Richard W. Pfaff, the Liturgy in Medieval England: a History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Office of the Dead in Portuguese Medieval Uses

nova série | new series 4/1 (2017), pp. 167-204 ISSN 2183-8410 http://rpm-ns.pt The Office of the Dead in Portuguese Medieval Uses João Pedro d’Alvarenga CESEM Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas Universidade Nova de Lisboa [email protected] Resumo Este artigo procura determinar a procedência dos formulários do Ofício de Defuntos dos principais usos litúrgicos medievais portugueses (Braga, Coimbra, Évora e Santa Cruz de Coimbra) e percorrer as mudanças que neles ocorreram até ao início do período moderno. São consideradas as circunstâncias históricas da restauração das diferentes dioceses depois da reconquista, a origem e o percurso dos seus primeiros prelados, as fontes subsistentes de cada uso litúrgico e as suas características específicas, com referência à literatura especializada entretanto produzida. A exemplo do estudo pioneiro de Knud Ottosen, a metodologia assenta também numa ampla comparação das séries de responsórios e versos das Matinas de Defuntos e outras particularidades textuais e musicais de fontes locais e de fontes ibéricas e francesas seleccionadas. Em apêndice, são fornecidas listas exaustivas das fontes manuscritas e impressas dos usos de Braga, Évora e Santa Cruz, incluindo as respectivas localizações e referências bibliográficas relevantes. Palavras-chave Ofício de Defuntos; Usos litúrgicos portugueses; Filiações litúrgicas; Séries de responsórios e de versos; Portugal no período medieval e início do período moderno. Abstract This article aims to establish the ancestry of the formularies of the Office of the Dead in the main Portuguese medieval liturgical uses (Braga, Coimbra, Évora and Santa Cruz in Coimbra) and track their changes up to the early modern period. -

A Complete Course

A Complete Course Forum Theological Midwest Author: Rev.© Peter V. Armenio Publisher:www.theologicalforum.org Rev. James Socias Copyright MIDWEST THEOLOGICAL FORUM Downers Grove, Illinois iii CONTENTS xiv Abbreviations Used for 43 Sidebar: The Sanhedrin the Books of the Bible 44 St. Paul xiv Abbreviations Used for 44 The Conversion of St. Paul Documents of the Magisterium 46 An Interlude—the Conversion of Cornelius and the Commencement of the Mission xv Foreword by Francis Cardinal George, to the Gentiles Archbishop of Chicago 47 St. Paul, “Apostle of the Gentiles” xvi Introduction 48 Sidebar and Maps: The Travels of St. Paul 50 The Council of Jerusalem (A.D. 49– 50) 1 Background to Church History: 51 Missionary Activities of the Apostles The Roman World 54 Sidebar: Magicians and Imposter Apostles 3 Part I: The Hellenistic Worldview 54 Conclusion 4 Map: Alexander’s Empire 55 Study Guide 5 Part II: The Romans 6 Map: The Roman Empire 59 Chapter 2: The Early Christians 8 Roman Expansion and the Rise of the Empire 62 Part I: Beliefs and Practices: The Spiritual 9 Sidebar: Spartacus, Leader of a Slave Revolt Life of the Early Christians 10 The Roman Empire: The Reign of Augustus 63 Baptism 11 Sidebar: All Roads Lead to Rome 65 Agape and the Eucharist 12 Cultural Impact of the Romans 66 Churches 13 Religion in the Roman Republic and 67 Sidebar: The Catacombs Roman Empire 68 Maps: The Early Growth of Christianity 14 Foreign Cults 70 Holy Days 15 Stoicism 70 Sidebar: Christian Symbols 15 Economic and Social Stratification of 71 The Papacy Roman -

Western Europe After the Fall of Rome

1/17/2012 Effects of Germanic Invasions End of the 5th Century Raiders, • Repeated invasions, constant warfare Traders and – Disruption of trade • Merchants invaded from land and sea— Crusaders: businesses collapse – Downfall of cities Western Europe • Cities abandoned as centers for administration After the Fall of – Population shifts • Nobles and other city-dwellers retreat to rural Rome areas • Population of Western Europe became mostly rural The Rise of Europe 500-1300 The Early Middle Ages • Europe was cut off from the advanced civilizations of Byzantium, the Middle East, China and India. • Between 700 and 1000, Europe was battered by invaders. • New forms of social organization developed amid the fragmentation • Slowly a new civilization would emerge that blended Greco-Roman, Germanic and Christian traditions. akupara.deviantart.com Guiding Questions Decline of Learning 1.How was Christianity a unifying social and • Germanic invaders could not read or write political factor in medieval Europe? – Oral tradition of songs and legends • Literacy dropped among those moved to rural areas 2.What are the characteristics of Roman • Priests and other church officials were among Catholicism? the few who were literate • Greek Knowledge was almost lost – Few people could read Greek works of literature, science, and philosophy 1 1/17/2012 Loss of Common Language A European Empire Evolves • Latin changes as German-speaking • After the Roman Empire, Europe divided into people mix with Romans 7 small kingdoms (some as small as Conn.) • No longer understood from region to • The Christian king Clovis ruled the Franks region (formerly Gual) • By 800s, French, Spanish, and other • When he died in 511, the kingdom covered Roman-based (Romance) languages much of what is now France. -

Increasing Egg Consumption at Breakfast Is Associated With

nutrients Article Increasing Egg Consumption at Breakfast Is Associated with Increased Usual Nutrient Intakes: A Modeling Analysis Using NHANES and the USDA Child and Adult Care Food Program School Breakfast Guidelines Yanni Papanikolaou 1,* and Victor L. Fulgoni III 2 1 Nutritional Strategies, Nutrition Research & Regulatory Affairs, 59 Marriott Place, Paris, ON N3L 0A3, Canada 2 Nutrition Impact, Nutrition Research, 9725 D Drive North, Battle Creek, MI 49014, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-519-504-9252 Abstract: The objective of the current modeling analysis was three-fold: (1) to examine usual nutrient intakes in children when eggs are added into dietary patterns that typically do not contain eggs; (2) to examine usual nutrient intakes with the addition of eggs in the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) school breakfast; and (3) to examine nutrient adequacy when eggs are included in routine breakfast patterns and with the addition of eggs to the CACFP school breakfast program. Dietary recall data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–2016 (children aged 1–18 years-old; n = 9254; CACFP n = 159) were used in the analysis. The usual intakes of pantothenic acid, riboflavin, selenium, and vitamin D increased ≥10 percent (relative to the baseline values) with Citation: Papanikolaou, Y.; Fulgoni, the addition of one egg at breakfast. The usual intakes of protein and vitamin A at breakfast were V.L., III Increasing Egg Consumption also increased by more than 10 percent compared to the baseline values with the addition of two at Breakfast Is Associated with eggs. -

University of Birmingham Algerian Women and the Traumatic

University of Birmingham Algerian Women and the Traumatic Decade: Daoudi, Anissa License: None: All rights reserved Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Daoudi, A 2017, 'Algerian Women and the Traumatic Decade: Literary Interventions', Journal of Literature and Trauma Studies. Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. If you believe that this is the case for this document, please contact [email protected] providing details and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate. -

The Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages After the collapse of Rome, Western Europe entered a period of political, social, and economic decline. From about 500 to 1000, invaders swept across the region, trade declined, towns emptied, and classical learning halted. For those reasons, this period in Europe is sometimes called the “Dark Ages.” However, Greco-Roman, Germanic, and Christian traditions eventually blended, creating the medieval civilization. This period between ancient times and modern times – from about 500 to 1500 – is called the Middle Ages. The Frankish Kingdom The Germanic tribes that conquered parts of the Roman Empire included the Goths, Vandals, Saxons, and Franks. In 486, Clovis, king of the Franks, conquered the former Roman province of Gaul, which later became France. He ruled his land according to Frankish custom, but also preserved much of the Roman legacy by converting to Christianity. In the 600s, Islamic armies swept across North Africa and into Spain, threatening the Frankish kingdom and Christianity. At the battle of Tours in 732, Charles Martel led the Frankish army in a victory over Muslim forces, stopping them from invading France and pushing farther into Europe. This victory marked Spain as the furthest extent of Muslim civilization and strengthened the Frankish kingdom. Charlemagne After Charlemagne died in 814, his heirs battled for control of the In 786, the grandson of Charles Martel became king of the Franks. He briefly united Western empire, finally dividing it into Europe when he built an empire reaching across what is now France, Germany, and part of three regions with the Treaty of Italy. -

Unit 5: the Post-Classical Period: the First Global Civilizations

Unit 5: The Post-Classical Period: The First Global Civilizations Name: ________________________________________ Teacher: _____________________________ IB/AP World History 9 Commack High School Please Note: You are responsible for all information in this packet, supplemental handouts provided in class as well as your homework, class webpage and class discussions. What do we know about Muhammad and early Muslims? How do we know what we know? How is our knowledge limited? Objective: Evaluate the primary sources that historians use to learn about early Muslims. Directions: Below, write down two things you know about Muhammad and how you know these things. What I know about Muhammad... How do I know this …. / Where did this information come from... Directions: Below, write down two things you know about Muslims and how you know these things. What I know about Muslims... How do I know this …. / Where did this information from from... ARAB EXPANSION AND THE ISLAMIC WORLD, A.D. 570-800 1. MAKING THE MAP 1. Locate and label: 4. Locate and label: a Mediterranean Sea a Arabian Peninsula b Atlantic Ocean b Egypt c Black Sea c Persia (Iran) d Arabian Sea d Anatolia e Caspian Sea e Afghanistan f Aral Sea f Baluchistan g Red Sea g Iraq h Persian Gulf. 2. Locate and label: h Syria a Indus River i Spain. b Danube River 5. Locate and label: c Tigris River a Crete b Sicily d Euphrates River c Cyprus e Nile River d Strait of Gibraltar f Loire River. e Bosphorus. 3. Locate and label: 6. Locate with a black dot and a Zagros Mountains label: b Atlas Mountains a Mecca c Pyrenees Mountains b Medina d Caucasus Mountains c Constantinople e Sahara Desert. -

385 Richard W. Pfaff, the Liturgy in Mediaeval England

Book Reviews / Ecclesiology 9 (2013) 367–412 385 Richard W. Pfaff, The Liturgy in Mediaeval England: A History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009) xxviii + 593 pp. £75.00/$120.00. ISBN 978- 0-521-80847-7 (hbk). Richard Pfaff, now Emeritus Professor of History at the University of North Carolina, has spent a professional lifetime working on the liturgy in Mediaeval England. This volume is both a testimony to these labours and an indispensable guide to the texts in this field, that will be the standard map of the territory for many years to come. There is no other comparable resource, and this book is all the more valuable as it gives a summary of the history of the study of some of the primary sources and analyses the value of their nineteenth- or early twentieth-century editions. Pfaff’s particular interests give a slant to some of the material – not least in the choice of what to leave out. His earlier work (notably New Liturgical Feasts in Later Medieval England [1970], Liturgical Calendars, Saints, and Services in Medieval England [1998]) explored means of tracking regional links and dating additions and alterations to the calendar. In this massive survey, ranging from what we know of pre-Augustine liturgy in England – not an enormous amount! – to the lavish printings on the eve of the Reformation, he consciously omits any study of pastoral rites and of the popular devotional literature – the books of hours and personal missals which frequently interest the romantic leanings of social historians and (rightly) excite the art historians – nor does he touch the complex area of pontifical liturgy. -

Chapter 4: China in the Middle Ages

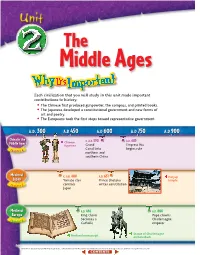

The Middle Ages Each civilization that you will study in this unit made important contributions to history. • The Chinese first produced gunpowder, the compass, and printed books. • The Japanese developed a constitutional government and new forms of art and poetry. • The Europeans took the first steps toward representative government. A..D.. 300300 A..D 450 A..D 600 A..D 750 A..DD 900 China in the c. A.D. 590 A.D.683 Middle Ages Chinese Middle Ages figurines Grand Empress Wu Canal links begins rule Ch 4 apter northern and southern China Medieval c. A.D. 400 A.D.631 Horyuji JapanJapan Yamato clan Prince Shotoku temple Chapter 5 controls writes constitution Japan Medieval A.D. 496 A.D. 800 Europe King Clovis Pope crowns becomes a Charlemagne Ch 6 apter Catholic emperor Statue of Charlemagne Medieval manuscript on horseback 244 (tl)The British Museum/Topham-HIP/The Image Works, (c)Angelo Hornak/CORBIS, (bl)Ronald Sheridan/Ancient Art & Architecture Collection, (br)Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY 0 60E 120E 180E tecture Collection, (bl)Ron tecture Chapter Chapter 6 Chapter 60N 6 4 5 0 1,000 mi. 0 1,000 km Mercator projection EUROPE Caspian Sea ASIA Black Sea e H T g N i an g Hu JAPAN r i Eu s Ind p R Persian u h . s CHINA r R WE a t Gulf . e PACIFIC s ng R ha Jiang . C OCEAN S le i South N Arabian Bay of China Red Sea Bengal Sea Sea EQUATOR 0 Chapter 4 ATLANTIC Chapter 5 OCEAN INDIAN Chapter 6 OCEAN Dahlquist/SuperStock, (br)akg-images (tl)Aldona Sabalis/Photo Researchers, (tc)National Museum of Taipei, (tr)Werner Forman/Art Resource, NY, (c)Ancient Art & Archi NY, Forman/Art Resource, (tr)Werner (tc)National Museum of Taipei, (tl)Aldona Sabalis/Photo Researchers, A..D 1050 A..D 1200 A..D 1350 A..D 1500 c. -

General Instructions Income Tax

GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS INCOME TAX INTRODUCTION must be the same as the Federal. A copy of the Federal return The Georgia law recognizes an election to file as an S Corpo- and all supporting schedules must be attached to the Georgia ration under the provisions of the IRC as it existed on January return. If a Federal audit results in a change in taxable income, 1, 2002, qualified only in cases of nonresident shareholders, the taxpayer shall make a return to the Commissioner of the who must complete Form 600 S-CA (see Page 9). It also pro- changed or corrected net income within 180 days of final deter- vides for the imposition of a Net Worth Tax. mination. The return should be mailed to: Georgia Income Tax Division, P.O. Box 49432, Atlanta, Georgia 30359-1432. FILING REQUIREMENTS COMPUTING GEORGIA TAXABLE INCOME All corporations owning property or doing business within SCHEDULE 1 Georgia are required to file a Georgia income tax return. (Please If an S Corporation is required to pay a tax at the federal level, round all dollar entries.) A corporation electing the provisions of it may be required to pay a tax at the state level. This schedule the IRC for S Corporations, having one or more stockholders applies only to S Corporations which have converted from a C who are nonresidents of Georgia, must file a Form 600 S-CA Corporation and are subject to the corporate income tax due to on behalf of each nonresident. Failure to furnish a properly Excess Net Passive Investment Income, Capital Gains or Built executed Form 600 S-CA for each nonresident stockholder in Capital Gains. -

Dietary Supplement Ingredient Database (DSID): Preliminary USDA Studies on the Composition of Adult Multivitamin/Mineral Supplements$

ARTICLE IN PRESS JOURNAL OF FOOD COMPOSITION AND ANALYSIS Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 21 (2008) S69–S77 www.elsevier.com/locate/jfca Report Dietary supplement ingredient database (DSID): Preliminary USDA studies on the composition of adult multivitamin/mineral supplements$ Janet M. Roselanda,Ã, Joanne M. Holdena, Karen W. Andrewsa, Cuiwei Zhaoa, Amy Schweitzera, James Harnlyb, Wayne R. Wolfb, Charles R. Perryc, Johanna T. Dwyerd, Mary Frances Piccianod, Joseph M. Betzd, Leila G. Saldanhad, Elizabeth A. Yetleyd, Kenneth D. Fisherd, Katherine E. Sharplesse aNutrient Data Laboratory, Beltsville Human Nutrition Research Center, Agricultural Research Service, US Department of Agriculture, Beltsville, MD 20705, USA bFood Composition Laboratory, Beltsville Human Nutrition Research Center, Agricultural Research Service, US Department of Agriculture, Beltsville, MD, USA cResearch and Development Division, National Agricultural Statistics Service, US Department of Agriculture, Fairfax, VA, USA dOffice of Dietary Supplements, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, MD, USA eNational Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, USA Received 19 March 2007; received in revised form 12 June 2007 Abstract The Nutrient Data Laboratory of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is collaborating with the Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS), the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), and other government agencies to design and populate a dietary supplement ingredient database (DSID). This analytically based, publicly available database will provide reliable estimates of vitamin and mineral content of dietary supplement (DS) products. The DSID will initially be populated with multivitamin/mineral (MVM) products because they are the most commonly consumed supplements. Challenges associated with the analysis of MVMs were identified and investigated. -

7.1 Introduction Our Study of Islam Begins with the Arabian Peninsula

Name and Date: _________________________ Text: HISTORY ALIVE! The Medieval World 7.1 Introduction Our study of Islam begins with the Arabian Peninsula, where Islam was first preached. The founder of Islam, Muhammad, was born on the peninsula in about 570 C.E. In this chapter, you’ll learn about the peninsula’s geography and the ways of life of its people in the sixth century. The Arabian Peninsula is in southwest Asia, between the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf. It is often called Arabia. Along with North Africa, the eastern Mediterranean shore, and present day Turkey, Iraq, and Iran, it is part of the modern Middle East. Most of the people living in Arabia in the sixth century were Arabs. Some Arabs call their home al-Jazeera, or “the Island.” But it is surrounded by water on only three sides. The Persian Gulf lies to the east, the Red Sea to the west, and the Indian Ocean to the south. To the north are lands bordering the Mediterranean Sea. These lands serve as a land bridge between Africa, Asia, and Europe. Imagine that you are flying over the Arabian Peninsula. As you look down, you see vast deserts dotted by oases. Coastal plains line the southern and western coasts. Mountain ranges divide these coastal plains from the desert. The hot, dry Arabian Peninsula is a challenging place to live. In this chapter, you will study the geography of Arabia and its different environments. You’ll see how people made adaptations in order to thrive there. 7.2 The Importance of the Arabian Peninsula and Surrounding Lands Arabia lies at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe.