The Wrongful Imprisonment of the Guildford Four: Who Bears the Blame?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4Th Quarter 2016 and Was Highly Motivated to Seek Answers

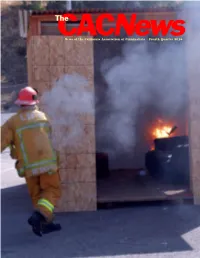

News of the California Association of Criminalists • Fourth Quarter 2016 Making Things Happen When I was a kid, I had a poster of three baby raccoons in my room with the following quote. It is a quote that I always liked and still try to live by today. “There are people who make things happen, there are people who watch things happen, and there are people who wonder what happened.” It’s a cliché saying, but it’s also very applicable to those of us who work in forensic science. I’ve been CAC President for a few months now, so I looked back at my last address to evaluate whether I am “making things happen,” or in other words, whether I am achieving the goals I set forth at the beginning of my term. One of the goals I set forth was increasing CAC membership. Living in California is expensive, and sometimes criminalists have so many living expenses that they struggle to pay annual dues for a number of professional memberships. I found that this keeps criminalists from becoming CAC members. Therefore, I convinced my Laboratory Director to pay for an additional professional mem- bership fee for each of our criminalists. This has encouraged many more of my colleagues to join the CAC. Thank you, Ian Fitch! Now I will work to get more of these new members to attend study group meetings and seminars. Maybe I can even get one or two of them to present some of their fine work. Are any other laboratories able to dig a little deeper to find some funding to financially assist their criminalists in participating in professional activities? Another goal was to get more people to serve so that our association as a whole can “make things happen.” I have asked a lot of people to step up and serve and have only been met with enthusiasm. -

Leninist Perspective on Triumphant Irish National-Liberation Struggle

Only he is a Marxist who extends the rec- Subscriptions (£30 p.a. or £15 six months - pay og Bulletin Publications) and circulation: £2 nition of the class struggle to the recogni- Economic & tion of the dictatorship of the proletariat. p&p epsr, po box 76261, This is the touchstone on which the real Philosophic London sw17 1GW [Post Office Registered.] Books understanding and recognition of Marxism e-Mail: [email protected] is to be tested. V.I.Lenin Science Review Website — WWW.epsr.orG.uk Vol 15 driver (representing Britain’s Leninist perspective on triumphant police-military dictatorship), and that the IRA itself intended to hold an inquiry to reprimand Irish national-liberation struggle those responsible for such an ill-judged attack, plus well- Part Two (June 1988 - January 1994) recorded apologies (for the casu- alties to innocent by-standers) expressed by Sinn Féin and the IRA. EPSR books Volume 15 [Part One in Vol 8 1979-88] Channel Four’s News at Seven even added a postscript to its far further afield, particularly hour-long nightly bulletin that More clues from the dog not barking in the Republic and in the huge its coverage of the Fermanagh [ILWP Bulletin No 450 29-06-88] North American Irish-descent border incident should have population). made it clearer that the target Pieces continue to fit together again showed up the limits of Some key sections of the Brit- of the IRA attack was the UDR revealing British imperialism’s philosophical, political and ish capitalist state media delib- bus driver, and not the children plans to finally quit its colonial cultural emancipation of the erately held back from this prize inside the bus. -

Marylebone Association Newsletter December 2019

The Marylebone Association Newsletter December 2019 Dear {Contact_First_Name} Association News Our Christmas Wishlist for the Neighbourhood 1. Invest in The Seymour Centre for both Sports and Library users 2. Making Shisha Smoking a "Licensable activity" 3. Regulate Pedicabs 4. Regulate busking across Westminster 5. Fix the short-letting problem 6. Introduce a multi-use games area into Paddington Gardens 7. A break from constant highway projects just undertake maintenance work 8. Remove the threat of living under Heathrow flight path 9. Increase the local police presence rather than needing private security patrols to take on their work 10. Prevent the spread of the night time economy into residential areas 11. Ban non-electric public transport from Marylebone 12. A peaceful Christmas and prosperous New Year What is on your wish-list for Marylebone - please let us know? [email protected] Interfaith Service 2019 This years Interfaith Service was held at the Parish Church of St Marylebone, jointly sponsored by the Marylebone Association, the Howard de Walden and the Portman Estates. The service was led by the Reverend Cannon Dr Stephen Evans and was attended by many different faith representatives who all contributed by way of readings and music. Also in attendance was the Lord Mayor of Westminster, Ruth Bush and representatives of major local organisations and other stakeholders. After the service attendees were invited to stay behind for refreshments. Our thanks go to the Howard de Walden Estate and the Portman Estate for their usual generous contributions towards this event. Marylebone News Lighting of Marylebone's Christmas Tree Marylebone is getting it own Christmas Tree this year outside St Mary's Church on Wyndham Place. -

Call for Inquest Into IRA Guildford Pub Bombings to Be Reopened’

Networked Knowledge Media Reports Networked Knowledge IRA Bombing Cases Homepage This page set up by Dr Robert N Moles [Underlining, where it occurs is for NetK editorial emphasis] On 2 November 2017 Owen Bowcott and Ian Cobain of The Guardian reported ‘Call for inquest into IRA Guildford pub bombings to be reopened’ Lawyers acting for sister of Gerry Conlon, who was wrongfully jailed for 15 years, call for completion of process for five who died. Lawyers representing two individuals affected by the IRA’s 1974 Guildford pub bombings have asked the Surrey coroner to reopen the inquest into the five victims who died, which has never been completed. The Belfast-based firm KRW Law has written to Richard Travers saying that the victims’ relatives and those who suffered miscarriages of justice have been denied their right to “truth, justice and accountability”. The move follows the firm’s success in reviving the inquest into the 1974 Birmingham pub bombings, although that process has now been delayed by arguments over the scope of the new investigation. In the Guildford case, KRW Law has been instructed by Ann McKearnan, the sister of Gerry Conlon, one of the so-called Guildford Four who were wrongfully imprisoned for 15 years for the attacks. It is also working with a former soldier who survived the explosion in the town’s Horse and Groom Pub which killed four soldiers and a civilian. A second bomb detonated at a nearby pub, the Seven Stars, injuring eight people. One of the survivors of the Horse and Groom bombing, an off-duty soldier, later recalled: “I had just leaned forward to get up to buy my round when there was a bang. -

Vitality Nov 20

Nov 2020 Vitality! Official newsletter of the Syston and District U3A CHARITY No 1180152 FROM OUR CHAIRMAN Last month we were planning a cautious return to group meetings. We were exploring ‘covid secure’ premises and designing user friendly risk assessment checklists, however, our elected leaders moved the goalposts again. Not to be deterred we decided to do a survey of our group organisers to see which groups were managing to keep running and were pleased to find that 10 of our groups are still functioning by secure meetings or electronic methods. In addition, some were keeping in touch with their group members by email or phone calls just to maintain contact. Again, I would like to extend my thanks and that of the committee to all our group organisers for hanging in there and trying to keep the groups together. We have now produced new Risk Assessment forms and a Guidance Document that can be found on our ‘Grp Organise’ page of the website for anyone who is thinking of starting their group, and of course our group coordinators will be willing to provide advice as necessary. Our AGM with a difference was held in October, that difference being, no one was there! Well at least we didn’t get any heckling. You will recall from the EGM held earlier this year that we changed the constitution resulting in some committee members coming to the end of their job tenure and I wish to extend my thanks to Gillie, our Refreshments Organizer, Jackie our Assistant Treasurer, and Pat, our Speaker Finder, for their work and dedication to the committee over the past 4 years. -

Abbey Theatre, 443, 544; Rioting At, 350 Abbot, Charles, Irish Chief Secretary, 240 Abercorn Restaurant, Belfast, Bomb In, 514 A

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-19720-5 - Ireland: A History Thomas Bartlett Index More information INDEX Abbey Theatre, 443, 544; rioting at, 350 247, 248; and Whiteboys, 179, 199, Abbot, Charles, Irish chief secretary, 240 201, 270 Abercorn restaurant, Belfast, bomb in, 514 Ahern, Bertie, Taoiseach, 551, 565;and Aberdeen, Ishbel, Lady, 8 Tony Blair, 574; investigated, 551;and abortion, in early Ireland, 7; in modern peace process talks (1998), 566 Ireland, banned, 428, 530–1; Aidan, Irish missionary, 26 referendum on, 530; see ‘X’case AIDS crisis see under contraception ActofAdventurers(1642), 129 Aiken, Frank, 419, 509; minister of defence, ActofExplanation(1665), 134 440; wartime censorship, 462 Act to prevent the further growth of popery aislingı´ poetry, 169 (1704), 163, 167, 183 Al Qaeda, attacks in United States, 573 Act of Satisfaction (1653), 129 Albert, cardinal archduke, 97 ActofSettlement(1652), 129 alcohol: attitudes towards in Ireland and ActofSettlement(1662), 133 Britain, nineteenth century, 310; Adams, Gerry, republican leader, 511, consumption of during ‘Celtic Tiger’, 559–60, 565; and the IRA, 522;and 549; and see whiskey power-sharing, 480–1; and strength of Alen, Archbishop John, death of, 76 his position, 569; and study of Irish Alen, John, clerk of council, 76 history, 569; and talks with John Hume, Alexandra College, Dublin, 355 559, 561; and David Trimble, 569;and Alfred, king, 26 visa to the United States, 562; wins Algeria, 401 parliamentary seat in West Belfast, Allen, William, Manchester Martyr, 302 526 -

Troubled Tales: Short Stories About the Irish in 1970S London Tony Murray

8 Troubled Tales: Short Stories about the Irish in 1970s London Tony Murray Some of the most violent ravages of ‘the Troubles’ occurred during the Provisional IRA’s bombing campaign of mainland Britain that began in March 1973 and continued intermittently, but often devastatingly, through to February 1996. London was the main focus of activity with government buildings, department stores and mainline railway stations becoming prime targets. For much of the 1970s and 80s, the Irish community in the city found itself under considerable pressure as dormant anti-Irish prejudices within sections of the host population were re-ignited in response to the outrages (Delaney, 2007: 125). Apart from damaging property and causing substantial disruption to Londoners, the bombings resulted in over thirty deaths and hundreds of injuries. The pressure on Irish people living in the city was particularly acute during the days and weeks after a bomb explosion when, whatever their political sympathies, the possession of an Irish accent became grounds in some quarters for verbal and even physical assault (Hickman and Walter, 1997: 205). By the 1970s, the generation of Irish migrants who came to Britain in the immediate post-war years had put down roots, were building careers, and were raising families. As a result, such pressures were all the more profound and many Irish men and women kept a low profile for fear of victimization. Political violence and its effects on Irish society has been a perennial theme in the country’s literature. The Troubles, in both their early and their late twentieth- century manifestations, provided writers with a dramatic backdrop against which to depict and interrogate issues of Irish history and politics. -

Descendants of Henry Reynolds

Descendants of Henry Reynolds Charles E. G. Pease Pennyghael Isle of Mull Descendants of Henry Reynolds 1-Henry Reynolds1 was born on 2 Jun 1639 in Chippenham, Wiltshire and died in 1723 at age 84. Henry married Jane1 about 1671. Jane was born about 1645 and died in 1712 about age 67. They had four children: Henry, Richard, Thomas, and George. 2-Henry Reynolds1 was born in 1673 and died in 1712 at age 39. 2-Richard Reynolds1 was born in 1675 and died in 1745 at age 70. Richard married Anne Adams. They had one daughter: Mariah. 3-Mariah Reynolds1 was born on 29 Mar 1715 and died in 1715. 2-Thomas Reynolds1 was born about 1677 in Southwark, London and died about 1755 in Southwark, London about age 78. Noted events in his life were: • He worked as a Colour maker. Thomas married Susannah Cowley1 on 22 Apr 1710 in FMH Southwark. Susannah was born in 1683 and died in 1743 at age 60. They had three children: Thomas, Thomas, and Rachel. 3-Thomas Reynolds1 was born in 1712 and died in 1713 at age 1. 3-Thomas Reynolds1,2,3 was born on 22 May 1714 in Southwark, London and died on 22 Mar 1771 in Westminster, London at age 56. Noted events in his life were: • He worked as a Linen Draper. • He worked as a Clothworker in London. Thomas married Mary Foster,1,2 daughter of William Foster and Sarah, on 16 Oct 1733 in Southwark, London. Mary was born on 20 Oct 1712 in Southwark, London and died on 23 Jul 1741 in London at age 28. -

Ucin1070571375.Pdf (2.43

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI DATE: November 10, 2003 I, Craig T. Cobane II , hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Philosophy in: Political Science It is entitled: Terrorism and Democracy The Balance Between Freedom and Order: The British Experience Approved by: Richard Harknett James Stever Thomas Moore Terrorism and Democracy The Balance Between Freedom and Order: The British Experience A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) in the Department of Political Science of the College of Arts and Sciences 2003 by Craig T. Cobane II B.S., University of Wisconsin-Green Bay 1990 M.A., University of Cincinnati 1992 Committee Chair: Richard J. Harknett, Ph.D. Abstract The British Government has been engaged for more than thirty years in a struggle with terrorism related to Northern Ireland. During what is euphemistically called the Troubles, the British government has implemented a series of special emergency laws to address the violence. Drawing upon the political context and debate surrounding the implementation and development of the emergency legislation this research examines the overall effect of British anti-terrorism legislation on both respect for civil liberties and the government’s ability to fight campaigns of violence. Drawing heavily upon primary sources, high profile cases of miscarriages of justice and accusation of an official ‘shoot to kill’ policy this project explores three distinct areas related to a government’s balancing of the exigencies of individual liberty and societal order. -

Guildford Four: Gerry Conlon's Sister Calls for Files to Be Released”

Networked Knowledge Media Reports Networked Knowledge IRA Bombing Cases Homepage This page set up by Dr Robert N Moles On 27 October 2016 Tanya Gupta of BBC News reported “Guildford Four: Gerry Conlon's sister calls for files to be released”. The sister of Guildford Four member Gerry Conlon has called for secret papers on his case to be made public after some were released to the BBC. Mr Conlon and three others were jailed in what is widely regarded as one of the UK's worst miscarriages of justice. Previously unseen files from an inquiry into the case indicate persistent attempts to try to "reconvict" the four, Mr Conlon's lawyer has said. His sister Ann McKernan said releasing the documents would reveal the truth. It was Mr Conlon's dying wish to see evidence gathered as part of an inquiry into the case made public. Following a freedom of information request, the first six files from Sir John May's five-year probe into the bombings were released to the BBC after a redaction process that took nearly a year. But the vast majority of the files - more than 700 - remain closed at the National Archives at Kew. The Guildford Four Gerry Conlon , Paddy Armstrong, Paul Hill and Carole Richardson, who always protested their innocence, served 15 years before their convictions were quashed by the Court of Appeal in 1989. All made signed confessions and were charged with the Guildford bombings, but would later retract their statements, claiming they had been obtained using violence, threats to their family and intimidation. -

Building Institutions to Address Miscarriages of Justice in England and Wales: “Mission Accomplished?”

University of Cincinnati Law Review Volume 80 Issue 4 Article 13 September 2013 Building Institutions to Address Miscarriages of Justice in England and Wales: “Mission Accomplished?” Carole McCartney Stephanie Roberts Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.uc.edu/uclr Recommended Citation Carole McCartney and Stephanie Roberts, Building Institutions to Address Miscarriages of Justice in England and Wales: “Mission Accomplished?”, 80 U. Cin. L. Rev. (2013) Available at: https://scholarship.law.uc.edu/uclr/vol80/iss4/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by University of Cincinnati College of Law Scholarship and Publications. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Cincinnati Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Cincinnati College of Law Scholarship and Publications. For more information, please contact [email protected]. McCartney and Roberts: Building Institutions to Address Miscarriages of Justice in Engla BUILDING INSTITUTIONS TO ADDRESS MISCARRIAGES OF JUSTICE IN ENGLAND AND WALES: ‘MISSION ACCOMPLISHED’? Carole McCartney* & Stephanie Roberts**† ABSTRACT The revelation of miscarriages of justice can lead a criminal justice system to a crisis point, which can be capitalized upon to engineer legal reforms. In England and Wales, these reforms have included the establishment of three bodies: the Court of Criminal Appeal, the Criminal Cases Review Commission, and the Forensic Regulator. With differing remits, these institutions are all intended to address miscarriages of justice. After outlining the genesis of these bodies, we question whether these three institutions are achieving their specific goals. This Article then outlines the benefits accrued from the establishment of these bodies and the controversies that surround their operation. -

Terrorism in London

Terrorism in London It is doubtless, that London has always been a target for political crime and assassination, just like every other major city around the globe. But there were two major terror attacks that caused a lot of tragedy and discussion. The first attacks are well-known as the “Guildford pub bombings”. It was the starting shot of the Irish Republican Army’s (IRA) bomb campaign. The two attacks occurred on the same day and were supposedly performed by the same four people who are known as the “The Guildford Four”. It was 5 th October in 1974 when the first bomb detonated at 8:30 pm in the pub “Horse and Groom” in Guildford which was very popular with military personnel. The bomb killed four soldiers and one civilian. The first detonation caused the other pubs to evacuate, which was a life-saving step, because the second detonation was just 30 minutes later in the pub “Seven Stars”. There were no injuries due to the evacuation. Just one month passed to the next attack in Woolwich on 7 th November in 1974 in the pub “Kings Arms”. The bomb caused the death of two soldiers. The police arrested four people who were convicted to be the committers of the bomb attacks (The Guildford Four). There was no evidence that those 4 persons were the committors and the police used torture methods to make the people confess the attacks. But that was not the end of the bomb campaign. 27 th January in 1975 was the last day of the bomb campaign.