The Journal of Texas Music History Marks History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IS/SONY in High Gear W/Japanese Market on Eve Ur Inch Disks Bow

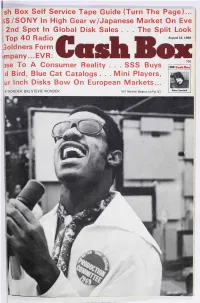

i sh Box Self Service Tape Guide (Turn The Page) ... IS/SONY In High Gear w/Japanese Market On Eve 2nd Spot In Global Disk Sales . The Split Look August 16, 1969 i Top 40 Radio ,;oldners Form ash.,mpany...EVR: )se To A Consumer Reality ... SSS Buys Ott Cash Box754 d Bird, Blue Cat Catalogs ... Mini Players, ur Inch Disks Bow On European Markets... Peter Sarstedt E WONDER: BIG STEVIE WONDER Intl Section Begins on Pg. 61 www.americanradiohistory.com The inevitable single from the group that brought you "Young Girl" and "WomanYVoman:' EC "This Girl Is Dir Ai STA BII aWoman Now7 hbAn. by Gary Puckett COiN and The Union Gap. DEE On Columbia Records* Di 3 II Lodz,' Tel: 11A fie 1%. i avb .» o www.americanradiohistory.com ///1\\ %b\\ ISM///1\\\ ///=1\\\ Min 111 111\ //Il11f\\ 11111111111111 1/11111 III111 MUSIC -RECORD WEEKLY ii INTERNATIONAL milli 1IUUIII MI/I/ MIII II MU/// MUMi M1111/// U1111D U IULI glia \\\1197 VOL. XXXI - Number 3/August 16, 1969 Publication Office / 1780 Broadway, New York, New York 10019 / Telephone JUdson 6-2640 / Cable Address: Cash Box, N. Y. GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher MARTY OSTROW Vice President IRV LICHTMAN Editor in Chief EDITORIAL MARV GOODMAN Cash Box Assoc. Editor JOHN KLEIN BOB COHEN BRUCE HARRIS Self- Service EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS MIKE MARTUCCI ANTHONY LANZETTA Tape Guide ADVERTISING BERNIE BLAKE Director of Advertising ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES STAN SOIFER, New York BILL STUPER, New York HARVEY GELLER, Hollywood Much of the confusion facing first - 8 -TRACK CARTRIDGES: Using the WOODY HARDING unit tape consumers lies in the area same speed and thickness of tape Art Director of purchaser education. -

Z 102 Coltrane, John / Giant Steps Z 443 Cooke, Sam

500 Rank Album 102 Coltrane, John / Giant Steps 285 Green, Al / I'm Still in Love With You 180 Abba / The Definitive Collection 443 Cooke, Sam / Live at the Harlem Square Club 61 Guns N'Roses / Appetite for Destruction 73 AC/DC / Back in Black 106 Cooke, Sam / Portrait of a Legend 484 Haggard, Merle / Branded Man 199 AC/DC / Highway to Hell 460 Cooper, Alice / Love It to Death 437 Harrison, George / All Things Must Pass 176 Aerosmith / Rocks 482 Costello, Elvis / Armed Forces 405 Harvey, PJ / Rid of Me 228 Aerosmith / Toys in the Attic 166 Costello, Elvis / Imperial Bedroom 435 Harvey, PJ / To Bring You My Love 49 Allman Brothers Band / At Fillmore East 168 Costello, Elvis / My Aim Is True 15 Hendrix, Jimi Experience / Are You Experienced? 152 B-52's / The B-52's 98 Costello, Elvis / This Year's Model 82 Hendrix, Jimi Experience / Axis: Bold as Love 34 Band / Music from Big Pink 112 Cream / Disraeli Gears 54 Hendrix, Jimi Experience / Electric Ladyland 45 Band / The Band 101 Cream / Fresh Cream 389 Henley, Don / The End of the Innocence 2 Beach Boys / Pet Sounds 203 Cream / Wheels of Fire 312 Hill, Lauryn / The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill 380 Beach Boys / Sunflower 265 Creedence Clearwater Revival / Cosmo's Factory 466 Hole / Live Through This 270 Beach Boys / The Beach Boys Today! 95 Creedence Clearwater Revival / Green River 421 Holly, Buddy & the Crickets / The Chirpin' Crickets 217 Beastie Boys / Licensed to Ill 392 Creedence Clearwater Revival / Willy and the Poor Boys 92 Holly, Buddy / 20 -

MCA-700 Midline/Reissue Series

MCA 700 Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan MCA-700 Midline/Reissue Series: By the time the reissue series reached MCA-700, most of the ABC reissues had been accomplished in the MCA 500-600s. MCA decided that when full price albums were converted to midline prices, the albums needed a new number altogether rather than just making the administrative change. In this series, we get reissues of many MCA albums that were only one to three years old, as well as a lot of Decca reissues. Rather than pay the price for new covers and labels, most of these were just stamped with the new numbers in gold ink on the front covers, with the same jackets and labels with the old catalog numbers. MCA 700 - We All Have a Star - Wilton Felder [1981] Reissue of ABC AA 1009. We All Have A Star/I Know Who I Am/Why Believe/The Cycles Of Time//Let's Dance Together/My Name Is Love/You And Me And Ecstasy/Ride On MCA 701 - Original Voice Tracks from His Greatest Movies - W.C. Fields [1981] Reissue of MCA 2073. The Philosophy Of W.C. Fields/The "Sound" Of W.C. Fields/The Rascality Of W.C. Fields/The Chicanery Of W.C. Fields//W.C. Fields - The Braggart And Teller Of Tall Tales/The Spirit Of W.C. Fields/W.C. Fields - A Man Against Children, Motherhood, Fatherhood And Brotherhood/W.C. Fields - Creator Of Weird Names MCA 702 - Conway - Conway Twitty [1981] Reissue of MCA 3063. -

Q Casino Announces Four Shows from This Summer's Back Waters

Contact: Abby Ferguson | Marketing Manager 563-585-3002 | [email protected] February 28, 2018 - For Immediate Release Q Casino Announces Four Shows From This Summer’s Back Waters Stage Concert Lineup! Dubuque, IA - The Back Waters Stage, Presented by American Trust, returns this summer on Schmitt Island! Q Casino is proud to announce the return of our outdoor summer experience, Back Waters Stage. This summer, both national acts and local favorites will take the stage through community events and Q Casino hosted concerts. All ages are welcome to experience the excitement at this outdoor venue. Community members can expect to enjoy a wide range of concerts from all genres from modern country to rock. The Back Waters Stage will be sponsoring two great community festivals this summer. Kickoff to Summer will be kicking off the summer series with a free show on Friday, May 25. Summer’s Last Blast 19 which is celebrating 19 years of raising money for area charities including FFA, the Boy Scouts, Dubuque County Fairgrounds and Sertoma. Summer’s Last Blast features the area’s best entertainment with free admission on Friday, August 24 and Saturday, August 25. The Back Waters Stage Summer Concert Series starts off with country rappers Colt Ford and Moonshine Bandits on Saturday, June 16. Colt Ford made an appearance in the Q Showroom last March to a sold out crowd. Ford has charted six times on the Hot Country Songs charts and co-wrote “Dirt Road Anthem,” a song later covered by Jason Aldean. On Thursday, August 9, the Back Waters Stage switches gears to modern rock with platinum recording artist, Seether. -

Neglected Jazz Figures of the 1950S and Early 1960S New World NW 275

Introspection: Neglected Jazz Figures of the 1950s and early 1960s New World NW 275 In the contemporary world of platinum albums and music stations that have adopted limited programming (such as choosing from the Top Forty), even the most acclaimed jazz geniuses—the Armstrongs, Ellingtons, and Parkers—are neglected in terms of the amount of their music that gets heard. Acknowledgment by critics and historians works against neglect, of course, but is no guarantee that a musician will be heard either, just as a few records issued under someone’s name are not truly synonymous with attention. In this album we are concerned with musicians who have found it difficult—occasionally impossible—to record and publicly perform their own music. These six men, who by no means exhaust the legion of the neglected, are linked by the individuality and high quality of their conceptions, as well as by the tenaciousness of their struggle to maintain those conceptions in a world that at best has remained indifferent. Such perseverance in a hostile environment suggests the familiar melodramatic narrative of the suffering artist, and indeed these men have endured a disproportionate share of misfortunes and horrors. That four of the six are now dead indicates the severity of the struggle; the enduring strength of their music, however, is proof that none of these artists was ultimately defeated. Selecting the fifties and sixties as the focus for our investigation is hardly mandatory, for we might look back to earlier years and consider such players as Joe Smith (1902-1937), the supremely lyrical trumpeter who contributed so much to the music of Bessie Smith and Fletcher Henderson; or Dick Wilson (1911-1941), the promising tenor saxophonist featured with Andy Kirk’s Clouds of Joy; or Frankie Newton (1906-1954), whose unique muted-trumpet sound was overlooked during the swing era and whose leftist politics contributed to further neglect. -

Austinmusicawards2017.Pdf

Jo Carol Pierce, 1993 Paul Ray, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and PHOTOS BY MARTHA GRENON MARTHA BY PHOTOS Joe Ely, 1990 Daniel Johnston, Living in a Dream 1990 35 YEARS OF THE AUSTIN MUSIC AWARDS BY DOUG FREEMAN n retrospect, confrontation seemed almost a genre taking up the gauntlet after Nelson’s clashing,” admits Moser with a mixture of The Big Boys broil through trademark inevitable. Everyone saw it coming, but no outlaw country of the Seventies. Then Stevie pride and regret at the booking and subse- confrontational catharsis, Biscuit spitting one recalls exactly what set it off. Ray Vaughan called just prior to the date to quent melee. “What I remember of the night is beer onto the crowd during “Movies” and rip- I Blame the Big Boys, whose scathing punk ask if his band could play a surprise set. The that tensions started brewing from the outset ping open a bag of trash to sling around for a classed-up Austin Music Awards show booking, like the entire evening, transpired so between the staff of the Opera House, which the stage as the mosh pit gains momentum audience visited the genre’s desired effect on casually that Moser had almost forgotten until was largely made up of older hippies of a Willie during “TV.” the era. Blame the security at the Austin Stevie Ray and Jimmie Vaughan walked in Nelson persuasion who didn’t take very kindly About 10 minutes in, as the quartet sears into Opera House, bikers and ex-Navy SEALs from with Double Trouble and to the Big Boys, and the Big “Complete Control,” security charges from the Willie Nelson’s road crew, who typical of the proceeded to unleash a dev- ANY HISTORY OF Boys themselves, who were stage wings at the first stage divers. -

Gerry Mulligan Discography

GERRY MULLIGAN DISCOGRAPHY GERRY MULLIGAN RECORDINGS, CONCERTS AND WHEREABOUTS by Gérard Dugelay, France and Kenneth Hallqvist, Sweden January 2011 Gerry Mulligan DISCOGRAPHY - Recordings, Concerts and Whereabouts by Gérard Dugelay & Kenneth Hallqvist - page No. 1 PREFACE BY GERARD DUGELAY I fell in love when I was younger I was a young jazz fan, when I discovered the music of Gerry Mulligan through a birthday gift from my father. This album was “Gerry Mulligan & Astor Piazzolla”. But it was through “Song for Strayhorn” (Carnegie Hall concert CTI album) I fell in love with the music of Gerry Mulligan. My impressions were: “How great this man is to be able to compose so nicely!, to improvise so marvellously! and to give us such feelings!” Step by step my interest for the music increased I bought regularly his albums and I became crazy from the Concert Jazz Band LPs. Then I appreciated the pianoless Quartets with Bob Brookmeyer (The Pleyel Concerts, which are easily available in France) and with Chet Baker. Just married with Danielle, I spent some days of our honey moon at Antwerp (Belgium) and I had the chance to see the Gerry Mulligan Orchestra in concert. After the concert my wife said: “During some songs I had lost you, you were with the music of Gerry Mulligan!!!” During these 30 years of travel in the music of Jeru, I bought many bootleg albums. One was very important, because it gave me a new direction in my passion: the discographical part. This was the album “Gerry Mulligan – Vol. 2, Live in Stockholm, May 1957”. -

Sir Douglas Quintet

Sir Douglas Quintet The Sir Douglas Quintet: Emerging from San Antonio‟s “West Side Sound,” The Sir Douglas Quintet blended rhythm and blues, country, rock, pop, and conjunto to create a unique musical concoction that gained international popularity in the 1960s and 1970s. From 1964 to 1972, the band recorded five albums in California and Texas, and, although its founder, Doug Sahm, released two additional albums under the same group name in the 1980s and 1990s, the Quintet never enjoyed the same domestic success as it had during the late 1960s. A big part of the Sir Douglas Quintet‟s distinctive sound derived from the unique musical environment in which its members were raised in San Antonio. During the 1950s and 1960s, the “moderate racial climate” and ethnically diverse culture of San Antonio—caused in part by the several desegregated military bases and the large Mexican-American population there—allowed for an eclectic cross- pollination of musical styles that reached across racial and class lines. As a result, Sahm and his musical friends helped create what came to be known as the “West Side Sound,” a dynamic blending of blues, rock, pop, country, conjunto, polka, R&B, and other regional and ethnic musical styles into a truly unique musical amalgamation. San Antonio-based artists, such as Augie Meyers, Doug Sahm, Flaco Jiménez, and Sunny Ozuna, would help to propel this sound onto the international stage. Born November 6, 1941, Douglas Wayne Sahm grew up on the predominately-black east side of San Antonio. As a child, he became proficient on a number of musical instruments and even turned down a spot on the Grand Ole Opry (while still in junior high school) in order to finish his education. -

PIVAŘI a FRAJEŘI Průvodce Světem ZZ Top Neil Daniels Beer Drinkers & Hell Raisers: a ZZ Top Guide

Neil Daniels PIVAŘI A FRAJEŘI Průvodce světem ZZ Top Neil Daniels Beer Drinkers & Hell Raisers: A ZZ Top Guide Přeložil Milan Stejskal Translation © Milan Stejskal, 2015 Copyright © Neil Daniels, 2014 ISBN 978-80-7511-121-0 ISBN 978-80-7511-122-7 (epub) ISBN 978-80-7511-123-4 (pdf) Neil Daniels PIVAŘI A FRAJEŘI Průvodce světem ZZ Top PŘEDMLU VA od Stevena Rosena S Billym Gibbonsem a jeho kapelou ZZ Top jsem se poprvé se- známil v roce 1973. Právě vydali album Tres Hombres a já s nimi dělal rozhovor – se všemi třemi – pro nezávislý plátek jménem Los Angeles Free Press. Jakmile jsem vešel do jejich pokoje v ho- telu Continental Hyatt House – nechvalně to proslulém příbyt- ku mnoha rockových hvězd sedmdesátých let, který byl bohužel před mnoha lety zbourán – byl jsem přijat s pravou jižanskou po- hostinností, takže jsem se hned cítil v pohodě a klidu. Billy patřil mezi nejmilejší, nejzábavnější a nejbystřejší lidi, na něž jsem kdy narazil, a také díky tomu jsem si ho od první chvíle zamiloval. Během následujících let jsme se ještě mnohokrát sešli a v této před- mluvě uvedu rozhovor, který se odehrál zhruba šest let po našem prvním setkání. Podle mě právě toto vyprávění nejlépe ilustru- je, jaká kapela byla a je a jací jsou její členové po lidské stránce. Asi vám nemusím říkat, jak důležitou roli ZZ Top sehráli v šíření blues mezi širší vrstvy posluchačů. Billy Gibbons patřil a stále pa- tří mezi nejunikátnější a nejtvořivější kytaristy, kteří kdy drželi šestistrunku v ruce. O tom již napsali mnozí jiní. Ne, já vám nechci vyprávět o Billy Gibbonsovi, Franku Beardovi a Dusty Hillovi z hlediska historie, zvolím spíše osobní pohled. -

Chicago Blues Guitar

McKinley Morganfield (April 4, 1913 – April 30, 1983), known as Muddy WatersWaters, was an American blues musician, generally considered the Father of modern Chicago blues. Blues musicians Big Bill Morganfield and Larry "Mud Morganfield" Williams are his sons. A major inspiration for the British blues explosion in the 1960s, Muddy was ranked #17 in Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time. Although in his later years Muddy usually said that he was born in Rolling Fork, Mississippi in 1915, he was actually born at Jug's Corner in neighboring Issaquena County, Mississippi in 1913. Recent research has uncovered documentation showing that in the 1930s and 1940s he reported his birth year as 1913 on both his marriage license and musicians' union card. A 1955 interview in the Chicago Defender is the earliest claim of 1915 as his year of birth, which he continued to use in interviews from that point onward. The 1920 census lists him as five years old as of March 6, 1920, suggesting that his birth year may have been 1914. The Social Security Death Index, relying on the Social Security card application submitted after his move to Chicago in the mid '40s, lists him as being born April 4, 1915. His grandmother Della Grant raised him after his mother died shortly after his birth. His fondness for playing in mud earned him the nickname "Muddy" at an early age. He then changed it to "Muddy Water" and finally "Muddy Waters". He started out on harmonica but by age seventeen he was playing the guitar at parties emulating two blues artists who were extremely popular in the south, Son House and Robert Johnson. -

Bright Moments!

Volume 46 • Issue 6 JUNE 2018 Journal of the New Jersey Jazz Society Dedicated to the performance, promotion and preservation of jazz. On stage at NJPAC performing Rahsaan Roland Kirk’s “Bright Moments” to close the tribute to Dorthaan Kirk on April 28 are (from left) Steve Turre, Mark Gross, musical director Don Braden, Antoinette Montague and Freddy Cole. Photo by Tony Graves. SNEAKING INTO SAN DIEGO BRIGHT MOMENTS! Pianist Donald Vega’s long, sometimes “Dorthaan At 80” Celebrating Newark’s “First harrowing journey from war-torn Nicaragua Lady of Jazz” Dorthaan Kirk with a star-filled gala to a spot in Ron Carter’s Quintet. Schaen concert and tribute at the New Jersey Performing Arts Fox’s interview begins on page 14. Center. Story and Tony Graves’s photos on page 24. New JerseyJazzSociety in this issue: New Jersey Jazz socIety Prez Sez . 2 Bulletin Board . 2 NJJS Calendar . 3 Jazz Trivia . 4 Prez sez Editor’s Pick/Deadlines/NJJS Info . 6 Change of Address/Support NJJS/ By Cydney Halpin President, NJJS Volunteer/Join NJJs . 43 Crow’s Nest . 44 t is with great delight that I announce Don commitment to jazz, and for keeping the music New/Renewed Members . 45 IBraden has joined the NJJS Board of Directors playing. (Information: www.arborsrecords.com) in an advisory capacity. As well as being a jazz storIes n The April Social at Shanghai Jazz showcased musician of the highest caliber on saxophone and Dorthaan at 80 . cover three generations of musicians, jazz guitar Big Band in the Sky . 8 flute, Don is an award-winning recording artist, virtuosi Gene Bertoncini and Roni Ben-Hur and Memories of Bob Dorough . -

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M.