1 Puremusic Interview with David Grisman by Frank Goodman (July 2002) a Friend Gave Me a Video Recently, of the Legendary Pr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ross Nickerson-Banjoroadshow

Pinecastle Recording Artist Ross Nickerson Ross’s current release with Pin- ecastle, Blazing the West, was named as “One of the Top Ten CD’s of 2003” by Country Music Television, True West Magazine named it, “Best Bluegrass CD of 2003” and Blazing the West was among the top 15 in ballot voting for the IBMA Instrumental CD of the Year in 2003. Ross Nickerson was selected to perform at the 4th Annual Johnny Keenan Banjo Festival in Ireland this year headlined by Bela Fleck and Earl Scruggs last year. Ross has also appeared with the New Grass Revival, Hot Rize, Riders in the Sky, Del McCoury Band, The Oak Ridge Boys, Nitty Gritty Dirt Band and has also picked and appeared with some of the best banjo players in the world including Earl Scruggs, Bela Fleck, Bill Keith, Tony Trischka, Alan Munde, Doug Dillard, Pete Seeger and Ralph Stanley. Ross is a full time musician and on the road 10 to 15 days a month doing concerts , workshops and expanding his audience. Ross has most recently toured England, Ireland, Germany, Holland, Sweden and visited 31 states and Canada in 2005. Ross is hard at work writing new material for the band and planning a new CD of straight ahead bluegrass. Ross is the author of The Banjo Encyclopedia, just published by Mel Bay Publications in October 2003 which has already sold out it’s first printing. For booking information contact: Bullet Proof Productions 1-866-322-6567 www.rossnickerson.com www.banjoteacher.com [email protected] BLAZING THE WEST ROSS NICKERSON 1. -

Discourses of Decay and Purity in a Globalised Jazz World

1 Chapter Seven Cold Commodities: Discourses of Decay and Purity in a Globalised Jazz World Haftor Medbøe Since gaining prominence in public consciousness as a distinct genre in early 20th Century USA, jazz has become a music of global reach (Atkins, 2003). Coinciding with emerging mass dissemination technologies of the period, jazz spread throughout Europe and beyond via gramophone recordings, radio broadcasts and the Hollywood film industry. America’s involvement in the two World Wars, and the subsequent $13 billion Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe as a unified, and US friendly, trading zone further reinforced the proliferation of the new genre (McGregor, 2016; Paterson et al., 2013). The imposition of US trade and cultural products posed formidable challenges to the European identities, rooted as they were in 18th-Century national romanticism. Commercialised cultural representations of the ‘American dream’ captured the imaginations of Europe’s youth and represented a welcome antidote to post-war austerity. This chapter seeks to problematise the historiography and contemporary representations of jazz in the Nordic region, with particular focus on the production and reception of jazz from Norway. Accepted histories of jazz in Europe point to a period of adulatory imitation of American masters, leading to one of cultural awakening in which jazz was reimagined through a localised lens, and given a ‘national voice’. Evidence of this process of acculturation and reimagining is arguably nowhere more evident than in the canon of what has come to be received as the Nordic tone. In the early 1970s, a group of Norwegian musicians, including saxophonist Jan Garbarek (b.1947), guitarist Terje Rypdal (b.1947), bassist Arild Andersen (b.1945), drummer Jon Christensen (b.1943) and others, abstracted more literal jazz inflected reinterpretations of Scandinavian folk songs by Nordic forebears including pianist Jan Johansson (1931-1968), saxophonist Lars Gullin (1928-1976) bassist Georg Riedel (b.1934) (McEachrane 2014, pp. -

Flatpicking Guitar Magazine Index of Reviews

Flatpicking Guitar Magazine Index of Reviews All reviews of flatpicking CDs, DVDs, Videos, Books, Guitar Gear and Accessories, Guitars, and books that have appeared in Flatpicking Guitar Magazine are shown in this index. CDs (Listed Alphabetically by artists last name - except for European Gypsy Jazz CD reviews, which can all be found in Volume 6, Number 3, starting on page 72): Brandon Adams, Hardest Kind of Memories, Volume 12, Number 3, page 68 Dale Adkins (with Tacoma), Out of the Blue, Volume 1, Number 2, page 59 Dale Adkins (with Front Line), Mansions of Kings, Volume 7, Number 2, page 80 Steve Alexander, Acoustic Flatpick Guitar, Volume 12, Number 4, page 69 Travis Alltop, Two Different Worlds, Volume 3, Number 2, page 61 Matthew Arcara, Matthew Arcara, Volume 7, Number 2, page 74 Jef Autry, Bluegrass ‘98, Volume 2, Number 6, page 63 Jeff Autry, Foothills, Volume 3, Number 4, page 65 Butch Baldassari, New Classics for Bluegrass Mandolin, Volume 3, Number 3, page 67 William Bay: Acoustic Guitar Portraits, Volume 15, Number 6, page 65 Richard Bennett, Walking Down the Line, Volume 2, Number 2, page 58 Richard Bennett, A Long Lonesome Time, Volume 3, Number 2, page 64 Richard Bennett (with Auldridge and Gaudreau), This Old Town, Volume 4, Number 4, page 70 Richard Bennett (with Auldridge and Gaudreau), Blue Lonesome Wind, Volume 5, Number 6, page 75 Gonzalo Bergara, Portena Soledad, Volume 13, Number 2, page 67 Greg Blake with Jeff Scroggins & Colorado, Volume 17, Number 2, page 58 Norman Blake (with Tut Taylor), Flatpickin’ in the -

Solo Concert with Bjarke Falgren

Solo Concert with Bjarke Falgren The prize-winning and 4 times Grammy Award winner Bjarke Falgren and his 300 years old violin invite you on a musical journey with personal and passionate stories added all the big emotions that music has to offer. Bjarke Falgren’s own music finds its inspiration from “a world of music” with Folk music, Jazz, and Classical music as its center of rotation. Improvisation and “creation in the moment” are central elements in the solo concerts, and Bjarke uses - amongst other things - a loop pedal to create his strongly personal sound universe. Many highlight Bjarke as a fiddler who masters his instrument to a degree that caused Svend Asmussen himself, before passing away, to declare that Bjarke should be the first one to receive “The Ellen & Svend Asmussen Prize 2017”. Reviews of Bjarke´s Solo Concerts: “As an organizer, your expectations are always exceeded when booking Bjarke Falgren. More warmth, more dialogue, more humor, more energy, more play. And then this huge and heartfelt joy of being a musician and a mediator of a trade which, with Bjarke Falgren’s talent, reaches far beyond the title of ‘an artist’”. - Sofie Rask Andersen, Dramaturge KGL+, The Royal Theatre, Denmark “Bjarke Falgren has visited Den Rytmiske Højskole (The Rhythmical folk high school) on several occasions. Besides a musical approach on an equilibristic level, Bjarke Falgren creates with his music and storytelling a unique atmosphere, which touches and embraces all listeners. A very special solo concert. “ Stig Kaufmanas, musician and folk high school teacher at Den Rytmiske Højskole “It was a beautiful musical experience. -

Sunday.Sept.06.Overnight 261 Songs, 14.2 Hours, 1.62 GB

Page 1 of 8 ...sunday.Sept.06.Overnight 261 songs, 14.2 hours, 1.62 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Go Now! 3:15 The Magnificent Moodies The Moody Blues 2 Waiting To Derail 3:55 Strangers Almanac Whiskeytown 3 Copperhead Road 4:34 Shut Up And Die Like An Aviator Steve Earle And The Dukes 4 Crazy To Love You 3:06 Old Ideas Leonard Cohen 5 Willow Bend-Julie 0:23 6 Donations 3 w/id Julie 0:24 KSZN Broadcast Clips Julie 7 Wheels Of Love 2:44 Anthology Emmylou Harris 8 California Sunset 2:57 Old Ways Neil Young 9 Soul of Man 4:30 Ready for Confetti Robert Earl Keen 10 Speaking In Tongues 4:34 Slant 6 Mind Greg Brown 11 Soap Making-Julie 0:23 12 Volunteer 1 w/ID- Tony 1:20 KSZN Broadcast Clips 13 Quittin' Time 3:55 State Of The Heart Mary Chapin Carpenter 14 Thank You 2:51 Bonnie Raitt Bonnie Raitt 15 Bootleg 3:02 Bayou Country (Limited Edition) Creedence Clearwater Revival 16 Man In Need 3:36 Shoot Out the Lights Richard & Linda Thompson 17 Semicolon Project-Frenaudo 0:44 18 Let Him Fly 3:08 Fly Dixie Chicks 19 A River for Him 5:07 Bluebird Emmylou Harris 20 Desperadoes Waiting For A Train 4:19 Other Voices, Too (A Trip Back To… Nanci Griffith 21 uw niles radio long w legal id 0:32 KSZN Broadcast Clips 22 Cold, Cold Heart 5:09 Timeless: Hank Williams Tribute Lucinda Williams 23 Why Do You Have to Torture Me? 2:37 Swingin' West Big Sandy & His Fly-Rite Boys 24 Madmax 3:32 Acoustic Swing David Grisman 25 Grand Canyon Trust-Terry 0:38 26 Volunteer 2 Julie 0:48 KSZN Broadcast Clips Julie 27 Happiness 3:55 So Long So Wrong Alison Krauss & Union Station -

Jack Pearson

$6.00 Magazine Volume 16, Number 2 January/February 2012 Jack Pearson Al Smith Nick DiSebastian Schenk Guitars 1 Flatpicking Guitar Magazine January/February 2012 design by [email protected] by “I am very picky about the strings I use on my Kendrick Custom Guitar, and GHS gives me unbeatable tone in a very long lasting string.” GHS Corporation / 2813 Wilber Avenue / Battle Creek . Michigan 49015 / 800 388 4447 2 Flatpicking Guitar Magazine January/February 2012 Block off February 23 thru the 26th!! Get directions to the Hyatt Regency in Bellevue, WA. Make hotel & travel arrangements. Purchase tickets for shows and workshops! Practice Jamming!! Get new strings! Bookmark wintergrass.com for more information! Tell my friends about who’s performing: Ricky Skaggs & Kentucky Thunder Tim O’Brien, The Wilders, The Grascals, The Hillbenders, Anderson Family Bluegrass and more!!! Practice Jamming!!!!! wintergrass.com 3 Flatpicking Guitar Magazine January/February 2012 Feb 23-26th 4 Flatpicking Guitar Magazine January/February 2012 1 Flatpicking Guitar Magazine January/February 2012 CONTENTS Flatpicking FEATURES Jack Pearson & “Blackberry Pickin’” 6 Guitar Schenk Guitars 25 Flatpick Profile: Al Smith & “Take This Hammer” 30 Magazine CD Highlight: Nick DiSebastian: “Snowday” 58 The Nashville Number System: Part 2 63 Volume 16, Number 2 COLUMNS January/February 2012 Bluegrass Rhythm Guitar: Homer Haynes 15 Published bi-monthly by: Joe Carr High View Publications Beginner’s Page: “I Saw the Light” 18 P.O. Box 2160 Dan Huckabee Pulaski, VA 24301 -

Number 108 • Summer 2005 2005 Conference Breaks All Records! Events Our Recent Annual Conference in Austin Was a Great Success, and Just a Whole Lot of Fun

Newsletter Association For Recorded Sound Collections Number 108 • Summer 2005 2005 Conference Breaks All Records! Events Our recent annual conference in Austin was a great success, and just a whole lot of fun. The weather was magnificent, the banquet outstanding, the March 17-20, 2006. 40th Annual ARSC Conference, Seattle, Washington. http:// fellowship stimulating, and the presentations were interesting and varied. www.arsc-audio.org/ Official attendance for the Austin conference was 175, which bested our previous record by around 50 persons, and we had 75 first-timers, many August 13-14, 2005. CAPS Show and Sale, of whom indicated that they would be attending future conferences. Buena Park, CA. http://www.ca-phono.org/ show_and_sale.html Thanks to our Lo- cal Arrangements August 15-21, 2005. Society of American Committee, tours Archivists (SAA), Annual Meeting, New to the Lyndon B. Orleans, LA. http://www.archivists.org/ Johnson Presiden- conference/index.asp tial Library and the Austin City September 11-15, 2005. International Asso- Limits studio went ciation of Sound and Audiovisual Ar- chives (IASA), Annual Conference, Barcelona, without a hitch, Spain. Archives speak: who listens? http:// and other than a www.gencat.net/bc/iasa2005/index.htm brief Texas frog- strangler, the October 7-10, 2005. Audio Engineering Soci- weather was ety (AES), Annual Convention, New York City. beautiful and http://www.aes.org/events/119/ David Hough, audio engineer for the PBS program Austin City Lim- cooperative. its, on the set of the show at the KLRU studios on the UT campus. October 23, 2005. Mechanical Music We had nearly 100 Extravaganza. -

Acoustic Guitar Songs by Title 11Th Street Waltz Sean Mcgowan Sean

Acoustic Guitar Songs by Title Title Creator(s) Arranger Performer Month Year 101 South Peter Finger Peter Finger Mar 2000 11th Street Waltz Sean McGowan Sean McGowan Aug 2012 1952 Vincent Black Lightning Richard Thompson Richard Thompson Nov/Dec 1993 39 Brian May Queen May 2015 50 Ways to Leave Your Lover Paul Simon Paul Simon Jan 2019 500 Miles Traditional Mar/Apr 1992 5927 California Street Teja Gerken Jan 2013 A Blacksmith Courted Me Traditional Martin Simpson Martin Simpson May 2004 A Daughter in Denver Tom Paxton Tom Paxton Aug 2017 A Day at the Races Preston Reed Preston Reed Jul/Aug 1992 A Grandmother's Wish Keola Beamer, Auntie Alice Namakelua Keola Beamer Sep 2001 A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall Bob Dylan Bob Dylan Dec 2000 A Little Love, A Little Kiss Adrian Ross, Lao Silesu Eddie Lang Apr 2018 A Natural Man Jack Williams Jack Williams Mar 2017 A Night in Frontenac Beppe Gambetta Beppe Gambetta Jun 2004 A Tribute to Peador O'Donnell Donal Lunny Jerry Douglas Sep 1998 A Whiter Shade of Pale Keith Reed, Gary Brooker Martin Tallstrom Procul Harum Jun 2011 About a Girl Kurt Cobain Nirvana Nov 2009 Act Naturally Vonie Morrison, Johnny Russel The Beatles Nov 2011 Addison's Walk (excerpts) Phil Keaggy Phil Keaggy May/Jun 1992 Adelita Francisco Tarrega Sep 2018 Africa David Paich, Jeff Porcaro Andy McKee Andy McKee Nov 2009 After the Rain Chuck Prophet, Kurt Lipschutz Chuck Prophet Sep 2003 After You've Gone Henry Creamer, Turner Layton Sep 2005 Ain't It Enough Ketch Secor, Willie Watson Old Crow Medicine Show Jan 2013 Ain't Life a Brook -

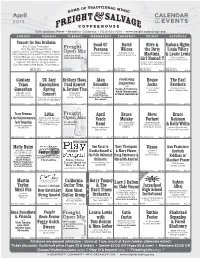

April CALENDAR of EVENTS

April CALENDAR 2013 OF EVENTS 2020 Addison Street • Berkeley, California • (510) 644-2020 • www.freightandsalvage.org SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY Concert for Sue Draheim eric & Suzy Thompson, Good Ol’ David Olive & Barbara Higbie, Jody Stecher & kate brislin, Freight laurie lewis & Tom rozum, kathy kallick, Persons Wilcox the Dirty Linda Tillery Open Mic California bluegrass the best of pop Gerry Tenney & the Hard Times orchestra, pay your dues, trailblazers’ reunion and folk aesthetics Martinis, & Laurie Lewis Golden bough, live oak Ceili band with play and shmooze Hills to Hollers the Patricia kennelly irish step dancers, Girl Named T album release show Tempest, Will Spires, Johnny Harper, rock ‘n’ roots fundraiser don burnham & the bolos, Tony marcus for the rex Foundation $28.50 adv/ $4.50 adv/ $20.50 adv/ $24.50 adv/ $20.50 adv/ $22.50 adv/ $30.50 door monday, April 1 $6.50 door Apr 2 $22.50 door Apr 3 $26.50 door Apr 4 $22.50 door Apr 5 $24.50 door Apr 6 Gautam UC Jazz Brittany Haas, Alan Celebrating House The Earl Songwriters Tejas Ensembles Paul Kowert Senauke with Jacks Brothers Zen folk musician, Caren Armstrong, “the rock band Outlaw Hillbilly Ganeshan Spring & Jordan Tice featuring Keith Greeninger without album release show Carnatic music string fever Jon Sholle, instruments” with distinction Concert from three Chad Manning, & Steve Meckfessel and inimitable style featuring the Advanced young virtuosos Suzy & Eric Thompson, Combos and big band Kate Brislin $20.50/$22.50 Apr 7 $14.50/$16.50 Apr -

Jim-Rooney-Daa-Induction-By-Menius

Jim Rooney DAA Presentation by Art Menius IBMA World of Bluegrass Awards Luncheon September 29, 2016 Jim Rooney did me a big favor, writing. In It for the Long Run: A Musical Memoir, so that I could do this presentation. That’s being a friend. Jim is a man who has done it all while enjoying being in it for the long run in many relationships. Think of Bill Keith, Eric von Schmidt, or his eventual spouse Carol Langstaff. At Owensboro I remember Jim, tall and commanding, as his left hand powered the rhythm on a kick ass rendition of Six White Horses.” Not that he limited himself to Monroe covers. His interpretation of the Stones’ “No Expectations” became a go to song. His love for bluegrass began back in Massachusetts in the 1950s when he heard on a band called the Confederate Mountaineers at radio station WCOP. Inspired by the Lillys, Tex, and Stovepipe, it wasn’t too long before Jim was on WCOP himself and hooked on performing. At Amherst he met Bill Keith who would be a friend and musical partner for much of the next 60 years. In 1962, they recorded “Devils Dream” and “Sailor’s Hornpipe,” the first documentation of Bill’s chromatic style shortly before he joined the Blue Grass Boys. The tracks appeared on their Living on the Mountain LP. Their many collaborations would include the revolutionary Blue Velvet Band whose music spread worldwide person to person Mud Acres, and concerts and tours with many different aggregations and combinations. Jim enjoyed sharing a heritage award from the Boston Bluegrass Union and brought us to tears at Bill’s induction into the Hall of Fame. -

David Grisman Quintet to Play University Theatre

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present University Relations 6-7-2001 David Grisman Quintet to play University Theatre University of Montana--Missoula. Office of University Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/newsreleases Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation University of Montana--Missoula. Office of University Relations, "David Grisman Quintet to play University Theatre" (2001). University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present. 17322. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/newsreleases/17322 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Relations at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Montana UNIVERSITY RELATIONS • MISSOULA, MT 59812 • 406-243-2522 • FAX: 406-243-4520 This release is available electronically on INN (News Net.) or the News Release Web site at www.umt.edu/urelations/releases/. June 7, 2001 Contact: Tom Webster, director, University Theatre Productions, (406) 243-2853. DAVID GRISMAN QUINTET TO PLAY UNIVERSITY THEATRE MISSOULA-- The man called “Dawg” will bring his unique blend of acoustic sounds to Missoula for a September concert. The David Grisman Quintet will perform at 8 p.m. Tuesday, Sept. 4, in the University Theatre. Tickets are $21 in advance or $23 the day of the show. They are on sale now at all Tic-It-E-Z outlets or by calling (888) MONTANA or 243-4051 in Missoula. -

Download Booklet

120762bk DorseyBros 14/2/05 8:43 PM Page 8 The Naxos Historical labels aim to make available the greatest recordings of the history of recorded music, in the best and truest sound that contemporary technology can provide. To achieve this aim, Naxos has engaged a number of respected restorers who have the dedication, skill and experience to produce restorations that have set new standards in the field of historical recordings. Available in the Naxos Jazz Legends and Nostalgia series … 8.120625* 8.120628 8.120632* 8.120681* 8.120697* 8.120746* * Not available in the USA NAXOS RADIO Over 70 Channels of Classical Music • Jazz, Folk/World, Nostalgia www.naxosradio.com Accessible Anywhere, Anytime • Near-CD Quality 120762bk DorseyBros 14/2/05 8:43 PM Page 2 THE DORSEY BROTHERS Personnel Tracks 1, 3 & 4: Bunny Berigan, trumpet; Tracks 8-11: Manny Klein & unknown, trumpet; ‘Stop, Look and Listen’ Original 1932-1935 Recordings Tommy Dorsey, trombone; Jimmy Dorsey, Tommy Dorsey, Glenn Miller, trombones; clarinet, alto sax; Larry Binyon, tenor sax; Jimmy Dorsey, clarinet, alto sax; unknown, alto Whether you call them The Fabulous or The over to the newly formed American Decca label. Fulton McGrath, piano; Dick McDonough, sax; Larry Binyon (?), tenor sax; Fulton Battling Dorsey Brothers, Tommy (1905-1956) In the two knock-down drag-out years that guitar; Artie Bernstein, bass; Stan King, drums McGrath (?), piano; Dick McDonough, guitar; and Jimmy Dorsey (1904-1957) were major followed, the Dorseys produced some Track 2: Bunny Berigan, trumpet; Tommy Artie Bernstein (?), bass; Stan King or Ray influences on the development of jazz in the outstanding and exciting jazz, all the while Dorsey, trombone; Jimmy Dorsey, clarinet; McKinley, drums 1920s and ’30s.