Using Ethnography to Investigate the Intersections of Race and Resilience in the Case of the National Flood Insurance Program in Canarsie, Brooklyn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cohort 20 Graduation Celebration Ceremony February 7, 2020

COHORT 20 GRADUATION CELEBRATION CEREMONY FEBRUARY 7, 2020 Green City Force is an AmeriCorps program CONGRATULATIONS TO THE GRADUATES OF COHORT 20! WELCOME! Welcome to the graduation celebration for Green City Force’s (GCF) 20th Cohort! Green City Force’s AmeriCorps program prepares young adults, aged 18-24, who reside at NYCHA and have a high school diploma or equivalency for careers through green service. Being part of the Service Corps is a full-time commitment encompass- ing service, training, and skills-building experiences related to sustainable buildings and communities. GCF is committed to the ongoing success of our alumni, who num- ber nearly 550 with today’s graduates. The Corps Members of Cohort 20 represent a set of diverse experiences, hailing from 20 NYCHA developments and five boroughs. This cohort was the largest cohort as- signed to Farms at NYCHA, totaling 50 members for 8 and 6 months terms of service. The Cohort exemplifies our one corps sustainable cities service in response to climate resilience and community cohesion through environmental stewardship, building green infrastructure and urban farming, and resident education at NYCHA. We have a holistic approach to sustainability and pride ourselves in training our corps in a vari- ety of sectors, from composting techniques and energy efficiency to behavior change outreach. Cohort 20 are exemplary leaders of sustainability and have demonstrated they can confidently use the skills they learn to make real contributions to our City. Cohort 20’s service inspired hundreds of more residents this season to be active in their developments and have set a new standard for service that we are proud to have their successors learn from and exceed for even greater impact. -

Farms at NYCHA

Farms at NYCHA Final Evaluation Report June, 2019 1 Acknowledgements This evaluation was made possible through the generous support of the New York Community Trust and Laurie M. Tisch Illumination Fund. Special thanks to the staff at partner organizations, NYCHA residents, and Green City Force Corps Members who supported this evaluation by participating in and facilitating interviews, focus groups, surveys, and site visits. Farms at NYCHA Initiative Kristine Momanyi, and Hannah Altman- NYC Office of the Mayor Kurosaki. Darren Bloch, Senior Advisor to the Mayor Tamara Greenfield, Director of Building Healthy Communities Project Partners Resident Associations New York City Housing Authority Cheryl Boyce, Resident Leader, Bayview Andrea Mata, Director for Community Houses Health Initiatives Naomi Johnson, Resident Leader, Howard Regina Ginyard, Urban Farm Project Houses Coordinator Frances Brown, Resident Leader, Red Hook East Mayor’s Fund to Advance New York City Lillie Marshall, Resident Leader, Red Hook Toya Williford, Executive Director West Leah Prestamo, Director of Programs and Katie Harris, Tenant Association President, Policy Wagner Houses Janet Seabrook, Acting Tenant Association Fund for Public Health NYC President, Wagner Houses Sara Gardner, Executive Director Brenda Kiko Charles, Tenant Association Donna Fishman, Deputy Director President. Mariner’s Harbor Houses Erik Farmer, Tenant Association President, Green City Force Forest Houses Lisbeth Shepherd, Chief Executive Officer Tonya Gayle, Chief Development Officer Community -

Vending Machines for NYCHA

First-Class U.S. Postage Paid New York, NY Permit No. 4119 Vol. 38, No. 3 www.nyc.gov/nycha MARCH 2008 NYCHA ADOPTS PRELIMINARY BUDGET FOR 2008 By Eileen Elliott THE NEW YORK CITY HOUSING of New York City and while we contribute to the deficit include: AUTHORITY (NYCHA) BOARD do have to make tough choices, the cost of operating 21 State and ADOPTED A $2.8 BILLION we have nearly 70 years of being City-built developments, which FISCAL YEAR 2008 PRELIMI- the first, the biggest and the best. amounts to $93 million annually; NARY OPERATING BUDGET We’ll get through this. We’ve an increase in non-discretionary ON JANUARY 23rd. The budget been through hard times before.” employee benefit expenses of $40 includes a $195 million structural million; $68 million for policing deficit, resulting in large part Chronic Federal services; and another $68 million from chronic Federal under- Underfunding for NYCHA-provided community funding. Before adopting the “NYCHA has lost over $611 and social services. budget, NYCHA Chairman Tino million in Federal aid since Hernandez vowed that the 2001,” said NYCHA Deputy Victories Housing Authority will continue General Manager for Finance “In many ways, NYCHA is to take aggressive action in the Felix Lam in his budget presenta- a victim of its own success,” coming year to preserve public tion at the meeting. He added that said Chairman Tino Hernandez, housing in New York City. the last time public housing was referring to the fact that NYCHA fully funded was in 2002. has managed to maintain its level Commitment to For 2008, the Federal subsidy of service despite nearly seven DISINVESTMENT The graph above shows the decline in Public Housing NYCHA receives will again be years of underfunding. -

Download The

ASSEMBLY MEMBER Reports to the People Fall 2017 5318 Avenue N, 1st Floor, Brooklyn, NY 11234 • 718-252-2124 Room 523 LOB, Albany, New York 12248 • 518-455-5211 • [email protected] ASSEMBLY MEMBER’S MESSAGE It was just a short five years ago that Super Storm Sandy de- stroyed so much of our district. The five year anniversary of Super Storm Sandy has just occurred and in light of the recent hurricane that plagued the Caribbean, I believe we should take note of how we helped one another during Sandy. At that time I was work- ing as a social worker for Catholic Charities and I witnessed the residents of Canarsie, Coney Island and Far Rockaway trying to resume their lives. The lessons of Super Storm Sandy will remain, and we are always going to be looked to for assistance in helping overcome tragedies as this is a cornerstone of our great 59th As- sembly District. RECENT LEGISLATION Assembly passes extender of ticket resale law – protecting the consumers and residents of New York “On the turn of a dime the technology utilized to sell tickets practice. Bill A7701 allows accommodating for the market as it for entertainment venues changes, without proper safety protocols evolves; ensuring the protection of consumers and their rights. in place the average consumer becomes a target and a victim, a This legislation allows for additional time to fully understand the practice I will not allow on my watch,” remarked Assembly Mem- effects that new technologies and other developments, with respect ber Williams. Assembly Member Williams brought to fruition to ticket sales, will have on the industry and consumers alike. -

Nourishing NYCHA: Food Policy As a Tool for Improving the Well-Being of New York City’S Public Housing Residents February 2017

Nourishing NYCHA: Food Policy as a Tool for Improving the Well-Being of New York City’s Public Housing Residents February 2017 By Nevin Cohen, Nick Freudenberg, and Craig Willingham, CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute In the last few years, NYCHA has attracted the attention of policy makers, developers, elected officials and activists seeking new ways to improve living conditions, enhance public safety, repair an aging infrastructure, encourage economic development and promote health in the city-within-a-city that New York’s public housing constitutes. In this policy brief, we consider another aspect of NYCHA: the food its residents buy, prepare and eat and the role food plays in the health, environment and economy of the city’s NYCHA population. Our goal is to contribute new insights into how NYCHA can use food policy and programs to improve the well-being of its residents and make our city healthier, more self-sufficient, safer and more sustainable. More specifically, we hope to identify what NYCHA is doing now and what it 1-Credit: NYU-CUNY Prevention Research Center, Reference 4 55 West 125th Street, 6th Floor New York, NY 10027 (646) 364-9602 [email protected] www.cunyurbanfoodpolicy.org 1 could be doing in the coming years to reduce food insecurity, diet-related health conditions and promote food-related economic development, employment and sustainability. Why Food at NYCHA? The starting point of any investigation of NYCHA properly begins with the people who live there. What is known about the health status of NYCHA’s public housing community? Health and Diet in NYCHA Residents High death rates from diet-related chronic diseases. -

![The Commoditization of Starbucks[Electronic Version]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6093/the-commoditization-of-starbucks-electronic-version-2216093.webp)

The Commoditization of Starbucks[Electronic Version]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by School of Hotel Administration, Cornell University Cornell University School of Hotel Administration The Scholarly Commons Articles and Chapters School of Hotel Administration Collection 2010 The ommoC ditization of Starbucks Cathy A. Enz Cornell University School of Hotel Administration, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.sha.cornell.edu/articles Part of the Food and Beverage Management Commons Recommended Citation Enz, C. A. (2010). The commoditization of Starbucks[Electronic version]. Retrieved [insert date] from Cornell University, School of Hotel Administration site: http://scholarship.sha.cornell.edu/articles/609 This Article or Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Hotel Administration Collection at The choS larly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles and Chapters by an authorized administrator of The choS larly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The ommoC ditization of Starbucks Abstract [Excerpt] Is the coffee empire that Starbucks built beginning to fall? In a memo sent to the senior management of the company in February 2007, Howard Schultz warned that Starbucks was in danger of losing its romance and theater, which he believes are fundamental to the Starbucks experience. He noted, “Over the past ten years in order to achieve the growth, development, and scale necessary to go from less than 1,000 stores to 13,000 stores and beyond, we have had to make a series of decisions that, in retrospect, have led to the watering down of the Starbucks experience, and, what some might call the commoditization of our brand.” Calling the memo subject “The ommodC itization of the Starbucks Experience,” Schultz questioned corporate decisions to use automatic espresso machines and eliminate some in-store coffee grinding. -

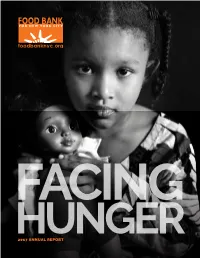

2017 Annual Report

RE: Edits for Annual Report FACING HUNGER2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 ANNUAL REPORT | FOOD BANK FOR NEW YORK CITY A 2017 BOARD OF DIRECTORS REVEREND HENRY BELIN (Chair) KATIE LEE MICHAEL SMITH PASTOR CHEF/AUTHOR GENERAL MANAGER Bethel AME Church The Comfort Table Cooking Channel MARIO BATALI SERAINA MACIA ARTHUR STAINMAN (Treasurer) CHEF/AUTHOR/RESTAURATEUR EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT & CEO SENIOR MANAGING DIRECTOR First Manhattan KEVIN FRISZ AIG MANAGING PARTNER GLORIA PITAGORSKY (Vice Chair) LARY STROMFELD William James Capital MANAGING DIRECTOR (Executive Vice Chair) Heard City PARTNER JOHN F. FRITTS, ESQ. (Secretary) Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft LLP SENIOR COUNSEL NICOLAS POITEVIN Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft LLP SENIOR TRADER STANLEY TUCCI Latour Trading ACTOR/DIRECTOR LAUREN BUSH LAUREN Olive Productions C/O Post Factory CEO & FOUNDER LEE SCHRAGER FEED VICE PRESIDENT, CORPORATE PASTOR MICHAEL WALROND COMMUNICATIONS & NATIONAL EVENTS SENIOR PASTOR Southern Glazer’s Wine & Spirits First Corinthian Baptist Church Kelly Bensimon Tony Shaloub David Chang Kate Krader AGENCY ACTOR, MODEL ACTOR CHEF, AUTHOR BLOOMBERG ADVISORY Lorraine Bracco Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson Caryl Chinn Gabriel Kreuther COMMITTEE ACTOR MUSICIAN, RESTAURATEUR, CARYL CHINN CULINARY CHEF, RESTAURATEUR AUTHOR CONSULTING Robin Sirota-Bassin Ty Burrell Emeril Lagasse Tom Colicchio SOUTHSIDE UNITED HDFC INC. ACTOR CHEF, TV HOST, AUTHOR CHEF, TV HOST, AUTHOR Cheryl Cancela Helena Christensen CULINARY Katie Lee Gabriele Corcos THE SALVATION ARMY STAPLETON MODEL, PHOTOGRAPHER -

Table of Contents

Southern Brooklyn Transportation Investment Study Kings County, New York P.I.N. X804.00; D007406 Technical Memorandum #2 Existing Conditions DRAFT June 2003 Submitted to: New York Metropolitan Transportation Council Submitted by: Parsons Brinckerhoff In association with: Cambridge Systematics, Inc. SIMCO Engineering, P.C. Urbitran Associates, Inc. Zetlin Strategic Communications TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..................................................................................................... ES-1 A. TRANSIT SYSTEM USAGE AND OPERATION.................................................................. ES-1 B. GOODS MOVEMENT...................................................................................................... ES-2 C. SOCIOECONOMIC CONDITIONS ..................................................................................... ES-4 D. ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS .................................................................................... ES-5 E. ACCIDENTS AND SAFETY.............................................................................................. ES-5 F. PEDESTRIAN/BICYCLE TRANSPORTATION.................................................................... ES-6 CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................I-1 A. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................I-1 B. PROJECT OVERVIEW..........................................................................................................I-1 -

July 2016 Inside This Issue 3 4 5

VOL. 46 NO. 5 JULY 2016 INSIDE THIS ISSUE 3 4 5 Randolph Mayor Talks Houses When Smaller Safety Makeover Is Better Joseph Kemp: The Voice of Youth on Public Safety Playing with PALs NYCHA’S NEWLY FORMED Public Safety Advisory A new court Committee, which brings together residents and management with the NYPD and other commu- at Frederick nity partners to make communities safer, held its first meeting in June. At the table was 21-year-old Samuel Joseph Kemp, appointed to the committee after a citywide search for a NYCHA resident to represent Houses will public housing tenants. A resident of Queensbridge Houses since the age of 6, this aspiring attorney see plenty is passionate about making NYCHA communities of action safer for everyone. “I joined the Public Safety Advisory Committee this summer because I see the issues that occur in my neighbor- hood, and I want to be able to make an impact in T WAS CLOSE, but the correcting them,” Mr. Kemp explains. “I want to Kids beat the Cops. On make our communities safer, for both residents and I June 7, youth from the visitors. Every community has its issues, problems Frederick E. Samuel Com- that can be fixed, and with this opportunity, I can munity Center’s basketball help solve some of those problems.” team beat NYPD officers He seeks to bring a young person’s perspective to 62-52 at the first basketball the committee’s work, believing that “Education for game held in the center’s youth is a key way to promote public safety. -

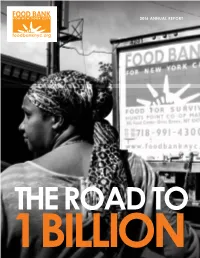

2016 Annual Report

2016 ANNUAL REPORT THE ROAD TO 1 BILLION 2016 BOARD AGENCY Ty Burrell Ken Biberaj Hung Huynh OF DIRECTORS ADVISORY ACTOR RESTAURATEUR CHEF COMMITTEE Helena Christensen April Bloomfield Dan Kluger MODEL, PHOTOGRAPHER CHEF CHEF Mario Batali Robin Sirota Bassin CHEF/AUTHOR/RESTAURATEUR SOUTHSIDE UNITED HDFC Alan Cumming Danny Bowien Kate Krader INC./LOS SURES SOCIAL ACTOR CHEF, RESTAURATEUR FOOD & WINE MAGAZINE Reverend Henry Belin SERVICES (Chair) Lisa Boyd Gavin DeGraw Daniel Boulud Emeril Lagasse MUSICIAN CHEF, AUTHOR CHEF, TV HOST, AUTHOR PASTOR NORTHEAST BROOKLYN BETHEL AME CHURCH HOUSING DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION Selita Ebanks Anthony Bourdain Katie Lee Kevin Frisz MODEL CHEF, TV HOST, AUTHOR TV HOST MANAGING PARTNER Sara Cohen WILLIAM JAMES CAPITAL JEWISH COMMUNITY CENTER Dominic Fumusa Tim Buma Jennifer Leuzzi OF STATEN ISLAND ACTOR CHEF ADVERTISING, MARKETING & EDITORIAL CONSULTANT John F. Fritts, Esq. Allison Deal Cat Greenleaf David Burke (Secretary) METROPOLITAN COUNCIL ON HOST, NBC NEW YORK CHEF, AUTHOR Michael Lomonaco SENIOR COUNSEL JEWISH POVERTY CHEF, AUTHOR CADWALADER, WICKERSHAM & TAFT LLP Ethan Hawke Anne Burrell ONE WORLD FINANCIAL CENTER Pe’er Deutsch ACTOR CHEF, TV HOST, AUTHOR Marisa May ONEG SHABBOS SD26 EVENTS Lauren Bush Lauren Michael Kay Andrew Carmellini CEO & FOUNDER Maria Estrada SPORTS BROADCASTER CHEF, AUTHOR Masaharu Morimoto FEED EVERY DAY IS A MIRACLE CHEF, AUTHOR Lenny Kravitz Cesare Casella Katie Lee Rev. Vincent Fusco MUSICIAN CHEF, AUTHOR Seamus Mullen THE COMFORT TABLE ACTS COMMUNITY CHEF, AUTHOR, -

MASTER PFRED DIRECTORY by BOROUGH.Xlsx

MASTER PFRED DIRECTORY BY BOROUGH Name EFAP provider? Address City State Zip code Organization Phone Number MANHATTAN ADVENT LUTHERAN CHURCH - PANTRY Yes 2504 BROADWAY NEW YORK NY 10025 212-665-2504 ADVENT LUTHERAN CHURCH - SOUP KITCHEN Yes 2504 BROADWAY NEW YORK NY 10025 212-665-2504 ANTIOCH OUTREACH MINISTRIES Yes 41 WEST 124TH STREET NEW YORK NY 10027 212-534-5715 CONGREGATION B'NAI JESHURUN Yes 257 WEST 88TH STREET NEW YORK NY 10024 2127877600 Holy Apostles Soup Kitchen Yes 296 9th Ave NEW YORK NY 10001 2129240167 LITTLE SISTERS OF THE ASSUMPTION FAMILY HEALTH SERVICE Yes 333 EAST 115TH STREET NEW YORK NY 10029 646-672-5200 MT. OLIVET BAPTIST CHURCH COMMUNITY MEAL PROGRAM Yes 201 LENOX AVE NEW YORK NY 10027 2128641155 NATIONAL COUNCIL OF JEWISH WOMEN Yes 241 WEST 72ND STREET NEW YORK NY 10023 2127997205 NAZARETH HOUSING INC Yes 206 EAST 4TH STREET NEW YORK NY 10009 212-477-7017 NEW YORK CITY LOVE KITCHEN INC Yes 3816 9TH AVE NEW YORK NY 10034 2129424204 PROJECT CREATE - ANTHONY HOUSE Yes 73 LENOX AVE NEW YORK NY 10026 212-663-1596 RAUSCHENBUSCH METRO MINISTRIES INC. Yes 410 WEST 40TH STREET NEW YORK NY 10018 2125944464 SALEM UNITED METHODIST CHURCH Yes 2190 ADAM CLAYTON POWELL JR BLVD NEW YORK NY 10027 212-678-2700 Salvation Army Manhattan Citadel Yes 175 East 125th Street NEW YORK NY 10035 2128603200 THE FATHER'S HEART MINISTRIES Yes 543-545 EAST 11TH STREET NEW YORK NY 10009 212-375-1765 VISION URBANA Yes 66 ESSEX STREET NEW YORK NY 10002 646-626-9748 WESTSIDE CAMPAIGN AGAINST HUNGER Yes 263 W. -

April 2017 Inside This Issue 4 6 11

VOL. 47 NO. 3 APRIL 2017 INSIDE THIS ISSUE 4 6 11 One-Stop Human Rights Ready for the Kiosk Hero Limelight NYCHA CHAIR ANNOUNCES NEW PARTNERSHIP TO PRESERVE PUBLIC HOUSING On March 27, Chair & CEO Shola Olatoye Farm in a Box addressed more than 900 affordable housing leaders at the National Association of Housing and Redevelopment (NAHRO) annual meeting in Washington. She announced that NYCHA and NAHRO have banded together to build a national movement of Public Housing Authorities (PHAs) and their advocates and partners. The coalition will lobby at the local, state and national levels for increased investment in public housing as a critical public health measure. Here is an excerpt of her address. I’ll be honest, when the President proposes a $6.2 billion cut to HUD’s budget and a reported two-thirds slash to the capital fund — you have to wonder if public housing will even have a tomorrow, let alone a “better” one. Luckily, where I’m from, we don’t take these kinds of threats lying down. Public housing authorities and housing administrators have embraced private investment not as a last resort but as a bridge to a 21st century business model. As public housing is faced with a fundamental shift in funding, programs like RAD (the (CONTINUED ON PAGE 14) A NYCHA resident and Green City Force graduate launches farm inside a shipping container. Lexington Houses resident Paul Philpott at work in his shipping container farm, Gateway Greens. AUL PHILPOTT, 25, has grown various veggies to empower young people to grow real food by help- on his farm, Gateway Greens, such as kale, col- ing them grow crops in vertical farms built in shipping P lard greens, Swiss chard, and a variety of herbs, containers.