Bexar County College Readiness/Enrollment Patterns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021-2022 High School Course Catalog | Pathway Guide

2021-2022 HIGH SCHOOL COURSE CATALOG | PATHWAY GUIDE THE GUIDE TO HIGH SCHOOL COURSES AND PROGRAMS DESIGNED TO HELP STUDENTS BUILD A SUCCESSFUL FUTURE. It is the policy of Judson Independent School District not to discriminate on the basis of age, race, religion, color, national origin, sex or handicap in its programs, services, or activities as required by Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended; Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972; and Section 504 of theRehabilitation Act of 1973, as amended. Vision Judson ISD is Producing Excellence! Mission All Judson ISD students will receive a quality education enabling them to become successful in a global society Judson ISD Values • Students First • Teamwork • Accountability • Results-Oriented • Loyalty • Integrity & Mutual Respect • Safe & Secure Environment • Two-way Communication Judson ISD Driven by Excellence ©Judson ISD High School Course Catalog BOARD OF EDUCATION Renee A. Paschall, President Suzanne Kenoyer, Vice President Jennifer Rodriguez, Secretary Shatonya King, Trustee Debra Eaton, Trustee Rafael Diaz, Jr., Trustee Vacant, Trustee ADMINISTRATION Dr. Jeanette Ball, Superintendent of Schools William Atkins, Chief Financial Officer Cecilia Davis, Assistant Superintendent of Curriculum & Instruction Dr. Milton Fields, Deputy Superintendent of Administration & Operations Marco Garcia, Assistant Superintendent of Human Resources Rebecca Robinson, Deputy Superintendent of Teaching & Learning Dr. Nicole Taguinod, Chief Communications Officer A special thank you to all of the individuals who contributed and provided feedback on the course catalog: Professional School Counselors, Curriculum Specialists, Departments of Career and Technology, Fine Arts, Curriculum & Instruction, and Guidance & Counseling. ©Judson ISD High School Course Catalog Introduction The Judson Independent School District Course Catalog lists the courses that our high schools generally make available to students. -

Texas Association of Collegiate Registrars & Admissions Officers

TACRAO 2009 Texas Association of Collegiate Registrars & Admissions Officers 2009-2010 College Day/Night Schedule of Programs 2 TEXAS ASSOCIATION OF COLLEGIATE REGISTRARS AND ADMISSIONS OFFICERS 2009-2010 COLLEGE DAY/NIGHT PROGRAMS High School-College Relations Committee Kyle B Moore, Chair West Texas A&M University WTAMU Box 60907 Canyon, TX 79016 [email protected] One copy of this schedule is provided to each TACRAO member institution and subscription institution. Note: Receipt of this schedule does not constitute invitation to the high school or community college program. 3 TACRAO College Day/Night Schedule 2009-2010 High School-College Relations Committee Kyle B Moore, Chair West Texas A&M University WTAMU Box 60907 Canyon, TX 79016 Dates TEA Districts Area and # of Reps. Coordinator Fall 2009 Sept. 8-11 19 El Paso (2) Michael Talamantes University of Texas at El Paso El Paso, Texas Sept. 14-18 10 Dallas (4) Randall R. Nunn University of North Texas Denton, Texas 1 Rio Grande Valley (1) Leticia Bazan Texas A&M Univ.-Corpus Christi Corpus Christi, Texas Sept. 21-25 10 Dallas (4) Randall R. Nunn University of North Texas Denton, Texas 2 Coastal Bend (1) Leticia Bazan Texas A&M Univ.-Corpus Christi Corpus Christi, Texas Sept. 28-Oct. 2 14, 15 & 18 West Texas (1) Trey Wetendorf Odessa College Odessa, Texas 16 & 17 Panhandle (2) Rene Ralston Texas State Technical College Sweetwater, Texas Oct. 5-9 4 & 6 Houston (4) Sophia Polk Sam Houston State University Huntsville, Texas 7 & 8 Central Texas (3) Alexandria Alley University of Texas at Austin Austin, Texas 4 Dates TEA Districts Area and # of Reps. -

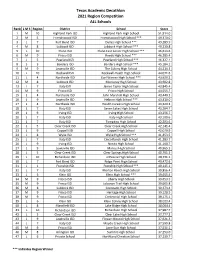

2020-2021 State Scores

Texas Academic Decathlon 2021 Region Competition ALL Schools Rank L M S Region District School Score 1M 10 Highland Park ISD Highland Park High School 51,914.0 2M 5 Friendswood ISD Friendswood High School *** 49,370.0 3L 7 Fort Bend ISD Dulles High School *** 49,289.9 4M 8 Lubbock ISD Lubbock High School *** 49,230.8 5L 10 Plano ISD Plano East Senior High School *** 46,613.6 6M 9 Frisco ISD Reedy High School *** 46,385.4 7L 5 Pearland ISD Pearland High School *** 46,327.1 8S 3 Bandera ISD Bandera High School *** 45,184.1 9M 9 Lewisville ISD The Colony High School 44,214.3 10 L 10 Rockwall ISD Rockwall‐Heath High School 44,071.6 11 L 4 Northside ISD Earl Warren High School *** 43,929.2 12 M 8 Lubbock ISD Monterey High School 43,902.8 13 L 7 Katy ISD James Taylor High School 43,845.4 14 M 9 Frisco ISD Frisco High School 43,555.7 15 L 4 Northside ISD John Marshall High School 43,440.3 16 L 9 Lewisville ISD Hebron High School *** 43,410.0 17 L 4 Northside ISD Health Careers High School 43,320.3 18 L 7 Katy ISD Seven Lakes High School 43,264.7 19 L 9 Irving ISD Irving High School 43,256.7 20 L 7 Katy ISD Katy High School 43,109.6 21 L 7 Katy ISD Tompkins High School 42,203.6 22 L 5 Clear Creek ISD Clear Creek High School 42,141.4 23 L 9 Coppell ISD Coppell High School 42,070.9 24 L 8 Wylie ISD Wylie High School *** 41,453.5 25 L 7 Katy ISD Cinco Ranch High School 41,283.7 26 L 9 Irving ISD Nimitz High School 41,160.7 27 L 9 Lewisville ISD Marcus High School 40,965.3 28 L 5 Clear Creek ISD Clear Springs High School 40,761.3 29 L 10 Richardson -

Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate Examination Results in Texas 2008-09

Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate Examination Results in Texas 2008-09 Division of Accountability Research Department of Assessment, Accountability, and Data Quality Texas Education Agency May 2010 Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate Examination Results in Texas 2008-09 Project Staff Amanda Callinan Shawn Thomas Editorial Staff Anthony Grasso Richard Kallus Christine Whalen Division of Accountability Research Department of Assessment, Accountability, and Data Quality Texas Education Agency May 2010 Texas Education Agency Robert Scott, Commissioner of Education Lizzette Reynolds, Deputy Commissioner for Statewide Policy and Programs Department of Assessment, Accountability, and Data Quality Criss Cloudt, Associate Commissioner Office of Data Development, Analysis, and Research Patricia Sullivan, Deputy Associate Commissioner Division of Accountability Research Linda Roska, Director Citation. Texas Education Agency. (2010). Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate examination results in Texas, 2008-09 (Document No. GE10 601 07). Austin, TX: Author. Abstract. This report reviews Advanced Placement (AP) and International Baccalaureate (IB) examination participation and performance in Texas during the 2008-09 school year. Campus-, district-, and state-level examination results for students in Texas public schools are presented, as well as state-level examination results for students in Texas public and nonpublic schools combined. The report discusses the use of AP and IB examination results in college admissions and the Academic Excellence Indicator System. It also provides descriptions and brief histories of the AP and IB programs, along with a brief history of state policy and funding related to the AP and IB programs in Texas. Keywords. Advanced placement, international baccalaureate, credit by examination, testing, incentive, high school, financial need, scores, gifted and talented. -

Texas Special Events List

TEXAS SPECIAL EVENTS LIST Event Name Start Date End Date City County Site Size Region 1 Texas Christian University NCAA Division I Baseball 2/1/2021 6/1/2021 Fort Worth Tarrant 6,000 AT&T Byron Nelson Golf Tournament 5/10/2021 5/16/2021 Mckinney Collin 12,000 C-10 Nationals 5/13/2021 5/15/2021 Fort Worth Tarrant 15,000 Tops in Texas Rodeo 5/14/2021 5/15/2021 Jacksonville Cherokee 5,000 Thoroughbred Horse Racing - Preakness Stakes 5/14/2021 5/16/2021 Grand Prairie Dallas 10,000 Irving Concert Series 5/14/2021 5/14/2021 Irving Dallas 1,500 Irving Concert Series 4 Kids 5/14/2021 5/14/2021 Irving Dallas 1,500 MS 150 5/15/2021 5/15/2021 Frisco Collin 3,000 Movies in the Park 5/15/2021 7/17/2021 Mesquite Dallas 500 Bark & Paws 5/15/2021 5/15/2021 Denison Grayson 500 Admire Walk & Wine 5/15/2021 5/15/2021 Denison Grayson 250 Geekend 5/15/2021 5/15/2021 Kilgore Gregg 1,500 Old Fiddler's and Reunion 5/15/2021 5/15/2021 Athens Henderson 300 Boonstock Annual Fundraiser 5/15/2021 5/15/2021 Bridgeport Wise 750 Decatur Band Banquet 5/15/2021 5/15/2021 Decatur Wise 750 Jacksboro Prom 5/15/2021 5/15/2021 Decatur Wise 750 Summer Musical 5/15/2021 5/16/2021 Mineola Wood 150 Tena Vogel Dance Recital 5/16/2021 5/16/2021 Longview Gregg 2,000 Wise County Crime Stoppers Clay Shoot 5/16/2021 5/16/2021 Decatur Wise 2,500 MLB: 2021 Texas Rangers 5/17/2021 5/17/2021 Arlington Tarrant 49,115 James Taylor with Jackson Browne 5/17/2021 5/17/2021 Fort Worth Tarrant 14,000 Mounted Patrol School 5/18/2021 5/22/2021 Athens Henderson 20 MLB: 2021 Texas Rangers 5/18/2021 -

San Antonio Area Monday, October 25, 2010 Tuesday, October 267, 2010

San Antonio Area District 20 Monday, October 25, 2010 1:00 PM -3:00 PM Hondo High School 2603 Ave. H Hondo, TX 78861 Includes nine area schools 6:30 PM – 8:00 PM Alamo Heights High School 6900 Broadway San Antonio, TX 78209 6:00 PM -8:30 PM Northside ISD The University of Texas at San Antonio Campus Recreation Facility San Antonio, Texas 78249 Jay, Holmes, Health Careers, Warren, Clark, Marshall, O’Conner, Business Careers, Communication Arts, Stevens, Taft, Brandies Tuesday, October 267, 2010 1:00 PM -3:00 PM Somerset High School 1650 S. Loop 1604 West Somerset, TX 78069 1:00 PM -3:00 PM Fredricksburg High School 1107 Hwy 16 South Fredricksburg, TX 78624 Evening 6:00 PM -8:00 PM Tivy High School 325 Loop 534 Kerrville, TX 78028 Ingram Tom Moore, Junction,Medina, Rocksprings, Harper, Comfort, Center Point Schools 6:00 PM -7:30 PM Judson ISD Karen Wagner High School 3000 N. Foster Road San Antonio, TX 78244 Wednesday, October 27, 2010 9:00 AM -11:00 AM Pearsall High School 1990 Maverick Drive Pearsall, TX 78061 1:00 PM -3:00 PM Atascosa-Medina County Fair, Lytle HS PO Box 190 Lytle, Texas 78052 Lytle, Natalia, Devine, & Poteet 6:00 PM -8:30 PM San Antonio ISD Alamo Convocation Center 110 Tuleta San Antonio, Texas Edison, Jefferson, Highlands,Burbank, Sam Houston, Brackenridge HS, Lanier, Fox Tech 6:00 PM -8:00 PM Northeast ISD Blossom Athletic Center /Littleton Gym 12002 Jones Maltsberger San Antonio, TX 78232 Churchill, Lee, Reagan, International School Of the Americas, Madison, Roosevelt, MacArthur Thursday, October 28, 2010 9:00 AM -10:30 AM The Winston School 8565 Ewing Halsell San Antonio, TX 78229 1:45 PM -2:45 PM Cornerstone Christian School 4802 Vance Jackson Street San Antonio, TX 78230 1:00 PM – 3:30 PM East Central High School 7173 FM 1628 San Antonio, TX 78263 210-649-2951 ext 2111 7:00 PM -9:00 PM Private Schools of San Antonio By Invitation Only St. -

Agenda of Regular Board Meeting August 16, 2018

Board Briefs is published to help keep staff and citizens informed about actions of the Judson Independent School District Board of Trustees. Agenda of Regular Board Meeting August 16, 2018 The Board of Trustees Judson ISD A Regular of the Board of Trustees of Judson ISD will be held August 16, 2018, beginning at 7:00 PM in the ERC Board Room, 8205 Palisades Dr., Live Oak, Texas. The subjects to be discussed or considered or upon which any formal action may be taken are listed below. Items do not have to be taken in the same order as shown on this meeting notice. Unless removed from the consent agenda, items identified within the consent agenda will be acted on at one time. 1. MEETING CALLED TO ORDER A. Roll Call, Establishment of Quorum, Invocation, Pledge of Allegiance 2. RECOGNITIONS-None 3. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF VISITORS/CITIZENS TO BE HEARD- None 4. CONSIDERATION OF CONSENT ITEMS A. Consider and take action regarding approving Minutes from the Special Board Meetings held on June 19, June 25, July 16 and the Regular Meeting held on June 21, 2018. B. Consider and take action regarding approving Monthly Financial Information as of July 31, 2018. This report includes Revenue and Expenditure (Budget vs. Actual) for the General Operating, Child Nutrition, and Interest & Sinking Funds; Estimated cash flow for the General Operating and Child Nutrition Funds; Cash reconciliation for the General Operating, Child Nutrition, Special Revenue, Interest & Sinking, and Construction Funds; Tax Collections status report. C. Consider and take action regarding approving Expenditures Equal to or Greater than $50,000. -

St. Philip's College Complies with All Guidelines Set Forth by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges

Office of the President December ϭϰ, 2020 Dr. Belle Wheelan, President Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges 1866 Southern Lane Decatur, GA 30033 Dear Dr. Wheelan, In accordance with the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges’ Principles of Accreditation: Foundations for Quality Enhancement, St. Philip’s College is pleased to request approval to offer students the opportunity to complete greater than 50% of the coursework required for a Level 1 Certificate for Inert Gas GTAW/GMAW Welder (MSGW) at the following high school locations: Bandera High School 474 Old San Antonio Hwy Bandera, Texas 78003 We anticipate that greater than 50% of the necessary coursework leading to a Level 1 Certificate for Inert Gas GTAW/GMAW Welder (MSGW) may be obtained by students beginning in the fall 2021 semester. I look forward to continually working to ensure that St. Philip's College complies with all guidelines set forth by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges. Please let me know if you have any questions or need any clarification. Sincerely, Adena Williams Loston, Ph.D. President C: Melissa Guerrero, Ph.D., SACSCOC Accreditation Liaison, St. Philips College 1801 Martin Luther King Drive, San Antonio, TX 78203-2098 ● Phone 210-486-2900 ● Fax 210-486-2590 COMPLETEONEFORMPERPROSPECTUSOR Complete,attachtosubmission,andsendto: CoverSheetforSubmissionof APPLICATIONSUBMITTED. Dr.BelleWheelan,President Forquestionsaboutthisform,contactthe SouthernAssociationofCollegesandSchools -

Report of High School Graduates' Enrollment and Academic

Report of 2006-2007 High School Graduates’ Enrollment and Academic Performance in Texas Public Higher Education in FY 2008 Texas statute requires every school district to include, with their performance report, information received under Texas Education Code §51.403(e). This information, provided to districts from the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board (THECB), reports on student performance in postsecondary institutions during the first year enrolled after graduation from high school. Student performance is measured by the Grade Point Average (GPA) earned by 2006- 2007 high school graduates who attended public four-year and two-year higher education in FY 2008. The data is presented alphabetically for each county, school district and high school. The bookmarks can be used to select the first letter of a county. Then the user can scroll down to the desired county, school district and high school. For each student, the grade points and college-level semester credit hours earned by a student in fall 2007, spring 2008, and summer 2008 are added together and averaged to determine the GPA. These GPAs are accumulated in a range of five categories from < 2.0 to > 3.5. If a GPA could not be calculated for some reason, that student is placed in the “Unknown” column. GPA data is only available for students attending public higher education institutions in Texas. If a high school has fewer than five students attending four-year or two-year public higher education institutions, the number of students is shown but no GPA breakout is given. If a student attended both a four-year and a two-year institution in FY 2008, the student’s GPA is shown in the type of institution where the most semester credit hours were earned. -

REPORT on HIGH SCHOOL ALLOTMENT: Review of Uses of High School Allotment Funds During the 2006-07 School Year

REPORT ON HIGH SCHOOL ALLOTMENT: Review of Uses of High School Allotment Funds during the 2006-07 School Year Evaluation Project Staff Andrew Moellmer Jim VanOverschelde, Ph.D Amie Rapaport, Ph.D Program Staff Jan Lindsey Jennifer Jacob Barbara Knaggs Office for Planning, Grants and Evaluation Texas Education Agency September 2008 Texas Education Agency Robert Scott, Commissioner of Education Office for Planning, Grants and Evaluation Nora Ibáñez Hancock, Ed.D, Associate Commissioner Division of Evaluation, Analysis, and Planning Ellen W. Montgomery, Ph.D, Division Director The Office for Planning, Grants & Evaluation wishes to thank all agency staff who contributed to this report. Citation. Texas Education Agency. (2008). Report on High School Allotment: Review of Uses of High School Allotment Funds during the 2006-07 School Year. Austin, TX: Author. Copyright © Notice The materials are copyrighted © and trademarked ™ as the property of the Texas Education Agency (TEA) and may not be reproduced without the express written permission of TEA, except under the following conditions: 1) Texas public school districts, charter schools, and Education Service Centers may reproduce and use copies of the Materials and Related Materials for the districts’ and schools’ educational use without obtaining permission from TEA. 2) Residents of the state of Texas may reproduce and use copies of the Materials and Related Materials for individual personal use only without obtaining written permission of TEA. 3) Any portion reproduced must be reproduced in its entirety and remain unedited, unaltered and unchanged in any way. 4) No monetary charge can be made for the reproduced materials or any document containing them; however, a reasonable charge to cover only the cost of reproduction and distribution may be charged. -

06 28 2018 SPC Cole Wagner AA

COMPLETE ONE FORM PER PROSPECTUS OR Complete, attach to submission, and send to: Cover Sheet for Submission of APPLICATION SUBMITTED. Dr. Belle Wheelan, President For questions about this form, contact the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Substantive Changes Substantive Change Office at 404.679.4501, Commission on Colleges ext. 4526, or email Dr. Kevin Sightler at 1866 Southern Lane Requiring Approval [email protected] Decatur, GA 30033 OFFICIAL NAME OF INSTITUTION MAIN CAMPUS CITY + STATE (OR NON‐U.S. COUNTRY) SUBMISSION DATE INTENDED STARTING (MM/DD/YYYY) DATE (MM/YYYY) Type of change (check the appropriate boxes) New program at the current degree level that is a significant departure from current programs FULL NAME OF PROPOSED PROGRAM (E.G.,CERTIFICATE IN CYBER SECURITY, BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN CIVIL ENGINEERING) New off‐campus instructional site where 50% or more of a program's credits are offered SITE NAME CITY STATE STREET ADDRESS ZIP COUNTRY Will the site be a branch campus? (see Substantive Change Policy, p. 16, for definition) Yes No Distance delivery: approval of the institution to offer 50% or more of programs electronically for the first time Competency‐based educational program in which 50% or more of the credit is offered by direct assessment (see "Direct Assessment Competency‐based Educational Programs" policy) Closing a program, instructional site, or institution Type of closure: Program closure Site closure Institution closure Degree Level Change (see Substantive Change Policy, p. 15, for definitions; -

U.S. Army Cadet Command JROTC Drill Championships Daytona Beach, Florida on April 30Th, 2021 Updated: 4/7/2021 2:15:48 PM School Name Instructor City/State

U.S. Army Cadet Command JROTC Drill Championships Daytona Beach, Florida on April 30th, 2021 Updated: 4/7/2021 2:15:48 PM School Name Instructor City/State 5th BDE Alamo Heights High School 1SG Jasper Miller San Antonio, TX 5th BDE Central Catholic High School MSG Herbert Robles San Antonio, TX 5th BDE Claudia Taylor Johnson High School CSM Richard Sizer San Antonio, TX 6th BDE Greenville High School SFC Reginald Williams Greenville, AL 5th BDE Highlands High School CSM Vincent McCormick San Antonio, TX 5th BDE Karen Wagner High School SFC Wayne Harper San Antonio, TX 4th BDE Lugoff Elgin High School 1SG James Stroud LUGOFF, SC 3rd BDE Marmion Academy MSG William Jones Aurora, IL 3rd BDE Missouri Military Academy SFC John Biddle Mexico, MO 6th BDE Murphy High School LTC Chevelle Thomas Mobile, AL 6th BDE Natchitoches Central High School 1SG Michael Selby Natchitoches, La 6th BDE Oasis High School CSM Paul Pratt Cape Coral, FL 3rd BDE Ozark High School MAJ Danny Cazier Ozark, MO 6th BDE Ridge Community High School 1SG Isaac Baumer Davenport, FL 6th BDE Ringgold High School SFC Larry Sisemore Ringgold, GA 5th BDE Ronald Reagan High School MSG John Tijerina San Antonio, TX 6th BDE Southwood High School SFC Russell Mason Shreveport, La 5th BDE Theodore Roosevelt High School MSG Marchantia Johnson SAN ANTONIO, TX 5th BDE Thomas Jefferson High School - CO MAJ Dennis Campbell Denver, Co 5th BDE Thomas Jefferson High School - TX LTC Tracy Chavis San Antonio, TX 6th BDE Ware County High School SFC Rena Riviere Waycross, GA 4th BDE West Forsyth High School MAJ Richard Sugg Clemmons, NC 5th BDE Winston Churchill High School CPT Keisha Spaulding San Antonio, TX.