Unit 8: Duties, Liabilities and Protection of Bankers in Handling Bills of Exchange

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chronology, 1963–89

Chronology, 1963–89 This chronology covers key political and economic developments in the quarter century that saw the transformation of the Euromarkets into the world’s foremost financial markets. It also identifies milestones in the evolu- tion of Orion; transactions mentioned are those which were the first or the largest of their type or otherwise noteworthy. The tables and graphs present key financial and economic data of the era. Details of Orion’s financial his- tory are to be found in Appendix IV. Abbreviations: Chase (Chase Manhattan Bank), Royal (Royal Bank of Canada), NatPro (National Provincial Bank), Westminster (Westminster Bank), NatWest (National Westminster Bank), WestLB (Westdeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale), Mitsubishi (Mitsubishi Bank) and Orion (for Orion Bank, Orion Termbank, Orion Royal Bank and subsidiaries). Under Orion financings: ‘loans’ are syndicated loans, NIFs, RUFs etc.; ‘bonds’ are public issues, private placements, FRNs, FRCDs and other secu- rities, lead managed, co-managed, managed or advised by Orion. New loan transactions and new bond transactions are intended to show the range of Orion’s client base and refer to clients not previously mentioned. The word ‘subsequently’ in brackets indicates subsequent transactions of the same type and for the same client. Transaction amounts expressed in US dollars some- times include non-dollar transactions, converted at the prevailing rates of exchange. 1963 Global events Feb Canadian Conservative government falls. Apr Lester Pearson Premier. Mar China and Pakistan settle border dispute. May Jomo Kenyatta Premier of Kenya. Organization of African Unity formed, after widespread decolonization. Jun Election of Pope Paul VI. Aug Test Ban Take Your Partners Treaty. -

Connection Issue 70.Pdf

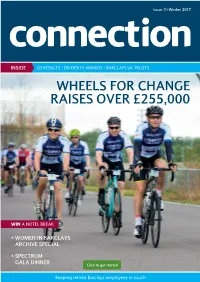

Issue 70 Winter 2017 connection INSIDE Q3 RESULTS • DIVERSITY AWARDS • BARCLAYS UK TRUSTS WHEELS FOR CHANGE RAISES OVER £255,000 WIN A HOTEL BREAK + WOMEN IN BARCLAYS ARCHIVE SPECIAL + SPECTRUM GALA DINNER Click to get started Keeping retired Barclays employees in touch Inside this issue... EDITOR’S WORD FEATURES REGULARS 5 10 Page 6 Page 4 Barclays news Barclays news Q3 2016 Results, The new £5 note, Barclays Diversity Wheels for Change, Spectrum’s Gala Business Awards 2016 Dinner and Pension Fund newsletter Page 8 Pensioners’ clubs & contacts Happy New Year to you all and welcome Page 12 Bournemouth and District Pensioners’ to the first edition of connection for Archive article 2017. We hope you’ve enjoyed the festive Club, Cornwall Pensioners’ Club, Women in Barclays season and are ready to embrace the Liverpool Retired Staff Club, East New Year. Midlands Pensioners’ Club and Many of you will be reading connection Ipswich District Pensioners’ Club on your computer or tablet screens for the Page 14 first time. To help you move through the Page 16 magazine more easily, we’ve added arrows Life beyond Your letters Barclays to the bottom of the pdf, and we’ve also Page 20 made the clickable links bold to make it The end of an era clear when you can click through to Retirements & obituaries other websites. Please let the Barclays Page 26 Team at Willis Towers Watson know if you Useful contacts no longer wish to receive a printed copy. If you’re thinking of embarking on a new Page 28 adventure this year, turn to pages 14 Competition & crossword and 15 for some Life beyond Barclays inspiration. -

The Headquarters of National Provincial Bank of England

Symbolism in bank marketing and architecture: the headquarters of National Provincial Bank of England Article Published Version Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 (CC-BY) Open Access Barnes, V. and Newton, L. (2019) Symbolism in bank marketing and architecture: the headquarters of National Provincial Bank of England. Management and Organizational History, 14 (3). pp. 213-244. ISSN 1744-9359 doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17449359.2019.1683038 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/86938/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17449359.2019.1683038 Publisher: Taylor and Francis All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Management & Organizational History ISSN: 1744-9359 (Print) 1744-9367 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rmor20 Symbolism in bank marketing and architecture: the headquarters of National Provincial Bank of England Victoria Barnes & Lucy Newton To cite this article: Victoria Barnes & Lucy Newton (2019) Symbolism in bank marketing and architecture: the headquarters of National Provincial Bank of England, Management & Organizational History, 14:3, 213-244, DOI: 10.1080/17449359.2019.1683038 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/17449359.2019.1683038 © 2019 The Author(s). -

Name of Deceased

Date before which Name of Deceased Address, description and date of death of Deceased Names, addresses and descriptions of Persons to whom notices of claims are to be given notices of claim (Surname first) • and names, in parentheses, of Personal Representatives ' ' to be given LLOYD, May Emily Kenwyn Lodge, Western Road, Fortis Green, National Provincial Bank Limited, 8 Howland Street, Tottenham Court Road, London 28th August 1964 Middlesex, Spinster. 8th June 1964. W.I. (092) PHILLIPS, Mary Flat 3, St. John's Court, Westcliff Parade, Westcliff- Howard Kennedy & Co., 23 Harcourt House, 19 Cavendish Square, London W.I. 3rd September 1964 on-Sea, Essex, Widow. 14th October 1963. (David Crystall and Harry Howard, LL.B.) (093) WARD, Constance Annie 8 Calverley Park, Tunbridge Wells, Kent, Widow, Burton & Ramsden, 81 Piccadilly, London W.I, Solicitors. (James Hildebrand'Ramsden 28th August 1964 Henrietta. llth November 1963. and Jack Bridgeland.) (094) H W SCHOFIELD, William 35 Fitzmauriae Road, Christchurch, Hampshire, Barrington Myers & Partners, Lloyds Bank Chambers, Christchurch, Hampshire, 28th August 1964 1 Arthur. Pilot. 18th February 1964. Solicitors. (Mary Dorothy Anne Schofield.) (095) r o TURNER, Maud Violet The Nosegay, Abersoch, Caernarvonshire, Spinster. Robyns Owen & Son, 36 High Street, Pwllheli, Caernarvonshire, Solicitors. (National 29th August 1964 Breen. 26th May 1964. Provincial Bank Limited.) (096) THOMPSON, Thojnas ... 108 Ponteland Road, Newcastle upon Tyne, General National Provincial Bank Limited, Trustee Branch, 26 Mosley Street, Newcastle upon 27th August 1964 Dealer. 6th June 1964. Tyne. (097) NEILLY, William John... 95 St. Ladoc Road, Keynsham, Bristol, Retired National Provincial Bank Limited, Trustee Branch, 36 Corn Street, Bristol 1, or 27th August 1964 I Clerk. -

Heritage Statement

Heritage Statement Overview The application is for the refurbishment and reconfiguration of the existing NatWest Bank located at 21 EastGate Street Standishsgate, Gloucester. NatWest’s first branch in Gloucester originally opened as a branch of National Provincal Bank of England in 1834. Gloucester at this time was a manufacturing centre with extensive dockyards, and was known for its pin-making industry. The city was also home to a growing number of iron foundries producing agricultural and milling implements for the surrounding area. The population of Gloucester had been increasing steadily throughout the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and by 1831 the city had over 14,000 inhabitants. National Provincial Bank of England had been founded in London in September 1833. From the outset it intended to establish a nationwide network of branches, and Gloucester was to be its very first. The branch opened in King Street on 1 January 1834. It was an immediate success, and even though the traditional industries in the city began to decline in the middle part of the nineteenth century, the construction trades flourished. Following the coming of the railway to Gloucester in 1840, the city also became known for the manufacture of railway carriages. By 1843 increasing demand for banking services in Gloucester meant that the branch had outgrown its original King Street premises. A new purpose-built branch building was erected in Westgate Street, completed in 1844. The branch’s business continued to grow rapidly throughout the nineteenth century, and in 1890 it relocated again to more spacious newly-constructed premises at 21 Eastgate Street. -

![Here Could Be a Recognition Only of What I Have Called External Goods […]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5187/here-could-be-a-recognition-only-of-what-i-have-called-external-goods-1425187.webp)

Here Could Be a Recognition Only of What I Have Called External Goods […]

Competition and the London Clearing Banks, 1946-1979 Linda Arch © [email protected] The Court Room, The Bank of England https://www.flickr.com/photos/ba nkofengland/6220545302, accessed 3 May, 2015 1 Should Nation States Compete? 25-26 June 2015 Structure 1. Introduction 2. Context 3. Attitudes towards competition in clearing banking - ambivalence 4. Attitudes towards competition in clearing banking - embracing competition 5. Discussion and questions 2 Should Nation States Compete? 25-26 June 2015 1. INTRODUCTION 3 Should Nation States Compete? 25-26 June 2015 Alasdair MacIntyre Credit: Sean. https://www.flickr.com/p hotos/seanoconnor365/33 51618688 4 Should Nation States Compete? 25-26 June 2015 Introduction • “without the virtues there could be a recognition only of what I have called external goods […]. And in any society which recognised only external goods competitiveness would be the dominant and even exclusive feature.” • Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory, Third Edition, (Notre Dame, IND: University of Notre Dame Press, 2007), 196. 5 Should Nation States Compete? 25-26 June 2015 Introduction External goods: • ‘goods of effectiveness’ • profit, money, share price, status, prestige … • property or possession of an individual Internal goods: • ‘goods of excellence’ • achieved in the context of ‘practices’ • benefit the whole community who take part in that practice • Eg. an internal good in clearing banking might be the good of ‘trustworthiness’ 6 Should Nation States Compete? 25-26 June 2015 Introduction -

The Commercial Banking Industry and Its Part in the Emergence

The Commercial Banking Industry and its part in the emergence and consolidation of the Corporate Economy in Britain before 1940 Journal of Industrial History, 3(2)The (2000) Commercial Banking Industry in Britain before 1940 Peter Wardley University of the West of England, Bristol ‘He did not think the banks had yet explored the enormous possibilities of mechanical methods. He thought the counter work at English banks was about as efficient as they could ever get, but he was suspicious as to whether they were as up to date behind the counter. He could see the banks of the future as possessing physical bodies of wonderfully contrived mechanism, almost everything of routine being done by machinery with the brains for the personal convenience of customers, and scientific conditions of control, a great civil service with a high tradition of public service, with opportunities for development and employment of many different talents. On the other hand, it was conceivable they might develop into mere money making machines.’ John Maynard Keynes, ‘The future opportunities of the bank official’; presented at the Cambridge Centre of the Institute of Banking; reported in the Cambridge Daily News, 15 October 1927; and, reprinted as ‘Mr J. M. Keynes on banking services’ in the Journal of the Institute of Banking, November 1927, vol. xlviii, p. 497. Banks engage in business which is intended to organise the profitable production of financial services and, like other privately-owned firms in a market economy, employ capital and labour to achieve this objective. Furthermore, as in other companies, it is within banks that more efficient combinations of capital and labour generate productivity growth. -

1914 and 1939

APPENDIX PROFILES OF THE BRITISH MERCHANT BANKS OPERATING BETWEEN 1914 AND 1939 An attempt has been made to identify as many merchant banks as possible operating in the period from 1914 to 1939, and to provide a brief profle of the origins and main developments of each frm, includ- ing failures and amalgamations. While information has been gathered from a variety of sources, the Bankers’ Return to the Inland Revenue published in the London Gazette between 1914 and 1939 has been an excellent source. Some of these frms are well-known, whereas many have been long-forgotten. It has been important to this work that a comprehensive picture of the merchant banking sector in the period 1914–1939 has been obtained. Therefore, signifcant efforts have been made to recover as much information as possible about lost frms. This listing shows that the merchant banking sector was far from being a homogeneous group. While there were many frms that failed during this period, there were also a number of new entrants. The nature of mer- chant banking also evolved as stockbroking frms and issuing houses became known as merchant banks. The period from 1914 to the late 1930s was one of signifcant change for the sector. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), 361 under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2018 B. O’Sullivan, From Crisis to Crisis, Palgrave Studies in the History of Finance, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96698-4 362 Firm Profle T. H. Allan & Co. 1874 to 1932 A 17 Gracechurch St., East India Agent. -

The Grasshopper Pensioners' Club Just As We Have For

THE GRASSHOPPER PENSIONERS’ CLUB Website: www.martinsbank.co.uk © gut informiert! SECRETARY: David Baldwin, Lower Windle, Windle Royd Lane, Warley, HX2 7LY. 'Phone: 01422 832734. email: [email protected] CHAIRMAN: Bernard Lovewell TREASURER: Robert Bunn WELFARE OFFICER: Susan Sutcliffe New Year Edition 2021 JUST AS WE HAVE MORE MEMORIES On this occasion from 1951 when our two best- FOR BEEN 458 YEARS, represented Districts in our membership met in WE’RE STILL HERE WITH their annual match, where the following photograph and comments were cut from their magazine by Joan and Gordon Anthony: The annual match between Liverpool and London Districts took place on Monday 8th October on the ground of the Odyssey WE WILL REMEMBER THEM THE MARTINS BANK WAR MEMORIAL In our last edition we mentioned the rededication of our War Memorial in 54 Lombard Street we are now attempting to identify its current location. Club in Liverpool, the kick-off being taken by Mr. J.A. Banks, the Liverpool District Manager. Fog, which persisted all day, lifted just before the match began and the game took place in brilliant sunshine but with a rather strong breeze across the pitch. Liverpool pressed strongly from the beginning and after fifteen minutes they were rewarded with a goal by Smith, the left winger, from an opening made by Bass, who had headed across the goal mouth. Play was fairly even for the next twenty minutes and then London broke away and Anthony, the centre forward, scored for the visitors. Both goal-keepers had more to do in the second half and had it not been the good work of Ford, the keeper for London, who made two excellent saves, the visitors would probably have been defeated, whereas the match ended in a draw. -

Analysing Risk Management in Banks: Evidence of Bank Efficiency

British Journal of Economics, Finance and Management Sciences 1 March 2017, Vol. 13 (2) The Nature and Extent of the Reciprocal Obligations Involved in the Banker/Customer Relationship Stanyo Dinov Abstract The current paper explores the banker/customer relationship and its historical development. Based on statuary and case law, it outlines the definitions of banker and customer, the duration of their relationship and their individual rights and obligations. Recent changes of the relationship and the differences, resulting from court decisions in England and Scotland regarding their obligations, are also presented. The article also trays to predict the possible changes to the banker/customer relationship in the near future. The most important conclusions, as well as possible further developments, are outlined at the end. Keywords: BEA, CCA, JCR, BPS, ATM systems I. Introduction The relationship between the banker and the customer has changed over time, so it is not easy to predict the nature of this relationship in the near future. Recent rapid technological development has raised many questions about customers‟ privacy and protection. Therefore, there is still a need to closely examine the legal aspects of this relationship from the past to the present, in order to find the best approach to its future context. II. Definition, nature and formation of reciprocal obligation 1. Definition The banker/customer relationship consists of two sides. A banker, according to the Bills of Exchange Act (BEA) 1882 s 2, „includes a body of persons whether -

A “Quiet Victory”: National Provincial, Gibson Hall, and the Switch from Comprehensive Redevelopment to Urban Preservation in 1960S London

A “Quiet Victory”: National Provincial, Gibson Hall, and the Switch from Comprehensive Redevelopment to Urban Preservation in 1960s London VICTORIA BARNES LUCY NEWTON PETER SCOTT © The Author 2020. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Business History Conference. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is unaltered and is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press must be obtained for commercial reuse or in order to create a derivative work. doi:10.1017/eso.2020.35 VICTORIA BARNES is a senior research fellow at the Max Planck Instutite for European Legal History, Frankfurt, Germany. She works on the history of business, its form and regulation in law and society. Her recent work can be read in the Journal of Corporation Law, Hastings Business Law Journal, Company Lawyer, and the Journal of Legal History. Contact information: Max-Planck-Institute for European Legal History, Hansaallee 41, Frankfurt am Main, Hesse 60323, Germany. E-mail: [email protected]. LUCY NEWTON is professor of business history at Henley Business School, University of Reading. She has published her work on banks and nineteenth-century consumer durables in a variety of business history journals. Her journal article, with Francesca Carnevali, “Pianos for the People,” was the winner of the Oxford Journals Article Prize for Best Paper in Enterprise and Society (2013), awarded March 2014. Contact information: University of Reading, Reading, Berkshire, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. -

Barclays PLC Rights Issue Prospectus

THIS PROSPECTUS AND ANY ACCOMPANYING DOCUMENTS ARE IMPORTANT AND REQUIRE YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. If you are in any doubt as to the action you should take, you are recommended to seek immediately your own personal financial advice from your stockbroker, bank manager, solicitor, accountant, fund manager or other appropriate independent financial adviser, who is authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (the “FSMA”) if you are in the UK or, if not, from another appropriately authorised independent financial adviser. If you sell or have sold or otherwise transferred all of your Existing Ordinary Shares (other than ex-rights) held in certificated form before 18 September 2013 (the “Ex-Rights Date”) please send this Prospectus, together with any Provisional Allotment Letter, duly renounced, if and when received, at once to the purchaser or transferee or to the bank, stockbroker or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected for delivery to the purchaser or transferee except that such documents should not be sent to any jurisdiction where to do so might constitute a violation of local securities laws or regulations. If you sell or have sold or otherwise transferred all or some of your Existing Ordinary Shares (other than ex-rights) held in uncertificated form before the Ex-Rights Date, a claim transaction will automatically be generated by Euroclear UK which, on settlement, will transfer the appropriate number of Nil Paid Rights to the purchaser or transferee. If you sell or have sold or otherwise transferred only part of your holding of Existing Ordinary Shares (other than ex-rights) held in certificated form before the Ex-Rights Date, you should refer to the instruction regarding split applications in Part II “Terms and Conditions of the Rights Issue” of this Prospectus and in the Provisional Allotment Letter, if and when received.