Miscarriages of Justice and Exceptional Procedures in the 'War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nuala Kelly 1 December 2015

The Early Days of the ICPO A Personal Reflection Nuala Kelly 1 December 2015 Introduction As I prepared lunch for family down for the All Ireland last September, Gerry McFlynn (London ICPO) rang to ask if I would give an input at a conference to celebrate 30 years of ICPO’s work. I was honoured to be asked but suggested he approach more eloquent and central players who could speak about the history of the service. Anyway, 1 Dec seemed a long way off; Gerry said to think about it, but with his usual tenacity, was not easily fobbed off, so here I go and hope to do justice to the founders of the ICPO service, Anastasia Crickley, Breda Slattery and PJ Byrne of IECE with the support of Bobby Gilmore of the Irish Chaplaincy. It was they who faced the challenging task of responding to the courageous voice of Sr Sarah Clarke, who spoke at an IECE conference in 1983 and called on the Irish Bishops to offer pastoral support to the families of prisoners as they tried to locate family members in prisons the length and breadth of England. Anastasia and Breda with PJ’s support convened a meeting of key people and, in advance of its time before the term ‘evidence based approach’ was coined, Stasia carried out research into the needs of families with a relative imprisoned abroad - from England to USA and France to Thailand. Based on the evidence, a clear need existed for a structured service to respond to needs that were emerging in the late 70’s and early 80’s. -

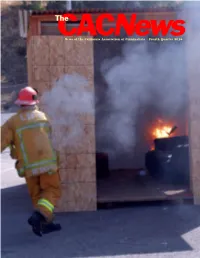

4Th Quarter 2016 and Was Highly Motivated to Seek Answers

News of the California Association of Criminalists • Fourth Quarter 2016 Making Things Happen When I was a kid, I had a poster of three baby raccoons in my room with the following quote. It is a quote that I always liked and still try to live by today. “There are people who make things happen, there are people who watch things happen, and there are people who wonder what happened.” It’s a cliché saying, but it’s also very applicable to those of us who work in forensic science. I’ve been CAC President for a few months now, so I looked back at my last address to evaluate whether I am “making things happen,” or in other words, whether I am achieving the goals I set forth at the beginning of my term. One of the goals I set forth was increasing CAC membership. Living in California is expensive, and sometimes criminalists have so many living expenses that they struggle to pay annual dues for a number of professional memberships. I found that this keeps criminalists from becoming CAC members. Therefore, I convinced my Laboratory Director to pay for an additional professional mem- bership fee for each of our criminalists. This has encouraged many more of my colleagues to join the CAC. Thank you, Ian Fitch! Now I will work to get more of these new members to attend study group meetings and seminars. Maybe I can even get one or two of them to present some of their fine work. Are any other laboratories able to dig a little deeper to find some funding to financially assist their criminalists in participating in professional activities? Another goal was to get more people to serve so that our association as a whole can “make things happen.” I have asked a lot of people to step up and serve and have only been met with enthusiasm. -

3 Failure, Guilt, Confession, Redemption? Revisiting

Journal of Psychosocial Studies Volume 10, Issue 1, May 2017 Failure, guilt, confession, redemption? Revisiting unpublished research through a psychosocial lens MARCUS FREE Abstract This article offers some critical reflections on a case of failure to bring a qualitative research project to completion and publication earlier in the author’s career. Possible explanations are considered in light of insights derived from the ‘psychosocial’ turn in qualitative research associated particularly with Hollway and Jefferson’s Doing Qualitative Research Differently (2001/2013). The project was an interview-based study of the life experiences of middle aged and older Irish emigrants in England, conducted in the late 1990s in Birmingham and Manchester. The article considers the failure as a possible psychic defence against the anxiety that completion and publication would be a betrayal of the interviewees, many of whom described experiences distressing to themselves and the interviewer. The psychoanalytic concepts of ‘transference’ and ‘countertransference’ are used to speculate as to the role of the unconscious at work in the interview encounters and how, despite class and generational differences, psychodynamic fantasies relating to both interviewees’ and interviewer’s migration histories and experiences may have impacted upon each other. Introduction Many researchers leave unfinished projects behind them and experience varying degrees of regret and uncertainty as to the reasons for reluctance or inability to bring the research to fruition. This article concerns a qualitative research project from earlier in my career that never reached completion and remains a source of guilt and shame for me. It revisits the research critically using a psychosocial lens in an attempt to identify and consider the possible underlying reasons for this failure. -

A Veritable Revolution: the Court of Criminal Appeal in English

A VERITABLE REVOLUTION: THE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEAL IN ENGLISH CRIMINAL HISTORY 1908-1958 A THESIS IN History Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS by CECILE ARDEN PHILLIPS B.A. University of Missouri-Kansas City, 1986 Kansas City, Missouri 2012 © 2012 CECILE ARDEN PHILLIPS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED A VERITABLE REVOLUTION: THE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEAL IN ENGLISH CRIMINAL HISTORY 1908-1958 Cecile Arden Phillips, Candidate for the Masters of Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2012 ABSTRACT In a historic speech to the House of Commons on April 17, 1907, British Attorney General, John Lawson Walton, proposed the formation of what was to be the first court of criminal appeal in English history. Such a court had been debated, but ultimately rejected, by successive governments for over half a century. In each debate, members of the judiciary declared that a court for appeals in criminal cases held the potential of destroying the world-respected English judicial system. The 1907 debates were no less contentious, but the newly elected Liberal government saw social reform, including judicial reform, as their highest priority. After much compromise and some of the most overwrought speeches in the history of Parliament, the Court of Criminal Appeal was created in August 1907 and began hearing cases in May 1908. A Veritable Revolution is a social history of the Court’s first fifty years. There is no doubt, that John Walton and the other founders of the Court of Criminal Appeal intended it to provide protection from the miscarriage of justice for English citizens convicted of criminal offenses. -

Socialist Lawyer 11

Summer 1990 No.11 El .50 rssN 0954 3635 HALDANE SOCIETY OF SOCIALIST LAWYERS Stephen Sedley 0C on the Judges' Role in Public Law A Revolution in Soviet Law? The Union Struggle in South Africa The Victims of FBI Frame Ups v HALDANE SOCIETY OF SOCIALIST LAYUYERS HALDANE NEWS PRESIDENT: John Platts-Mills QC Haldane News 1 AGM VICE PRESIDENTS: Kader Asmal; Fennis Augustine; Jack The Society held its AGM on 3 March 1990. Although attendance was disappointing, a number ofimportant reso- Gaster; Tony Gifford QC; Tess GilI;Jack Despatches 2 Hendy; Helena Kennedy; Dr?aul O'Higgins; lutions were passed. The Society reaffirmed its beliefin the government Albie Sachs; Stephen Sedley QC; Michael 'right to silence'and called on the to withdraw proposals Seifert; David T\rrner-Samuels QC; to limit it. The Society has done a considerable Professor Lord Wedderburn QC amount of work on electronic tagging, monitoring its use in Tower Bridge Magistrates Court. It called on the govern- Featute$ ment to abandon the scheme and to implement more con- CHAIR Bill Bowring Revolutionary Developments structive measures to reduce prison overcrowding. Resolu- tions on the Guildford Four and Birmingham Six cases were SECRETARY: Keir Starmer in Soviet Law passed, as was a proposal to campaign to amend the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Bill. The Society committed TREASURER: Robin Oppenheim Bill Bowring 4 itself to providing a forum for discussion of the issues of pornography and censorship. Two resolutions on mental MEMBERSHIP Unisex Pensions and lnsurance - health underlined our increasing work in this freld. Inter- Tony Metzer LucyAnderson nationally, the shoot to kill policy was condemned and the SEGTRETARY: and Risk Assessing the standards ofthe International Labour Organisation were Lucy Anderson 6 endorsed. -

Birmingham Six Case Shocks Britain; Some See Parallels to U.S. 'Justice'

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 18, Number 13, March 29, 1991 Birmingham Six case shocks Britain; some see parallels to U.S. Justice' by Our Special Correspondent On March 14, the Court of Appeal in London reversed the Amnesty International fraud convictions of six Irishmen, jailed for 16 years in Britain for Defense solicitors like Miss Gareth Pierce and Alistair crimes they never did commit. The men, the "Birmingham Logan worked seven days a week for over a decade, taking Six, " were accused of having set off bombs in two pubs in enormous financial losses.But Amnesty International, which Birmingham in 1974, killing 21 and wounding 162. continues to assert that there are no, political prisoners in the British Home Secretary Kenneth Baker had to announce United States, would not touch these Irish cases in its own in Parliament after the reversal that a Royal Commission frontyard-Amnesty is based in London-untila press cam will examine the entire British criminal justice system. All paign by the defense lawyers made the thing so hot they could recent major prosecutions of IRA "terrorists " have been no longer afford to stay out of it. overturned. Amnesty has also refused to touch the case of Lyndon Back in 1974, England was swept by a lynch mob mood LaRouche until now, calling it "not:political, " but, in a letter like that among Americans today when they hear the word we excerpt here, an English lawyer familiar with both cases "Iraq." Six unfortunate Irishmen were arrested at Liverpool, says they are both political frameups. -

The Future of Adversarial Criminal Justice in 21St Century Britain

NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW Volume 35 Number 2 Article 3 Winter 2010 The Future of Adversarial Criminal Justice in 21st Century Britain Jacqueline S. Hodgson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj Recommended Citation Jacqueline S. Hodgson, The Future of Adversarial Criminal Justice in 21st Century Britain, 35 N.C. J. INT'L L. 319 (2009). Available at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol35/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Future of Adversarial Criminal Justice in 21st Century Britain Cover Page Footnote International Law; Commercial Law; Law This article is available in North Carolina Journal of International Law: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol35/ iss2/3 The Future of Adversarial Criminal Justice in 21st Century Britain Jacqueline S. Hodgson t I. Introduction ....................................................................... 3 19 II. England and Wales: A Mixed System with Adversarial R oots .................................................................................. 320 III. Miscarriages of Justice: The Royal Commission on Criminal Justice and System Rebalancing ........................ 325 IV. The Defense Under Attack ................................................ 331 V. The Rise -

Maudsley Discussion Paper No. 2

Maudsley Discussion Paper No. 2 DISPUTED CONFESSIONS AND THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM Gisli H. Gudjonsson & James MacKeith Institute of Psychiatry, London MAUDSLEY DISCUSSION PAPER NO. 2 Disputed confessions and the Criminal Justice System Gisli H. Gudjonsson and James MacKeith. Institute of Psychiatry, London. ABSTRACT This paper outlines the contributions that forensic psychology and psychiatry have made in recent years to the understanding of ‘unreliable’ confessions. There is now an improved scientific base from which experts can testify in cases of disputed con- fessions. The status of the expert in these cases is no longer in dispute. The Courts increasingly rely on expert testimony. What is controversial is the nature of the expert’s contribution in judicial proceedings. The authors argue that expert testimony is sometimes inappropriately applied to cases and misused by the legal profession to attempt an acquittal. While the Courts should accept that psychological vulnerabilties and mental disorder can in certain circumstances result in unreliable confessions, the testimony of experts must be scrupulously balanced and be open to careful scrutiny. Extra copies of this discussion paper may be obtained from Mr Paul Clark, Institute of Psychiatry, de Crespigny Park, London SE5 8AF for £2.95 including post and packing. 1 Introduction English criminal law recognises that confessions made by mentally ill defendants need to be treated with special caution. In such cases psychiatrists and psychologists commonly provide advice to the Courts. Over the last sixteen years clinical and research work based in the Institute of Psychiatry has made an important contribution to the understanding of how the reliability of testimony can be evaluated in cases where confessions are disputed. -

Ucin1070571375.Pdf (2.43

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI DATE: November 10, 2003 I, Craig T. Cobane II , hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Philosophy in: Political Science It is entitled: Terrorism and Democracy The Balance Between Freedom and Order: The British Experience Approved by: Richard Harknett James Stever Thomas Moore Terrorism and Democracy The Balance Between Freedom and Order: The British Experience A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) in the Department of Political Science of the College of Arts and Sciences 2003 by Craig T. Cobane II B.S., University of Wisconsin-Green Bay 1990 M.A., University of Cincinnati 1992 Committee Chair: Richard J. Harknett, Ph.D. Abstract The British Government has been engaged for more than thirty years in a struggle with terrorism related to Northern Ireland. During what is euphemistically called the Troubles, the British government has implemented a series of special emergency laws to address the violence. Drawing upon the political context and debate surrounding the implementation and development of the emergency legislation this research examines the overall effect of British anti-terrorism legislation on both respect for civil liberties and the government’s ability to fight campaigns of violence. Drawing heavily upon primary sources, high profile cases of miscarriages of justice and accusation of an official ‘shoot to kill’ policy this project explores three distinct areas related to a government’s balancing of the exigencies of individual liberty and societal order. -

Irish Catholics in British Courts: an American Judicial Perspective of the Gilbert ("Danny") Mcnamee Trial

NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law Volume 11 Number 1 IRELAND: RECENT DEVELOPMENTS Article 5 1990 IRISH CATHOLICS IN BRITISH COURTS: AN AMERICAN JUDICIAL PERSPECTIVE OF THE GILBERT ("DANNY") MCNAMEE TRIAL Andrew L. Somers Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/ journal_of_international_and_comparative_law Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Somers, Andrew L. (1990) "IRISH CATHOLICS IN BRITISH COURTS: AN AMERICAN JUDICIAL PERSPECTIVE OF THE GILBERT ("DANNY") MCNAMEE TRIAL," NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law: Vol. 11 : No. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/journal_of_international_and_comparative_law/vol11/iss1/ 5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. IRISH CATHOLICS IN BRITISH COURTS: AN AMERICAN JUDICIAL PERSPECTIVE OF THE GILBERT ("DANNY") MCNAMEE TRIAL ANDREW L. SOMERS * I. INTRODUCTION In August 1986, Gilbert "Danny" McNamee travelled on a daily basis from his home in Crossmaglen, Northern Ireland, to his place of employment at an electronics shop in Dundalk, Southern Ireland.' He lived peacefully in Crossmaglen until that night in August when British Special Air Services (SAS) soldiers arrested him at his flat.' For two days he was detained in Armagh, Northern Ireland, suspected of being in possession of information relating to terrorist crimes in the United Kingdom.3 He then was whisked to a London police station where he was charged with conspiracy to cause explosions.' For over one year, he and his lawyer were led to believe that he would answer for some fingerprints found on bomb fragments and on electronics equipment discovered in three Irish Republican Army (IRA) bomb caches unearthed in Britain.5 Two weeks before trial began, the Queen's forces decided to add the Hyde Park bombing incident to the conspiracy with which he was charged. -

Building Institutions to Address Miscarriages of Justice in England and Wales: “Mission Accomplished?”

University of Cincinnati Law Review Volume 80 Issue 4 Article 13 September 2013 Building Institutions to Address Miscarriages of Justice in England and Wales: “Mission Accomplished?” Carole McCartney Stephanie Roberts Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.uc.edu/uclr Recommended Citation Carole McCartney and Stephanie Roberts, Building Institutions to Address Miscarriages of Justice in England and Wales: “Mission Accomplished?”, 80 U. Cin. L. Rev. (2013) Available at: https://scholarship.law.uc.edu/uclr/vol80/iss4/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by University of Cincinnati College of Law Scholarship and Publications. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Cincinnati Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Cincinnati College of Law Scholarship and Publications. For more information, please contact [email protected]. McCartney and Roberts: Building Institutions to Address Miscarriages of Justice in Engla BUILDING INSTITUTIONS TO ADDRESS MISCARRIAGES OF JUSTICE IN ENGLAND AND WALES: ‘MISSION ACCOMPLISHED’? Carole McCartney* & Stephanie Roberts**† ABSTRACT The revelation of miscarriages of justice can lead a criminal justice system to a crisis point, which can be capitalized upon to engineer legal reforms. In England and Wales, these reforms have included the establishment of three bodies: the Court of Criminal Appeal, the Criminal Cases Review Commission, and the Forensic Regulator. With differing remits, these institutions are all intended to address miscarriages of justice. After outlining the genesis of these bodies, we question whether these three institutions are achieving their specific goals. This Article then outlines the benefits accrued from the establishment of these bodies and the controversies that surround their operation. -

Judith Ward Has Her Case Referred to the Court of Appeal

On the road to freedom? Britain's claim exposed: Uncovering the Irish roots of one Judith Ward has her case why we need to campaign to of the great families of referred to the Court of Appeal repeal Article 75 English literature !• 11111111111111111111111 in 111 ii 1111111111111M11111 § § 111 * 111 • • w r i 2-SEPI991 Founded 1939 Hon: campaigning for a united and independent Ireland September 1991 union: internal education is to be developed, guidelines for raising the issue at regional and national TUCs produced and links forged at every level with NALGO's sister unions - NIPSA in the north, LGPSU in the south. But while the NALGO resolution is a model attempt to advance pre- viously existing policy, the TGWU resolution shows what can be done in a union which has fought Turn to page 2 U1LDING I site bosses •K whose ne- •fgligence Rl^r causes work- place deaths should face police investiga- tions and manslaughter charges according to the big- gest construction workers' union, UCATT. Last month the union announced it was seeking a meeting with police chiefs to discuss much tougher action following work- place deaths, including-im- prisonment of SB Mzw 'v. NEWS NEWS Trade unions must taride Ireland Innocent victim Peace Train job with Chipperfields circus. those who dare voice dissent bomb-planter". She of course concerning the M62 bombing. PETER MULUGAN examines She left them on 5 February against Britain's policy in Ire- denied the contents of her en- The prosecution also added From page 1 development and transport 1974 to stay with friends in land.