Convicting the Innocent: a Triple Failure of the Justice System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Sweeney Investigative Journalist, BBC Panorama

John Sweeney Investigative journalist, BBC Panorama Media Masters – November 23, 2015 Listen to the podcast online, visit www.mediafocus.org.uk Welcome to Media Masters, a series of one to one interviews with those at the top of the media game. Today I’m joined by the writer and broadcaster John Sweeney. John is known for his in-depth investigative journalism and sometimes literally explosive documentaries. Now working with BBC Panorama, he reported for 12 years at the Observer, where he covered wars and chaos in more than 60 countries. His reports challenging the expert evidence of Professor Roy Meadow helped free cot death mum Sally Clark and six others, and led to him winning the first Paul Foot award. He has gone undercover in Chechnya, Zimbabwe and North Korea, where he posed as a professor. He famously lost his temper with the Church of Scientology after they harassed and spied on his team, and he challenged Vladimir Putin in Siberia over the war in Ukraine, and this year has reported on the refugee crisis and the Paris massacre. John, thanks for joining me. Hi, Paul. Shall we go straight into the Paris massacre, then? Because you’ve just literally got back from there. Well, yes. It’s a Friday night, I’m in the pub, I’ve had a few beers. I’m not catatonically out of it with alcohol, but I’m pretty drunk. Merry. Merry. And the deputy editor of Panorama phones, there’s been a lot dead in Paris… first train in the morning, couple of hours’ sleep, and it’s not proper sleep, and you hit it, and we go to this little… the Rue Alibert… and after I left LSE I worked for a photo agency in Paris for a month, so I don’t know the city well, but I love it. -

Chapter 2 International Perspectives on Wrongful

CHAPTER 2 INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES ON WRONGFUL CONVICTION 2.1 Introduction Judicial Error or miscarriage of justice will ―invariably identify at least some element of an earlier conviction as a mistake: whether evidential, procedural or material irregularity‖. - Edmond73 Wrongful conviction, as a major concern, was recognized initially in the United States beginning in the early 1930s. The subject of wrongful conviction caught the public and scholarly attention primarily based on individual cases in the U.S.; including cases like the ―Dreyfus affair in the nineteenth century, the infamous case of the ‗Scottsboro boys‘ in te 1920s, the case of Randall Dale Adams, Sam Sheppard case, the ‗Birmingham Six‘ case and the wrongful conviction of Michael and Lindy Chamberlain for the death of their daughter in Australia‖74 These cases had attracted much public attention due to the injustice suffered by the innocents and their families. Several books, article and research papers focussed on these cases, providing reasons and suggestions for the same. This led to exonerations of most of the cases that came under media limelight, where the jury was compelled to reconsider the facts and decide the case thoughtfully based on correct evidence. Most of the people who got exonerated, were sentenced to death. The exoneration of the wrongfully convicted individuals was, indeed, the major factor for identification of wrongful conviction as an impediment to criminal justice system. Numerous reasons can be attributed to the exonerations of individuals. The progress and development made in the field of forensic science such as the DNA testing of the evidence has contributed immensely to the convictions being overturned. -

A Critical Analysis of Medical Opinion Evidence in Child Homicide Cases

A critical analysis of medical opinion evidence in child homicide cases Sharmila Betts B.A. (Hons.), University of Sydney, 1985 M. Psychol., University of Sydney, 1987 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Law, The University of New South Wales (Sydney). i ii iii Acknowledgements No way of thinking or doing, however ancient, can be trusted without proof. Henry David Thoreau I am a Clinical Psychologist practicing since 1987. My time at a tertiary level Child Protection Team at The Sydney Children’s Hospital, Randwick, Australia brought to my attention the pivotal role of medical opinion evidence in establishing how children sustained injuries, which were sometimes fatal. This thesis began in a Department of Psychology, but I transferred to a Law Faculty. Though I am not a lawyer, the thesis endeavours to examine medico-legal and psychological aspects of sudden unexplained infant deaths. It sets itself the task of addressing important questions requiring rigorous and critical analysis to ensure accuracy and justice is achieved. I hope my thesis sheds light on this complex issue. Gary Edmond has been a mentor, guide and staunch critic. I am deeply grateful that he trusted a novice to navigate this perplexing field of inquiry. Emma Cunliffe has provided clarity in an area shrouded in uncertainty. Their patience, support and faith have enabled me to crystalise and formulate my fledgling insights into a dissertation. I am indebted to Natalie Tzovaras, Monique Ross, Katie Poidomani, and Janet Willinge for their administrative support. My husband, Grant, posed the question that started my journey - ‘how do doctors know the injuries were deliberately inflicted?’ Through my many doubts and fears, he iv maintained a trust in my ability to address this question and helped me return time and again to the seemingly overwhelming task before me. -

Probability, Justice, and the Risk of Wrongful Conviction

The Mathematics Enthusiast Volume 12 Number 1 Numbers 1, 2, & 3 Article 5 6-2015 Probability, Justice, and the Risk of Wrongful Conviction Jeffrey S. Rosenthal Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/tme Part of the Mathematics Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Rosenthal, Jeffrey S. (2015) "Probability, Justice, and the Risk of Wrongful Conviction," The Mathematics Enthusiast: Vol. 12 : No. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/tme/vol12/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Mathematics Enthusiast by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TME, vol. 12, no. 1,2&3, p. 11 Probability, Justice, and the Risk of Wrongful Conviction Jeffrey S. Rosenthal University of Toronto, Canada Abstract: We consider the issue of standards of proof in legal decisions from the point of view of probability. We compare ``balance of probabilities'' and ``beyond a reasonable doubt'' to the statistical use of p-values. We point out various fallacies which sometimes arise in legal reasoning. And we provide several examples of legal cases which involved probabilities, including some in which incorrect decisions were made and defendants were wrongfully convicted. Keywords: probability, statistics, p-value, balance of probabilities, beyond a reasonable doubt, standard of proof. Background and Context I am a professor of statistics, and most of my work is fairly technical and mathematical (see www.probability.ca/jeff/research.html). -

4Th Quarter 2016 and Was Highly Motivated to Seek Answers

News of the California Association of Criminalists • Fourth Quarter 2016 Making Things Happen When I was a kid, I had a poster of three baby raccoons in my room with the following quote. It is a quote that I always liked and still try to live by today. “There are people who make things happen, there are people who watch things happen, and there are people who wonder what happened.” It’s a cliché saying, but it’s also very applicable to those of us who work in forensic science. I’ve been CAC President for a few months now, so I looked back at my last address to evaluate whether I am “making things happen,” or in other words, whether I am achieving the goals I set forth at the beginning of my term. One of the goals I set forth was increasing CAC membership. Living in California is expensive, and sometimes criminalists have so many living expenses that they struggle to pay annual dues for a number of professional memberships. I found that this keeps criminalists from becoming CAC members. Therefore, I convinced my Laboratory Director to pay for an additional professional mem- bership fee for each of our criminalists. This has encouraged many more of my colleagues to join the CAC. Thank you, Ian Fitch! Now I will work to get more of these new members to attend study group meetings and seminars. Maybe I can even get one or two of them to present some of their fine work. Are any other laboratories able to dig a little deeper to find some funding to financially assist their criminalists in participating in professional activities? Another goal was to get more people to serve so that our association as a whole can “make things happen.” I have asked a lot of people to step up and serve and have only been met with enthusiasm. -

A Veritable Revolution: the Court of Criminal Appeal in English

A VERITABLE REVOLUTION: THE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEAL IN ENGLISH CRIMINAL HISTORY 1908-1958 A THESIS IN History Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS by CECILE ARDEN PHILLIPS B.A. University of Missouri-Kansas City, 1986 Kansas City, Missouri 2012 © 2012 CECILE ARDEN PHILLIPS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED A VERITABLE REVOLUTION: THE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEAL IN ENGLISH CRIMINAL HISTORY 1908-1958 Cecile Arden Phillips, Candidate for the Masters of Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2012 ABSTRACT In a historic speech to the House of Commons on April 17, 1907, British Attorney General, John Lawson Walton, proposed the formation of what was to be the first court of criminal appeal in English history. Such a court had been debated, but ultimately rejected, by successive governments for over half a century. In each debate, members of the judiciary declared that a court for appeals in criminal cases held the potential of destroying the world-respected English judicial system. The 1907 debates were no less contentious, but the newly elected Liberal government saw social reform, including judicial reform, as their highest priority. After much compromise and some of the most overwrought speeches in the history of Parliament, the Court of Criminal Appeal was created in August 1907 and began hearing cases in May 1908. A Veritable Revolution is a social history of the Court’s first fifty years. There is no doubt, that John Walton and the other founders of the Court of Criminal Appeal intended it to provide protection from the miscarriage of justice for English citizens convicted of criminal offenses. -

Capital Punishment at Home and Abroad: A

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Honors Theses Student Scholarship Fall 2015 Capital Punishment at Home and Abroad: A Comparative Study on the Evolution of the Use of the Death Penalty in the United States and the United Kingdom Rachel Gaines Eastern Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/honors_theses Recommended Citation Gaines, Rachel, "Capital Punishment at Home and Abroad: A Comparative Study on the Evolution of the Use of the Death Penalty in the United States and the United Kingdom" (2015). Honors Theses. 293. https://encompass.eku.edu/honors_theses/293 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i EASTERN KENTUCKY UNIVERSITY Capital Punishment at Home and Abroad: A Comparative Study on the Evolution of the Use of the Death Penalty in the United States and the United Kingdom Honors Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements of HON 420 Fall 2015 By Rachel Gaines Faculty Mentor Dr. Sucheta Mohanty Department of Government ii Capital Punishment at Home and Abroad: A Comparative Study on the Evolution of the Use of the Death Penalty in the United States and the United Kingdom Rachel Gaines Faculty Mentor Dr. Sucheta Mohanty, Department of Government Abstract: Capital punishment (sometimes referred to as the death penalty) is the carrying out of a legal sentence of death as punishment for crime. The United States Supreme Court has most recently ruled that capital punishment is not unconstitutional. -

Introduction Several High‐Profile Criminal Cases, Such As Those Of

Introduction Several high‐profile criminal cases, such as those of Sally Clark, Angela Cannings, Trupti Patel and Donna Anthony – all wrongly convicted of the murder of their children on the basis of flawed expert evidence – have raised serious questions about the use, nature and quality of expert evidence in such cases. As well as the injustice and suffering inflicted on innocent families, the publicity surrounding these cases has seriously undermined public confidence in the criminal justice system. Further, this publicity has deterred suitably qualified clinicians, already in short supply, from acting as expert witnesses. In the wake of these cases, the government commissioned the Chief Medical Officer, Sir Liam Donaldson, to produce proposals for the reform of expert evidence in family law cases more generally. Such reform was long overdue since there were already serious concerns about unacceptable delays in cases where experts were instructed. These delays were attributed partly to a significant increase in the number of experts being instructed, their limited availability for hearings and the late submission of reports to the court. Such issues are addressed in the Report from Sir Liam Donaldson on this issue, which concentrates on public law proceedings in Children Act cases and makes 16 proposals for reform. As the Report makes clear, the issues raised are relevant to medical evidence in both criminal and Children Act cases. Research cited in the report shows that there have been surprisingly few instances in family law cases where the evidence of expert witnesses has been disputed. The Minister for Children had required local authorities to review cases of children who were the subject of care proceedings where certain expert evidence was likely to have had a significant bearing upon the decisions of the courts. -

Sudden Infant Death Or Murder? a Royal Confusion About Probabilities Neven Sesardic

Brit. J. Phil. Sci. 58 (2007), 299–329 Sudden Infant Death or Murder? A Royal Confusion About Probabilities Neven Sesardic ABSTRACT In this article I criticize the recommendations of some prominent statisticians about how to estimate and compare probabilities of the repeated sudden infant death and repeated murder. The issue has drawn considerable public attention in connection with several recent court cases in the UK. I try to show that when the three components of the Bayesian inference are carefully analyzed in this context, the advice of the statisticians turns out to be problematic in each of the steps. 1 Introduction 2 Setting the Stage: Bayes’s Theorem 3 Prior Probabilities of Single SIDS and Single Homicide 4 Prior Probabilities of the Recurrence of SIDS and Homicide 5 Likelihoods of Double SIDS and Double Homicide 6 Posterior Probabilities of Double SIDS and Double Homicide 7 Conclusion 1 Introduction There has been a lot of publicity recently about several women in the United Kingdom who were convicted of killing their own children after each of these mothers had two or more of their infants die in succession and under suspicious circumstances. (A few of these convictions were later overturned on appeal.) The prosecutor’s argument and a much discussed opinion of a crucial expert witness in all these court cases relied mainly on medical evidence but a probabilistic reasoning also played a (minor) role. It was this latter, probabilistic aspect of the prosecutor’s case that prompted a number of statisticians to issue a general warning about what they regarded The Author (2007). -

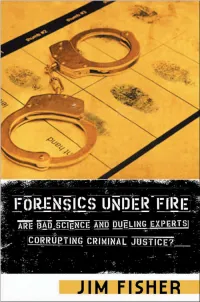

Forensics Under Fire.Pdf

Prelims.qxd 11/14/07 2:28 PM Page i Forensics under Fire Prelims.qxd 11/14/07 2:28 PM Page ii Prelims.qxd 11/14/07 2:28 PM Page iii ≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈ Forensics under Fire Are Bad Science and Dueling Experts Corrupting Criminal Justice? JIM FISHER ≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈≈ RUTGERS UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW BRUNSWICK, NEW JERSEY, AND LONDON Prelims.qxd 11/14/07 2:28 PM Page iv LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Fisher, Jim, – Forensics under fire : are bad science and dueling experts corrupting criminal justice? / Jim Fisher. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒‒ (hardcover : alk. paper) . Criminal investigation—United States. Crime scene searches—United States. Forensic sciences—United States. Evidence, Criminal—United States I. Title. HV.F .—dc CIP A British Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the British Library. Copyright © by Jim Fisher All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Please contact Rutgers University Press, Joyce Kilmer Avenue, Piscataway, NJ –. The only exception to this prohibition is “fair use” as defined by U.S. copyright law. Visit our Web site: http://rutgerspress.rutgers.edu Manufactured in the United States of America Prelims.qxd 11/14/07 2:28 PM Page v It is through clues that we form our opinion about the facts of a case. There is only one alternative: to catch the culprit red-handed. —Theodore Reik, The Compulsion to Confess, 1959 Clues are tangible signs which prove—or seem to prove—that no crime can be committed by thought only and that we live in a world regulated by mechanical laws. -

Building Institutions to Address Miscarriages of Justice in England and Wales: “Mission Accomplished?”

University of Cincinnati Law Review Volume 80 Issue 4 Article 13 September 2013 Building Institutions to Address Miscarriages of Justice in England and Wales: “Mission Accomplished?” Carole McCartney Stephanie Roberts Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.uc.edu/uclr Recommended Citation Carole McCartney and Stephanie Roberts, Building Institutions to Address Miscarriages of Justice in England and Wales: “Mission Accomplished?”, 80 U. Cin. L. Rev. (2013) Available at: https://scholarship.law.uc.edu/uclr/vol80/iss4/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by University of Cincinnati College of Law Scholarship and Publications. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Cincinnati Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Cincinnati College of Law Scholarship and Publications. For more information, please contact [email protected]. McCartney and Roberts: Building Institutions to Address Miscarriages of Justice in Engla BUILDING INSTITUTIONS TO ADDRESS MISCARRIAGES OF JUSTICE IN ENGLAND AND WALES: ‘MISSION ACCOMPLISHED’? Carole McCartney* & Stephanie Roberts**† ABSTRACT The revelation of miscarriages of justice can lead a criminal justice system to a crisis point, which can be capitalized upon to engineer legal reforms. In England and Wales, these reforms have included the establishment of three bodies: the Court of Criminal Appeal, the Criminal Cases Review Commission, and the Forensic Regulator. With differing remits, these institutions are all intended to address miscarriages of justice. After outlining the genesis of these bodies, we question whether these three institutions are achieving their specific goals. This Article then outlines the benefits accrued from the establishment of these bodies and the controversies that surround their operation. -

Guildford Pub Bombs: Conlons' Fight Continues After Sister's Death’

Networked Knowledge Media Reports Networked Knowledge IRA Bombing Cases Homepage This page set up by Dr Robert N Moles [Underlining, where it occurs is for NetK editorial emphasis] On 5 April 2018 Tanya Gupta of the BBC reported ‘Guildford pub bombs: Conlons' fight continues after sister's death’ Ann McKernan told the BBC in 2016 that hundreds of closed files still needed to be made public. The family of Gerry Conlon, one of 11 people wrongly convicted for the 1974 Guildford pub bombings, have vowed to continue their fight for justice following the death of his sister. Ann McKernan, 58, who led the family's campaign, died in Belfast on Monday. A pre-inquest review (PIR) into the Guildford bombings is due to be held this year after the original inquest in the 1970s never concluded. Mrs McKernan's sister Bridie Brennan will now take the lead for the family. Lawyers from KRW Law, who applied for the PIR on behalf of Mrs McKernan and a survivor after the BBC viewed official papers on the case, confirmed they now represent Ms Brennan. 'Inspirational' Mrs McKernan, who died at home surrounded by her four daughters, saw both her brother Gerry and her father Patrick "Guiseppe" Conlon jailed over the bombings which killed five and injured 65. Patrick Conlon was one of the Maguire Seven, convicted on explosives charges, and his son was one of the Guildford Four jailed for murder. All 11 eventually had their convictions quashed, but Gerry Conlon served 15 years in prison and his father died four years into his 12-year prison term.