Executive Doctorate “Perceived Environmental Uncertainty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

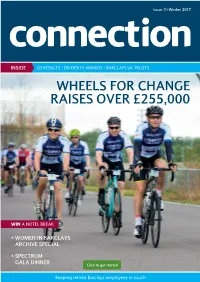

Connection Issue 70.Pdf

Issue 70 Winter 2017 connection INSIDE Q3 RESULTS • DIVERSITY AWARDS • BARCLAYS UK TRUSTS WHEELS FOR CHANGE RAISES OVER £255,000 WIN A HOTEL BREAK + WOMEN IN BARCLAYS ARCHIVE SPECIAL + SPECTRUM GALA DINNER Click to get started Keeping retired Barclays employees in touch Inside this issue... EDITOR’S WORD FEATURES REGULARS 5 10 Page 6 Page 4 Barclays news Barclays news Q3 2016 Results, The new £5 note, Barclays Diversity Wheels for Change, Spectrum’s Gala Business Awards 2016 Dinner and Pension Fund newsletter Page 8 Pensioners’ clubs & contacts Happy New Year to you all and welcome Page 12 Bournemouth and District Pensioners’ to the first edition of connection for Archive article 2017. We hope you’ve enjoyed the festive Club, Cornwall Pensioners’ Club, Women in Barclays season and are ready to embrace the Liverpool Retired Staff Club, East New Year. Midlands Pensioners’ Club and Many of you will be reading connection Ipswich District Pensioners’ Club on your computer or tablet screens for the Page 14 first time. To help you move through the Page 16 magazine more easily, we’ve added arrows Life beyond Your letters Barclays to the bottom of the pdf, and we’ve also Page 20 made the clickable links bold to make it The end of an era clear when you can click through to Retirements & obituaries other websites. Please let the Barclays Page 26 Team at Willis Towers Watson know if you Useful contacts no longer wish to receive a printed copy. If you’re thinking of embarking on a new Page 28 adventure this year, turn to pages 14 Competition & crossword and 15 for some Life beyond Barclays inspiration. -

![Here Could Be a Recognition Only of What I Have Called External Goods […]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5187/here-could-be-a-recognition-only-of-what-i-have-called-external-goods-1425187.webp)

Here Could Be a Recognition Only of What I Have Called External Goods […]

Competition and the London Clearing Banks, 1946-1979 Linda Arch © [email protected] The Court Room, The Bank of England https://www.flickr.com/photos/ba nkofengland/6220545302, accessed 3 May, 2015 1 Should Nation States Compete? 25-26 June 2015 Structure 1. Introduction 2. Context 3. Attitudes towards competition in clearing banking - ambivalence 4. Attitudes towards competition in clearing banking - embracing competition 5. Discussion and questions 2 Should Nation States Compete? 25-26 June 2015 1. INTRODUCTION 3 Should Nation States Compete? 25-26 June 2015 Alasdair MacIntyre Credit: Sean. https://www.flickr.com/p hotos/seanoconnor365/33 51618688 4 Should Nation States Compete? 25-26 June 2015 Introduction • “without the virtues there could be a recognition only of what I have called external goods […]. And in any society which recognised only external goods competitiveness would be the dominant and even exclusive feature.” • Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory, Third Edition, (Notre Dame, IND: University of Notre Dame Press, 2007), 196. 5 Should Nation States Compete? 25-26 June 2015 Introduction External goods: • ‘goods of effectiveness’ • profit, money, share price, status, prestige … • property or possession of an individual Internal goods: • ‘goods of excellence’ • achieved in the context of ‘practices’ • benefit the whole community who take part in that practice • Eg. an internal good in clearing banking might be the good of ‘trustworthiness’ 6 Should Nation States Compete? 25-26 June 2015 Introduction -

The Grasshopper Pensioners' Club Just As We Have For

THE GRASSHOPPER PENSIONERS’ CLUB Website: www.martinsbank.co.uk © gut informiert! SECRETARY: David Baldwin, Lower Windle, Windle Royd Lane, Warley, HX2 7LY. 'Phone: 01422 832734. email: [email protected] CHAIRMAN: Bernard Lovewell TREASURER: Robert Bunn WELFARE OFFICER: Susan Sutcliffe New Year Edition 2021 JUST AS WE HAVE MORE MEMORIES On this occasion from 1951 when our two best- FOR BEEN 458 YEARS, represented Districts in our membership met in WE’RE STILL HERE WITH their annual match, where the following photograph and comments were cut from their magazine by Joan and Gordon Anthony: The annual match between Liverpool and London Districts took place on Monday 8th October on the ground of the Odyssey WE WILL REMEMBER THEM THE MARTINS BANK WAR MEMORIAL In our last edition we mentioned the rededication of our War Memorial in 54 Lombard Street we are now attempting to identify its current location. Club in Liverpool, the kick-off being taken by Mr. J.A. Banks, the Liverpool District Manager. Fog, which persisted all day, lifted just before the match began and the game took place in brilliant sunshine but with a rather strong breeze across the pitch. Liverpool pressed strongly from the beginning and after fifteen minutes they were rewarded with a goal by Smith, the left winger, from an opening made by Bass, who had headed across the goal mouth. Play was fairly even for the next twenty minutes and then London broke away and Anthony, the centre forward, scored for the visitors. Both goal-keepers had more to do in the second half and had it not been the good work of Ford, the keeper for London, who made two excellent saves, the visitors would probably have been defeated, whereas the match ended in a draw. -

Analysing Risk Management in Banks: Evidence of Bank Efficiency

British Journal of Economics, Finance and Management Sciences 1 March 2017, Vol. 13 (2) The Nature and Extent of the Reciprocal Obligations Involved in the Banker/Customer Relationship Stanyo Dinov Abstract The current paper explores the banker/customer relationship and its historical development. Based on statuary and case law, it outlines the definitions of banker and customer, the duration of their relationship and their individual rights and obligations. Recent changes of the relationship and the differences, resulting from court decisions in England and Scotland regarding their obligations, are also presented. The article also trays to predict the possible changes to the banker/customer relationship in the near future. The most important conclusions, as well as possible further developments, are outlined at the end. Keywords: BEA, CCA, JCR, BPS, ATM systems I. Introduction The relationship between the banker and the customer has changed over time, so it is not easy to predict the nature of this relationship in the near future. Recent rapid technological development has raised many questions about customers‟ privacy and protection. Therefore, there is still a need to closely examine the legal aspects of this relationship from the past to the present, in order to find the best approach to its future context. II. Definition, nature and formation of reciprocal obligation 1. Definition The banker/customer relationship consists of two sides. A banker, according to the Bills of Exchange Act (BEA) 1882 s 2, „includes a body of persons whether -

Barclays PLC Rights Issue Prospectus

THIS PROSPECTUS AND ANY ACCOMPANYING DOCUMENTS ARE IMPORTANT AND REQUIRE YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. If you are in any doubt as to the action you should take, you are recommended to seek immediately your own personal financial advice from your stockbroker, bank manager, solicitor, accountant, fund manager or other appropriate independent financial adviser, who is authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (the “FSMA”) if you are in the UK or, if not, from another appropriately authorised independent financial adviser. If you sell or have sold or otherwise transferred all of your Existing Ordinary Shares (other than ex-rights) held in certificated form before 18 September 2013 (the “Ex-Rights Date”) please send this Prospectus, together with any Provisional Allotment Letter, duly renounced, if and when received, at once to the purchaser or transferee or to the bank, stockbroker or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected for delivery to the purchaser or transferee except that such documents should not be sent to any jurisdiction where to do so might constitute a violation of local securities laws or regulations. If you sell or have sold or otherwise transferred all or some of your Existing Ordinary Shares (other than ex-rights) held in uncertificated form before the Ex-Rights Date, a claim transaction will automatically be generated by Euroclear UK which, on settlement, will transfer the appropriate number of Nil Paid Rights to the purchaser or transferee. If you sell or have sold or otherwise transferred only part of your holding of Existing Ordinary Shares (other than ex-rights) held in certificated form before the Ex-Rights Date, you should refer to the instruction regarding split applications in Part II “Terms and Conditions of the Rights Issue” of this Prospectus and in the Provisional Allotment Letter, if and when received. -

Unit 8: Duties, Liabilities and Protection of Bankers in Handling Bills of Exchange

Unit 8: Duties, Liabilities and Protection of Bankers in Handling Bills of Exchange Payment of Cheques The legal position of a bank paying a cheque may be considered by looking at the contract of the bank with its customer; and the provisions of the Bills of Exchange Act Cap. 68 The legal relationships involving the paying bank may include: • That with its customer • That with some remote true owner of the cheque • That with the collecting bank Item (iii) is covered in Unit 9. Item (i) and (ii) relates to the contract the bank has with its customer as well as the statutory provisions in the BEA. The banker therefore needs to exercise a reasonable degree of care and skill when conducting its customer’s account. The cheque must be validly signed in order for the bank to have evidence of its customer’s authority (Catlin v Cyprus Finance Corporation London Ltd (1983)) to pay, (and in order for it to be covered by the BEA). By s. 2(4)a of the BEA, a cheque need not be dated at all. The paying bank has a right to insert a date under s. 19(1), although in practice, it is safer for the bank to return the cheque unpaid, stating ‘not dated’. By s.12 (2) of the BEA, a post-dated cheque is within the legal definition of a cheque as there is no contradiction with it being payable on demand – Royal Bank of Scotland v Tottenham (1894). Banks in practice do not honour cheques dated more than six months in the past marking them as ‘stale’, and whereas a case may be brought against the bank for dishonouring its customer’s instructions, this would be seen to be an implied term of the Banker/customer contract not to pay six months after date. -

The Grasshopper Pensioners' Club

THE GRASSHOPPER PENSIONERS’ CLUB Website: www.martinsbank.co.uk © gut informiert! SECRETARY: David Baldwin, Lower Windle, Windle Royd Lane, Warley, HX2 7LY. 'Phone: 01422 832734. email: [email protected] CHAIRMAN: Bernard Lovewell TREASURER: Robert Bunn WELFARE OFFICER: Susan Sutcliffe Easter Edition 2021 NO MATTER WHAT IS THROWN (and subject to unforeseen circumstances) our AT US AND AT OUR BANK, 2021 Lunch programme will resume as follows: LIVERPOOL 29th JUNE DESPITE THE RENAMING OF ONE KEIGHLEY 14th JULY OF OUR BRANCHES*, WE STILL LONDON SPRING 9th SEPTEMBER HAVE: LONDON 25th NOVEMBER MANCHESTER 1st DECEMBER Without your continued support we will be unable to both function and provide our lunches. We urge you to continue to support our efforts to provide our subsidised lunches where you can meet your former colleagues but only when it is safe for us and we are free to do so. (More details follow on Page 11) (JOKINGLY) DID A NORTH/SOUTH WE HOPE THAT YOU ARE ALL DIVIDE EXIST IN 1958? KEEPING FIT AND READY TO ENJOY These photographs, of the Liverpool v London ATTENDING OUR LUNCHES AND Districts’ rugby match, were published in the December edition and Peter Noble ‘phoned, as I MEETING YOUR FRIENDS AGAIN. was putting the finishing touches to the Spring (JUST LIKE THIS LITTLE FELLOW). Newsletter, to identify himself (second left, front row). Although Peter recognised some of his team-mates he couldn’t recall their names with the exception of ‘Chalky’ White. Can you help to provide the names of both teams, which were not mentioned in the original publication? LUNCHES UPDATE Following the various announcements by the Government on 22nd February, about the easing of COVID restrictions, which will hopefully allow us all to return to a ‘normal’ life. -

Built on Commerce: Liverpool's Central Business District

BUILT ON COMMERCE Liverpool’s central business district Published by English Heritage, Kemble Drive, Swindon SN2 2GZ www.english-heritage.org.uk English Heritage is the Government’s statutory adviser on all aspects of the historic environment. © English Heritage 2008 Printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Images (except as otherwise shown) © English Heritage, © English Heritage. NMR or © Crown copyright. NMR. First published 2008 ISBN 978 1 905624 34 8 Product code 51331 Liverpool Vision has made a financial contribution towards the publication of this book. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Front cover Application for the reproduction of images should be made to the National Monuments Record. Every Commercial palaces of Castle Street.The effort has been made to trace the copyright holders and we apologise in advance for any unintentional former Adelphi Bank, 1891–2, is on the omissions, which we would be pleased to correct in any subsequent edition of this book. left; the former Leyland & Bullin’s Bank, 1895, on the right. Behind them The National Monuments Record is the public archive of English Heritage. For more information, rises India Buildings, 1923–30. contact NMR Enquiry and Research Services, National Monuments Record Centre, Kemble Drive, [AA029367] Swindon SN2 2GZ; telephone (01793) 414600. -

1062255 May 2010 No. 45 ISSN: 1745 7556

Bulletin May 2010 No. 45 ISSN: 1745 7556 Reg. Charity Comm. No.: 1062255 War Memorials Trust works to protect and conserve all war memorials within the UK Objectives of War Memorials Trust 1. To monitor the condition of war memorials and to encourage protection and conservation when appropriate. Bulletin 2. To provide expert advice to those involved in war memorial ISSN: 1745-7556; Published quarterly by projects, to act as the specialist organisation for war memorial War Memorials Trust conservation issues and to facilitate repair and conservation 42a Buckingham Palace Road through grants schemes. London SW1W 0RE 3. To work with relevant organisations to encourage them to Telephone administration: 020 7834 0200 accept responsibility for war memorials and recognise the Telephone conservation: 020 7233 7356 need to undertake repair and conservation work. Telephone charity: 0300 123 0764 Fax: 020 7834 0202 or 0300 123 0765 4. To build a greater understanding of war memorial heritage and raise awareness of the issues surrounding war memorial Email: [email protected] or [email protected] conservation. Web: www.warmemorials.org Membership rates Registered Charity Commission No.: 1062255 War Memorials Trust membership rates are: Patron HRH The Duchess of Cornwall Area Vice Patrons £20 annual member; Diana Graves (England), £30 joint annual member and Sara Jones CBE (England), £100 for a lifetime subscription. Maj. Gen. the Rev Llewellyn CB OBE (Wales), Admiral Roger Lockwood (Scotland), The Lord Molyneaux of Killead KBE PC (N. I.), Photo credits front cover: Simon Weston OBE (Wales). Clifton war memorial, Bedfordshire © Clifton Parish Council, 2010 (WM2616). The project received £2,500 from the Small Trustees Grants Scheme towards repairs following damage to the war J. -

Composition Payments to Bankers

Composition payments to bankers On 1 st January 1970, when the National Westminster Bank Act 1969 took effect, there came to an end a series of annual payments made to bankers under the Bank Charter Act 1844 as compensation for relinquishing their right of note issue. Such payments were known at the time as 'composition'. Before 1844 the Bank had already made arrangements with some bankers to relinquish their note issues, and to some of these composition was already payable. Section 23 of the Bank Charter Act provided that it was payable hence forth to the forty-three bankers listed in Schedule C of the Act who had come to such an arrangement. The Act fixed the rate and method by which composition payments should be calculated. Under the 1844 Act, composition payments were to cease in 1856, but the Bankers' Compositions Act of that year effectively extended such payments indefinitely. One of the main objectives of the 1844 Act was to restrict as far as possible the note issues of banks in England and Wales other than the Bank of England. No new bank of issue was allowed; any banker ceasing to issue could not resume; and the note issue of any banker who elected to continue could not be increased. Section 24 of the Act encouraged bankers who had the right to issue notes to give up this privilege and to accept annual composition payments as compensation. Although a number of private issuing bankers wished to continue issuing notes on grounds of profitability, prestige and useful advertisement, their issues had already started to decline before 1844 in the face of competition from joint stock banks newly authorised by the Country Bankers Act of 1826 - whose resources were mainly derived from the taking of deposits - and the Bank of England's own network of branches. -

Descendants of Richard Crewdson

Descendants of Richard Crewdson Charles E. G. Pease Pennyghael Isle of Mull Descendants of Richard Crewdson 1-Richard Crewdson1 died in 1700. Noted events in his life were: • He had a residence in Crook, Kendal, Cumbria. Richard married Ann Ellwood1 in 1677 in Crook, Kendal, Cumbria. Ann died in 1730 in Crook, Kendal, Cumbria. They had four children: John, Ann, Agnes, and Sarah. General Notes: 11. 4. 1730. Anne Crewdson of Crook. Parish of Ky Kendall. (Died 1730). The name sometimes appears as Crudson or Croudson. Messuage and Tenement upon which I now dwell (late in the possession of Jonathan Thompson) Scituate at the Low End of Crook in the Parish of Kendal (Lands of Lord Viscount Lonsdale, yearly fhneable rent of 1/3, and also 2/4 for the Mill-stead) to my Daughter Sarah Crewdson and her heirs. Personal Estate. To Daughter in Law Margaret Crewdson 20/. To my five Grand-children John, Bryan, Isaac, Jonathan and Margaret Crewdson 20/- each. To my Daughter Anne Garnett wife of John G. £30. To Daughter Agnes Robinson wife of George R. £35. To John Garnett's children 2/6 each. Residue and all my Goods Credits Cattels and Chattells to my Daughter Sarah Crewdson subject to payment of debts etc. Executrix. Sarah Crewdson. Supervisors. John Thompson and Thomas Morland both of Crook (2/6 each). Inventory. Personal. Purse and Apparrell £4. 10. 0. Debts due to ye Deceased £115. Furniture. A chest and Table and Chayres 10/-. Goods in the Buttery 10/-. Goods in the Chamber £2. 10. 0. Implements. -

Martins Bank, Water Street, Liverpool

Martins Bank, Water Street, Liverpool MARTINS BANK, LIVERPOOL Created by: Jonathon Wild Campaign Director – Maelstrom www.maelstromdesign.co.uk 1 Martins Bank, Water Street, Liverpool CONTENTS SUMMARY………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 THOMAS GRESHAM….…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 WATER STREET……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 MARTINS BANK………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………6 HERBERT J ROWSE………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….7 MARTINS BANK HQ WATER STREET……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….8 MARTINS BANK – CONT…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………9 SELECTED IMAGES…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………10 – 22 2 Martins Bank, Water Street, Liverpool SUMMARY Martins Bank, located on Water Street, Liverpool, is a grade 2 listed building and former bank. Its location is on the corner of Water Street and Exchange Street West. Construction started in 1927, this was the head office for Martins Bank which was a replacement for the Bank of Liverpool Bank as this building was not able to cope with the demands of the banking services of the public. The building fronts on a very busy thoroughfare on Water Street. Water Street being one of the original seven streets of Liverpool (High Street, Chapel Street, Water Street, Castle Street, Dale Street, Tithebarn Street, Old Hall Street) which made the ‘H’ shape of the earliest roads in Liverpool. Water Street itself formerly called Bonk (Bank) Street which led to the original bank of the river Mersey. The building was in use till 2009 when the branch was disbanded. It has remained empty to this day and previous proposals on making use for the building have stalled. Martins Bank building is passed by thousands of workers each day, but one must inspect the Slave relief and wonder what part that must play in the history of the building. There is controversy over these sculptures of which we will come to later in a separate chapter.