Staring Into the Abyss? the State of UK Rugby's Super League

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Huddersfield Giants Vs Catalans Dragons Live Stream Super Rugby League Sports Watch Online-21-05-2017

Live*(((Online)))*Huddersfield Giants vs Catalans Dragons Live Stream Super Rugby League Sports Watch Online-21-05-2017 Huddersfield Giants vs Catalans Dragons; 8:00pm Wednesday 12th Searches related to Huddersfield Giants vs Catalans Dragons Live huddersfield giants live score huddersfield giants squad bbc sport bet365Catalans Dragons vs Huddersfield Giants; 5:00pm Saturday 10th June Huddersfield v Catalans Watch Catalans Dragons vs Huddersfield Giants LiveStream kick off the Online Telecast 2017 Live Stream Online games, Live, Rugby : Catalans Dragons v Huddersfield Giants LIVE Watch..Online..Click..To..Live..Here..videohdq.com/online-tv/ Watch..Online..Click..To..Live..Here..videohdq.com/online-tv/ (Watch~Live) Catalans Dragons - Huddersfield Giants Live Stream https://innovation150 ca//watchlive -catalans-dragons-huddersfield-giants-live-strea 36 mins ago - online WATCH LIVE NOW (Watch~Live) Catalans Dragons - Huddersfield Giants Live Stream Sign up or Log in to save your favourites!Jun 26 - Dec 17 QUANTUM: The Exhibition Catalans Dragons Huddersfield Giants live score, video stream and www sofascore com/catalans-dragons-huddersfield-giants/QJbsVid You can watch Catalans Dragons vs Huddersfield Giants live stream online if you are registered member of bet365, the leading online betting company that has Super League: Huddersfield Giants v Catalans Dragons - BBC Sport www bbc com/sport/live/rugby-league/39308021 Apr 12, 2017 - Listen to BBC Radio 5 live sports extra and local radio commentary of Huddersfield Giants v Catalans Dragons -

Theory of the Beautiful Game: the Unification of European Football

Scottish Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 54, No. 3, July 2007 r 2007 The Author Journal compilation r 2007 Scottish Economic Society. Published by Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main St, Malden, MA, 02148, USA THEORY OF THE BEAUTIFUL GAME: THE UNIFICATION OF EUROPEAN FOOTBALL John Vroomann Abstract European football is in a spiral of intra-league and inter-league polarization of talent and wealth. The invariance proposition is revisited with adaptations for win- maximizing sportsman owners facing an uncertain Champions League prize. Sportsman and champion effects have driven European football clubs to the edge of insolvency and polarized competition throughout Europe. Revenue revolutions and financial crises of the Big Five leagues are examined and estimates of competitive balance are compared. The European Super League completes the open-market solution after Bosman. A 30-team Super League is proposed based on the National Football League. In football everything is complicated by the presence of the opposite team. FSartre I Introduction The beauty of the world’s game of football lies in the dynamic balance of symbiotic competition. Since the English Premier League (EPL) broke away from the Football League in 1992, the EPL has effectively lost its competitive balance. The rebellion of the EPL coincided with a deeper media revolution as digital and pay-per-view technologies were delivered by satellite platform into the commercial television vacuum created by public television monopolies throughout Europe. EPL broadcast revenues have exploded 40-fold from h22 million in 1992 to h862 million in 2005 (33% CAGR). -

Leigh Centurions V ROCHDALE HORNETS

Leigh Centurions SUvN DRAOY C17HTDH AMLAREC H O20R1N9 @ET 3S PM # LEYTHERS # OURTOWNOURCLUB# OURTOWNOURCLUB # LEYTHERS # OURTOWNOURCLUB# OURTOWNOURCLUB engage with the fans at games and to see the players acknowledged for their efforts at the Toronto game, despite the narrowness of the defeat, was something Welcome to Leigh Sports Village for day 48 years ago. With a new community that will linger long in the memory. this afternoon’s Betfred stadium in the offing for both the city’s Games are coming thick and fast at FChamRpionshOip gameM agains t oTur HfootbEall team s iTt could Oalso welPl also be present and the start of our involvement in friends from Rochdale Hornets. the last time Leigh play there. the Corals Challenge Cup and the newly- Carl Forster is to be commended for It’s great to see the Knights back on the instigated 1895 Cup and the prospect of taking on the dual role of player and coach up after years in the doldrums and to see playing at Wembley present great at such a young age and after cutting his interest in the professional game revived opportunities and goals for Duffs and his teeth in two years at Whitehaven, where under James Ford’s astute coaching. players. The immediate task though is to he built himself a good reputation, he now Watching York back at their much-loved carry on the good form in a tight and has the difficult task of preserving Wiggington Road ground was always one competitive Championship where every Hornets’ hard-won Championship status in of the best away days in the season and I win is hard-earned and valuable. -

Official E-Programme

OFFICIAL E-PROGRAMME Versus Castleford Tigers | 16 August 2020 Kick-off 4.15pm 5000 BETFRED WHERE YOU SEE AN CONTENTS ARROW - CLICK ME! 04 06 12 View from the Club Roby on his 500th appearance Top News 15 24 40 Opposition Heritage Squads SUPER LEAGUE HONOURS: PRE–SUPER LEAGUE HONOURS: Editor: Jamie Allen Super League Winners: 1996, 1999, Championship: 1931–32, 1952–53, Contributors: Alex Service, Bill Bates, 2000, 2002, 2006, 2014, 2019 1958–59, 1965–66, 1969–70, 1970–71, Steve Manning, Liam Platt, Gary World Club Challenge Honours: 1974–75 Wilton, Adam Cotham, Mark Onion, St. Helens R.F.C. Ltd 2001, 2007 Challenge Cup: 1955–56, 1960–61, Conor Cockroft. Totally Wicked Stadium, Challenge Cup Honours: 1996, 1997, 1965–66, 1971–72, 1975–76 McManus Drive, 2001, 2004, 2006, 2007, 2008 Leaders’ Shield: 1964–65, 1965–66 Photography: Bernard Platt, Liam St Helens, WA9 3AL BBC Sports Team Of The Year: 2006 Regal Trophy: 1987–88 Platt, SW Pix. League Leaders’ Shield: 2005, 2006, Premiership: 1975–76, 1976–77, Tel: 01744 455 050 2007, 2008, 2014, 2018, 2019 1984–85, 1992–93 Fax: 01744 455 055 Lancashire Cup: 1926–27, 1953–54, Ticket Hotline: 01744 455 052 1960–61, 1961–62, 1962–63, 1963–64, Email: [email protected] 1964–65, 1967–68, 1968–69, 1984–85, Web: www.saintsrlfc.com 1991–92 Lancashire League: 1929–30, Founded 1873 1931–32, 1952–53, 1959–60, 1963–64, 1964–65, 1965–66, 1966–67, 1968–69 Charity Shield: 1992–93 BBC2 Floodlit Trophy: 1971–72, 1975–76 3 VIEW FROM THE CLUB.. -

The Tom Sephton Memorial Trophy

The Tom Sephton Memorial Trophy The Tom Sephton Memorial Trophy is a Charity Amateur Rugby League Match held in memoriam of Private Thomas Sephton. Tom was an Infantry Soldier in The Mortar Platoon, The 1st Battalion The Mercian Regiment (Cheshire) – 1 MERCIAN. Tragically Tom died in July 2010 as a result of the wounds he received in Afghanistan on Operation Herrick 12. Tom came from Penketh, Warrington and was an outstanding sportsman. For many years he played rugby for Crosfields Amateur Rugby League Football Club. At 18 Tom joined the army and went on to represent his Battalion where his skills and bravery on the rugby field drew admiration from all. It has been said of him that, “He was never one to shy away from any situation and put his body on the line for the team. He tackled well above his weight and was a pleasure to be with both on and off the pitch, a young man of honour with a wry sense of humor and a sharp wit, a man with courage that belied his stature and loyalty beyond measure”. Tom was a key and influential part of the 2006 Crosfields ARLFC Under 16‟s squad that swept all before them, winning the Under 16‟s North-West Counties League Championship and reaching the National Cup Semi-Final. From this squad an impressive number of Toms‟ team mates have gone on to achieve great things in their young rugby careers, playing professional Rugby League with Superleague clubs, Warrington Wolves, Saint Helens, Salford City Reds and Widnes Vikings. -

Round 232021

FRONTTHE ROW ROUND 23 2021 VOLUME 2 · ISSUE 24 PARTY AT THE BACK Backs and halves dominate the Run rabbit run rookie class of 2021 TheBiggestTiger zones in on a South Sydney superstar! INSIDE: ROUND 23 PROGRAM - SQUAD LISTS, PREVIEWS & HEAD TO HEAD STATS, R22 REVIEWED LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM AUSTRALIA’S LEADING INDEPENDENT RUGBY LEAGUE WEBSITE THERE IS NO OFF-SEASON 2 | LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM | THE FRONT ROW | VOL 2 ISSUE 24 What’s inside From the editor THE FRONT ROW - VOL 2 ISSUE 24 Tim Costello From the editor 3 It's been an interesting year for break-out stars. Were painfully aware of the lack of lower-grade rugby league that's been able Feature Rookie Class of 2021 4-5 to be played in the last 18 months, and the impact that's going to have on development pathways in all states - particularly in History Tommy Anderson 6-7 New South Wales. The results seems to be that we're getting a lot more athletic, backline-suited players coming through, with Feature The Run Home 8 new battle-hardened forwards making the grade few and far between. Over the page Rob Crosby highlights the Rookie Class Feature 'Trell' 9 of 2021 - well worth a read. NRL Ladder, Stats Leaders 10 Also this week thanks to Andrew Ferguson, we have a footy history piece on Tommy Anderson - an inaugural South Sydney GAME DAY · NRL Round 23 11-27 player who was 'never the same' after facing off against Dally Messenger. The BiggestTiger's weekly illustration shows off the LU Team Tips 11 speed and skill of Latrell Mitchell, and we update the run home to the finals with just three games left til the September action THU Gold Coast v Melbourne 12-13 kicks off. -

The Rise of Leagues and Their Impact on the Governance of Women's Hockey in England

‘Will you walk into our parlour?’: The rise of leagues and their impact on the governance of women's hockey in England 1895-1939 Joanne Halpin BA, MA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Wolverhampton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Submission date: May 2019 This work or any part thereof has not previously been presented in any form to the University or to any other body for the purposes of assessment, publication or for any other purpose (unless otherwise indicated). Save for any express acknowledgements, references and/or bibliographies cited in the work, I confirm that the intellectual content of the work is the result of my own efforts and of no other person. The right of Jo Halpin to be identified as author of this work is asserted in accordance with ss.77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. At this date copyright is owned by the author. Signature: …………………………………….. Date: ………………………………………….. Jo Halpin ‘Will you walk into our parlour?’ Doctoral thesis Contents Abstract i List of abbreviations iii Acknowledgements v Introduction: ‘Happily without a history’ 1 • Hockey and amateurism 3 • Hockey and other team games 8 • The AEWHA, leagues and men 12 • Literature review 15 • Thesis aims and structure 22 • Methodology 28 • Summary 32 Chapter One: The formation and evolution of the AEWHA 1895-1910 – and the women who made it happen 34 • The beginnings 36 • Gathering support for a governing body 40 • The genesis of the AEWHA 43 • Approaching the HA 45 • Genesis of the HA -

RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 1

rfl official guide 2012 working.e$S:RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 1 RFL Official Guide 201 2 rfl official guide 2012 working.e$S:RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 2 The text of this publication is printed on 100gsm Cyclus 100% recycled paper rfl official guide 2012 working.e$S:RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 1 CONTENTS Contents RFL B COMPETITIONS Index ........................................................... 02 B1 General Competition Rules .................. 154 RFL Directors & Presidents ........................... 10 B2 Match Day Rules ................................ 163 RFL Offices .................................................. 10 B3 League Competition Rules .................. 166 RFL Executive Management Team ................. 11 B4 Challenge Cup Competition Rules ........ 173 RFL Council Members .................................. 12 B5 Championship Cup Competition Rules .. 182 Directors of Super League (Europe) Ltd, B6 International/Representative Community Board & RFL Charities ................ 13 Matches ............................................. 183 Past Life Vice Presidents .............................. 15 B7 Reserve & Academy Rules .................. 186 Past Chairmen of the Council ........................ 15 Past Presidents of the RFL ............................ 16 C PERSONNEL Life Members, Roll of Honour, The Mike Gregory C1 Players .............................................. 194 Spirit of Rugby League Award, Operational Rules C2 Club Officials ..................................... -

Covid 19 (Coronavirus) Ticketing FAQ’S

Covid 19 (Coronavirus) Ticketing FAQ’s Public health considerations – for everyone - and particularly the most vulnerable in all our communities - are everyone’s priority. The Rugby Football League and Super League are following and have always followed Government’s advice and will continue to do so. We are in constant contact with the relevant Government Departments who are informed by the national scientific and medical experts. All tickets purchased with RFL ticketing are subject to the standard terms and conditions of sale which can be found on our ticketing website https://www.rugby- league.com/tickets/terms__conditions Please understand that due to the high volume of enquiries, our ticketing team is experiencing higher numbers of calls and emails at the current time and it may therefore take a little longer than normal for us to respond. We will endeavour to respond to all our customers within 72 hours at this time. We are working remotely in line with the government restrictions and we appreciate your patience. Dacia Magic Weekend Dacia Magic Weekend at St James’ Park is postponed. The event was due to make its return to Newcastle on May 23-24. Betfred Super League intends to keep Dacia Magic Weekend in the 2020 schedule and all options are being considered as part of extensive and ongoing fixtures remodelling. More information will be provided once there is a clearer picture regarding the resumption of the season. Tickets already bought for Dacia Magic Weekend in Newcastle will be transferable to a later date at St James’ Park, or an alternative venue depending on when the season restarts. -

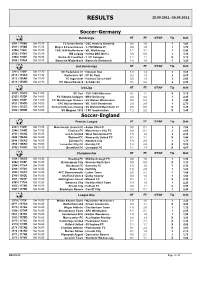

Results 25.09.2021.-26.09.2021

RESULTS 25.09.2021.-26.09.2021. Soccer-Germany Bundesliga HT FT OT/AP Tip Odd 2301 | 1358B Sat 15:30 FC Union Berlin - DSC Arminia Bielefeld 0:0 1:0 1 1,65 2303 | 1358D Sat 15:30 Bayer 04 Leverkusen - 1. FSV Mainz 05 0:0 1:0 1 1,70 2305 | 1358F Sat 15:30 TSG 1899 Hoffenheim - VfL Wolfsburg 1:1 3:1 1 2,50 2302 | 1358C Sat 15:30 RB Leipzig - Hertha BSC Berlin 3:0 6:0 1 1,30 2304 | 1358E Sat 15:30 Eintracht Frankfurt - 1. FC Cologne 1:1 1:1 X 3,75 2306 | 1359A Sat 18:30 Borussia M'gladbach - Borussia Dortmund 1:0 1:0 1 3,20 2nd Bundesliga HT FT OT/AP Tip Odd 2311 | 1359F Sat 13:30 SC Paderborn 07 - Holstein Kiel 1:0 1:2 2 3,65 2313 | 135AC Sat 13:30 Karlsruher SC - FC St. Pauli 0:2 1:3 2 2,85 2312 | 135AB Sat 13:30 FC Ingolstadt - Fortuna Düsseldorf 0:0 1:2 2 2,00 2314 | 135AD Sat 20:30 FC Hansa Rostock - Schalke 04 0:1 0:2 2 2,30 3rd Liga HT FT OT/AP Tip Odd 2323 | 135CF Sat 14:00 SC Verl - TSV 1860 München 0:1 1:1 X 3,75 2325 | 135DF Sat 14:00 FC Viktoria Cologne - MSV Duisburg 2:0 4:2 1 2,45 2326 | 135EF Sat 14:00 FC Wurzburger Kickers - SV Wehen Wiesbaden 0:0 0:4 2 2,40 2321 | 135CD Sat 14:00 1 FC Kaiserslautern - VfL 1899 Osnabrück 2:0 2:0 1 2,70 2322 | 135CE Sat 14:00 Eintracht Braunschweig - SV Waldhof Mannheim 07 0:0 0:0 X 3,25 2324 | 135DE Sat 14:00 SV Meppen 1912 - 1 FC Saarbrucken 1:2 2:2 X 3,40 Soccer-England Premier League HT FT OT/AP Tip Odd 2347 | 1369F Sat 13:30 Manchester United FC - Aston Villa FC 0:0 0:1 2 7,00 2346 | 1369E Sat 13:30 Chelsea FC - Manchester City FC 0:0 0:1 2 2,60 2351 | 136AE Sat 16:00 Leeds United - West -

SAINTS 2019 VIP MATCHDAY HOSPITALITY 2 2019 Matchday Hospitality

SAINTS 2019 VIP MATCHDAY HOSPITALITY 2 2019 Matchday Hospitality Welcome to St.Helens R.F.C. We are one of the oldest and most famous Rugby League Clubs in existence. Founded in 1873 we have a long and proud history of trophy winning teams and exhilarating, entertaining Rugby played by legends of the game. Our home, the Totally Wicked Stadium is our stage. We offer a VIP matchday experience unmatched within our sport. Enjoy an experience to cherish. We are Saints and Proud. 3 2019 Matchday Hospitality WE OFFER THE ULTIMATE VIP EXPERIENCE 4 2019 Matchday Hospitality AT AN INCREDIBLE VENUE 5 2019 Matchday Hospitality WITH AN ELECTRIC ATMOSPHERE 6 2019 Matchday Hospitality BEAUTIFUL FOOD 7 2019 Matchday Hospitality ON NIGHTS OF HIGH DRAMA 8 2019 Matchday Hospitality WATCHING HEROES 9 2019 Matchday Hospitality CLOSE UP 10 2019 Matchday Hospitality FROM THE BEST SEAT IN THE HOUSE 11 2019 Matchday Hospitality LAUGH! 12 2019 Matchday Hospitality CELEBRATE SPECIAL OCCASIONS 13 2019 Matchday Hospitality MEET LEGENDS 14 2019 Matchday Hospitality AND MAKE MEMORIES 15 2019 Matchday Hospitality CHOOSE YOUR PACKAGE HOSPITALITY 16 2019 Matchday Hospitality 1873 LOUNGE Join us in our 1873 Lounge YOUR PACKAGE INCLUDES: throughout the season for a Matchday experience that Premium padded match seats in 10% merchandise discount for offers great food, great the South Stand close to the half Saints Superstore (located at company and plenty to keep way line. the Totally Wicked Stadium) on you entertained… Matchday, just show your match Delicious pre-match three-course ticket in store to qualify. meal plus a tasting plate with complimentary tea & coffee at Our Lounge magician, John Holt PRICES (ALL PRICES +VAT) half-time and access to a private will visit your table and entertain cash bar. -

The Evolution of the Football Jersey – an Institutional Perspective

Journal of Institutional Economics (2021), 17, 821–835 doi:10.1017/S1744137421000278 RESEARCH ARTICLE The evolution of the football jersey – an institutional perspective David Butler and Robert Butler* Department of Economics, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] (Received 6 March 2020; revised 31 March 2021; accepted 2 April 2021; first published online 4 May 2021) Abstract This paper explores the interaction of informal constraints on human behaviour by examining the evolu- tion of English football jerseys. The jersey provides an excellent setting to demonstrate how informal con- straints emerge from formal rules and shape human behaviour. Customs, approved norms and habits are all observed in this setting. The commercialisation of football in recent decades has resulted in these infor- mal constraints, in many cases dating back over a century, co-existing with branding, goodwill and identity effects. Combined, these motivate clubs to maintain the status quo. As a result, club colours have remained remarkably resilient within a frequently changing landscape. Key words: Custom; football; habit; identity; jersey JEL codes: Z20; Z21 1. Introduction Association football, or football as it is more commonly known outside of North America, is an excel- lent example of an institution. Indeed, Douglas North used a metaphor derived from a sporting context when explaining institutions as ‘the rules of the game…to define the way the game is played. But the objective of the team within that set of rules is to win the game’ (North, 1990:3–5). Such a description is perfect for understanding how football is played.