Scruggs Keith Tuners D-Tuner Interview Transcript Bill Keith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jim-Rooney-Daa-Induction-By-Menius

Jim Rooney DAA Presentation by Art Menius IBMA World of Bluegrass Awards Luncheon September 29, 2016 Jim Rooney did me a big favor, writing. In It for the Long Run: A Musical Memoir, so that I could do this presentation. That’s being a friend. Jim is a man who has done it all while enjoying being in it for the long run in many relationships. Think of Bill Keith, Eric von Schmidt, or his eventual spouse Carol Langstaff. At Owensboro I remember Jim, tall and commanding, as his left hand powered the rhythm on a kick ass rendition of Six White Horses.” Not that he limited himself to Monroe covers. His interpretation of the Stones’ “No Expectations” became a go to song. His love for bluegrass began back in Massachusetts in the 1950s when he heard on a band called the Confederate Mountaineers at radio station WCOP. Inspired by the Lillys, Tex, and Stovepipe, it wasn’t too long before Jim was on WCOP himself and hooked on performing. At Amherst he met Bill Keith who would be a friend and musical partner for much of the next 60 years. In 1962, they recorded “Devils Dream” and “Sailor’s Hornpipe,” the first documentation of Bill’s chromatic style shortly before he joined the Blue Grass Boys. The tracks appeared on their Living on the Mountain LP. Their many collaborations would include the revolutionary Blue Velvet Band whose music spread worldwide person to person Mud Acres, and concerts and tours with many different aggregations and combinations. Jim enjoyed sharing a heritage award from the Boston Bluegrass Union and brought us to tears at Bill’s induction into the Hall of Fame. -

The World Before Scruggs

THE WORLD BEFORE SCRUGGS "Try to imagine the world before Earl Scruggs -- it's unbelievable!" This exclamation by Rick was how our May, 1985 talks began, and it offers a keynote for his music and his thinking. To hear this makes you realize there's a lot more to Rick Shubb than "the guy who makes those capos." Still, one little invention has made Rick's name a musical household word: the ingenious and beauti- ful guitar (and banjo) capo known, simply, as the Shubb capo. Actually, Rick's other products include the innovative Shubb banjo fifth-string sliding capo, the Shubb compensated banjo bridge, the Shubb- Pearse steel (a distinctive bar for Dobro and steel guitar), a pickup and amplifier designed specifically for the banjo (no longer on the market). Most recently, his aptitude for computer database develop- ment has led him to produce a line of computer software for musicians.The first in this line is SongMaster, which will keep track of your songs, followed by GigMaster, a booking tool for musi- cians. Both are easy and affordable, and now available. But the guitar capo in particular has really put his name on the map. A Profile of Rick Shubb By Sandy Rothman Yet, Rick's part in the history of bluegrass in college towns like Berkeley, riding the and became aware of the Ramblers, music in California and the Bay Area long crest of the folk revival. With the forma- eventually taking one banjo lesson from preceded his emergence as a businessman tion of the Redwood Canyon Ramblers, a Neil Rosenberg. -

Bomnewsletter #275 今月の注目!

B.O.M.Newsletter #275 CR-0236 V.A.『Autoharp Legacy』CD3枚 組¥3,750- 2003年9月9日記 オートハープ 物の決定盤!!詳細はインスト新入荷参 8月も終わりになって突然の真夏がやってきたり、天 照。 候も体調も狂いがちな夏も終わり、秋です。…芸術の秋、 ACD-54 SAM BUSH & DAVID GRISMAN ブルーグラスの秋です。アコースティック楽器が天高く 『Hold On, We’re Strummin’』CD¥2,750- 響きます。 ホンマ、天気も経済も、政治も社会も…、 長らく噂のサム&デイブ、遂に発表です。詳細はブル 何か乱調気味の今日この頃、自分が一生懸命になれるも ーグラス新入荷参照。 のを持っている我々は幸せなのかもしれません。音楽は、 PATUX-075 FRANK WAKEFIELD『Don’t それもルーツに根ざしたヒトに近い音楽は、決して裏切 Lie To Me』CD¥2,750- りません。アコースティック楽器は(歌も含め)、真心 天才マンドリニスト、フランク・ウェイクフィールド を込めて、一生懸命になって弾かないと、絶対にいい音 の最新作。 がしません。テクニックの問題ではありません、…気持 DUAT-1142 JUNE CARTER CASH ちです。 今年の秋も、滋賀、水戸、長崎、福島、茨城、 『Wildwood Flower』CD¥2,750- 福岡、愛媛など、全国各地でフェスが続きます。我々の 主催する『宝塚秋のブルーグラス・フェス』は10月25 5月に急逝したジューン(ムーンシャイナー6月号特 日から26日に、夏フェスと同じ三田アスレチック 集)文句なしのカーター・ファミリー・トリビュート、 (0795-69-0024)でノンビリと開きます。その他、全国 詳細はオールドタイム&フォーク新入荷参照。 各地のイベントなど、ムーンシャイナー誌をご覧くださ KOCH-6156D V.A.『Tribute to Bill Monroe; い。…もっと、楽しもう。 Legend Lives On』DVD2枚組¥3,950- KOCH-6156V VHS ¥3,950- 9月29日から10月7日までルイビルで行われるIBMA 1996年9月9日にビル・モンローが他界してから半 WORLD OF BLUEGRASS 参加のため休みます。その 年後、主を失ったブルー・グラス・ボーイズを中心に催 間、出荷やお電話での御返事が出来ませんがよろしくお された『ビル・モンロー追悼コンサート』を収めた2時 願いします。 間半!映像新入荷参照。 今月の注目!新入荷 ブルーグラス新入荷 RC-120 TIPTON HILL BOYS『 Lucky』 RC-120 TIPTON HILL BOYS『 Lucky』 CD¥2,750- CD¥2,750- 我がB.O.M.サービスのレーベル、レッド・クレイ・レ Steamboat Whistle Blues/Rosie Bokay/Lonesome コードからの最新作は、クリス・シャープからの第2弾。 Road Blues/Hot Corn Cold Corn/We All Smell ブルーグラスとクラシック・カントリーでヒルビリーを Good/Crawdad Song/What a Friend We 強く意識したティプトン・ヒル・ボーイズのデビュー Have/Danny Boy 他全16曲 作。詳細はブルーグラス新入荷参照。 我がB.O.M.サービスのレーベル、レッド・クレイ・ 1 レコードからの ビー・オズボーンをはじめ、偉大なテクニック変革者は -

Report Stephen Bruton Stephen Bruton

Mountainview Publishing, LLC INSIDE the Straight Talk from a Guitarist’s The Player’s Guide to Ultimate Tone TM Guitarist... $10.00 US, November, 2002/VOL.4 NO.1 Report Stephen Bruton Stephen Bruton 11 Welcome to the Third Anniversary Issue of TQR. We’d like to begin this month’s trip by sending our sincere thanks and appreciation to each and every one of you for granting us the privilege of PRS Goldtops, guiding and inspiring you in your ongoing love affair with the guitar. It’s you who make our The Emerald Gem, monthly Quest for Tone possible, and that’s a fact we never forget. ell, Amigos, we’re still in Texas, and we’re and a Confession kickin’ off this issue with a true guitarist’s W guitarist – Mr. Stephen Bruton of Austin, Texas. The All Music Guide (www.allmusic.com) con- from The Temple cisely describes Bruton’s tone as “reflective, wist- ful, bittersweet, rollicking and earnest.” All true, but there’s much more to consider here... Bruton grew up in Fort Worth, the son of a jazz drum- 13 mer and record store owner. The significance of these simple twists of fate are not lost on Blackbox Effects... Mr. Bruton. During the 1960s, Fort Worth’s Jacksboro Highway was a guitar player’s paradise – a melting pot of musical styles More Worthy Tone and dicey nightlife that produced an uncan- ny number of top notch, A-team session Gizmos from The players and touring pros like Bruton, T Bone Burnett, Bill Ham, Mike O’Neill, Land of a James Pennebaker, Buddy Whittington, Bob Wills, King Thousand Lakes! Curtis, Cornell Dupree, and Delbert McClinton. -

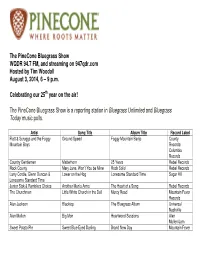

The Pinecone Bluegrass Show WQDR 94.7 FM, and Streaming on 947Qdr.Com Hosted by Tim Woodall August 3, 2014, 6 – 9 P.M

The PineCone Bluegrass Show WQDR 94.7 FM, and streaming on 947qdr.com Hosted by Tim Woodall August 3, 2014, 6 – 9 p.m. Celebrating our 25 th year on the air! The PineCone Bluegrass Show is a reporting station in Bluegrass Unlimited and Bluegrass Today music polls. Artist Song Title Album Title Record Label Flatt & Scruggs and the Foggy Ground Speed Foggy Mountain Banjo County Mountain Boys Records/ Columbia Records Country Gentlemen Matterhorn 25 Years Rebel Records Rock County Mary Jane, Won’t You be Mine Rock Solid Rebel Records Larry Cordle, Glenn Duncan & Lower on the Hog Lonesome Standard Time Sugar Hill Lonesome Standard Time Junior Sisk & Ramblers Choice Another Man’s Arms The Heart of a Song Rebel Records The Churchmen Little White Church in the Dell Mercy Road Mountain Fever Records Alan Jackson Blacktop The Bluegrass Album Universal Nashville Alan Mullen Big Mon Heartwood Sessions Alan Mullen/Jam Sweet Potato Pie Sweet Blue Eyed Darling Brand New Day Mountain Fever Records Ricky Skaggs You Can’t Hurt Ham Music to My Ears Skaggs Family Records The Osborne Brothers Rocky Top High Lonesome: The Story of Bluegrass CMH Records Music (Various Artists) (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) Old and In the Way Knockin’ on Your Door Old and In the Way Arista Lorraine Jordan & Carolina Road That’s Kentucky Lorraine Jordan & Carolina Road Pinecastle Records Randy Kohrs Devil of the Trail Quicksand Rural Rhythm Records IIIrd Tyme Out Out of Sight, Out of Mind John & Mary Rounder J.D. Crowe Philadelphia Lawyer Bluegrass Holiday Rebel Records J.D. -

Bill Keith Patron of Bluegrass, but the Idea Was Put on in Northern Kentucky

Fall November Edition 2015 Jerry Schrepfer Editor Fall November Edition Northern Kentucky Bluegrass Music Association 2015 Keeping Bluegrass Music Alive in the Northern Kentucky Area In This Edition “Buicks and Bluegrass were a Perfect Match ” Ron Simmons & Jerry Schrepfer If General Motors ever knew how good the So,with that in mind, Ron got on the internet live Bluegrass Music was at the Buick in a chat room somewhere in that great ether dealership in Florence, KY, in the early part in the sky and had a person named Jim of the new millennium it might have become Moore answer his call to pick. The two men commonplace all over the country! As a got together and made up some flyers to pass Page 1 - 4 - Third of matter of fact the Buick dealership on out. Some went to Gene Thompson’s jam A Series of Articles KY18, skippered by a gentleman named session in Hebron and soon Gene was on the About the History of Willie Roberts, was proof that it isn’t the bandwagon as well. Bluegrass Jams in place where you pick and grin, it’s the Northern Kentucky The repair bay for the Buick dealership Including Photos! people, the food and the hospitality. Most folks don’t think of a car dealership as a became one of the biggest jamming rooms Page 5 - Bill Keith patron of Bluegrass, but the idea was put on in Northern Kentucky. Tuesday night jams In Memorium the table by Ron Cornett, who was the became even more widely known as Willie Service Manager at the dealership, and our Roberts decided to provide fried chicken Page 6 - Ads & Info own Jim Moore who was more about while the ladies brought some of the best servicing a few good jokes and playing side dishes and desserts I have ever eaten. -

International Label Discography

International Label Discography: 13000 Series: PR-INT 13001 - Golden Songs of Greece - Spero Spyros [1960] Tsutsurada/Samiotissa/Pounafta Matia/Tria PediaYasu Costa/Egiotissa (Kalamatianos)/Itia (Tsamiko)/Kanarini/Poli Kala/Vlaha/Glendi (Syrtos) PR-INT 13002 - Best of Ed McCurdy - Ed McCurdy [1961] The Miller/Jolly Roger/Chilly Winds/Fireman’s Not For Me/Maidenhead/The Fox/Blues Ain’t Nothing/Doleful Tale/Cindy/Once I Loved a Maiden Fair/Mrs. McGrath/Wee Cooper of Fife/Every Night When the Sun Goes In/John Henry/Ploughman/Old Joe Clark/Lonesome Valley/Good Morrow/Gossip Joan/Branch of May PR-INT 13003 - Best of Jean Ritchie - Jean Ritchie [1961] Shady Grove/Nottamun Town/Old Virginny/I Wonder When I Shall Be Married/Gentle Fair Jenny/Sweet Jane/Pretty Polly/Come All Ye fair and Tender Ladies/Pretty Fair Miss/Goin’ to Boston/Christ Was Born in Bethlehem/Little Devils/Hangman/Children, Go Where I Send thee/Moonshiners/Dying Cowboy/Lord Thomas and Fair Ellender/Lullabies: Go to Sleep Little Baby, Dance to Your Daddy, Go Tell Aunt Rhodie PR-INT 13004 - Best of Ewan MacColl - Ewan MacColl [1961] Cardsong/Shepherd Lad/Gallant Colliers/General Wolfe/Girls Around Cape Horn/Henry Martin/Come All Ye Tramps and Hawkers/Foggy, Foggy Dew/Bonny Ship the Diamond/Cruel Mother/Black Velvet Band/Deserter/Farewell to Tarwathie/Tatties an’ Herrin’ PR-INT 13005 - Best of Peggy Seeger - Peggy Seeger [1961] Pretty Little Baby/Raccoon and Possum/I’ll Not Marry at All/Chickens They are Crowing/Lowlands of Holland/Wagoner’s Lad/Brave Wolfe/Old Woman and Her Little -

America's Roots Music

FREE Volume 1 Number 4 July/August 2001 A BI-MONTHLY NEWSPAPER ABOUT THE HAPPENINGS IN & AROUND THE GREATER LOS ANGELES FOLK COMMUNITY “Don’t you know that Folk Music is illegal in Los Angeles?” –Warren Casey of the Wicked Tinkers AMERICA’S ROOTS MUSIC NEW FILM EXAMINES THE LIFE & MUSIC OF APPALACHIAN PEOPLE ike O Brother, Where Art Thou, singing ballads Songcatcher is a movie where the and young folks plot is built to showcase the fiddling away on music. As with O Brother... the the corner. music being trumpeted is from Songcatcher Appalachia. The haunting songs attempts to give us a glimpse into life in the Songcatcher in the film, as well as on the mountains at the turn of the century. Dr. Lily L soundtrack, represent some of Penleric (JANET MCTEER) is an academic WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY America’s most powerful musical folklorist. When she is passed over again for MAGGIE GREENWALD influences - the roots that later sprout into blue- university promotion, she leaves the universi- WITH JANET MCTEER, EMMY ROSSUM, grass, country music, folk singing, and eventually, the Southern- ty and heads to the mountains where her sister runs a local PAT CARROLL, AIDAN QUINN influenced rock ‘n roll of Elvis Presley. Appalachia remains a schoolhouse. Once there, she “discovers” the treasure-chest hotbed of creative music with new stars such as Iris DeMent ris- of music, sung with such expression and depth that she is at ing out of the old traditions with the rarest of gifts: a high lone- once inspired to tell the world (and make her statement to the some voice and a simple song that can shatter a person’s heart. -

Northern Grass 0715

Summer August Edition 2015 Jerry Schrepfer Editor Summer August Edition Northern Kentucky Bluegrass Music Association 2015 Keeping Bluegrass Music Alive in the Northern Kentucky Area In This Edition “RC Vance, The Fiddle and the Jamboree” Ron Simmons and Jerry Schrepfer When the “Thompson/Chastain/Lovett’ jam Burlington, which now houses the Boone sessions proved to be such a success, it was Co. Water Rescue equipment. The Jamboree rather inevitable that somebody would ramp lasted for 8 years until RC became too ill up the fun and turn it into a real show. That with diabetes to carry on. It takes a strong person was RC Vance. Although I never personality and good management for heard him play a lick, I understand from anything like this to go on that long. It also Page 1 - 5 - Second of many of You whom I spoke to that he was took a lot of good folks who were bent on A Series of articles a man who could “get it done”! having a good time every Friday night. It About the history of seemed at that time the dancers, the Bluegrass jams in It was an era of good Bluegrass Music that performers and the beloved patrons,who just Northern Kentucky was really still considered part of Country loved the music, were a part of the show.It Including photos! Music, so the two genres of music clung to all worked around the lights of the stage and each other on stage and off. It was a time the sound made on a wood dance floor. -

Fiddle-Style Banjo' from the Great Smoky Mountains Ted Olson East Tennessee State University, [email protected]

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University ETSU Faculty Works Faculty Works 2014 Carroll Best: Old-Time 'Fiddle-Style Banjo' from the Great Smoky Mountains Ted Olson East Tennessee State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etsu-works Part of the Appalachian Studies Commons, and the Music Commons Citation Information Olson, Ted. 2014. Carroll Best: Old-Time 'Fiddle-Style Banjo' from the Great Smoky Mountains. The Old-Time Herald. Vol.13(10). 10-19. http://www.oldtimeherald.org/archive/back_issues/volume-13/13-10/best-fv.html ISSN: 1040-3582 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in ETSU Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Carroll Best: Old-Time 'Fiddle-Style Banjo' from the Great Smoky Mountains Copyright Statement © Ted Olson This article is available at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University: https://dc.etsu.edu/etsu-works/1217 CARROLL BEST: OLD-TIME "FIDDLE-STYLE BANJO" FROM THE GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS By Ted Olson Carroll Best and Danny Johnson at the 1992 Tennessee Banjo Institute 10 THE OLD-TIME HERALD WWW.OLDTIMEHERALD.ORG VOLUME 13, N UMBER 10 n an interview published in the February 1992 is sue of The Banjo Newsletter and conducted by blue grass historian Neil Rosenberg and banjo player Iand instruction book author Tony Trischka, Car roll Best conveyed the depth of his connections to the instrument he had mastered: "When I was old enough to pick up a banjo I wanted to play." An affinity for the banjo, he claimed, had been passed down within his family. -

Banjo Greats Gather at Grey Fox for Keith-Style Banjo Summit

The gracious banjo maestro, Bill Keith, shaking hands with Jonny Cody after playing ‘Devil’s Dream’ together at a campsite during Grey Fox 2013—fifty years from the day that Bill first played it with Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys. Photo by Fred Robbins BANJO GREATS GATHER AT GREY FOX FOR KEITH-STYLE BANJO SUMMIT Surely a highlight of this year’s Grey Fox Bluegrass Festival will be a very special Keith-Style Banjo Summit hosted by Béla Fleck and Tony Trischka. As if this “Triple Crown of Banjo” wasn’t enough, joining them on stage to honor the music and enormous influence of Bill Keith will be the award-winning Noam Pikelny, Eric Weissberg, Mike Munford, Marc Horowitz, Mike Kropp, and Ryan Cavanaugh, along with Bill Keith himself. The 90-minute Keith-style banjo gathering will be on Friday, July 17 beginning at 7:00pm at the Creekside Stage. Banjoist extraordinaire Bill Keith (beaconbanjo.com) is one of just a handful of musicians to have a whole style named after him. The Keith style was the catalyst that spawned new generations of envelope pushers such as Tony Trischka, Béla Fleck and Noam Pikelny. Bill has worked with The Jim Kweskin Jugband, Jim Rooney, Red Allen & Frank Wakefield, Judy Collins, Clarence White, Richard Greene and David Grisman. His 1963 Decca recordings with Bill Monroe & The Blue Grass Boys introduced his innovations to a world audience. Bill also wrote the Earl Scruggs banjo instruction book. Last October, the IBMA honored Bill with a richly deserved Distinguished Achievement Award. YOUTUBE LINK: Bill Keith playing Cherokee Shuffle and commenting on the Keith-Style at Grey Fox 2011 in workshop with J.D. -

ACD Calendar.Pdf

Dawg & Artie Rose, 1978 JANUARY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY Milt Jackson b.1923 Roger Miller Jim Buchanan b.1936 1b.1941 2 Al “Jazzbo” Collins Earl Scruggs Kenny Clarke Herbie Nichols b.1919 “Wild Bill” Davidson b.1924 Chano Pozo Elvis Presley b.1914 b.1919 John McLaughlin b.1906 Wyatt Rice b.1915 b.1935 Bucky Pizzarelli 3 4b.1942 5 6b.1965 7 8 9b.1926 Curly Ray Cline Jay McShann b. 1936 Joe Pass Grady Tate b. 1932 Gene Krupa b.1909 Lloyd Loar b.1929 b.1886 b.1923 Rick Shubb Billy Ray Latham b. 1938 Allen Toussaint b. 1938 Alan Lomax b.1925 Max Roach b.1945 Pete Kuykendall Tony Trischka Samson Eli Grisman “T Bone” Burnett b. 1948 Chuck Berry b. 1926 10b.1925 11 12b. 1990 13b.1938 14 15 16b.1949 Charlie Waller Jimmy Cobb Craig Miller Juan Tizol Django Reinhardt Cedar Walton Al Foster b.1935 b.1929 b.1949 b.1900 b.1910 b.1934 b.1944 Dolly Parton Bill Monroe records Tom Rozum Sam Cooke Gary Burton 17 18 19b.1946 “Raw20 Hide” 1951 21b.1951 22b.1935 23b.1943 Joe Albany Clayton McMichen b.1900 Mandolin rumors proven b.1924 Antonio Carlos Jobim Stephane Grappelli b.1908 Wolfgang A. Mozart Mandolins rumored to be false 731 BC Roy Eldridge Carlo Aonzo b.1927 b.1756 to exist 731 BC Ed Shaughnessy b.1911 24b.1962 25 Artie26 Rose b.1931 27 28 29b.1929 30 C.F. Martin 31b.1796 Hal Blaine FEBRUARY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY James P.