Editor Design Managing Editor Daragh McDowell Eric Doyle The Surgery Peter Archer MARK BALLARD ADRIAN BRIDGWATER BILLY MacINNES Freelance journalist, who covers computer Specialist author on software engineering Editor and writer, he has written about the policy, business and systems, he writes and application development, he is a technology industry across a wide variety of Although this publication is funded through advertising and sponsorship, all editorial is without bias and Computer Weekly's public sector IT blog. regular contributor to Dr. Dobb’s Journal publications for more than a generation. sponsored features are clearly labelled. For an upcoming schedule, partnership inquiries or feedback, please call and Computer Weekly. +44 (0)20 3428 5230 or email [email protected] Raconteur Media is a leading European publisher of special interest content and research. It covers a wide range of topics, RICHARD HILLESLEY ROD NEWING including business, finance, sustainability, lifestyle and the arts. Its special reports are exclusively published within The Freelance writer on Linux, free software Freelance business and technology writer, Times, The Sunday Times and The Week. www.raconteurmedia.co.uk The information contained in this publication has been obtained from sources the Proprietors believe to be correct. and digital rights, he is a former editor of he contributes regularly to the Financial However, no legal liability can be accepted for any errors. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the prior LinuxUser and now contributes to Tux Times, The Times, The Daily Telegraph and consent of the Publisher. -

(November 16Th) Sold 26 Goats, 4 Alpaca, 799 Sheep and 457 Lots of Poultry, Eggs & Poultry Equipment at Their, Rare & Traditional Breeds of Livestock Sale

DINGWALL, Dingwall & Highland Marts (November 16th) sold 26 goats, 4 alpaca, 799 sheep and 457 lots of poultry, eggs & poultry equipment at their, rare & traditional breeds of livestock sale. Goats (26) sold to £380 for pygmy female with a kidd at foot from Allt A’Bhonich, Stromeferry. Alpaca (4) sold to £550 gross for a pair of males from Meikle Geddes, Nairn. Sheep (799) sold to £1,600 gross for a Valais Blacknose ram from 9 Drumfearn, Isleornsay. Poultry (457) sold to £170 gross for a trio of Mandarin from old Schoolhouse, Balvraid. Sheep other leading prices: Zwartble gimmer: 128 Kinlochbervie, Kinlochbervie, £110. Zwartble in lamb gimmers: Carn Raineach, Applecross, £180. Zwartble ewe: 1 Georgetown Farm, Ballindalloch, £95. Zwartble in lamb ewe: Old School, North Strome, £95 Zwartble ewe lambs: Speylea, Fochabers, £85. Zwartble tup lamb: Old School, £55. Zwartble rams: Wester Raddery, £320. Sheep: Lambs: Valais Blacknose – Scroggie Farm, Dingwall, £500; Dorset – An Cala, Canisby, £200; Ryeland – Stronavaich, Tomintoul, £150; Blue Faced Leicester – Beldhu, Croy, £130; Herdwick – Broombank, Culloden, £110; Border Leicester – Balmenach Farm, Ballater, £105; Kerryhill – Invercharron Mains, Ardgay, £100 (twice); Jacob – Lochnell Home Farm, Benderloch, £100; Cheviot – Cuilaneilan, Kinlochewe & Bogburn Farm, Duncanston, £90; Texel – Inverbay, Lower Arboll, £90 (twice); Llanwenog – Burnfield Farm, Rothiemay, £80; Clune Forest – 232 Proncycroy, Dornoch, £74; Blackface – Bogburn Farm, £60; Gotland – Myre Farm, Dallas, £60; Hebridean – Broomhill Farm, Muir of Ord, £55; Shetland – Upper Third Croft, Rothienorman, £50.Gimmers: Beltex – Knockinnon, Dunbeath, £300; Cheviot – Cuilaneilan, £220; Herdwick – Duror, Glenelg, £170; Dorset – Knockinnon, £155; Ryeland – 5 Terryside, Lairg, £120; Jacob – Killin Farm, Garve, £85; Hebridean – Eagle Brae, Struy, £65; Shetland – Lamington, Oyne, £50; Texel – Sandside Cottage, Tomatin, £50. -

Free and Open Source Software: “Commons” Or Clubs

To be published in the book “Conference for the 30th Anniversary of the CRID” (Collection du CRIDS) Free and Open Source Software Licensing: A reference for the reconstruction of “virtual commons”?1 Philippe LAURENT Senior Researcher at the CRIDS (University of Namur - Belgium) Lawyer at the Brussels Bar (Marx, Van Ranst, Vermeersch & Partners) The impact of the Free, Libre and Open Source Software (FLOSS) movement has been compared to a revolution in the computing world2. Beyond the philosophical and the sociological aspects of the movement, its most outstanding achievement is probably its penetration in the ICT market3. FLOSS has indeed reached a high level of economical maturity. It is not “just” an alternative movement any more, nor is it a simple option that companies of the field can choose to take or simply ignore. It is a reality that everyone has to acknowledge, understand and deal with, no matter which commercial strategy or business model is implemented. FLOSS is based upon an outstanding permissive licensing system coupled with an unrestricted access to the source code, which enables the licensee to modify and re-distribute the software at will. In such context, intellectual property is used in a versatile way, not to monopolize technology and reap royalties, but to foster creation on an open and collaborative basis. This very particular use of initially “privative” rights firstly amazed… then became source of inspiration. Indeed, scientists, academics and other thinkers noticed that the free and open source system actually worked quite well and gave birth to collaborative and innovative, but also commercially viable ecosystems. -

Elements of Free and Open Source Licenses: Features That Define Strategy

Elements Of Free And Open Source Licenses: Features That Define Strategy CAN: Use/reproduce: Ability to use, copy / reproduce the work freely in unlimited quantities Distribute: Ability to distribute the work to third parties freely, in unlimited quantities Modify/merge: Ability to modify / combine the work with others and create derivatives Sublicense: Ability to license the work, including possible modifications (without changing the license if it is copyleft or share alike) Commercial use: Ability to make use of the work for commercial purpose or to license it for a fee Use patents: Rights to practice patent claims of the software owner and of the contributors to the code, in so far these rights are necessary to make full use of the software Place warranty: Ability to place additional warranty, services or rights on the software licensed (without holding the software owner and other contributors liable for it) MUST: Incl. Copyright: Describes whether the original copyright and attribution marks must be retained Royalty free: In case a fee (i.e. contribution, lump sum) is requested from recipients, it cannot be royalties (depending on the use) State changes: Source code modifications (author, why, beginning, end) must be documented Disclose source: The source code must be publicly available Copyleft/Share alike: In case of (re-) distribution of the work or its derivatives, the same license must be used/granted: no re-licensing. Lesser copyleft: While the work itself is copyleft, derivatives produced by the normal use of the work are not and could be covered by any other license SaaS/network: Distribution includes providing access to the work (to its functionalities) through a network, online, from the cloud, as a service Include license: Include the full text of the license in the modified software. -

Mediakit About Outtv Your Lifestyle with an ‘Attitude’

Mediakit About OUTtv Your lifestyle with an ‘attitude’ OUTtv is the lifestyle television channel for the gay and OUTtv distinguishes itself with ‘lifestyle with an openminded for more than eleven years with internation- attitude’ and that works! Via our cross-medial channels, ally successful tv-programs, exciting LGBTQI series, raw OUTtv brings a mix of (international) succesfull TV-shows, reality, impressive documentaries, hysterical telenovellas, (arthouse) films, TV-series, news, reality shows and award gay romcoms, award winning films and OUT originals. To winning documentaries. From drama to comedy and from be received via a variety of European cable operators, tel- entertainment to the latest news: OUTtv always goes ecomproviders and via OUTtv Pro, the new LGBTQI on-de- beyond. A choice for OUTtv is a choice for a trendsetting mand service. audience who have an out-of-the- box mindset. OUTtv has a monthly potential reach of: 8.000.000+ In countries outside Europe where OUTtv is not yet a well households established brand, OUTtv will use the PRIDEtv brand to - 2.000.000+ actual viewers per month make it more recognizable. - 66.000 newsletter subscribers - 55.000 socialmedia followers With its subsidiaries Pro-Fun Media and Cinemien, - 33.000 OUTtv event visitors OUTtv covers the entire lifecycle of film and video exploitation; the promotion and launch of films, documen- OUTtv TV-networks, services and/or products can be found in: taries, arthouse releases and TV series both in cinema and · The Netherlands · Switzerland · Belgium · Austria on DVD/Blu Ray, as well as digital exploitation via OUT- · Sweden · Finland tv’s channels and external platforms like Itunes, Amazon · Germany And soon in: Prime and Google Play. -

Maccoinnich, A. (2008) Where and How Was Gaelic Written in Late Medieval and Early Modern Scotland? Orthographic Practices and Cultural Identities

MacCoinnich, A. (2008) Where and how was Gaelic written in late medieval and early modern Scotland? Orthographic practices and cultural identities. Scottish Gaelic Studies, XXIV . pp. 309-356. ISSN 0080-8024 http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/4940/ Deposited on: 13 February 2009 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk WHERE AND HOW WAS GAELIC WRITTEN IN LATE MEDIEVAL AND EARLY MODERN SCOTLAND? ORTHOGRAPHIC PRACTICES AND CULTURAL IDENTITIES This article owes its origins less to the paper by Kathleen Hughes (1980) suggested by this title, than to the interpretation put forward by Professor Derick Thomson (1968: 68; 1994: 100) that the Scots- based orthography used by the scribe of the Book of the Dean of Lismore (c.1514–42) to write his Gaelic was anomalous or an aberration − a view challenged by Professor Donald Meek in his articles ‘Gàidhlig is Gaylick anns na Meadhon Aoisean’ and ‘The Scoto-Gaelic scribes of late medieval Perth-shire’ (Meek 1989a; 1989b). The orthography and script used in the Book of the Dean has been described as ‘Middle Scots’ and ‘secretary’ hand, in sharp contrast to traditional Classical Gaelic spelling and corra-litir (Meek 1989b: 390). Scholarly debate surrounding the nature and extent of traditional Gaelic scribal activity and literacy in Scotland in the late medieval and early modern period (roughly 1400–1700) has flourished in the interim. It is hoped that this article will provide further impetus to the discussion of the nature of the literacy and literary culture of Gaelic Scots by drawing on the work of these scholars, adding to the debate concerning the nature, extent and status of the literacy and literary activity of Gaelic Scots in Scotland during the period c.1400–1700, by considering the patterns of where people were writing Gaelic in Scotland, with an eye to the usage of Scots orthography to write such Gaelic. -

Sunjournals? Journal Marketing and Advertising; Any Open Access E-Journal Published by the University Editorial Management (E.G

Which journals are hosted on SUNJournals? Journal marketing and advertising; Any open access e-journal published by the University Editorial management (e.g. identifying reviewers, cor- of Stellenbosch, or affiliated with the University of responding with authors); Stellenbosch. Peer reviewing; Article production (e.g. copyediting, layout, proof- If you are developing a new open access e-journal, the reading); library would love to partner with you to provide e- Journal issue production; journal hosting and related services. If you are inter- Subscription management (if journal offers subscrip- SUNJournals ested in moving an existing journal to online open tions in addition to open access); access, we will provide the hosting service and also Accounts payable or receivable (including billing au- assist in the transfer of existing content thors if journal charges author fee). What are the costs involved? Journals need to have an expected long-term affiliation with Hosting the journal on our server is currently free of the University, and must be available as “libre” open access. charge. We recommend that all articles be made available under a Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND or more permissive) What is the responsibility of the library? license. See http://za.creativecommons.org/. Providing hosting at http://journals.sun.ac.za ; Training for editors in the use of the OJS system, including ongoing technical support; Getting started Assistance in the setup of the journal including advice on editorial workflow, user manage- ment, copyright issues, and inclusion of rich Interested in having your e-journal hosted by the Stel- media as part of an e-journal article; lenbosch University Library and Information Service? Acquisition of an EISSN for the journal; Please contact [email protected] to discuss the Assist in registering with the Directory of possibilities. -

List of Search Engines

A blog network is a group of blogs that are connected to each other in a network. A blog network can either be a group of loosely connected blogs, or a group of blogs that are owned by the same company. The purpose of such a network is usually to promote the other blogs in the same network and therefore increase the advertising revenue generated from online advertising on the blogs.[1] List of search engines From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For knowing popular web search engines see, see Most popular Internet search engines. This is a list of search engines, including web search engines, selection-based search engines, metasearch engines, desktop search tools, and web portals and vertical market websites that have a search facility for online databases. Contents 1 By content/topic o 1.1 General o 1.2 P2P search engines o 1.3 Metasearch engines o 1.4 Geographically limited scope o 1.5 Semantic o 1.6 Accountancy o 1.7 Business o 1.8 Computers o 1.9 Enterprise o 1.10 Fashion o 1.11 Food/Recipes o 1.12 Genealogy o 1.13 Mobile/Handheld o 1.14 Job o 1.15 Legal o 1.16 Medical o 1.17 News o 1.18 People o 1.19 Real estate / property o 1.20 Television o 1.21 Video Games 2 By information type o 2.1 Forum o 2.2 Blog o 2.3 Multimedia o 2.4 Source code o 2.5 BitTorrent o 2.6 Email o 2.7 Maps o 2.8 Price o 2.9 Question and answer .