Wood Anatomy of Echium (Boraginaceae) Sherwin Carlquist Claremont Graduate University; Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks Bioblitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks BioBlitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2016/1147 ON THIS PAGE Photograph of BioBlitz participants conducting data entry into iNaturalist. Photograph courtesy of the National Park Service. ON THE COVER Photograph of BioBlitz participants collecting aquatic species data in the Presidio of San Francisco. Photograph courtesy of National Park Service. The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks BioBlitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2016/1147 Elizabeth Edson1, Michelle O’Herron1, Alison Forrestel2, Daniel George3 1Golden Gate Parks Conservancy Building 201 Fort Mason San Francisco, CA 94129 2National Park Service. Golden Gate National Recreation Area Fort Cronkhite, Bldg. 1061 Sausalito, CA 94965 3National Park Service. San Francisco Bay Area Network Inventory & Monitoring Program Manager Fort Cronkhite, Bldg. 1063 Sausalito, CA 94965 March 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. -

Echium Candicans

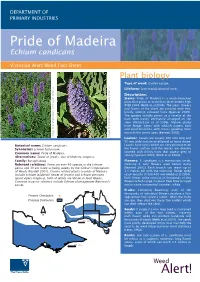

DEPARTMENT OF PRIMARY INDUSTRIES Pride of Madeira Echium candicans Victorian Alert Weed Fact Sheet Plant biology Type of weed: Garden escape. Lifeform: Semi-woody biennial herb. Description: Stems: Pride of Madeira is a much-branched plant that grows to more than three metres high (PIER 2004; Webb et al 2004). The stem, fl owers and leaves of the plant are covered with fi ne, bristly, whitish coloured hairs (Spencer 2005). The species initially grows as a rosette at the base with leaves alternately arranged on the stem (Richardson et al 2006). Mature plants have longer stems with whitish papery bark and stout branches, with leaves growing more towards the stem’s apex (Bennett 2003). Image: RG & FJ Richardson - www.weedinfo.com.au Image: RG & FJ Richardson - www.weedinfo.com.au Image: RG & FJ Richardson Leaves: Leaves are usually 200 mm long and 55 mm wide and are an ellipsoid or lance shape. Botanical name: Echium candicans. Leaves have veins which are very prominent on Synonyms: Echium fastuosum. the lower surface and the leaves are densely covered with bristly hairs that appear grey or Common name: Pride of Madeira. silvery (Spencer 2005; Webb et al 2004). Alternatives: Tower of jewels, star of Madeira, bugloss. Family: Boraginaceae. Flowers: E. candicans is a monocarpic shrub, Relevant relatives: There are over 40 species in the Echium meaning it only fl owers once before dying genus and 30 are listed as being weedy by the Global Compendium (Bennett 2003). Each branch can reach up to of Weeds (Randall 2001). Closely related plants to pride of Madeira 3.5 metres tall with the columnar fl ower spike include Echium wildpretii (tower of jewels) and Echium pininana reach lengths of 200-400 mm (Webb et al 2004). -

A. Hansen & P. Sunding Flora of Macaronesia. Checklist of Vascular Plants. 4. Revised Edition

DOI: 10.2478/som-1993-0003 sommerfeltia 17 A. Hansen & P. Sunding Flora of Macaronesia. Checklist of vascular plants. 4. revised edition 1993 sommerf~ is owned and edited by the Botanical Garden and Museum, University of Oslo. SOMMERFELTIA is named in honour of the eminent Norwegian botanist and clergyman S0ren Christian Sommerfelt (1794-1838). The generic name Sommerfeltia has been used in (1) the lichens by Florke 1827, now Solorina, (2) Fabaceae by Schumacher 1827, now Drepanocarpus, and (3) Asteraceae by Lessing 1832, nom. cons. SOMMERFELTIA is a series of monographs in plant taxonomy, phytogeography, phyto sociology, plant ecology, plant morphology, and evolutionary botany. Most papers are by Norwegian authors. Authors not on the staff of the Botanical Garden and Museum in Oslo pay a page charge of NOK 30. SOMMERFELTIA appears at irregular intervals, normally one article per volume. Editor: Rune Halvorsen 0kland. Editorial Board: Scientific staff of the Botanical Garden and Museum. Address: SOMMERFELTIA, Botanical Garden and Museum, University of Oslo, Trond heimsveien 23B, N-0562 Oslo 5, Norway. Order: On a standing order (payment on receipt of each volume) SOMMERFELTIA is supplied at 30 % discount. Separate volumes are supplied at prices given on pages inserted at the end of the volume. sommerfeltia 17 A. Hansen & P. Sunding Flora of Macaronesia. Checklist of vascular plants. 4. revised edition 1993 ISBN 82-7420-019-5 ISSN 0800-6865 Hansen, A. & Sunding, P. 1993. Flora of Macaronesia. Checklist of vascular plants. 4. revised edition. - Sommerfeltia 17: 1-295. Oslo. ISBN 82-7420-019-5. ISSN 0800-6865. An up-to-date checklist of the vascular plants of Macaronesia (the Azores, the Madeira archipelago, the Salvage Islands, the Canary Island, and the Cape Verde Islands) is given. -

Documento Informativo RESERVA NATURAL ESPECIAL DE PUNTALLANA PLAN DIRECTOR

P la n D ir e c to r Reserva Natural Especial de APROBACIÓN APROBACIPuntallanaÓN DEFINITIVA DDEFINITIVA oc um en to In fo rm at ivo RESERVA NATURAL ESPECIAL DE PUNTALLANA PLAN DIRECTOR INDICE DOCUMENTO INFORMATIVO 1. DESCRIPCIÓN DE LA RESERVA NATURAL ESPECIAL .................................. 3 1.1 INTRODUCCIÓN ...................................................................................... 3 1.2 MEDIO FÍSICO............................................................................................ 3 1.2.1. Situación geográfica y extensión..................................................... 3 1.2.2. Clima ............................................................................................. 3 1.2.3. Geología y geomorfología ............................................................. 4 1.2.4. Características morfológicas .......................................................... 7 1.2.5. Hidrología ....................................................................................... 8 1.2.6. Edafología ..................................................................................... 10 1.2.7. Paisaje. Unidades de paisaje ....................................................... 12 1.3 MEDIO BIOLÓGICO ................................................................................. 14 1.3.1. Flora y vegetación ......................................................................... 14 1.3.2. Fauna ............................................................................................ 23 1.3.3. Medio litoral ................................................................................ -

The Canary Islands

The Canary Islands Dragon Trees & Blue Chaffinches A Greentours Tour Report 7th – 16th February 2014 Leader Başak Gardner Day 1 07.02.2014 To El Patio via Guia de Isora I met the half of the group at the airport just before midday and headed towards El Guincho where our lovely hotel located. We took the semi coastal road up seeing the xerophytic scrub gradually changing to thermophile woodland and then turned towards El Teide mountain into evergreen tree zone where the main tree was Pinus canariensis. Finally found a suitable place to stop and then walked into forest to see our rare orchid, Himantoglossum metlesicsiana. There it was standing on its own in perfect condition. We took as many pics as possible and had our picnic there as well. We returned to the main road and not long after we stopped by the road side spotting several flowering Aeonium holochrysum. It was a very good stop to have a feeling of typical Canary Islands flora. We encountered plants like Euphorbia broussonetii and canariensis, Kleinia neriifolia, Argyranthemum gracile, Aeonium urbicum, Lavandula canariensis, Sonchus canariensis, Rumex lunaria and Rubia fruticosa. Driving through the windy roads we finally came to Icod De Los Vinos to see the oldest Dragon Tree. They made a little garden of native plants with some labels on and the huge old Dragon Tree in the middle. After spending some time looking at the plants that we will see in natural habitats in the following days we drove to our hotel only five minutes away. The hotel has an impressive drive that you can see the huge area of banana plantations around it. -

The Canary Islands

The Canary Islands Naturetrek Tour Report 6 - 13 March 2009 Indian Red Admiral – Vanessa indica vulcania Canary Islands Cranesbill – Geranium canariense Fuerteventura Sea Daisy – Nauplius sericeus Aeonium urbicum - Tenerife Euphorbia handiensis - Fuerteventura Report compiled by Tony Clarke with images by kind courtesy of Ken Bailey Naturetrek Cheriton Mill Cheriton Alresford Hampshire SO24 0NG England T: +44 (0)1962 733051 F: +44 (0)1962 736426 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report The Canary Islands Tour Leader: Tony Clarke (tour leader and naturalist) Tour Participants: Phil Haywood Hazel Haywood Peter Barrett Charles Wade Ken Bailey Day 1 Friday 6th March The arrival time of the group meant that we had enough time to do some birding in the afternoon and so we drove up from the airport, through Vilaflor to the Zona Recreativa de Las Lajas. This is probably the most well known location on Tenerife as it is where most people see their first Blue Chaffinches and we were not to be disappointed. Also at this location we saw the only Great Spotted Woodpecker of the tour plus a few Canaries, a Tenerife Kinglet and a few African Blue Tits. After departing from Las Lajas we continued climbing and entered the Las Cañadas National Park which is a spectacular drive through volcanic scenery. On the drive we encountered quite a few endemic plants including Pinus canariensis and Spartocytisus supranubius that were common and easily recognized and Echium wildpretii, Pterocephalus lasiospermus, Descurainia bourgaeana and Argyranthemum teneriffae which were rather unimpressive as they were not yet flowering but we were compensated by the fabulous views across the ancient caldera. -

Cold Hardiness of Climatic Zone 9 Plants at 53' North Latitude David Robinson, Ph

ISSUE 70 SESGNO!.IA Cold Hardiness of Climatic Zone 9 Plants at 53' North Latitude David Robinson, Ph. D. This article is based on a talk Dr. Robinson gave at the Annual Meeting of the Magnolia Society in Ireland, March zoot. Although my garden at Earlsdiffe, Baily, Co Dublin is situated at 53' 3' north latitude, it has a favorable microdimate and contains many cimatic zone 9 (USDA) plants. The harsh 2000/2001 winter, the most severe since I started taking records in 1969, provided a good opportu- nity to record the effect of low temperatures on many marginally hardy plants. The 2000/01 Winter Autumn 2000 was mild and wet with temperatures well above average in early December. However, on the night of December 26/27, 2000, the air temperature fell to —6 'C (21.2 'F) and to -4 'C (24.8 'F), -7 'C (19.4 'F), -5.5 'C (22. 1 'F) and -4.5 'C (23.9 'F) on the following four nights. For the three days between the 28s and 30" of December the tempera- ture never rose above -3 or -4 'C (26.5 or 25 'F) during the day. At the end of the cold speB (December 30+), the temperature rose 7.5 'C (13 'F) during the night and was 3 'C (37 'F) by morning, so the speed of thaw was rapid. After a relatively mild January, another cold spell began on February 23/24, 2001 and the minimum air temperatures recorded on this, and the following nine days, were: -2 'C (28.4 'F), -2 'C (28,4 F'), —1. -

Plant Biodiversity of Zarm-Rood Rural

ﻋﺒﺎس ﻗﻠﯽﭘﻮر و ﻫﻤﮑﺎران داﻧﺸﮕﺎه ﮔﻨﺒﺪ ﮐﺎووس ﻧﺸﺮﯾﻪ "ﺣﻔﺎﻇﺖ زﯾﺴﺖ ﺑﻮم ﮔﯿﺎﻫﺎن" دوره ﭘﻨﺠﻢ، ﺷﻤﺎره دﻫﻢ، ﺑﻬﺎر و ﺗﺎﺑﺴﺘﺎن 96 http://pec.gonbad.ac.ir ﺗﻨﻮع ﮔﯿﺎﻫﯽ دﻫﺴﺘﺎن زارمرود، ﺷﻬﺮﺳﺘﺎن ﻧﮑﺎ (ﻣﺎزﻧﺪران) ﻋﺒﺎس ﻗﻠﯽﭘﻮر1*، ﻧﺴﯿﻢ رﺳﻮﻟﯽ2، ﻣﺠﯿﺪ ﻗﺮﺑﺎﻧﯽ ﻧﻬﻮﺟﯽ3 1داﻧﺸﯿﺎر ﮔﺮوه زﯾﺴﺖﺷﻨﺎﺳﯽ، داﻧﺸﮑﺪه ﻋﻠﻮم، داﻧﺸﮕﺎه ﭘﯿﺎم ﻧﻮر، ﺗﻬﺮان 2 داﻧﺶآﻣﻮﺧﺘﻪ ﮐﺎرﺷﻨﺎﺳﯽارﺷﺪ ﻋﻠﻮم ﮔﯿﺎﻫﯽ، داﻧﺸﮑﺪه ﻋﻠﻮم، داﻧﺸﮕﺎه ﭘﯿﺎم ﻧﻮر، ﺗﻬﺮان 3اﺳﺘﺎدﯾﺎر ﭘﮋوﻫﺶ، ﻣﺮﮐﺰ ﺗﺤﻘﯿﻘﺎت ﮔﯿﺎﻫﺎن داروﯾﯽ، ﭘﮋوﻫﺸﮑﺪه ﮔﯿﺎﻫﺎن داروﯾﯽ ﺟﻬﺎد داﻧﺸﮕﺎﻫﯽ، ﮐﺮج ﺗﺎرﯾﺦ درﯾﺎﻓﺖ: 12/10/1394؛ ﺗﺎرﯾﺦ ﭘﺬﯾﺮش: 1395/12/19 ﭼﮑﯿﺪه1 دﻫﺴﺘﺎن ز ارمرود در ﺑﺨﺶ ﻫﺰارﺟﺮﯾﺐ ﺷﻬﺮﺳﺘﺎن ﻧﮑﺎ (اﺳﺘﺎن ﻣﺎزﻧﺪران)، ﻗﺮار دارد. اﯾﻦ دﻫﺴﺘﺎن ﻣﻨﻄﻘـﻪ اي ﮐﻮﻫﺴﺘﺎﻧﯽ ﺑﺎ ﻣﺴﺎﺣﺘﯽ ﺣﺪود 609 ﮐﯿﻠﻮﻣﺘﺮ ﻣﺮﺑﻊ، در داﻣﻨﻪ ارﺗﻔﺎﻋﯽ 1700 ﺗﺎ 2100 ﻣﺘﺮ از ﺳﻄﺢ درﯾﺎ ﻗـﺮار ﮔﺮﻓﺘـﻪ اﺳﺖ. ﺑﺮاي ﻣﻄﺎﻟﻌﻪ ﻓﻠﻮر ﻣﻨﻄﻘﻪ، ﻧﻤﻮﻧﻪﻫﺎي ﮔﯿﺎﻫﯽ ﻃﯽ ﺳﺎلﻫﺎي 1391 و1392، ﺟﻤﻊآوري و ﺑﺎ اﺳـﺘﻔﺎده از ﻣﻨـﺎﺑﻊ ﻣﻌﺘﺒﺮ ﻓﻠﻮرﺳﺘﯿﮏ ﺷﻨﺎﺳﺎﯾﯽ ﺷﺪﻧﺪ. در ﻣﺠﻤﻮع 172 ﮔﻮﻧﻪ، ﻣﺘﻌﻠﻖ ﺑﻪ 146 ﺟﻨﺲ از 69 ﺗﯿﺮه ﺷﻨﺎﺳﺎﯾﯽ ﺷـﺪ. ﺗ ﯿـ ﺮه Fabaceae ﺑﺎ داﺷﺘﻦ 12 ﺟﻨﺲ و 16 ﮔﻮﻧﻪ از ﺑﺰرﮔﺘﺮﯾﻦ ﺗﯿ ﺮهﻫﺎي ﻣﻨﻄﻘﻪ ﻣﺤﺴﻮب ﻣ ﯽﺷﻮد. از ﻧﻈﺮ ﺷﮑﻞ زﯾﺴـﺘ ﯽ، 37 درﺻﺪ از ﮔﻮﻧﻪﻫﺎ ﻫﻤ ﯽﮐﺮﯾﭙﺘﻮﻓﯿﺖ، 26 درﺻﺪ ﻓﺎﻧﺮوﻓﯿﺖ، 19 درﺻﺪ ﮐﺮﯾﭙﺘﻮﻓﯿﺖ، 17 درﺻﺪ ﺗﺮوﻓﯿﺖ و 1 درﺻﺪ ﮐﺎﻣ ﻪﻓﯿﺖ ﻫﺴﺘﻨﺪ. ﻓﺮاواﻧﯽ ﮔﻮﻧﻪﻫﺎي ﻓﺎﻧﺮوﻓﯿﺖ ﺑﺎ وﺿﻌﯿﺖ ﻃﺒﯿﻌﯽ ﭘﻮﺷﺶ ﮔﯿﺎﻫﯽ ﻣﻨﻄﻘﻪ ﯾﻌﻨﯽ ﻏﻠﺒﻪ رﯾﺨﺘﺎر ﺟﻨﮕﻠﯽ ﻫﻤﺨﻮاﻧﯽ دارد. ﺑﺮ اﺳﺎس ﺗﻮزﯾﻊ ﺟﻐﺮاﻓﯿﺎي ﮔﯿﺎﻫﯽ، 36 درﺻﺪ از ﮔﻮﻧﻪﻫﺎ ﻋﻨﺼﺮ روﯾﺸﯽ ﻧﺎﺣﯿﻪ ارو - ﺳـ ﯿﺒﺮي، Downloaded from pec.gonbad.ac.ir at 6:30 +0330 on Friday October 1st 2021 23 درﺻﺪ از ﮔﻮ ﻧﻪﻫﺎ ﭼﻨﺪ ﻧﺎﺣﯿ ﻪاي، 16 درﺻﺪ ﺑﻪ ﻃﻮر ﻣﺸﺘﺮك ﻋﻨﺼﺮ روﯾﺸﯽ ﻧﺎﺣﯿﻪ ارو - ﺳﯿﺒﺮي و اﯾﺮان- ﺗﻮراﻧﯽ، 14 درﺻﺪ اﯾﺮان – ﺗﻮراﻧﯽ و 2 درﺻﺪ ﺟﻬﺎن وﻃﻨﯽ ﻣ ﯽﺑﺎﺷﻨﺪ. -

Être' of Toxic Secondary Compounds in the Pollen of Boraginaceae

Received: 1 November 2019 | Accepted: 11 April 2020 DOI: 10.1111/1365-2435.13581 RESEARCH ARTICLE To bee or not to bee: The ‘raison d'être’ of toxic secondary compounds in the pollen of Boraginaceae Vincent Trunz1 | Matteo A. Lucchetti1,2 | Dimitri Bénon1 | Achik Dorchin3 | Gaylord A. Desurmont4 | Christina Kast2 | Sergio Rasmann1 | Gaétan Glauser5 | Christophe J. Praz1 1Institute of Biology, University of Neuchatel, Neuchatel, Switzerland Abstract 2Agroscope, Swiss Bee Research Centre, 1. While the presence of secondary compounds in floral nectar has received consid- Bern, Switzerland erable attention, much less is known about the ecological significance and evolu- 3The Steinhardt Museum of Natural History, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel tionary origin of secondary ‘toxic’ compounds in pollen. It is unclear whether the 4European Biological Control Laboratory, presence of these compounds in pollen is non-adaptive and due to physiological USDA ARS, Montferrier-Sur-Lez, France ‘spillover’ from other floral tissues, or whether these compounds serve an adap- 5Neuchatel Platform of Analytical tive function related to plant–pollinator interactions, such as protection of pollen Chemistry, University of Neuchatel, Neuchâtel, Switzerland against pollen thieves. 2. Combining an experimental approach with phylogenetic comparative methods, Correspondence Christophe J. Praz and using western Palaearctic Boraginaceae as a model system, we investigate Email: [email protected] how pollen secondary metabolites influence, and are influenced by, relationships Funding information with bees, the main functional group of pollen-foraging pollinators. University of Neuchatel; Foundation 3. We found a significant relationship between the levels of secondary compounds Joachim de Giacomi in the corollas and those in the pollen in the investigated species of Boraginaceae, Handling Editor: Diane Campbell suggesting that baseline levels of pollen secondary compounds may partly be due to spillover from floral tissues. -

Lepidoptera: Gracillariidae) in Turkey

DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.16969/teb.16248 Türk. entomol. bült., 2016, 6(1): 9-14 ISSN 2146-975X Orijinal article (Original araştırma) A new host and natural enemies of Dialectica scalariella (Zeller) (Lepidoptera: Gracillariidae) in Turkey Dialectica scalariella (Zeller) (Lepidoptera: Gracillariidae)’nın yeni konukçu ve doğal düşmanları Cumali ÖZASLAN1* Halil BOLU1 Feza CAN CENGİZ2 Puja RAY3 Summary The study was carried out to determine leaf mining insects species feeding on Echium italicum L. (Boraginaceae) (Italian viper’s bugloss) growing in wheat fields of Edirne and Samsun provinces in 2013. As result of this study, Dialectica scalariella (Zeller, 1850) (Lepidoptera: Gracillariidae) adults were obtained from the samples collected from both provinces. D. scalariella is a first record for insect fauna of Edirne and Samsun provinces. In addition, parasitoids Apanteles sp. (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) and Sympiesis sp. (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) were obtained from D. scalariella larvae collected from E. italicum in Edirne. Key words: Dialectica scalariella, Echium italicum, natural enemies, host plant, Turkey Özet Bu çalışma, Edirne ve Samsun illerinde buğday üretim alanlarında bulunan İtalyan engerek otu (Echium italicum L.) (Boraginaceae) ile beslenen galeri böceklerini belirlemek amacıyla 2013 yılında yürütülmüştür. Çalışma sonucunda Edirne ve Samsun illerinden toplanan örneklerden Dialectica scalariella (Zeller, 1850) (Lepidoptera: Gracillariidae)’nın erginleri elde edilmiştir. D. scalariella Edirne ve Samsun illeri böcek faunası için -

Interpretation Manual of European Union Habitats - EUR27 Is a Scientific Reference Document

INTERPRETATION MANUAL OF EUROPEAN UNION HABITATS EUR 27 July 2007 EUROPEAN COMMISSION DG ENVIRONMENT Nature and biodiversity The Interpretation Manual of European Union Habitats - EUR27 is a scientific reference document. It is based on the version for EUR15, which was adopted by the Habitats Committee on 4. October 1999 and consolidated with the new and amended habitat types for the 10 accession countries as adopted by the Habitats Committee on 14 March 2002 with additional changes for the accession of Bulgaria and Romania as adopted by the Habitats Committee on 13 April 2007 and for marine habitats to follow the descriptions given in “Guidelines for the establishment of the Natura 2000 network in the marine environment. Application of the Habitats and Birds Directives” published in May 2007 by the Commission services. A small amendment to Habitat type 91D0 was adopted by the Habitats Committee in its meeting on 14th October 2003. TABLE OF CONTENTS WHY THIS MANUAL? 3 HISTORICAL REVIEW 3 THE MANUAL 4 THE EUR15 VERSION 5 THE EUR25 VERSION 5 THE EUR27 VERSION 6 EXPLANATORY NOTES 7 COASTAL AND HALOPHYTIC HABITATS 8 OPEN SEA AND TIDAL AREAS 8 SEA CLIFFS AND SHINGLE OR STONY BEACHES 17 ATLANTIC AND CONTINENTAL SALT MARSHES AND SALT MEADOWS 20 MEDITERRANEAN AND THERMO-ATLANTIC SALTMARSHES AND SALT MEADOWS 22 SALT AND GYPSUM INLAND STEPPES 24 BOREAL BALTIC ARCHIPELAGO, COASTAL AND LANDUPHEAVAL AREAS 26 COASTAL SAND DUNES AND INLAND DUNES 29 SEA DUNES OF THE ATLANTIC, NORTH SEA AND BALTIC COASTS 29 SEA DUNES OF THE MEDITERRANEAN COAST 35 INLAND -

Mail Order Catalogue Westcountry Nurseries

Westcountry Nurseries Chelsea Gold Medallists Lupinus Masterpiece mail order catalogue 2018 WESTCOUNTRY LUPINS 9cm pots Please note we will substitute with similar colours of named variety lupins unless directed otherwise or if no alternatives are given by you. CASHMERE BEEFEATER BLACKSMITH BLOSSOM ALL LUPINS ARE £7.50 EACH OR 5 OF OUR CHOICE FOR £35 CREAM - please purchase individually if you want certain varieties Lupins are sent out in 9cm/3” pots. Early orders are dispatched from beginning of March. Lupins are always the first to sell out so don’t delay in placing your order! Cultural notes – On receipt of your lupins, plant out as soon as possible firmly into ground prepared only with bonemeal or calcified seaweed. Do not use farmyard manure as this will rot the crowns. aterW in but do not over water at any time. You must place slug pellets (100% safe ones are now available as Advanced Slug Pellets containing Ferris Iron) or a solution of garlic, tobacco or caffeine etc around the plant in its young stages or your lupin will quickly fall victim to slugs. Lupins grow in full sun (ideal) or semi shade but not under trees or a very wet/dark/chalky place. Plants will give their first flower in their first year in June/July depending on when you plant them out and are always best in their second year. Staking is not necessary! If you are DESERT SUN GLADIATOR KING CANUTE MAGIC LANTERN on chalky or slug infested soil, try growing lupins in pots. Vaseline or WD40 around the pot lip keeps them effectively at bay.